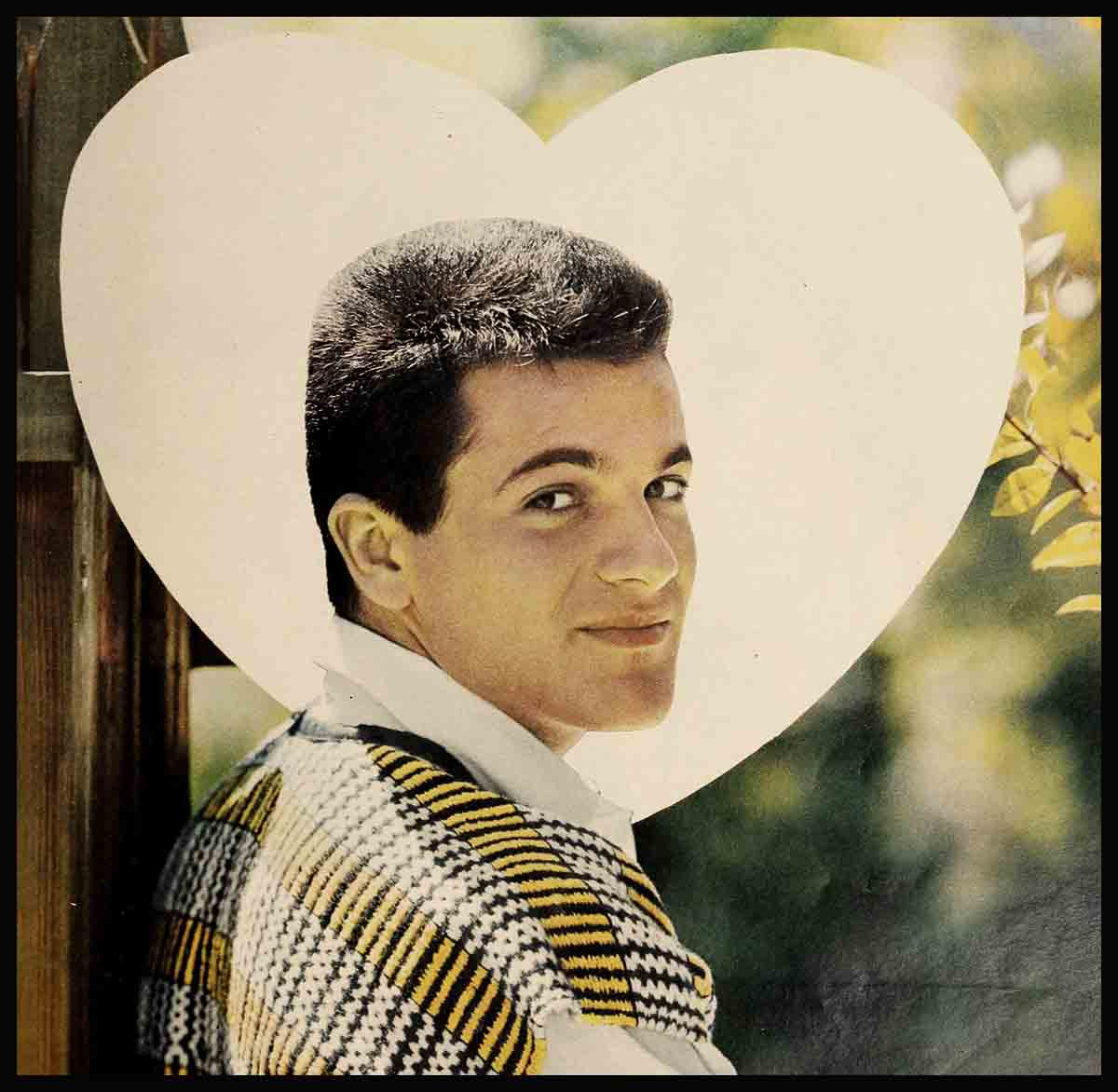

Will You Be My Valentine?—Tommy Sands

Here I am, of age—and all alone.

