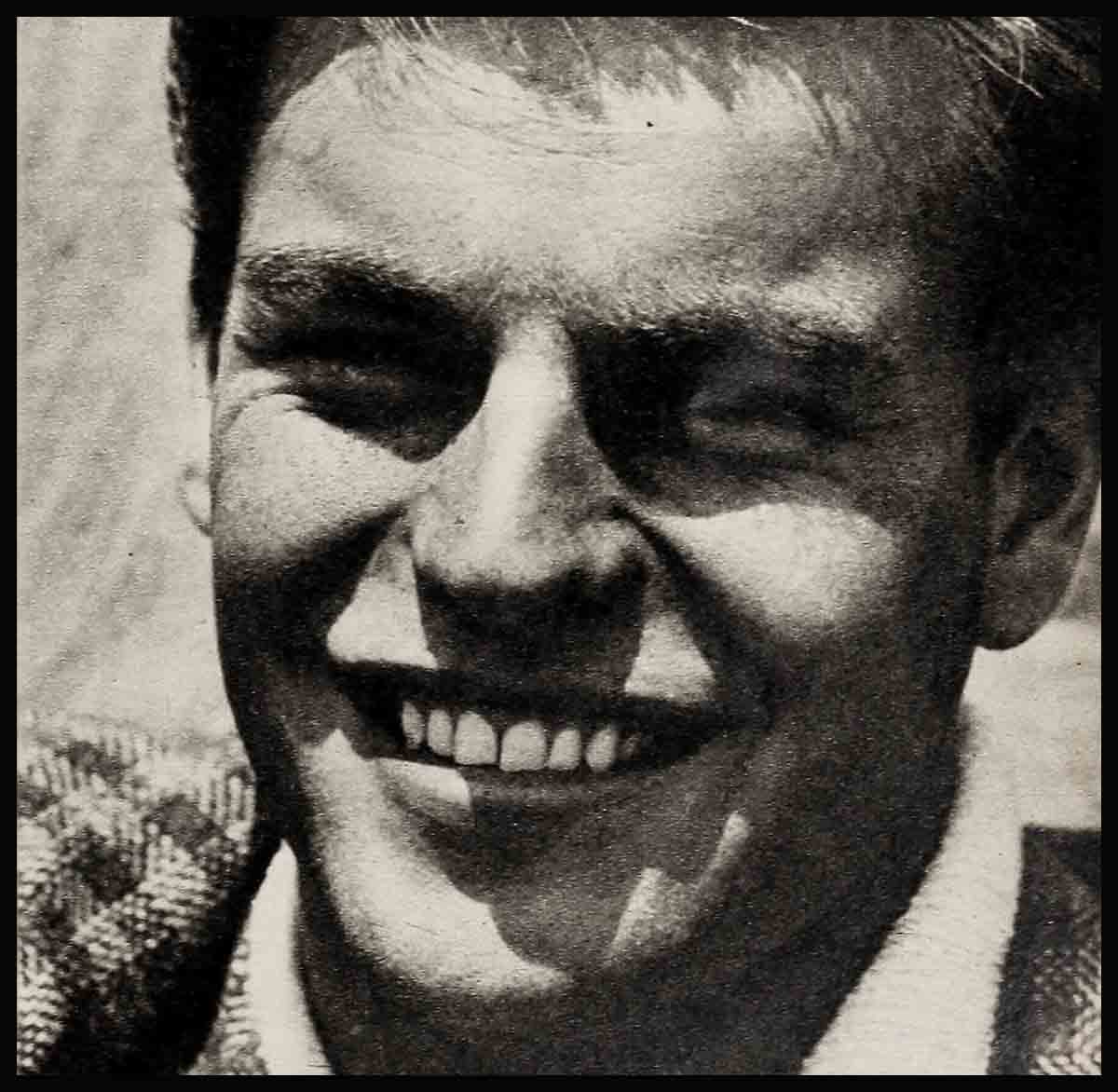

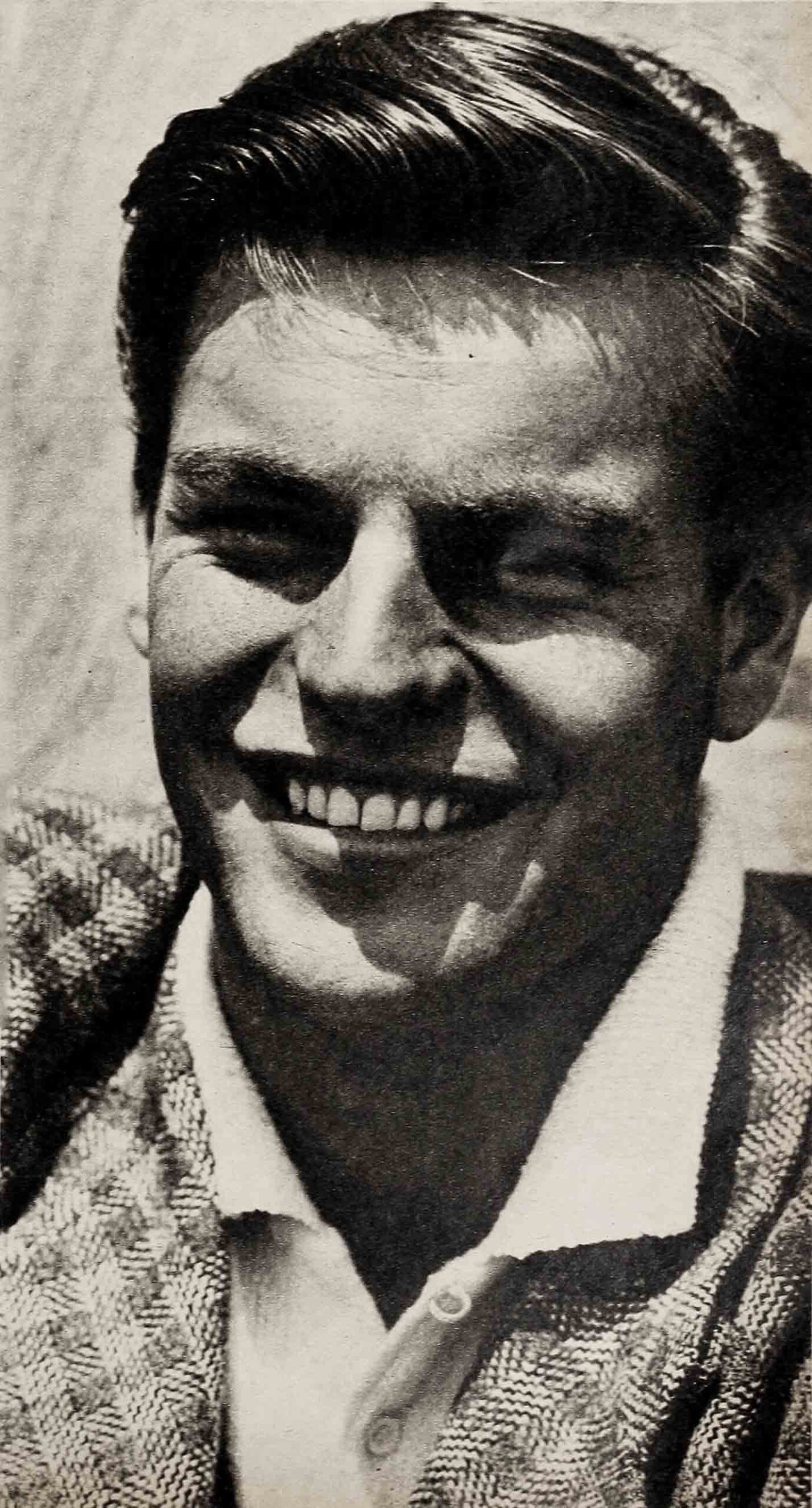

Quiz Kid—Robert Wagner

“Say !” hailed the tall, grinning kid, strolling in from the fairway’s edge and up to the Bel-Air foursome. “Want to buy a ball?”

One of the golfers extended his hand. “Let’s see it, R. J.,” he said, and inspected the proffered pill, which was hardly a prize in any self respecting linksman’s book. The paint was cracked and on the cover, where a vicious iron had topped it, there. was a smile almost as big as the one on the face of the tow-headed scavenger.

Randy Scott, who was the golfer accosted that day, started to shake his head but he knew he didn’t have a chance.

