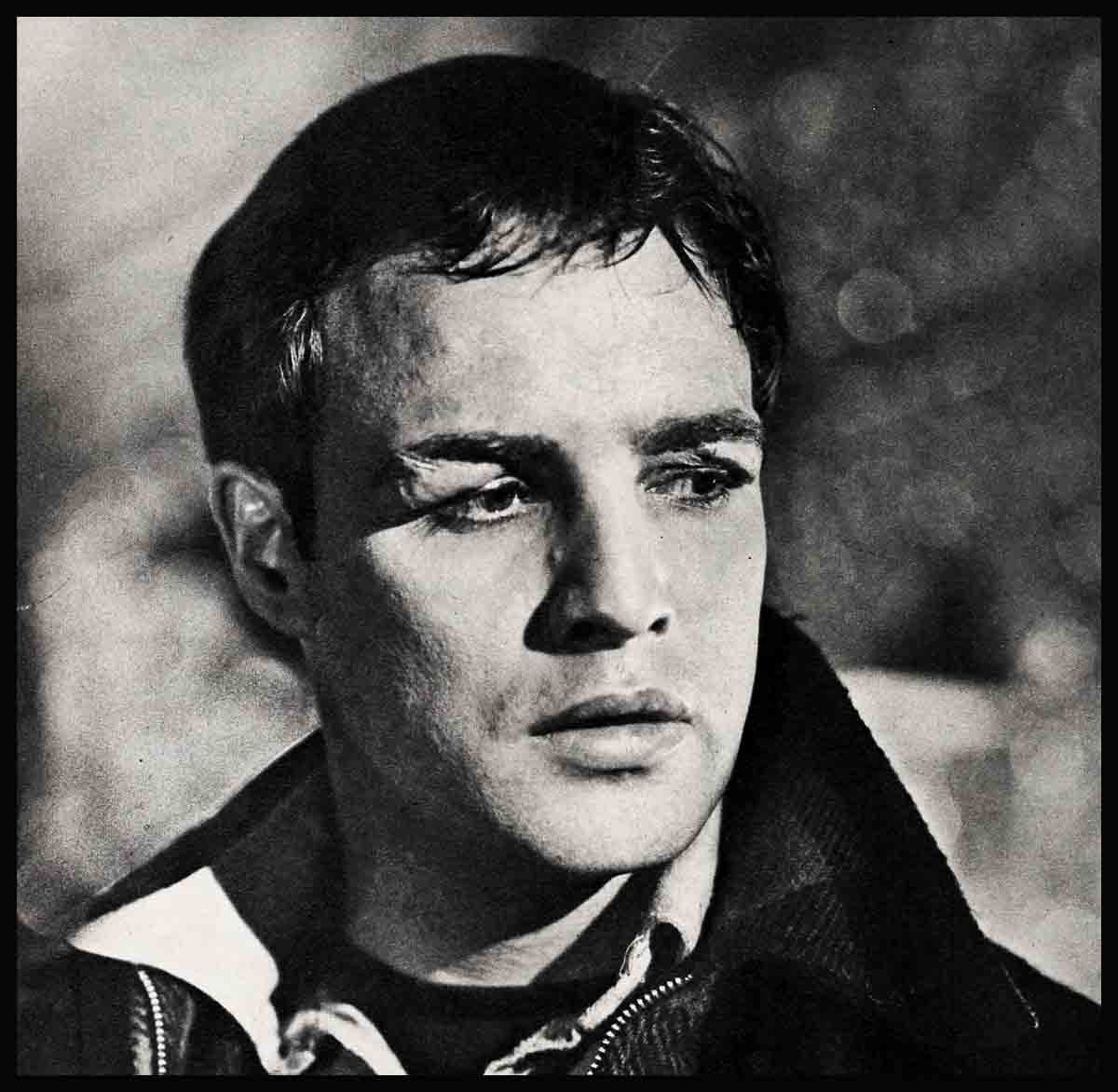

My Friend Marlon Brando

We recently assigned a story on Karl Malden, who gives a superb performance in the part of the priest in “On the Waterfront.” Reluctant to talk about himself, Karl Malden turned: the conversation to. his friend and colleague Marlon Brando.

