Give A Man Room To Grow

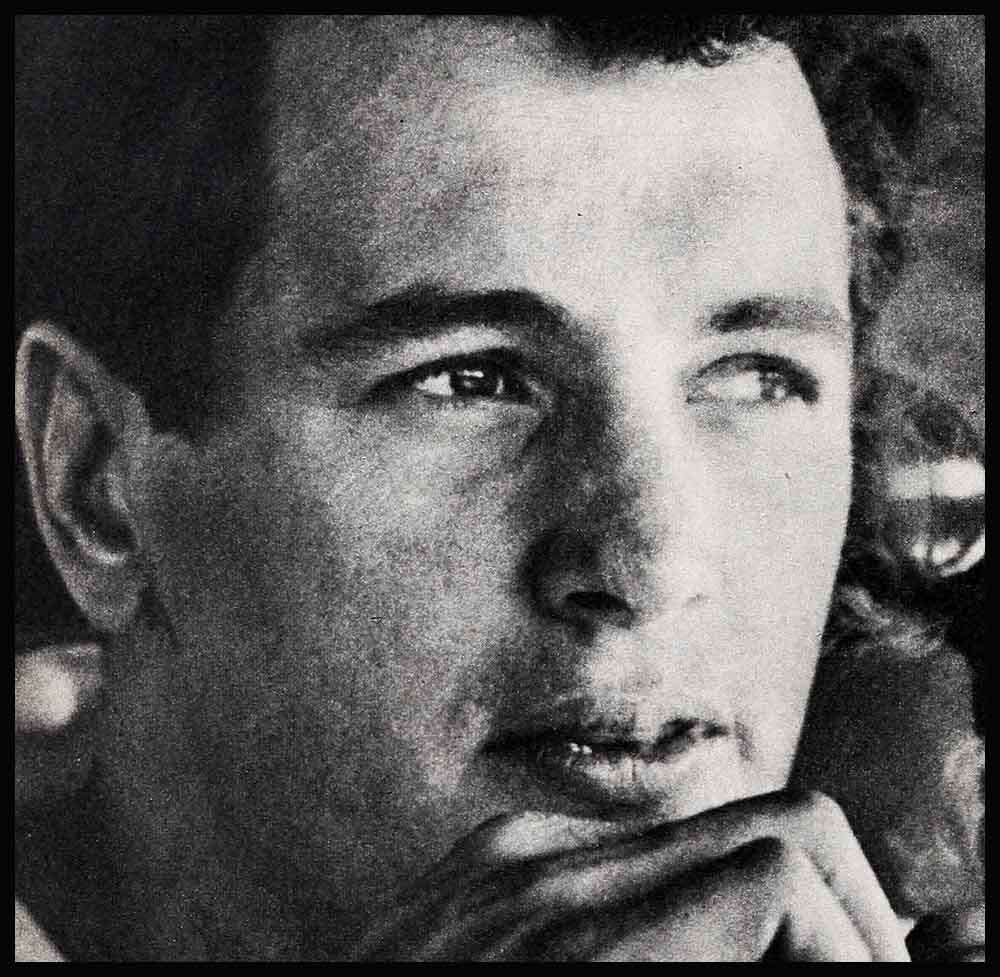

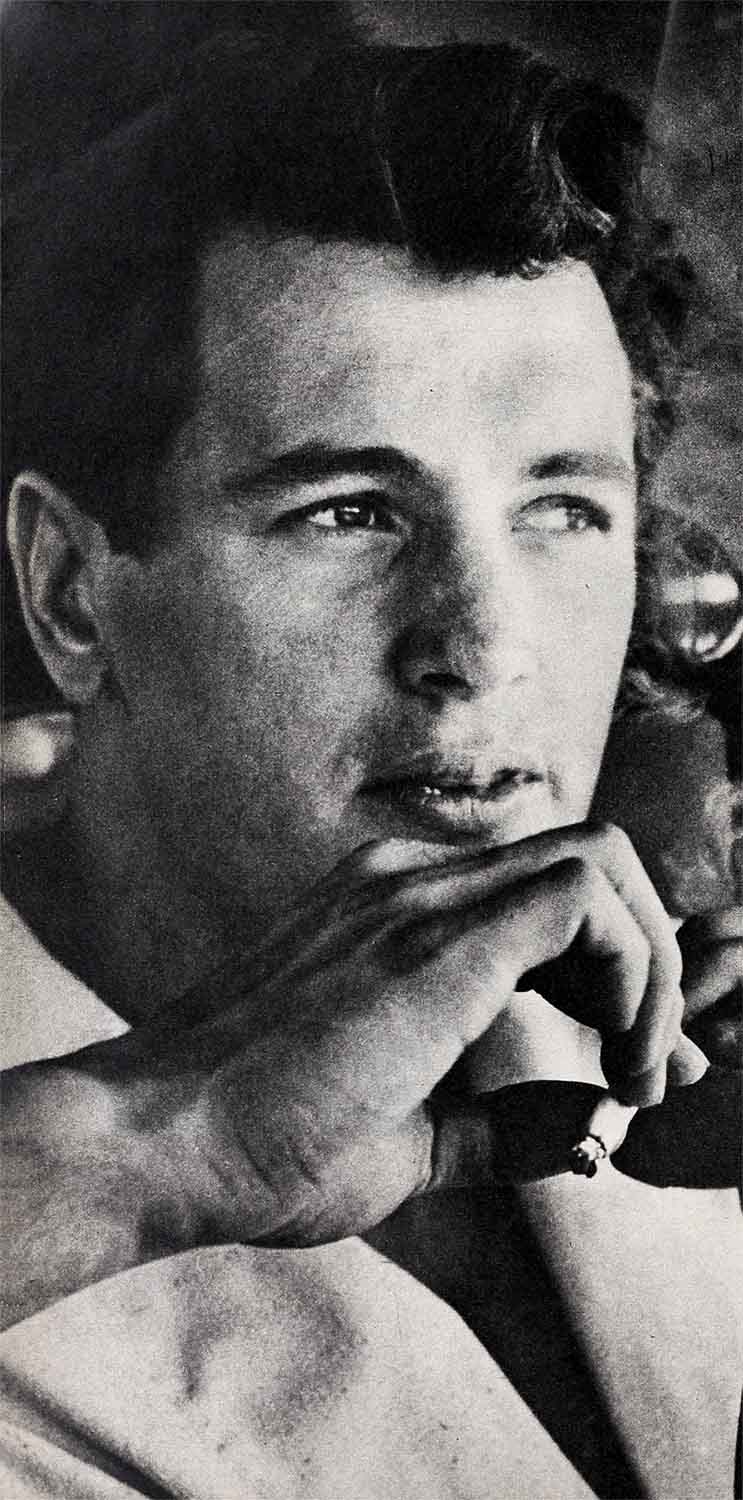

Rock Hudson pushed back his chair and lit a cigarette, sending smoke curling into the air. He had been asked if he considered himself mature, grown up. The question had been tossed at Rock as a kind of teaser to get him to talk. But he was treating it seriously, as if it was something that he was anxious to chat about, to get off his chest. His face grew thoughtful and he seemed to be carefully weighing his answer.

“If you mean in the sense that I’ve stopped growing,” he replied, “or have achieved a State of perfection, I guess I’m not mature. But to me maturity also means getting into a well-worn groove. And I’ve always tried hard to avoid that.”

Rock leaned casually across the lunch table. “I refuse to follow any pattern, or do certain things because other people do them. You know,” he added, half laughing, “I wouldn’t buy a Cadillac even if I could afford one. It’s a great car but there are just too many of them around here. I know that sounds like a kind of inverted snobbishness but the truth is, I just hate to get into line. So I prefer to drive something else.”

Could this account for his not having been married until he was thirty ?

He laughed, his head thrown back. “Maybe it was reluctance. But that’s not exactly fair to Phyllis. The truth of the matter is it just took me a long time to find the right girl.”

Rock won’t discuss his marriage. He feels it’s too precious to talk about casually. But about himself Rock is glad to discuss anything. His own maturity, or lack of it—he’d be glad to talk about that.

“I find that I’m learning to mature by solving my own inadequacies. I guess a lot of people don’t believe it but I fight anxiety all the time.”

How could a man who was as successful as he have anxieties? His personal life, his career, he had them licked.

“That may seem so, but I have to tell you that when the studio, for instance, asks me to go out on a personal-appearance tour, I go into a tailspin. I try to recall all the things I have been taught about speech and diction. Then when I go out on the stage and look into the blurred faces of all those people out front, everything I’ve learned deserts me. I’m literally scared right down to the soles of my feet. I really suffer for the first five minutes. Then I remember to talk simply and directly, kind of visit with my audience, instead of talking at them. Then I’m all right.”

