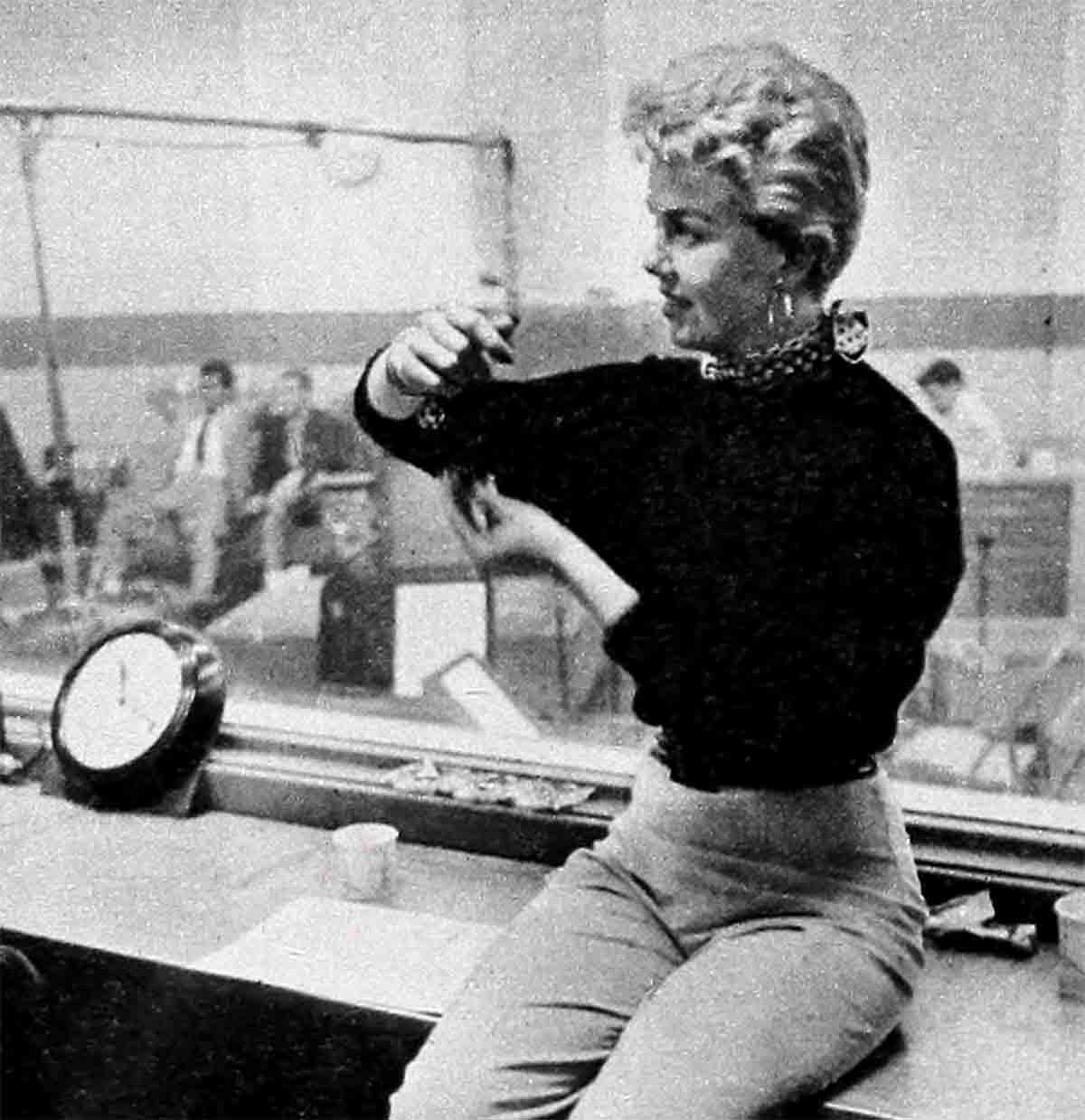

Wake Up And Live!—Doris Day

About the chipperest little character in the movie business is Doris Day, a freckled-faced party who has nothing but the warmest sentiments for the whole universe and who is worth to her employers roughly what oil is to Standard Oil.

It has been reported of Miss Day—and with the greatest affection and respect—that in the past few years she has deliberately and successfully sought a balanced and happy existence built on a strong faith.

“There’s no doubt,” she said recently, “it gets better as it goes along.”

“Life?” I asked.

“Of course,” said Miss D. “I’m happy now, every living day. So how can I help but be happy in the future? I figure that by the time I’m eighty, I’ll hardly be able to stand it. Happiness, I mean. It’s like money in the bank, it adds up with the years!”