“What happened?” I keep asking myself. I’ve goofed somewhere along the line. When I was thirteen or fourteen I used to brag about all I knew about girls. I knew the ropes—inside and out. I had this silly dreamworld image, a kind of sugarplum impression. Girls were all sweetness and light, fresh and dewy like the first flowers of spring.

But now that I’m twenty-one, would you believe it I know less about girls than ever? What’s made me this way? Well, I’ll tell you the whole story from start to finish. This is it. The story of the Valentines I have known.

My first Valentine—maybe “crush” is a better word—was Liz Taylor. I first saw her in National Velvet and my head started spinning. I was nine or ten years old, and she made such an impact on me I wrote her a fan letter every week. She sent me a big beautiful glossy picture of herself (I still have it) with a personal autograph: For Tommy, Fondly, Elizabeth Taylor. And I went right out and bought a silver frame for it from our Greenwood, Louisiana, dime store. I kept her framed photograph on the ivory mantelpiece in our living room back home, and I remember, after school, I’d go home for a snack, take a long look at her dark hair, her rosepetal complexion and those innocent blue-violet eyes, and I’d go dizzy.

My mom used to say, “Why don’t you take the picture upstairs to your room?”

But I’d tell her, “No. I like it here. The living room’s the nicest room in our house, and this is where she belongs—with the best!”

Next, I fell in love—crazy kiddish puppy love—with a teacher I had in the fifth grade at Greenwood Grammar, the white wooden country schoolhouse near where I lived. No, the teacher didn’t give me all A’s. Nor was she as beautiful as Liz. She was short, darkhaired, and with a dimple in her left cheek when she smiled. But she was understanding. She gave me confidence. This was when I realized how important girls—or women—are to fellows, how they help us. Lots of mornings my teacher’d ask me to have lunch with her, and she’d give me one of her peanut-butter-and-jelly sandwiches, and wed talk about my ambitions and what I wanted to be when I grew up. I already owned a guitar then. My mother gave me one for my birthday when I was nine years old. I used to tell my teacher during lunchtime how much I loved singing. And she’d constantly remind me how important it was to practice in order to be a professional.

She gave me courage

I’ll never forget one winter’s day when she came to me after school and said, “Tommy, I’ve got a surprise for you.”

She told me she’d arranged for me to sing at the Christmas school assembly. I know I should have shouted with happiness. But I didn’t. I was seared. Oh, I had sung a couple of times on the radio, but when you sing into a microphone in a studio room it’s different. There aren’t very many people around—just a few technicians, that’s all. But singing in front of a big school audience—? Don’t get me wrong. I wanted to sing at the assembly. It’s just that I was afraid I wouldn’t be good.

She helped me plan the program of what I should sing. And every day after school she listened to me practicing. She’d give me suggestions, ideas about the way I should sing the songs. When Christmas week came and the day of the big assembly arrived, butterflies were playing tag in my stomach and I wanted to back out at the last minute. But she said, “Tommy, you’ll never be a singer if you don’t learn to control your stage fright now.”

Finally, when the hour of the assembly came and I waited backstage while all the kids marched into the auditorium, I began to get excited. When the principal of the school announced me and I walked on stage with my guitar and began singing, somehow I forgot everything—the awful stage fright and fluttery butterflies.

I sang a couple of Christmas carols and some folk songs, and when I finished there was dead silence in the school auditorium. I went limp. I started to walk offstage, and then, suddenly, out of the silence, a roar of applause began thundering, breaking the stillness. The kids clapped and clapped, yelling “More, more!” This was the first time in my life I’d ever taken a public bow. I didn’t know what I should do, so I ran offstage, happy but bewildered and almost on the verge of tears.

A guy never forgets

But there she was, my teacher, waiting in the grey-curtained wings. I reached out and hugged her. I couldn’t help it. Without her I would never have done it. She boosted my spirits. She had an interest in seeing me develop. She believed in me—and a guy never forgets this.

For the rest of that school year I hung around her like a puppy dog. On the last day of school when we had parties in all the classrooms, I kissed her on the cheek and I cried. We were moving to Chicago. I told her the news and she smiled and told me the biggest lesson all of us had to learn was to get along by ourselves in this world wherever we went. We need people to help us, yes, but whether I was in Chicago or Greenwood didn’t matter. What mattered, she said, was that Tommy Sands believed in Tommy Sands enough to stand up for Tommy Sands. Ive never forgotten what she told me. This is why I’ve been able to travel so much, to make hundreds of personal appearances with disc jockeys every year and still stay in a good humor. I always remember her words.

