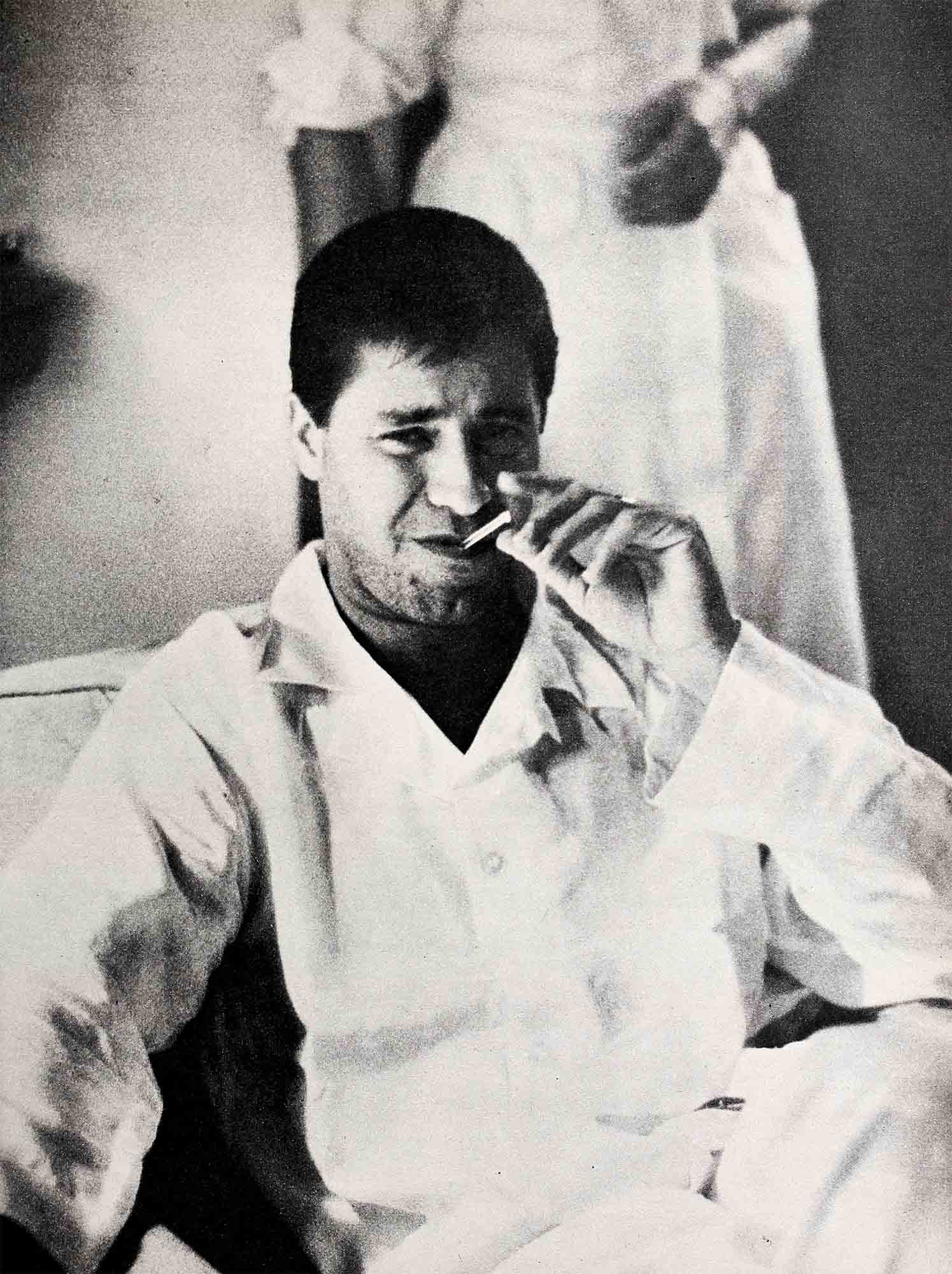

Jerry Lewis In Hospital

“Jerry Lewis In Hospital” . . . “Heart Attack For Comic” . . . These were the newspaper stories. The rumors were even more dire. You were worried and wrote us. Now, here is the truth, as we uncovered it, on what really happened during Jerry Lewis’ ten days in the hospital.—THE EDITORS

On October 30, 1958, at 3:32 in the morning, Jerry Lewis sat bolt upright in bed and screamed.

His wife Patti snapped on the lamp on the night-table and saw her husband clutching his stomach. All color had drained out of his face and he was gasping for breath.

“Patti, Patti,” he mumbled, “Patti, the pain . . . the pain . . . it’s awful.” And then he slumped back on his pillow.