“Let you have it for a real bargain,” pressed the determined young salesman. “Two bits. I need the dough. Got a date. Thanks!” He caught the spinning coin and hustled off toward the thirteenth green, ducking through the hedge and across the street. That’s where Robert John Wagner, Junior, lived. In a sec he had swung aboard his bike and was pedalling down the hill to pick up a cutie whom he had promised a double-jumbo malt at Tom Crumplar’s in Westwood Village.

A scene like that was pretty common around the Bel-Air Country Club about ten years ago. when Bob Wagner was twelve years old and by summer profession a caddy. To tell the truth, he wasn’t too hot a caddy for a couple of reasons: one was that packing bags and spotting balls for such movie star members as Bing Crosby, Clark Gable, Randy Scott, Fred Astaire and others, Bob was inclined to rivet eyes on his employers in a worshipful manner instead of on the balls they smacked. so usually the balls got lost. And then, just as a player Started a backswing designed to wham out a 300-yard drive, “R.J.,” as they all know him, was prone to paralyze the project by inquiring, “Say, Mister Gable, about that scene where you socked the guy and drove off with the girl: How could you shift gears with your hand around her waist?”

“The Quiz Kid” they called him and sometimes they’d quiz him back. “What you collecting all this studio dope for, R. J.? Going to be a movie star when you grow up?” But they’d scan appraisingly the sculptured features, handsome eyes and flashing smile of the curious kid even as they razzed him.

“I don’t know about that,” Bob would state seriously. “But I’m sure gonna be in the picture business someday.”

By now Bob Wagner has done just what he said he’d do. He’s in the picture business, and in solid. Not as a star, yet, although he’s zooming that way with the speed of an F-86. Already he has six pictures to his account; and such varied roles as the touching shell-shocked paratrooper in With a Song in My Heart and the comic Willie in Stars and Stripes Forever. Bob has earned the rave praises of everyone who’s worked with him, including his boss at Twentieth Century-Fox, Darryl Zanuck, who calls his big boyish actor, “the freshest and most promising young personality we have on the lot.”

All this is no surprise to the locker room at the Bel-Air CC where Bob still hangs around every spare moment and where by now his status is considerably changed. The skinny caddy who was just “Dude Wagner’s inquisitive kid” has sprouted to six foot-plus, his cornsilk mop has deepened to brown, he strips down to lean, hard muscles and has to shave his long jaw every day. He’s twenty-two and a man. The aging idols he used to caddy for are often his golf partners today and he gives them a hard.time on the course with his sizzling game.

But when he breaks it up by taking off in his maroon convertible, grinning, saying, “So-long. Have to run. Got a date,” he gets the same affectionate razzing he used to. They call him “Lover Boy” then and “the Beau of Bel-Air” and sometimes his dad’s favorite tag, “Dynamite.”

In another respect Bob Wagner hasn’t changed. They still call him “the Quiz Kid,” because he’s still eternally asking questions, not only around the club but wherever he goes. In fact, as he departed just the other day, a member cautioned “Better be nice to R. J., boys. Hell be hiring you some day. I never saw a kid so movie crazy. He used to be, he is now and believe me, he always will be!”

But in less informed circles, until recently at least, Bob Wagner has been sold short. Because he’s so young, so glib, sociable and easy going, because of his social and well-to-do family and his private school and country club boyhood, and because he does like the ladies, notably Debbie Reynolds, the portrait of young Robert Wagner around Hollywood has too often been drawn as a butterfly playboy dabbling in pictures for the glamorous heck of it. Nothing could be more cockeyed.

It’s true enough that Bob’s a hometown boy and that he had plenty of top echelon Hollywood connections who could and did help him get a break. But there have been more hollow headed pretty boys with pull than you could dig out of Hollywood oblivion with a bagful of niblicks, and actually the hometown ones have always found it rougher than the rest to hole out their opportunities at a studio. Bob Wagner has made his shots stick at the flag, and he’s driving straight down the fairway today only because he knew what he wanted and went after it aggressively, sensibly and for real. Being blessed with the native curiosity of a litter of kittens hasn’t hurt him, either.