No other actor has worked with Brando over as long a period of time or known him as intimately as Karl Malden. They met in 1946 during rehearsals for Maxwell Anderson’s “Truckline Cafe.” Subsequently they were together for two years on Broadway in “A Streetcar Named Desire” and thereafter in the Hollywood version of the play, where his portrayal of Mitch brought Malden an Academy Award. At present, and again under the director of Elia Kazan, both appear in Columbia’s “On the Waterfront” and are almost certain to be nominated for next year’s Academy Awards.

THE EDITORS

There isn’t really much I can tell you about Marlon. As I see him, he’s an ordinary guy like you or me—except he’s a genius. No, I’m not kidding you. I honestly believe he’s by far our greatest actor today. He’s completely singleminded about his profession, but aside from his enormous talent he’s no different from anybody else.

There seem to be a lot of people, however, who find it difficult to understand Marlon. They’ve become so used to all sorts of shenanigans and publicity stunts by movie stars that they consider ordinary behavior as eccentric. Just because he doesn’t go in for a lot of nightclubbing, public romances and expensive sports cars, people take it for granted he must be a screwball. I can assure you he isn’t. The key to his whole personality, in my opinion, is that he’s one of those all-too-rare people with enough strength of character to be completely themselves.

If Marlon doesn’t own a car, except a pretty battered old jalopy out in California, it’s because he has no use for one. If he doesn’t go to nightclubs, it’s because he doesn’t enjoy them. I know he owns at least a couple of good suits, but usually he wears a faded pair of dungarees, sneakers and an old T shirt. Why shouldn’t he, if that’s the way he’s most comfortable?

Sure—I’ve been to parties with Marlon when he was dressed very neatly and very well. When he has to go to one, he can be as nice and charming and well-behaved as anyone I know. But he won’t go to a large party if he can possibly get out of it. He doesn’t like to drink and he doesn’t smoke. He does like stimulating talk, but that’s the one thing you rarely find at a party. When he comes to visit us, he either brings a date, or we spend the evening with him alone. We’ll take our time over dinner, talk and later maybe listen to records. He loves music and has a big record collection himself. There’s hardly anyone I know who’s better company than Marlon in a small group.

He’s crazy about kids and usually tries to come early so he can spend a little time with my little girl, Mila, who is six. She adores him, and when he’s with her he acts like a big kid himself. He’ll roll on the floor, romp and dance with her, read or tell her stories—he’s come up with some whoppers—and hatch out more mischief than even she can think of by herself. The last time he was over, he got there before I came home, and when I opened the door, they both jumped at me. The lights were out and they had covered themselves with bed sheets, playing ghost. On the other hand, with our second little girl, Karla, who was born last August, he was as gentle as a lamb. I’ve known a lot of young fathers to be clumsier with their own kids.

He really loves children, and I’ve often wondered why he doesn’t settle down and raise a family of his own. Of course, Marlon’s still quite young—he was thirty last April—and some day I expect he’ll be hit hard and take the dive, but for the time being he seems to prefer playing the field and not tying himself down. When he eventually does marry, I believe it will be for keeps. He probably knows that himself, and I guess he gets cold feet and starts running each time he feels he’s beginning to get himself tangled up.

While he gives the impression of always being on the run, he definitely does not run so fast the girls don’t have a chance to catch up. I’ve seen Marlon date a number of girls, and not one of them fit a set pattern—except that they all had either brains or talent. They were dancers, painters, actresses or secretaries, all of them interesting and some unusual, though not necessarily beautiful. According to his mother he always fell in love with the ugly ducklings of the neighborhood, even when he was still a kid in school. That’s no longer true as far as I can judge, but a girl certainly has to have more than beauty before she can interest Marlon.

Of course, he’s got a terrific appeal for women. When we were together in “Streetcar,” there wasn’t a night he didn’t have a stack of letters waiting for him at the theatre or that he didn’t have to grin his way through a whole cluster of admirers waiting for him at the stage door. They came in all age groups, from bobby-soxers to women of sixty. And that was before he became nationally famous in movies.

Actually the brutish character of Stanley Kowalski he portrayed in the play was quite alien to him. That’s why he was particularly pleased when he aroused the purely maternal instinct in at least one woman. A lawyer presented himself in his dressing room one night, asking him to accept a present from a wealthy woman client who preferred to remain anonymous. Marlon was frankly delighted. He likes to receive presents fully as much as he likes to give them—and he gives plenty of them. At one time he sent a struggling musician friend a grand piano as a gift.