AUDIO BOOK

Not knowing what to do, Patti went for a glass of water and sprayed it in Jerry’s face and then clumsily sopped up the water with a towel. She ran to the telephone and dialed the number of their personal physician, Dr. Marvin S. Levy. After talking to the doctor, she returned to Jerry and, sounding as confident as she could, said, “Help is coming, honey. Everything will be all right.”

Jerry winked at her and then stuck out his tongue. She forced a smile. Seeming satisfied, he closed his eyes again. Patti forced herself to close her own eyes, too, and resting her head on the pillow next to him, she prayed.

Twenty minutes later the ambulance arrived, awakening their sons, 13-year-old Gary and 9-year-old Ronnie, who came sleepily down the hall to find out what was happening. Explaining what had taken place, Patti told them to go into the younger boys’ room—Scotty, three, and Chris, one—to reassure the younger boys if the ambulance’s siren had awakened them, too. Then she went downstairs to open the door for Dr. Levy and the ambulance attendants.

The doctor hurried upstairs and into Jerry’s bedroom. He felt Jerry’s pulse and then gently opened his eyes. Jerry rolled his eyes from left to right, and then from right to left. The doctor said sharply, “Stop it.” He took out his stethoscope and put it against Jerry’s chest.

The comedian shivered. “That’s cold,” he said. “Doesn’t anyone make mittens for stethoscopes?”

“Quiet,” the doctor said, and continued the examination. Finally, he lifted up his patient’s head, put two pills in his mouth, gave him a sip of water, and then eased his head back down on the pillow. He motioned to the ambulance attendants who helped slip Jerry out of bed and onto a stretcher and carry him down the steps. At the front door they stopped for a second and Patti bent over and kissed Jerry on the forehead. When she straightened up, Jerry winked at her and stuck out his tongue again. And then they carried him out to the ambulance.

Patti waited at the door until the sound of the siren had faded in the distance. Then she went back upstairs, told Gary and Ronnie that everything was going to be all right and that they should go to bed. She stood for a moment by Scotty’s youth-bed and Chris’ crib. Neither had heard the siren; both were sleeping soundly. She pulled Scotty’s blanket up over his shoulders and pushed Chris’ Teddy bear to one side of his crib. Then she switched off the night light and left their room.

Back in her own bedroom she went over to where Jerry had been lying just a few minutes before. She straightened the top sheet, gently, as if he were still there. Then she sank down on the bed and buried her face in the pillow. It was still a little warm from Jerry’s head and a little wet from the water she had splashed in his face. For a long time she lay there, sobbing. At last her crying stopped. Then she turned over on her back and stared at the telephone. She touched the St. Christopher medal she wore around her neck. Jerry had given it to her before they were married—one for her and one for him—and they had both worn them ever since. She touched the medallion, and gazed at the telephone, and waited for the call from Dr. Levy. . .

In the hospital corridor Jerry woke up. “Where am I?” he asked. “This looks like one of the sets from ‘Rockabye Baby.’ ”

“You’re in Mt. Sinai Hospital,” a nurse answered, “and you must be quiet, Mr. Lewis.”

“Quiet,” Jerry said, “why I’m on the board of directors here. You’d better look out or I’ll use my influence and force them to make you my private nurse.”

“Please, quiet, Mr. Lewis,” the nurse said.

Jerry started to answer but his words were lost as the ambulance attendants shifted him from the stretcher to a wheelchair. An orderly wheeled him into an elevator and he was taken up to the fifth floor to room 514. A nurse and an orderly helped him into bed.

One of the resident physicians and Dr. Levy came in and examined him again. Then they put more pills into his mouth and soon he was asleep.

Dr. Levy called Patti and told her that Jerry was resting comfortably and that they would have to wait a few hours before making a definite diagnosis, and he told her to get some sleep.

“Yes, doctor,” she said, “I will. Thank you.” And then she hung up. But even though it was only 6 a.m,, she dressed and went downstairs. She worked around the kitchen, straightening things that didn’t need straightening, washing a few dishes Jerry had left in the sink the night before. And every once in a while, without even knowing what she was doing, she would touch the St. Christopher medal. . . .

When Jerry woke up, a nurse was sitting in the chair next to his bed. “Hi,” he said, “you’re definitely not my wife. Who are you?”

“I’m your nurse, Mr. Lewis.”

“What’s wrong with me?”

“That’s up to your doctor—Doctor Levy—to tell you.”

“Where is he?”

“He’ll be here soon,” she answered. “Would you like something? Is there anything I can do for you?”