Then the real love trouble started. Until that time, love was a spiral of spun-glass, reflecting the gold of the sun and the silver of the moon. Well, we moved to Chicago, then to the oilman’s world of Houston, Texas, where my mother got a job as a salesclerk in Foley’s Department Store. I started junior high and flipped for the daughter of an oil millionaire.

She was pretty. She was a blonde with deep blue eyes, the kind that seem to look right through you. I don’t know why she liked me. I was poor and hung around with the rough guys, the fellows who loafed in the poolroom parlors where we smoked cigarettes or played cards or just stood outside the pool hall, checking all the gals who’d pass by.

I liked her because she was different. Her first initial is S. I’m embarrassed to give you her real name—it wouldn’t be fair to her; so let’s call her Sandy. Sandy flirted with me at school. But even though I hung around with the rough guys, I was shy. I didn’t have the nerve to go up to her and introduce myself. So I asked a buddy of mine, a halfback on the school’s football team, to fix me up with a date.

Funny thing is he told me she asked him the same thing.

She made up my mind

We met, and I took Sandy out for Cokes, and we sat in the drug store twisting soda straws and talking about silly things like the biggest bubbles we ever blew with bubble gum. She told me her father bought her a brand new record player, a fancy hi-fi set, for her birthday, and why didn’t I come over some night to listen to it?

One October night I went over to her house. It was a huge mansion with a wide driveway and a rolling lawn littered with rustling yellow leaves. I was almost ashamed to go in. I didn’t think I belonged there. This was a rich world, a world I only knew from movies and books. I met her folks who were very formal, but Sandy asked me into the den and we listened to pop records and made milkshakes in the ice cream bar. Later, we danced, with the lamp light turned low to Smoke Gets In Your Eyes.

She told me she had made up her mind to be my girl.

I was bowled over. I had never asked her. “But gee,” I said, “why don’t we go together for a while and see if we like each other? You don’t know me very well, and maybe you won’t like me.” I didn’t tell her then I was afraid she was too rich. After all, I couldn’t afford to take her out very often. My mother had to work, and I used to do odd jobs to pick up an extra buck for spending money.

“No,” she said. “I think we ought to make an agreement right now. We know we like each other, so let’s say we’re going steady right off.”

I was flattered. After all, she was very pretty. She looked a little bit like Sandra Dee, all creamy-complexioned and blue-eyed.

“Okay,” I said, and she gave me her lips in the shadows, and we kissed. I had never had a girl kiss me like that before. I’d kissed gals on the cheek, and once at someone’s birthday party in Chicago where we played post office we kissed on the lips—but those were quick kisses. This was a long, lingering kiss, and I wondered if maybe I wasn’t up to her. She was fast. I was naive. And to tell you the truth, I didn’t know if this was right.

We went together for a month, and we were both miserable. Have you ever heard of possessive people? Well, this is what we both turned out to be. We weren’t sure of ourselves, I guess. If I wanted to play basketball with my pals, she wanted me to go home with her and dance. If she wanted to go for a ride with a gang-of schoolkids, I wanted to go to a Debbie Reynolds movie. We were always fighting, never agreeing on what we might do together.

Too fast for me

One Friday night that November she told me she wanted me to stay over at her house. Her parents were going away for the week end, and she didn’t want to be alone.

“But what will I tell my mother?” I asked her.

“Tell her you’re going to stay over with your best buddy.”

I’ve never liked lying to my mom, but Sandy convinced me I couldn’t leave her by herself in that rambling millionaire’s mansion. That night we made grilled American cheese sandwiches and listened to records and danced. Finally, around ten o’clock, I got a glass of milk from the kitchen, and I told her I was nervous—that this wasn’t right, the two of us staying alone in this big house—and I made her call her girlfriend, Sue, who came over and stayed with Sandy, and I went home to my Mom and told her I had decided against staying over at Bill’s.