Once when we expected Marlon for dinner out in Hollywood, my wife Mona thought she’d ask another girl to make it a foursome. I don’t want to mention the name, but the girl she asked is one of the most beautiful and sought-after young women in Hollywood. About ten minutes before she was expected she called up to say she was awfully sorry, but that Pamela, her pet poodle, was sick.

“That’s too bad,” Mona said. “We’ve asked Marlon Brando to be your date. I thought you’d enjoy meeting him.”

A few minutes later the girl called back. “I put Pamela in the hospital,” she said. “I’ll be right over.”

With that kind of attention from women, you’d think Marlon would be spoiled and conceited. He’s confident, of course, but spoiled and conceited—definitely not. For one thing, he’s far too sensitive for that. Marlon’s one of the most sensitive people I know. He’s so thin-skinned and so easily hurt, he seems able to sense one person’s hostility or dislike in a crowd of a hundred people. When that happens, his first reaction is to shrink away. On the other hand, he isn’t too proud to make an effort to win people.

I happen to know one of the boys from the paraplegic ward at Birmingham Veterans’ Hospital where Marlon spent four weeks prior to the shooting of “The Men.” Marlon was in a tough spot, a powerful, healthy guy forced to ape and study the poor devils who were paralyzed from the waist down. At first their resentment was like a brick wall. It didn’t take them very long, though, to find out that Marlon was regular. The climax came one night as he was sitting in a wheel chair with his buddies in a nearby cafe when a well-meaning but not very bright lady harangued them with an admonition to pray for help. It’s the kind of thing which—coming from an outsider—is deeply resented by people who suffer from an irremediable physical condition. It’s exactly like asking God to grow a new leg in place of a severed one.

“Pray, boys, pray and have faith,” she admonished, “and you will walk again.”

Everybody was quiet, but Marlon sensed the deep bitterness in his pals. Only laughter could break the rising tension. With a show of making a desperate effort, groaning, pushing himself up on the arm rests of his chair, Marlon struggled to his feet and started stumbling toward the lady. Accounts seem to differ over whether she fainted or fled in panic.

