What Really Killed Marilyn Monroe?

The ‘Love Goddess’ who never found any love

Early on Sunday morning, Aug. 5, 1962, Marilyn Monroe died by her own hand. The suicide of this radiant woman, “The Love Goddess of the Nuclear Age,” was splashed across the front pages of the world and produced an orgy of public commentary. Editorialists, political commentators, creative writers, dramatic and literary critics, fellow artists, friends and foes seemed obsessed by the question of why this woman, possessing beauty, fame and money in such abundance, had so feared or hated life that she could no longer face it.

She was identified as an innocent victim. It was widely felt that somehow she had been condemned and driven to her death as surely as any hapless aristocrat condemned by the tribunal of the French Revolution was driven in the tumbrels to the guillotine. And in the days following her death, the sob sisters and gossip writers gave a fine imitation of the Old Ladies of the Guillotine who. gleefully knitted while counting every head that fell into the basket. But although views differed as to who or what had condemned and finally executed her, Hollywood was far and away the most favored villain.

In Moscow, Izvestia commented that Hollywood “gave birth to her, and it killed her.” The New York Daily Worker indicted the capitalistic motion picture producers who “turn woman into a piece of meat,” and sell not only the bodies but the “souls of their fellow human beings.” The Vatican’s L’Osservatore Romano put the blame on the general decline of morals, holding that Marilyn was the victim of a godless way of life of which Hollywood “forced her to be the symbol.” Britain’s Manchester Guardian saw her as the victim of her fans, forever haunted by “a nightmare of herself 60 feet tall and naked before the howling mob.” The New York Times blamed the Hollywood star-system. “The sad and ironic realization,” said the Times, “is that Miss Monroe aspired to creativity. . . . But the effort to overcome the many obstacles . . . was apparently too great for her. Therein lies her tragedy and Hollywood’s.”

On the second anniversary of Marilyn Monroe’s death perhaps what most wants saying is that whoever or whatever killed Marilyn it was not Hollywood. The easy acceptance of Hollywood as the author of her tragedy has obscured whatever meaning and moral her life and death may have for the public.

Hollywood brought Marilyn Monroe fame, money, adulation, two respected and also famous husbands (Joe DiMaggio and Arthur Miller), and the help, however belatedly sought, of competent psychiatrists. But for all these, Marilyn might have gone to her death in her twenties instead of her thirties.

Indeed, the “howling mob” who made her see herself as “60 feet tall and naked” gave her the only form of sustained emotional security she ever knew, or perhaps was capable of understanding. For if her public saw her as a “Love Goddess” to whom limitless love was owed, that is the way she saw herself in her happiest hours—most of them Hollywood hours.