Meanwhile, until that long-distant day, Doris Day is the possessor of the nicest working philosophy of the 1954 season, which she expresses very well.

“My. childhood was very happy,” she says. “And don’t think for a moment that I’m compensating for anything. But—this is true, I know it is—life opens up like a flower as you live it. You keep learning and developing and discovering new avenues for happiness. And each year is better than the ones you left behind. All those past years were great—then. But the new ones are greater. And that’s true because you’re older. You see what I mean, don’t you? It follows an interlocking pattern. Life has to be this way, doesn’t it? It’s a logical sequence.”

This kind of optimistic philosophy has been a logical sequence for Doris Day, who happens to be a person of rather extraordinary talent, beauty, courage and faith.

These enviable characteristics helped her to ride triumphantly through a number of crises which might have whipped a lesser person. In her very early teens, she was all but mangled in an automobile accident and spent the next fourteen months in and out of the hospital. An early marriage to a musician named Al Jorden did not succeed, although its precious gift was Doris’s adored twelve-year-old son, Terry. And a second marriage to George Weidler, brother of one-time child star Virginia Weidler, also failed.

It was shortly after this second emotional crash that Doris had a crucial interview with screen director Michael Curtiz. On this interview hinged the decision as to whether she would break into pictures or not. Doris was so upset over her personal life that she was practically in tears. Fortunately, Curtiz was able to perceive the fundamental radiance of the girl and did not reject her.

These events are cited to show that, far from being a vapid Pollyanna, Doris is a woman who won her joy and peace of mind over genuine difficulties. And these events are set down from the record, rather than any direct remarks Doris made to me. Doris Day has no truck whatever with sour notes—a wonderful way to be.

Doris gets fun out of everything. The day I talked with her at the studio she was full of a new enthusiasm. “When I leave here,” she said, “I’m going home and garden like crazy. I’m on a gardening kick you never saw the like of. I love it. But that’s new. Before, I thought gardening was on the square side. But now that I’ve tried it, it’s great. It’s like anything new you learn in life. And that’s what I’m talking about. Life gets better and better the older you get and the more you learn.

“Who’s afraid of growing up? Who wants to go running back to their youth? Fiddle-Faddle. If life were intended to be like that, you might as well crawl into deep freeze when you’re seventeen. But it’s not like that. It’s the opposite, and I wish everyone the same luck finding it out that I had.”

“What’s the opposite?” asked Marty. Marty had arrived. Marty Melcher. He is Miss Day’s agent. He is also her husband. He has a lot to do with the way Doris feels these days—an awful lot. Marty is more the executive type; not as pretty as Mrs. M. but broader through the shoulders. Marty was hungry. He had buffet—part of Miss D.’s plate, part of mine. “What’s opposite?” he repeated.

The life-gets-better-all-the-time theory was explained to him.

“You’re not fooling,” said Marty. “I can hardly wait till I’m ninety. What’s this, salami?”

Mrs. M. ignored him. “Take tonight,” she said. “We’re going out. Company first and then going out. That’s a switch. We’ve been in a rut for a while, sticking close to home. But now we’re mixing around like fury. I’m not exactly the backward type, socially, but I’m slow to make a move. Marty has to push me. But after he pushes me, I’m all the way on the other extreme. Some momentum. For a while there I was one of those worried hostesses. We’d been changing the house around as usual and it doesn’t look too neat, so I was afraid people’d criticize. Well, of course, who cares? I mean, do you care if you go to somebody’s house and it doesn’t look slick as a peeled egg? I don’t. I can’t imagine the two of us driving home from a party saying, ‘Dear, dear, wasn’t the Chumleys’ place a mess!’ So why should anyone think it of my house? Live and learn and stop worrying, I always say.”

“She always says that,” “Take New York.”

“All right,” said Doris. “Take New York. We’re going to New York next week. Super Chief. Razz-mah-tazz. Take the cameras and shoot movies out the window. Go to all the shows and the great restaurants. I used to be a little reserved about that. Maybe I was backward. No more, though.”

“You’re certainly kicking out that old idea that the days of one’s childhood and/or youth are the happiest days of one’s life,” I said.

“The idea’s depressing,” “even if it were true.”

“Which it is not,” said Marty.

“It’s certainly a negative, downbeat sort of attitude toward life,” said Doris.

“It’s worse than that,” said Marty. “Walk up to a kid who’s had a tough day in spelling or been stood in a corner for misconduct and tell him these are the best years of his life. What kind of an outlook are you giving him?”