“Yes,” he said, “I want to call Patti . . . my wife.”

“I’m sorry,” she answered, “but you’re not allowed to make or receive any calls. That’s doctor’s orders.”

“Impossible,” he said.

“I’m sorry; those are my orders.”

“Do you have orders to starve me until I confess?”

“You can eat,” she answered. “But before that . . . how do you feel? Any pain?”

“A little,” he said, “here in my chest . . . and a bit in my stomach, but nothing that some orange juice, bacon and eggs, fried potatoes and a heap of toast, couldn’t fix. Coffee, of course.”

“But it’s two-thirty in the afternoon,” the nurse said, “much too late for breakfast.”

“Afternoon?” said Jerry, scratching his ear. “Okay, it’s afternoon. Then I want some chili. I suddenly have a craving for chili. And I crave a chocolate malted. With vanilla ice cream. Gosh, maybe I’m preg . . .”—but the nurse interrupted by sticking a thermometer in his mouth. Then she left the room.

A few minutes later she came back with a tray and set it down across Jerry’s bed. Each plate was covered by a metal pan. She took the thermometer from Jerry’s mouth.

He lifted the first cover and there was a little mound of cottage cheese. The second—a small scoop of mashed potatoes. The third—something that looked like tapioca pudding. And under the fourth was a dish of cream.

Jerry looked at the tray and then at the nurse and back at the tray. “I’m really sick, huh?”

“You’re really sick.”

He pushed the potatoes aside, started to do the same with the cottage cheese, and then thought better of it. “Cottage cheese and sour cream,” he said, “that’s not so bad,” and lifted the cream to pour it over the cheese.

“That’s sweet cream,” she said. “You better get used to it; you’re going to get a lot of it.”

“That does it,” Jerry said, glaring at the plate of cream. “I’m on a hunger strike. As of this minute. I want to see my doctor, any doctor.”

“I’ll see if I can find your doctor,” the nurse said. As she left the room, she saw Jerry stick his finger in the cream, lick it, and make a wry face.

A little later two doctors came into the room. “Don’t beat me,” Jerry said. “See,” and he pointed to the empty dishes on the tray, “I ate it all up. Just to make you happy. I’m really very good.”

“How do you feel?” they asked.

“What’s wrong with me?” Jerry asked. “I couldn’t read the tiny writing on the chart.”

“At this point we don’t know for sure,” the other doctor answered, “but we think that you have a perforated, bleeding ulcer. At least that.”

“At least that,” Jerry repeated. “What else?”

“Well, while you were asleep we took an electrocardiogram—a picture of the action of your heart. There are deviations from the normal. But this isn’t unusual. We’ll have to wait three or four days before we can take x-rays and find out for sure Meanwhile, get plenty of rest.”

“And lots of sweet cream,” Jerry added.

“And no visitors except Patti.”

“But . . . but . . .” Jerry said. A thermometer was put in his mouth, stopping his words.

The doctors left. The nurse looked at her watch and Jerry started to take the thermometer out of his mouth. She shook her head no. He picked up a pencil from the table next to his bed and printed on a piece of paper: HELP. I’M A PRISONER IN A SWEET CREAM FACTORY. CALL THE POLICE. He held the paper up for the nurse to read, folded it into a paper airplane, and threw it out of the window.

At last came the day when x-rays were taken. Then he was told the results. “You have a perforated, bleeding ulcer of the rear wall of the stomach,” Dr. Levy told him. “You did not have a heart attack and we can see no damage to your heart. But an ulcer in and of itself, especially the kind you have, is very serious. If you do what we tell you, if you follow orders, you’ll be all right.”

“Uh! Uh! I see more sweet cream coming,” Jerry said.

“No,” one of the doctors said, “you can eat more—if it is bland. No drinking. No smoking. And you’ll have to cut down drastically on work. No 17-hour a day schedule. No working all day at the studio, all night at home, and squeezing in benefits besides. No tension and excitement.”

“No nothing,” Jerry added. “Fellows . . . physicians . . . men . . comrades . . . you’re asking me not to be me. I can’t take it easy. I don’t know how.”

“You’d better learn,” the doctors said and they left the room.

On the morning of his fifth day in the hospital, a nurse’s aide pushed a cart into Jerry’s room. On it were the usual hospital gifts that patients might buy: books, candy, toys, and magazines. “I’ll buy it all,” Jerry said. “And I want to borrow the cart.”

“But Mr Lewis, I can’t give you the cart. It’s against the rules.”

Jerry took out a copy of a Mt. Sinai brochure. “Do you see this?” he asked, pointing to a page. “There’s a list of the board of directors of this hospital. And whose name do you find here?”