Since he arrived there three years ago, Bob has been prowling around the Twentieth Century-Fox lot like a tourist, poking into the cutting rooms, prop sheds, wardrobe racks, recording and dubbing stages, portrait galleries, even the paint shop, pestering people with “how come” on details about how movies are made. On all of his six jobs he’s arrived with time clock precision throughout the picture, to watch and learn, even though sometimes he worked only a couple of days. He hauled home both a tuba and a sax making Stars And Stripes Forever and kept his Bel-Air neighbors awake nights until he could look like one of Petrillo’s boys in the Sousa band. Though his part was brief, he cornered Jane Froman herself, out to record “With A Song In My Heart” and pumped her with questions once for four straight hours until that game gal gasped, “Well, Bob, now that you’ve got my life story, how about telling me yours?”

Already Bob has snatched two chances to cover the country and meet the people. On his tour, of 80 cities after Let’s Make It Legal, Bob got a call from a girl in the lobby of his New York hotel. She said she’d like his autograph. He told her to come right up, and, when he opened the door, 45 filly fans of his pranced in. He lost a gold pin, two shirts, three neckties and a cherished trench coat in the melee, but he was very happy about the whole thing. “I found out more about them than they did about me,” he gloated. Returning by train from another COMPO tour recently, Bob struck up a gabfest with a stranger, naturally on the subject of Hollywood and the movies. Through a couple of states, Bob held forth enthusiastically on the glories of the picture business until his club ear companion finally asked him, “Say, what’s your racket out there, Bud? Press agent?”

So the locker room man was right. Bob Wagner is movie crazy. But, I submit, crazy like a fox. At Helena Sorrell’s drama coaching department, for instance, Bob Wagner is such a standard fixture that she calls him “My Boy.” Bob has haunted her so thirstily for instruction that he’s made 56 tests with young hopefuls on his own time and by now can build up his scenes like a Barrymore. In fact, that’s just what he did not long ago with very constructive results.

They had an option test coming up for a girl starlet, whose contract was on the shaky side, so Helena, Bob and Jeffrey Hunter got their heads together to make a miniature movie which could keep her stock soaring with the big bosses. Jeff played a suave older smoothie and Bob a bumbling, boyish lover with the girl in the middle of the contrasting suitors. Well, once Wagner got started on the funny business of bashful love the test grew and grew, because about every day Bob would come-up with “Look, I got an idea,” which was so funny they just had to keep it in. But when they finally screened it for Darryl Zanuck, the outcome was gratifying, indeed. Not only did the girl get her contract renewed but Zanuck, impressed by Bob’s comedy, scratched Rory Calhoun’s name from the Stars And Stripes cast sheet and pencilled Bob Wagner in for Willie, his biggest part yet. So spreading yourself can pay off when you least Suspect it, and that’s what Bob Wagner has been doing just naturally ever since he was addressed and delivered to Hollywood at the tender age of seven.

The above is no idle figure of speech, because Bob actually did travel to Hollywood with a tag tied to his coat button reading, “Deliver this boy to Mrs. Pierce, Hollywood Military Academy, Hollywood, California.” After printing those instructions, his dad boosted him up the pullman car steps, and slipped ten bucks to the porter to see Junior safe to his destination, all by himself via the Atchison, Topeka and Sante Fe. Young Bob made the trip without even one mishap!

The reason for this hurry-up juvenile solo was to get Bob under the wire for the California fall school term. His older sister, Mary Lou, was already in school there at Marymount and the whole family was due to follow as soon as R. J. Senior, who had been successful in the paint business, could retire and enjoy life in sunny Southern California. But first there were business and household matters to wind up in Detroit, where Robert John Wagner Junior was born February 10, 1930.

Even at seven both Bob’s athletic body and passion for sports had already got off to a pretty strong start. The first home he remembers was on Fairway Drive, just a mashie shot away from the second hole of the Detroit Golf Club links, and he played around with a putter and golf balls before he could walk.

Bob started his long list of schools at Brookside, a Detroit private academy for refined little gents, but summers he shook himself loose at the log cabin Wagner summer home on Northport Point by the lake. Exploring the wonders of the world there, he survived kicks from the family pony, canoe duckings, tumbles down sand dunes and one wild swing with an axe which almost chopped off his foot instead of the tree he’d aimed at. But finally he learned to swim, ride and fish and eventually hauled in the biggest catch yet pulled out of the bay, although his dad had to hold him in the boat to keep it from being vice versa.