“And the whole concept is not true,” said Doris, “it’s really not. Sure, childhood’s fine—for childhood. But I don’t want to go back. I wouldn’t go back. And that’s not entirely because of my being in pictures now and having Marty and Terry. The point is that happiness is a gathering process, not something they give you for a little while when you’re young and then take away. I don’t mean you should hurry growing up. Because, for one thing, you can’t. And for another, it’s a mistake. You absolutely can’t be twenty-one until you are twenty-one. But to look back on past years with regret, that I can’t see. Take ‘em as they come and that’s the fullest life there is. Who cares how old you are? I loved being twenty. And twenty-five. I’ll love being thirty-five even more. And forty and fifty!

“The more I know, the more I realize. And the more I realize, the happier I am. That’s not a Pollyanna attitude, the way I look at it. That’s common sense. Every day I wake up proves it to me. I live it. That’s the final answer. You can theorize all you want about many things, but when something happens to you, you know what’s right and wrong for you. Excuse me if I sound like a big wheel, but I know what I’m talking about. And I want everybody else to feel the same. No way to go but up, no way to feel but happier. Anything wrong with that?”

“You’re not depressing me,” said Marty. “Incidentally, how about this childhood bit, anyway? I mean, how about it? Anybody thought of that? Take this, for instance. Did you like oatmeal?”

“Not especially,” said Doris.

“But you had to take it, didn’t you?”

“Sure,” said Doris. “Did you like homework?”

“Did anyone? Does anyone?”

“Not me,” said Doris. “But I did it. And you know something, I don’t have to do it any more. Or if I do have to, it’s the kind of homework that I really like doing now.”

“There you are. Were you ever afraid at school dances that you wouldn’t be cut in on?”

“None of your business,” said Doris. “But all right, yes—I was. And no one can tell me that the fears of youth and the upsets when you’re a child are petty ones. Not then, they’re not. Did you like algebra?”

“Oh, not bad,” said Marty.

“Well, I didn’t. I’m not sure to this day I knew what they were talking about. And now look at me. No algebra.”

Marty laughed. “You’ve convinced me. Now I think your young life was a chamber of horrors.”

“My young life,” said Doris with finality, “was great. All I’m trying to say is this—those good old days weren’t necessarily the best, and I’m afraid the people who believe so may be unhappy. I’ve found out something pretty wonderful and I’m trying to pass it on. That’s all I’m trying to say.”

“I know,” said Marty. “Keep saying it.”

The great young life of Doris Day dates, as you probably know, back to Cincinnati and April 3 of the year 1924, when she was born Doris Kappelhoff. Her father, Mr. Kappelhoff, was an extremely able teacher of organ, piano, violin and voice. With that much musical heritage to go on, Doris, at age twelve, was dancing with one of the stage shows of Fanchon and Marco.

The accident in her teens slowed Doris up for a while. But she wisely used the long convalescent period to study voice. And by and by she was singing the then-popular song “Day After Day” on a Cincinnati radio station. From this song hit Doris chose her professional last name.

She later joined bandleader Barney Rapp as a singer, and from his band moved on to work with Bob Crosby. Fate was still marking time. A three-year engagement with Les Brown’s band, however, culminated with a recording called “Sentimental Journey,” a great success. After that, Destiny really got on the ball. The rest, as the saying goes, is history.

The successful Marty Melchers live today in a fine home in Burbank in the San Fernando Valley, where the lady of the house gardens like mad. She also eats very well indeed and lately has been reading up on the effects of carbohydrates in the diet. She has taken a stand against them. Sometimes the stand works and sometimes it doesn’t. Also, in a land where her fellow-stars will pose slaving over a hot stove at the drop of a flashbulb, Miss Day not only doesn’t like to cook but admits it. She can, you understand, but who wants to? This independent attitude is typical of Doris.

But when anyone comes to her in real need, she’s the first to turn from personal concerns and offer help unselfishly. For example, she recently received a letter from a bedridden child who had read of Miss Day’s own recent setback and requested sympathetic advice. The child got it—in copious and generous amounts. Words like “sick” and “setback” are not a normal part of Doris Day’s language, but do not think this affected her answer to a sick child’s appeal for comforting.

No star is more sought after by the public, press and by her fans than Doris Day. Her response is genuinely her own. What she says is simple, warm and unrehearsed as spring sunshine. And her belief that life should get better as life goes on is devoutly to be admired. And if Doris Day affirms that it is so, then with her it has been so. Besides—is there a better way of living it?

THE END

—BY JOHN MAYNARD

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1954