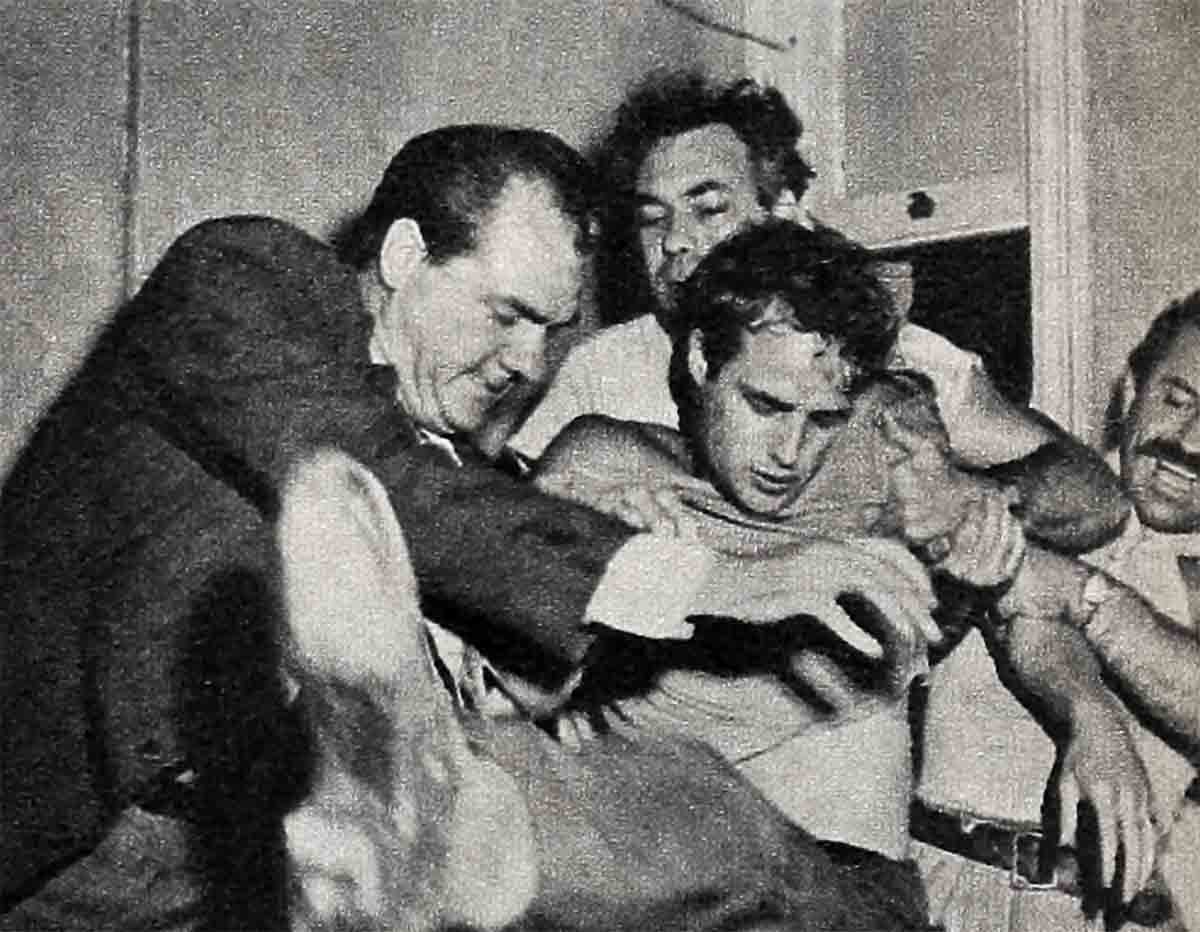

Another example that I witnessed myself I saw on the docks in Hoboken, New Jersey, when we were shooting “On the Waterfront.” Part of the cast were a crew of regular stevedores, about the toughest bunch of men you can find anywhere. To say they were unimpressed by Marlon is to put it mildly. They figured he was a Hollywood bigshot, and they weren’t going to give him an inch. Marlon spent about three weeks on the docks before the actual filming, going around with them, learning how they worked, sharing their lives as much as possible.

One day he was in the hold of a ship watching them load heavy crates of machinery. A stevedore had been hurt and the gang was temporarily short. “Give us a hand, Marlon,” said Brownie, the gang boss, and handed him the injured man’s hook. It was dangerous work requiring a good deal of experience. Without a word Marlon took hold of the next crate. He probably would have continued working till the noon break if Brownie hadn’t stopped him after a few minutes when the regular replacement was sent down. It was sort of a test. After that he was in.

Later, during the actual shooting, he saw to it that each man in turn got his chance to be in the picture right next to him. In order to tell and show Marlon that they liked him, they invited him to a party at one of their hangouts after the filming was finished. Unfortunately Marlon had to go out to Hollywood for a new assignment immediately and regretfully had to break that date. He left enough money with Brownie, though, to take care of the boys’ gullets and stomach.

Although as the star of the picture he had a chauffeur-driven limousine at his disposal, he preferred riding the Hudson tubes between New York and New Jersey to and from work. He found it saved him time. Since he isn’t fond of getting up before dawn, he saved even further time by traveling in his working clothes—an old, checkered woolen jacket, a greasy tie and rough works pants. It seems none of the commuters ever recognized him that way.

Marlon, however, is invariably kind when people do recognize him and ask for an autograph. I’ve seen him take off his mittens in freezing weather to scrawl his name for some kids, and he must have posed for more Brownie fans than he did for regular studio photographers.

Before Eva Marie Saint was engaged for the lead opposite him, Elia “Gadge” Kazan, our director, introduced her to the cast. It was Eva’s first big break and she probably was a little shy and nervous.

“How do you like her?” Gadge asked Marlon, pulling him aside.

“I think she’s swell,” he answered. “But do you think she likes me?”

“Don’t worry about it,” Kazan smiled.

After that, Marlon made it a point of spending as much time as possible with Eva. They ate lunch together every day, and had long talks whenever possible. Since they had to play love scenes together, he wanted to become really fond of her and get to know her as well as he could. There was never any romance between them—Eva is happily married to Jeff Hayden, a successful young television director—but Marlon needs the glow that comes from sincere friendship and attachment to his leading ladies. As a result he’s made fast friends of both Eva and her husband, Jeff. He was the same way with Kim Hunter in “Streetcar.” They frequently took long walks in the country, which is one of Marlon’s favorite ways of getting to know someone.