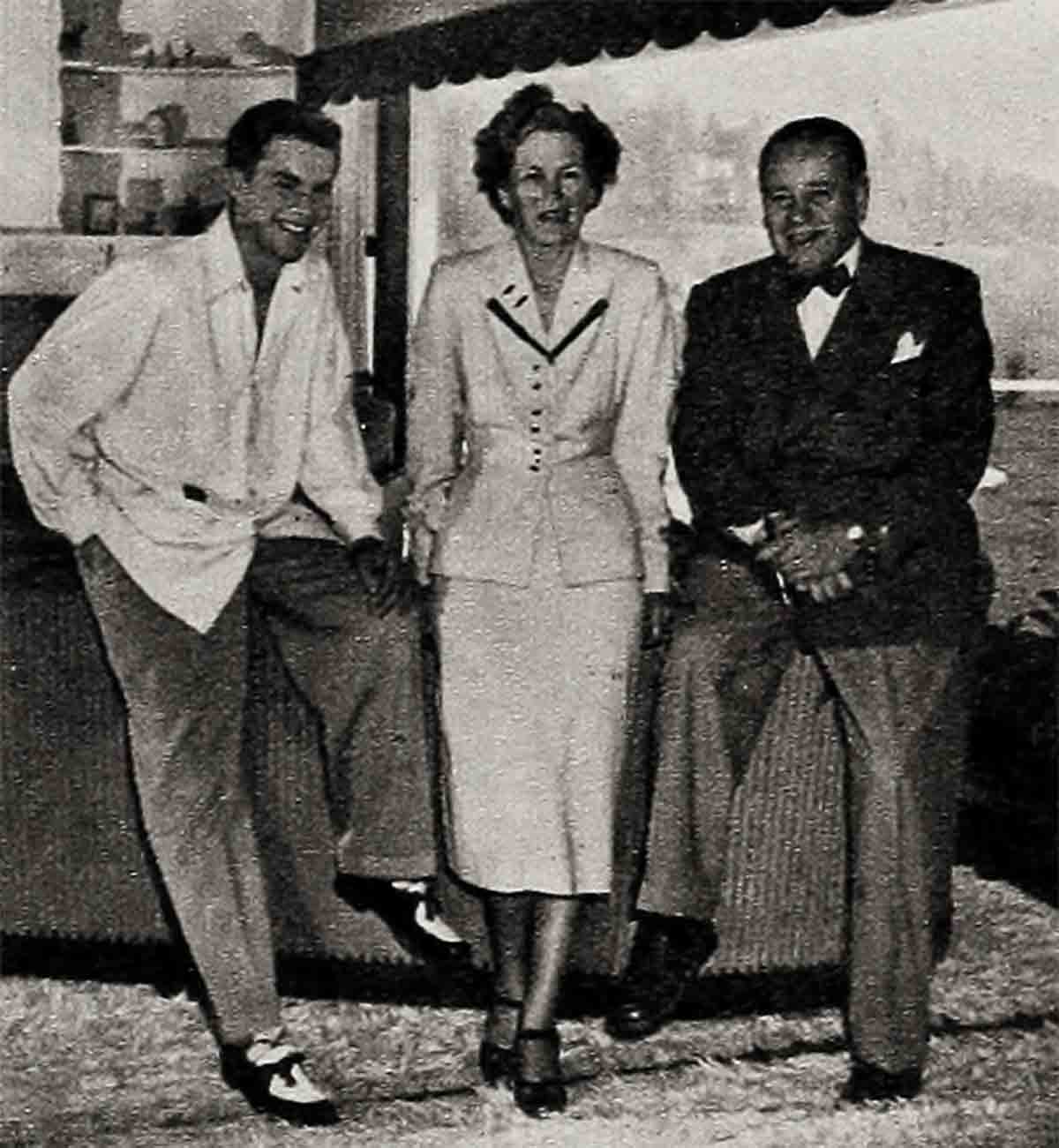

Bob remembers a boyhood full of adventure that was marred by few restrictions on his personal freedom. He’s always been pals with his father and mother and they’re still his best friends. There’s an easy going, relaxed, joking but affectionate relationship between Bob and his folks today that testifies to their sound, understanding job of raising a boy. “We just guided R. J.,” his father admits, “we never reined him in. But, to tell the truth, he never needed it.” That doesn’t infer by any stretch that Bob was ever a pantywaist or a sis. On the contrary, from the start Junior Wagner got mixed up in all the rugged outdoor sports that California offers its sons.