The next morning Sandy called me up on the telephone and said she had to see me immediately. I met her at her home, and she gave me my identification bracelet back and said we were through. She didn’t like me anymore. I didn’t have any guts, she told me. This upset me for a long time, and I didn’t date girls for a while. I was afraid of getting mixed-up with someone like Sandy. Sandy didn’t want to go steady. It was more like husband wife with her. Going steady, in my book, means getting to know someone. If you make up your mind to marry, then that’s something altogether different.

It wasn’t until my senior year at Lamar High School when my best buddy’s girlfriend wanted me to doubledate with them that I got hooked. A new girl came to town from Corpus Christi. Her name was Joie, and she had long coalblack hair and green eyes.

On our first date we went to a drive-in and saw a Jimmy Dean film. Joie was warm and easy to get along with. She had a wonderful way of throwing her head back when she laughed. Also, she made a guy feel like a guy with such simple little things. She’d wait for me to open the car door for her. Or she’d ask me to help her off with her coat.

A wonderful girl this time

After the movie, we went to a jukebox joint where there was a parrot in a cage that kept saying “Rock it . . . rock it . . . rock it” or “Hey, when’s the next cha-cha-cha . . .?” Everytime Joie heard the parrot talk she laughed and laughed. I enjoyed her. She had such a love for the little things around her. She wanted to know about all of us at school, the places the seniors liked to go to, the school hops and the holiday proms and the senior dances. I liked her curiosity. I hoped she liked me.

She did. We began going together. In those days I was singing at night, whenever I could get a job. I’d sing in tawdry, rose-lighted beer halls or noisy, smoke-filled gambling casinos. Lots of times Joie would ask me if she could come and catch my show.

I’d say, “No, baby, these places are terrible. I have to sing there because of the dough, but I hate for you to have to go there.”

Somehow or other, in spite of my begging, she’d find some excuse as to why she had to see me and come—alone or with her girlfriends. I was afraid her folks would find out and get upset. Her father was a physician. I didn’t think he’d go for Joie hanging around nightclubs with me. Now I didn’t sing every night—only once or twice a week, and we usually dated on my off nights. I couldn’t understand why she wanted to come to these cheap dives. I kept asking her not to come, but she never listened. She always came.

It didn’t take long for the secret to come out. One spring morning in wood-shop class, my best buddy let the cat out of the bag. The two of us were over by the buzz saw, working on our foot-stool projects, and he said, above the droning noise of the saw, “Hey, Tommy, I hear you got a great arrangement of Love Me or Leave Me! Joie says it’s terrific!”

I was baffled but I didn’t say anything. I had only sung that arrangement the night before for the first time. How did he know about it so quickly?

“She’s so proud of you,” he told me, guiding his piece of pine wood toward the buzz saw’s teeth. “She’s been telling us all she’s been following you around the clubs. She’s devoted to you, you know. She likes going with a singer.”

“Yeah,” I said softly, but he couldn’t hear me. Suddenly my brain clicked. Joie would always come to hear me sing at the clubs, stay for about forty-five minutes, then leave for home early in her fire-engine-red convertible.

“Say,” I said casually, “when did she tell you about my new arrangement?”

“Last week sometime, I guess,” he said, not lifting up his eyes and pushing his square of wood toward the thin blade.

“You’re lying,” I said to him. I reached for the buzz saw switch and snapped off the motor.

“No, I’m not,” he said. “. . . I’m not!”

“Well, I’m going to call your bluff” I told him I wanted him to meet me at noontime at the hot-dog bar across the street. When I saw Joie between classes that morning I told her I wanted to see her, too. I didn’t tell her why.

Betrayed!

Then, when the two of them met me there, I saw him blush when she came in the door.

I explained to Joie I couldn’t understand how word had leaked out about my arrangement of Love Me Or Leave Me. I had only sung it last night, not last week, and she was the only person who had heard it. When did she tell him?

The two of them looked at each other. Finally Joie spoke, her cheeks red from embarrassment. She said, “I think we ought to tell Tommy the truth.” Then she told me they had fallen in love. She liked my singing and coming to hear me sing, but she couldn’t help it. There was something that attracted her to him, and she used to meet him after she saw me at the clubs.