“Jerry Lewis,” she read.

“That’s right. That means I’m a boss. One of your bosses. So may I have the cart, nurse?”

So Jerry went from room to room on the fifth floor of the hospital, distributing presents. As the cart’s load lightened, he would push it fast along the corridor. When it was going at a good speed, he would hop on the back and coast along.

Finally, a doctor stopped him and escorted him back to his room. “I was having so much fun,” Jerry said, “and you spoiled it.”

That night, even though the “No Visitors” rule was still in effect, Jerry arranged for Danny Thomas, Jimmy Durante and Sammy Davis, Jr.—his good pals—to slip into his room. When his nurse made her usual nine o’clock visit to take his temperature, the light was out and he seemed to be sleeping. She put the thermometer in his mouth. He sat up quickly. It wasn’t Jerry, it was Jimmy.

“What kind of hotel is this?” Durante asked. “Can’t a man even take his beauty sleep without being innerupted by tourists?”

The nurse ran from the room, and Danny and Jerry came out from behind a curtain, laughing. Jimmy took out the thermometer, put it carefully in the glass next to the bed, pulled the sheets back over his head, and started to snore. It took the head nurse and an interne to “wake him up.”

In the days that followed Jerry “rested.” One evening he called Katy Jurado, who was in the hospital for a check-up, and asked her to “split a bowl of sweet cream” with him for breakfast the next morning. When she arrived at room 514, he was thumbing through a pile of scripts. “I got a great idea for a movie about a hospital,” he said. “I’ll play a double role: a psychiatrist, and a mental patient who looks like a psychiatrist. Now the patient locks up the doctor in a closet, puts on the psychiatrist’s clothes, and starts to make his rounds. Now, he meets a beautiful young nurse—you’ll play that part—and he . . .”

“Enough,” Katy laughed. “Eat your sweet cream before it turns sour.”

“Hey, that’s a great idea,” Jerry answered. “I’ll leave the sweet cream standing around for hours and then it will become sour cream. I like sour cream. . . .”

“Jerry, stop,” she said. “You’re making me ill.”

That afternoon Patti and the boys came to visit him, but his younger sons still weren’t allowed in and had to wait across the street. Jerry had a camera with a telescopic lens. He leaned it on the window sill and looked through the lens at the boys.

“Patti,” he yelled, “I can see them big as day. Hey, Chris has a new tooth. And Scotty . . . why he’s wearing one of my ties, my favorite tie. I have to get out of here before he finds out my suits fit him, too.”

One afternoon Jerry borrowed a doctor’s uniform and went down to the children’s ward. “I’m Dr. Lewis,” he told the youngsters, “and I have medicine for all of you.” He distributed candies and toys to all the kids there. One little girl was too sick to say anything to him, but she smiled wanly as he put a rag doll in her arms.

Later that evening, he called Patti on the phone. She came to the hospital by taxi and went straight to his room. “Patti,” he whispered, “Patti.” And then he just looked at her for a minute, in silence. “Patti,” he said, “I’ve been doing a lot of thinking. I’m going to try my best to slow down a bit. It’s hard. I love my work. I love to make people laugh . . . But you know all that.

“I’ll cut down, yes. I’ve learned my lesson. But there are certain things I won’t cut out. That telethon for Muscular Dystrophy, for instance. I’ve been doing it for about ten years. I can’t stop now. I don’t want to stop.”

An expression of acute pain, of deep sadness, flitted across Patti’s face. Jerry’s fingers gripped her arm. “No, Patti, no tears. No. No. No. No. You misunderstand me. It’s just that . . . well, I saw a sick little girl this afternoon. She doesn’t have MD but she had something just as bad. I can’t stop helping kids like that. If I did stop, then it would kill me.”

Patti bent over and kissed him. “Perhaps they could postpone the telethon until you’re a little stronger,” she said. Then she put her head down next to his on the pillow. His arm circled her head and he closed his eyes and pressed his face against her hair.

The nurse entered the room, thermometer in her hand. “Oh, no,” Jerry said, “not now. Look. I’m going home tomorrow. So be good No temperature-taking. No sweet cream. Be good or I’ll call Jimmy Durante to come over and scare . . .” But he never finished the sentence, for the nurse popped the thermometer, gently but firmly, into his mouth.

THE END

DON’T MISS JERRY IN PARAMOUNT’S “DON’T GIVE UP THE SHIP.” WATCH FOR HIS “SPE- CIALS” ON NBC-TV.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MARCH 1959

AUDIO BOOK

No Comments