Headquarters was the house his dad built by the Bel-Air golf course and later switched to the old Bel-Air stables, now the swank Bel-Air Hotel, where another kid who craved excitement named “Dare” Harris, now known as John Derek, kept a horse and a BB gun. Bob acquired the same equipment.

“We declared war immediately,” he reminisces fondly, “and had point-blank battles all around the stalls.” When that palled, they carried the skirmishes up and down the Bel-Air hills, hoss-opera style, until Bob got shot in the mouth and his mother took away his artillery.

The surrender channeled him into a more safe and sane athletic program, which, with the Club so handy, was easy. In no time Bob was pretty slick at golf, tennis, and swimming, and you can spot this training right away when you see him today, in the graceful way he moves

and his long, streamlined build. When his dad acquired a ranch in the San Fernando Valley and stocked it with horses, Bob devoted himself to collecting all the cups and trophies for equestrian skill around. Los Angeles County. Today he’s got enough scattered around his room to start a small hardware store. And then there were all the campus sports—basketball, baseball, diving, football. Bob was on so many teams he can’t remember them, but, for that matter, he went to so many schools it’s hard to recall all those, too. In fact, Bobby Wagner piled up what must be an all-time, all-California record for campus trotting until he finally graduated from Saint Monica’s at eighteen. “I made them all,” he admits, “all except reform school. I can’t understand how I missed that.”

Bob blossomed most, though, at Cal-Prep, where the system was to treat boys like men. Students were on their own there. They could smoke in their rooms, buddy with the profs, manage their own study time, ride their own horses. Up in the Ojai Valley, Bob settled down, became an activity man and a member of the student body council. He wound up being senior class president at Saint Monica’s, where homesickness for his folks and Hollywood brought him back for his last year.

All this private education may smell like money, and it’s true that Bob Wagner’s family has never been on relief and probably never will be. But the picture of a pampered rich boy doesn’t fit R.J., and it burns him to a crackling today when that’s how he’s painted. Bob’s dad isn’t and never was a rich man, but a successful business man who made a good living and still does. Although he arrived in California to take it easy after piling up some security, sitting around in the sun soon drove him wild, so he got back in the paint business again, switched to steel and now represents several Eastern companies on the Coast. Self-made himself, he has always plugged that idea with his son.

“We had a deal,” Bob says. I earned, Dad would match it. But I had to earn something first or it was no dough.” From his caddy days on, Bob never missed wangling a summer job.

Frankly, Bob Wagner likes the girls and the girls like him and it’s a pretty old and mutual habit. As far back as his Harvard Military School days he was going steady with pretty Sue Moir, just as he is today with sweet-faced Debbie Reynolds. In between Bob has enthusiastically lived up to the courtly nicknames they still toss his way. With his charm and looks it would be a shame if he hadn’t. Like everyone else, a lot of his dates told him, “You ought to be in pictures,” and a lot of them knew what they talked about. Among his first girl friends were daughters of first line Hollywood families—like Gloria Lloyd, who’s Harold’s daughter; Melinda Markey, who’s Joan Bennett’s, and Michele Farmer, who calls Gloria Swanson “Mom.”

His own family, too, had scads of Hollywood friends stemming from the days when R. J. Senior sold paint for movie sets and traveled around the studios. The Wagners’ long standing as Bel-Air Club members too, where Bob’s dad is on the board, had established them in a social set that takes in an important part of the movie colony. Wherever Bob turned he could find someone, young or old, with a studio connection—like one of his best friends, Jack Anderson, who married Joan Bennett’s other daughter, Diana. And they all were eager to say, as Jack did one day to Solly Baiano, the Warner casting chief, “I know a kid named Bob Wagner who’d be great in pictures.”

“Send him out,” said Solly.

Now that happens all the time to good-looking young men in Hollywood who have the right entree. So there’s no point in saying that-Bob Wagner’s chance came hard. But making the chance pay off is strictly another thing. Bob went out to Warners, for instance, and nothing came of that. He traveled around the studios a lot on introductions but, after all, what did he know? Facing up to it, Bob came right back to the bleak fact that as far as dramatic experience was concerned, all he could point to was a military school playlet, The Life Of John Alden, in which he played—hold everything—Priscilla!