Marlon doesn’t care for hunting or fishing, but he loves to be outdoors, roaming the countryside without any special goal or purpose. He doesn’t play golf or tennis either, but he’s real happy when he can flop down in a haystack, chewing a blade of grass and watching the clouds go by.

With all his maturity as an artist—and he is an artist, make no mistake about it, a real artist—he sometimes strikes me as still being a kid underneath it all. Once he made up what looked like a big black tarantula from bits of wool, string, twigs and scotch tape. For more than a week he had a wonderful time dangling it from a string in front of unwary victims. There’s never anything mean in any of his jokes, but he loves that kind of prank. I really think it’s that quality of boyishness in his character that makes him so likeable.

From what he tells me it got him into plenty of trouble, though, when he was in school. To this day you can’t just tell Marlon to do anything. He hates to be pushed around and chafes under any form of rigid discipline. As a boy he seems to have set a minor record for the number of schools from which he was expelled. The last one was Shattuck Military Academy in Minnesota, where he was politely requested to leave just before graduation.

The reason for this request was a bomb of fire crackers he’d placed at the door of one of the tutors’ rooms. He’d devised an ingenious method of setting it off by making a trail of hair lotion back to his room, which acted as a fuse when ignited. He figured it would burn up without a trace, giving him an airtight alibi that he was studying in his room. It burnt all right, but left the floor singed with a dramatic finger of guilt pointing to Marlon.

More than this one, however, he seems to regret an earlier prank which also backfired but for which he was not caught. The school had a bell on its roof, chiming away around the clock at fifteen-minute intervals. Marlon hated this constant reminder of time, of things he had to do or hadn’t done. One night he climbed to the roof, disconnected the clapper and buried it in the ground. The clapper wasn’t found, and since this was during the war and there was a shortage of metals, it couldn’t be replaced. Marlon’s regret springs from the fact that from then on the school used cadet buglers to blast away on the quarter hour. “The chimes,” he says, “at least were melodious.”

Marlon’s quite musical, loves to dance and has a wonderful sense of rhythm. One of his hobbies is playing a set of Afro-Cuban drums. No, I don’t know how his neighbors feel about that.

Another of his hobbies for a while was his big red motorcyle. On the day he bought it I remember asking Jessica Tandy, who played Blanche Dubois opposite him in “Streetcar,” whether he could drive her home after the show. She said she’d be delighted. Jessica is a wonderful girl and a good sport, but she’s also very much the lady. She did a real double-take when he led her to his motorcyle. A cop got her off the hook. He was there, too, writing out a ticket for illegal parking. While Marlon tried to talk him out of it—unsuccessfully, I might add—Jessica hopped into a cab.

With all his playfulness and exuberance, it’s a fact that there’s also a darker, brooding side to his character. I’ve seen him hit by sudden spells of moodiness and when that happens it’s as though a dark shadow were cast over him. I don’t know what eats him when he’s depressed like that, and I suspect he doesn’t know it himself. My guess is that he’s simply a highly intelligent and very complex human being, and I’m satisfied to leave it at that.

Marlon’s very first stage part was as the poet Marchbanks opposite Katharine Cornell’s Candida. It’s funny that ever since he’s been cast as a tough guy, when he’s really one of the kindest and gentlest persons I know. Maybe the inner drive that makes Marlon a great actor is the chance for release on stage and screen, the opportunity to project facets of his personality that he cannot live or even acknowledge in his personal relations. Off-stage, violence or brutality are completely alien to him. I can’t think of anyone who is less of a bully than Marlon, and I don’t imagine it’s merely an accident that his closest personal friend should be Wally Cox of “Mr. Peepers.”

What I like best about Marlon, in fact, is his real concern for the underdog, for the little guy who is liable to get hurt. Once during the shooting of “On the Waterfront,” his stand-in told him that he hadn’t been paid in a couple of weeks and needed the money. Marlon changed character almost before my eyes, and when Mr. Spiegel, the producer, came out to Hoboken next day, I honestly was afraid I’d see Marlon commit mayhem.