Recently Rock was a guest of Marietta, Ohio, the home of Dean Hess, the flying chaplain, whom he played in “Battle Hymn.” Not only was it a great day for Hess, who was being honored by his fellow citizens, but also for Hudson who received a degree of Doctor of Humanities from Marietta College. It was a memorable moment in Rock’s life. He wore his cap and gown proudly, and he was deeply grateful for the honor that was bestowed upon him. No other personal appearance had made him feel so happy and humble at the same time.

A waitress came over and put some rolls on the table. Rock picked one up and he absently munched on it. He was sort of wound up and he went on as if he wanted to talk it out. “And, you know, it’s the same way when I begin on a new picture. I’m swamped with the same old anxieties, not being good enough, not up to the role I’ve got to play. You should have seen me before I started making ‘Giant’—fingernails chewed to the quick, mouth as dry as a chip. In the first few scenes I worked like a slave with a bullwhip being cracked over him. I was that way until George Stevens, the director, told me to calm down a bit and take it easy. After that things were better. I suppose that’s a kind of growing up—recognizing and overcoming one’s deficiencies.”

Rock took a big bite out of the roll and motioned to the waitress for a menu. He studied it for a long time, asking her if this or that was fattening. At last he settled for a steak, no potatoes or bread. He threw down the roll disgustedly. “I’m the kind of guy who can easily polish off three ordinary meals at one sitting. If I ate the kind of food I love—rich gravies poured over a hill of mashed potatoes, and so on—I’d get really out of condition. I don’t though. You suppose that’s a sign of maturity?”

He polished off his steak, leaned back again in his seat and lit another cigarette. He took a deep drag and then looked up toward the ceiling, silent in thought.

It was easy to understand the remark made by a studio makeup artist after working over Rock’s face. “Hudson’s face is almost too handsome. In most actors you have to take out lines. But with Hudson you have to put them in.”

This aversion to mere good looks could well be Rock’s reason for slouching around in denims, moccasins and a faded sweater, often unshaved.

Rock ground out his cigarette and went back to talking about growing up. “I don’t know whether this is a sign of immaturity or not but my greatest fault is my inability to get sore at the right moment. If someone deliberately insults me—and that has happened a few times—I carry it around in my head, getting madder and madder as I think about it. Finally when I do blow up, I’m likely to lose all sense of dignity and proportion and say and do things I’m sorry about afterward. I guess I’m what they call a ‘slow boil.’ ”

One of the things that does get him “boiled” up is the lack of responsibility many parents show toward their children. He deplores the tendency today, when people have too many material possessions, to give youngsters everything they want. “As a kid,” he said. “I had chores to do every day. As soon as I was big enough I ran a paper route, getting up at five in the morning. And after school I had to high-tail it to the stores for groceries. There wasn’t time for me to experiment with things that would have gotten me into trouble. If I showed any tendencies in those directions, I got a liberal application of old-fashioned strap oil. I’m pretty sure it didn’t do me any harm. And then before I knew it, there was the war. Kids grow up awful fast in the Army or Navy. I was drafted at eighteen and at first I was resentful. After I was in awhile though, I loved it. It was the only university I ever attended.”

He said this neither proudly nor humbly. It was a simple setting forth of facts. One has the feeling that he was a good sailor, going along with conditions as he met them, never pitying himself. His own big hurdle was a native shyness which still troubles him. “I never had the gift of gab,” he said, “so I just shut up, limiting responses to ‘Yes, Sir,’ or ‘No, Sir,’ as the case indicated. For once my total lack of exhibitionism was an asset. The Navy is generally tough on guys who talk too much.”

He went on to talk about kids, the unregenerate young rebels who, too often, end up in a mess of trouble. Rock dislikes the term juvenile delinquent. “Kids, these days, are growing up in a pretty complex world,” he said. “They have nothing to keep them busy, no responsibilities. So being born adventurers, they keep looking for new things to try. But they are not delinquents. If anybody is, it’s their parents. I hope Phyllis and I have a large family—five or six children. And believe me, they’ll get a lot of attention and a lot of love.”

Rock signaled to the waitress for a check, fell back against the cushions of his chair and placed his big hands on the table.

“About this maturity thing again,” he said, getting up to leave, “I wonder if it isn’t just a matter of needing a lot of room to move around in—a chance to stretch out, to test your wings.”

When he stood up his head nearly touched the low ceiling of the restaurant, his shoulders filled the corner where he had been sitting.

Yes, Rock certainly did need a lot of room. But unlike most men, Rock Hudson had the whole world to stretch out and grow up in.

THE END

YOU’LL LOVE: Rock Hudson in U-I’s “Battle Hymn” and M-G-M’s “Something of Value.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MAY 1957

No Comments