That’s why it was easy for his dad, who had a business career for Bob in mind, to argue logically that he should take a crack at the steel game when he graduated from Saint Monica’s. That Easter vacation R. J. Senior took Bob on a tour back East, to all the steel mill towns, to show him what it was about. That summer he hired him on as a junior salesman and for a while Bob did his best. But then one day he had to let his dad have it:

“It’s just no good,” he told him. “I’ve got this picture business in my system and I’ve got to either get it or get it out. How about it? Will you stake me for a year while I try?”

R. J. Wagner had been a sportsman all his life. “I’m your dad, aren’t I?” he grinned. “Tell you what. Bill Wellman’s Starting a picture. I’ll ask him what he can do.”

Wild Bill called from MGM two hours later, “Get on out here, R. J.,” he ordered. “We’ll make you an acior.” But of course it wasn’t as easy as that.

What Bob did was a tiny bit in The Happy Years, a baseball catcher to be exact, with a grilled mask over his face. He said, “Come on, pitch it down here!” and probably he didn’t say it very well. But that didn’t matter. Bob Wagner was up in the clouds. He was in the picture business, officially at least.

Of course, that brief exposure really Meant nothing at all. Bill Wellman doesn’t make pictures all the time, for one thing, and Bob Wagner wasn’t out after one-line parrot bits anyway. He knew he was gourd-green, but he wanted to set about this thing right. A lot of people gave him good advice—John Hodiak, whom he’d caddied for; Alan Ladd, whose daughter Carol Lee he’d dated; dozens more. Their counsel was sound: Get an agent, get experience, get into some little theatre Shows. Go on, just do it. But easier said than done. Bob was still asking questions but not getting the right answers, and the months were slipping by when suddenly the lightning struck. A piano-playing friend of his, Lou Spence, was trying out some material at the Gourmet restaurant in Beverly Hills, and Bob and his folks went there for dinner. Bob likes to sing, has a good voice, too. So between courses he leaned over the piano with Lou and joined in on “Tea For Two.” That’s when the waiter brought the note: “If you’d be interested in picture work, come see me at the office—and better bring your parents.” Bob looked that young, and he was, just nineteen. The talent spotter was Henry to name a few. After Bob called around, with his dad to the Famous Artists office the next day, things started rolling fast.

Before he knew it, he was up for a test at Fox, doing a love scene with pretty Pat Knox and perspiring so profusely he had to take a shower afterwards. “They still call me ‘the sweater’ out there,” Bob grins. But getting all hot and bothered paid off. He won a four month option. In other words a “You look good, we’ll see, hang around.” But Bob was too steamed up for that passive role. Henry Willson routed him right away to MGM where a free-for-all elimination contest was going on—the prize, a lead in Teresa. Fred Zinneman was screening a hundred-odd young actors, some pulled clear out from Broadway, for the part of a young psychoneurotic. “For me,” Bob allows, “that was easy. I was so nervous I was a psychoneurotic!”

Anyway, he emerged from the contest definitely the red hot favorite, and word like that gets around. Fox didn’t let his option dangle any longer. They put him right on the team and four weeks later he was playing the beardless Marine in Halls Of Montezuma which came easy too, because Bob had just seen a stretch of service with the USMC Reserve.

Since then, in The Frogmen, Let’s Make It Legal, With A Song In My Heart, What Price Glory and Stars And Stripes Forever, Robert Wagner has pretty well proved it was no crazy kid idea that propelled him toward the picture business back in his caddy days. While none of his jobs yet.is anything to cop an Academy nomination, they’ve earned him the tag, “a young Montgomery Clift,” and a bundle of bouquets from far and wide.

But, if there have been some swift and important changes made in Bob Wagner’s Hollywood prospects, there are very few alterations evident in R. J. himself. He’s still pretty much the friendly, grinning inquisitive guy, with his eyes roaming around looking for fun and excitement. Being an eager beaver hasn’t made Bob a dull boy. It’s safe to say that R. J. Wagner has more friends and less enemies than any unattached young male in town of all ages and stages of Hollywood eminence.

He’s a familiar fixture at the homes of John Hodiak and Anne Baxter, Richard Sale and Mary Loos, the writers, the Dick Widmarks, Clifton Webb—all older than Bob—and a particular pal of “Dooley” Dan Dailey’s. The young married set, like Dale and Jackie Robertson, Jeff and Barbara Hunter and Rory and Lita Calhoun keep him just as busy, and young unmarried set (female) even busier. Or perhaps it’s the other way around.