“I guess that explains why you’ve been so busy on my off nights when I’d ask you for a date. You’ve got homework or your hair to wash or something . . . it’s always something.”

“I’m sorry,” she said, lowering her eyes, then looking up at him. No doubt about it, my best buddy was a good-looking guy. He looked a little like Johnny Saxon.

“I hope you won’t be mad at us about it,” she said, “but we just couldn’t help it.”

Suddenly I just couldn’t say anything. I think I’d have made a fool of myself if I stayed there. Tears were building up inside me. I liked Joie, and I liked the way the two of us had been getting to know each other—slowly, gently. But things don’t always go quite the way you’d like them to. I clenched my fists and walked out of that hot-dog bar, the sizzle of the hot dogs on the counter grill sounding like the sizzle in my brain from all this I left and walked home, trying desperately to hold back the tears. I didn’t want anyone to see me. When I got home I went upstairs and locked myself in my room and cried. For the rest of the afternoon I played hookey. I just couldn’t go to school and face them. I had been betrayed by my steady girlfriend and my best buddy.

When my mother came home from Foley’s department store, she knocked on my door. I opened it. She wanted to know what was the matter.

I told her about Joie.

“Son,” she said, “listen to me. It’s better now than later, before you got too serious. There are other girls in the world.”

But I was serious. Anyhow, mothers sometimes can’t understand the immediate pain, that awful, personal anguish of teenage heartbreak, and all I could say to her was “Mom, I think I want to be alone. . . .” She was wonderful. She didn’t pester me. She brought me a tray of things to eat, then left me to my troubles.

The next day I went to school and bumped into my buddy in the coat room, and I said, “I’m not going to do this to you because you took Joie away from me, but I’m going to do this because you were my best friend and you betrayed me!” and I socked him. I couldn’t help it. I had to. There was too much tension inside.

“All right,” I yelled. “Fight me.”

But he didn’t. He said, “You’re right. I was wrong. I’ve been a coward, I can’t help it. I love her. . . .”

A new heart throb

I carried the torch for Joie up till I acted in The Singing Idol on television. Two months later, I met Molly Bee, the gal with the daydream in her eyes. She was a big star, and I looked up to her.

When we appeared on Tennessee Ernie’s program together in California, she invited me to her house. I flipped. She had all kinds of guys at her beck and call—guys who were calling her up at all hours of the day and night to take her on rides, picnics, parties. Why did she ask me?

Well, she told me she loved the way I sang, and before you knew it that old love clutch started pulling at my heart, and suddenly, there we were, seeing each other regularly. We didn’t go steady, but we might as well have.

She used to go out with other fellows, but I couldn’t go out with other girls. I felt I’d be untrue. So I’d say home and wonder, “Who’s Molly out with tonight? What’s Molly doing?” And before you know it, this kind of stuff, night after night, eats away at your heart and cracks it. So I said to myself, “Tommy, it’s time you grew up. You’re going to be twenty-one. Be a man. If this is the way Molly wants it, then Molly’s not for you!” Don’t misunderstand me now. We did have a lot of wonderful times together. But I wanted to be serious about our romance, I didn’t want it to be a flip boy-meets-girl, boy-forgets-girl kind of thing. Molly meant something to me. She was a person with ‘heart,’ if you know what I mean.

When I decided the time came for me to try to be a man, I began dating. A girl with a peppy personality takes a guy’s mind away from himself.

But, so far, no Valentine. Now I say to myself when a guy reaches twenty-one and he doesn’t have a girlfriend, then something’s missing from his life. At least I know that much about love.

So, as I said at the start, here I am, twenty-one year old beau. Available.

With Valentine’s Day around the corner, is anybody else in a dating mood?

THE END

Editor’s note: Tommy will personally write a letter to the girl whose picture he thinks—comes closest to his ideal sweetheart—the girl he’s searched for all his life. Just address your letter to Tommy Sands in care of Modern Screen, 750 Third Avenue, New York 17, New York.

Tommy is appearing in MARDI GRAS for 20th-Fox.

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE MARCH 1959