“What’s the big idea of not paying Jack promptly?” he demanded furiously. “It’s not one-tenth so important you pay me as it is to pay a guy like Jack who really needs the dough.”

It was also typical that the one time I saw him get tough and badger someone he picked on the boss. I’m sure there was no malice on the part of Mr. Spiegel or anyone else, it was simply an oversight, but Marlon felt there was no excuse for that sort of thing. Incidentally, Marlon’s probably the only actor in history to invent a new way of not getting a job. Once when he was to meet a producer he didn’t like, he greeted him with a fresh-laid egg concealed in the palm of his hand.

Nor—be it said to his credit—is Marlon doing that sort of thing only since he’s become an established star. Eight or nine years ago, when he was still struggling for recognition, his agent sent him to Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne for an audition for a part in one of their productions. He walked up on the stage and was handed a script from which he was to read. Even to this day he hasn’t learned to give a good reading without time to study the script, and on that occasion he was completely tongue-tied.

“Well, say something,” Alfred told him, annoyed. “Say anything you like.” “Hickory-dickory-dock,” Marlon said and walked off the stage.

Needless to say that in the case of his stand-in he immediately helped the boy out by a personal loan. Marlon’s probably the softest touch I know. He’s completely unable to refuse anything to a friend—or to anyone else who’s in need. I know of one mutual actor friend who was down on his luck and was supported by Marlon for close to a year. I know of another case where he did all he could to help a young couple who were friends of his. They were in love, out of work and broke. “Go ahead and get married,” he told them. “Everything will work out all right.” He helped them get jobs and tided them over with money when they needed it.

That kind of generosity is one of the reasons why he always used to be broke. Another is that he simply has no money sense. I once saw him tip a shoeshine boy five dollars. By contrast, you have to watch him like a hawk to keep him from putting the bite on you for an endless supply of quarters and dimes. When he really started making money his father, therefore, suggested to him that he let him handle his finances. Marlon’s entire paycheck is now turned over to his father, who merely gives him an allowance: something like a hundred dollars a week when he often earns ten times that much. As a result Marlon is today probably more secure financially than most other successful young actors. Among other things, he owns a ranch in Nebraska with a herd of a thousand head of cattle. That kind of a backlog gives him the independence he cherishes above all other things.

As I mentioned before Marlon has no taste for luxury except the one of being completely free and unrestricted. He loves to travel and is fiercely jealous of his freedom, resenting bitterly any form of pressure and compulsion. I think, though, he’s a little sorry today that his rebelliousness in school kept him from going to college. He has a great deal of intellectual curiosity, is very articulate and reads constantly to fill in the gaps in his formal education. He can be extremely serious, and I know of no one who works harder at his craft than Marlon. There’s no foolishness about him during rehearsals. He’s always prompt, and I’ve never seen him throw tantrums or become tempermental like a lot of stars.

His childhood, by the way, seems to have been a very happy one, despite his antics. The Brandos are a very closely knit family. He adored his mother and was grief-stricken when she passed away recently. He’s on excellent terms with his father and very close to his two sisters who live in New York, for whom he frequently baby-sits for an evening with his little nieces.

What else do I know about Marlon? As I said, he likes to travel and is especially fond of France, though he doesn’t go in for fancy cooking. When we’ve eaten together in restaurants he’s usually suggested a dairy place, and once or twice we went to the House of Chan for a Chinese dinner. He plays a very good game of chess, but I’ve never seen him play cards or gamble. He likes jazz, bebop and modern dance. When he’s in a play, he keeps in shape by going to Sid Klein’s gym on Broadway to work out with barbells and do mat exercises. He’s also an excellent horseback rider.

To sum it up, I’d say Marlon has a set of standards that may not necessairly jibe with those of a lot of movie people. But plain, ordinary folks never find him hard to take. There’s real substance to him, and I for one consider it a privilege to call him a friend.

THE END

—BY KARL MALDEN as told to Ernst Jacobi

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1954

vorbelutr ioperbir

4 Temmuz 2023Thanks for another great article. Where else could anybody get that type of information in such a perfect way of writing? I have a presentation next week, and I’m on the look for such information.

zoritoler imol

1 Ağustos 2023Hi, Neat post. There is a problem with your website in internet explorer, would test this… IE still is the market leader and a big portion of people will miss your excellent writing because of this problem.