Bob occasionally spreads his favors among Barbara Darrow, Melinda Markey, Pat Knox, June Haver, Anita Eckberg, and Susan Zanuck—to list a few, When Dan Dailey became a bachelor-about-town a while back he immediately buttonholed Bob “You really can’t use all of that talent yourself, Lover Boy,” he ribbed him “Com on, give us a look at the little black book!”

Bob takes the gag goodnaturedly, but actually the wolf skin doesn’t fit. In fact, Bob thinks it’s some kind of a crazy joke to call him a Casanova on the $35 his dad doles him out weekly from his studio paycheck. If there is any serious heart interest for Bob, of course, it’s Debbie Reynolds who first met Bob right on his own studio let and immediately tabbed him “a real crazy cat.” By now Debbie knows different. In fact, she’s the biggest booster Wagner has. “A serious, sensitive actor, this boy,” she’ll tell you today, and Debbie ought to know.

They’ve been chasing to movies (still Bob’s favorite form of entertainment) practically every date of the world, and so far the most furious battles they’ve had have been who was good and who was lousy in the show and why. Actually, Debbie Reynolds and Robert Wagner are pretty much in the same Hollywood boat. Both are homegrown, both tackled Hollywood as green as grass and both have come through—Debbie further than Bob and a little faster, but as she says, “Just stick around.” You get essentially the same answer when you ask either one about such things as engagement or marriage. “Just not on the docket for either of us, that’s all,” Bob says frankly, “although there’s no one like Debbie. She’s great—just great.”

While Bob’s attractions for the girls are obvious—he’s a snap dancer, tailor’s dream and keeps them laughing with a running patter of very funny talk—feminine attractions for Bob fit only part of his program. He’s still a great family boy, goes fishing with his dad, and squires mother to dinner and shows just like any younger date. The athletic kick he’s owned since infancy still gallops strong in his blood, and he could no more get along without his golf, tennis and swimming than he could without the bushels of food which make his mother despair, “I can feed R. J., but I can’t fill him.”

Bob will have to take on that problem himself in short order. Because the Wagners are leaving Bel-Air soon and moving south to LaJolla where R. J. Senior can take things easier as he’d planned to 15 years ago. Since coming back from Camp Cooke and his Army Reserve service last summer, Bob has-started hunting for an apartment for himself and his cat, “Rudy,” but nobody around the Wagner household is worrying about Bob’s being lonely or starving to death.

The only qualms that Mr. and Mrs. Wagner nurse about casting R. J. adrift are the accidents that seem to threaten his life and limbs whenever he leaves home. Up at Lake Arrowhead last year Bob was water skiing double with his pal, Jim Aubrey, behind Dan Dailey in a speedboat at 30 m.p.h. when he spilled, and Jim, on the long rope, cracked into his head, knocking him out cold: and sending him plummeting to the bottom like a rock. Jim pulled him out in time, but Bob reaped a brain concussion, also a split ear drum, and he’s had migraine headaches ever since.

Then, travelling out of Chicago on the train, the engine smacked an automobile at a grade crossing and the wreckage almost flew in the window of Bob’s roomette. And there was that car crash Easter Sunday on the Coast Highway riding with Susan Zanuck when a Model-A hot rod smacked Bob’s car broadside for no good reason at all. Luckily, the door flew open and Susie popped out like a cork with no damage, but Bob suffered a severe cut on his eye from the flying glass.

But if Bob Wagner can only keep himself all in one piece, it doesn’t look as if the world around Hollywood will be very cruel to Junior. He knows what he wants and by now it’s pretty certain he has what it takes to get it. And by now too, his old man, who at one time wasn’t too certain about the latter, is pretty confident and proud of his namesake.

When the steel mills closed down in the Big Strike a few weeks ago R. J. Senior had time at long last to see Bob in action. He strolled on the set of Stars And Stripes Forever, watched fascinated as his son emoted, and then strolled off arm-in-arm with Bob. “Well, R. J.,” he grinned at the stage door, “I’m glad somebody in the family’s working steady!”

From all the evidence it looks as if Bob Wagner will be working steady around Hollywood for a good long time to come. That is, if he keeps on asking questions and getting the right answers. Already he’s collected the ones that count.

THE END

—BY KIRTLEY BASKETTE

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1952

No Comments