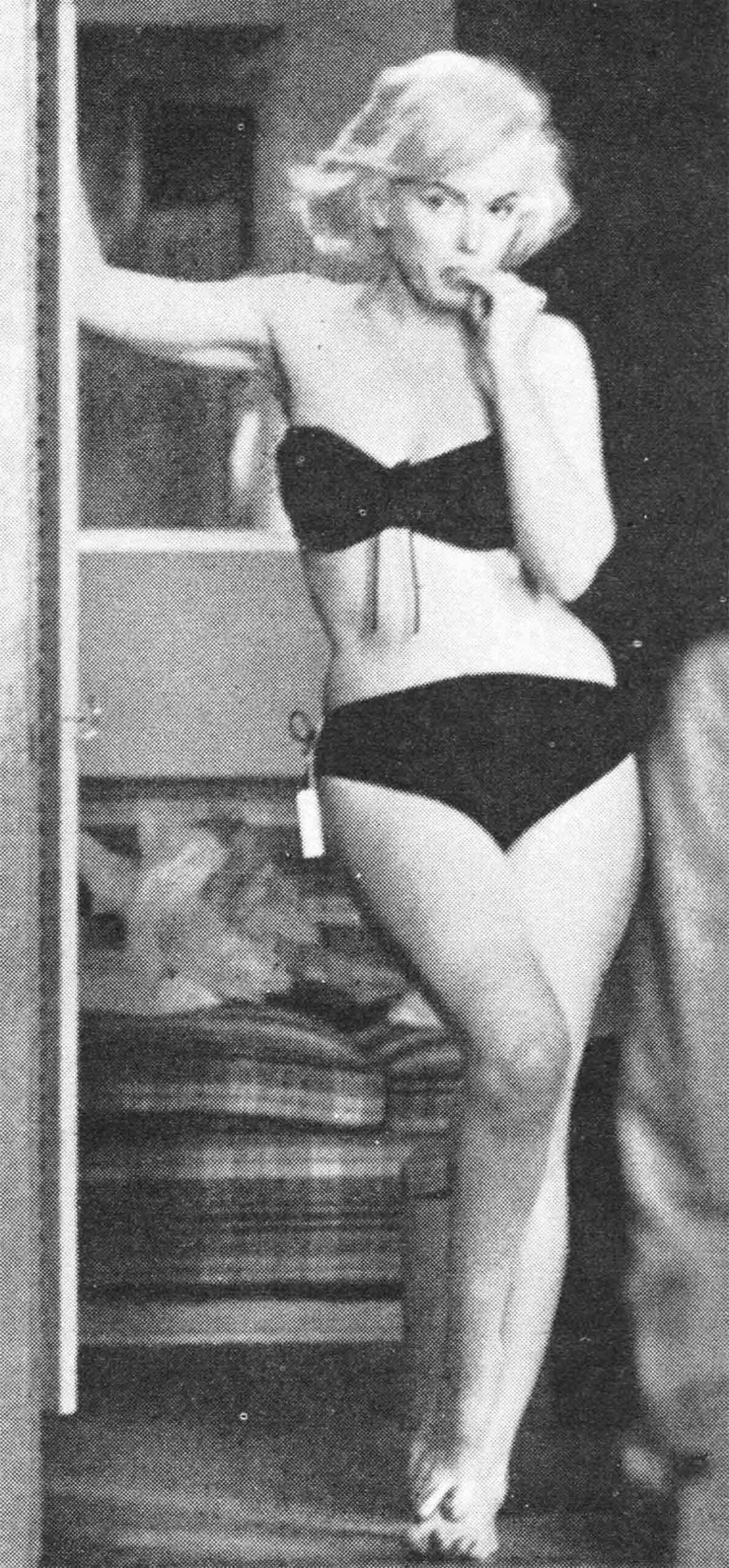

A few weeks before she died Marilyn told Life: “I think that sexuality is only attractive when it’s natural. . . . We are all born sexual creatures, thank God, but it’s a pity so many people despise and crush this natural gift. Art, real art, comes from it—everything. I never understood it—this sex symbol—I always thought symbols were those things you clash together! That’s the trouble, a sex symbol becomes a thing—I just hate to be a thing. But if I’m going to be a symbol of something, I’d rather have it sex . . .”

At the conscious level, Marilyn believed that her extraordinary power to project sex was her great gift. Her despair at the end was perhaps akin to that of a painter who discovers he is going blind, or of a pianist whose hands are becoming arthritic. The threatened loss of a great talent or functional capacity which a person sees as the paramount meaning of his life—the “reason why” of his being—has often led to a suicide.

Whatever else Marilyn had hoped—and failed—to find in life, her “howling” public must have been what she most feared to lose when she reached out for her last and lethal dose of barbiturates. Surely she realized that the mob worship of her for her pure sexuality could not last more than a few years longer. Breasts, belly, bottom must one day sag. She was 36, and her mirror had begun to warn her.

A girl entering her teens, especially an American girl, has intense, secret, often lengthy encounters with a looking glass. They are a legitimate manifestation of every unmarried girl’s concern for her future as wife and mother. She learns early that the male has a natural preference for young and pretty women. But too often she continues, even after marriage and motherhood, to believe that who she is is what she looks like in her mirror. Advertising spends billions of dollars fostering this essentially immature attitude in adult women. For, the more mature and emotionally secure a woman becomes, the less she turns to the looking glass to give her self-confidence and a sense of her own personhood, and the more she looks into the eyes of the people she loves and who love her for the true reflection of her identity.

But the narcissistic approach to a mirror is a continuing, ever more urgent professional necessity for a movie star who is celebrated, rewarded and adored for her physical attractions. Her daily, often hourly encounters with her “mirror, mirror on the wall,” however satisfying and reassuring in the beginning, become summit meetings with her archenemy—time.

After Marilyn passed 30, her sessions with her studio mirror must have been increasingly agonizing experiences. The growing hostility and aggressiveness she began to show in her later years, especially to men who worked with her, and the endless changes of clothes and protracted primpings in her dressing room, the fits of vomiting just before the cameras began to grind—all these may have foreshadowed her terror of that hour when her multiple lover, the wolf-whistling mobs of men and oohing and aahing women would desert her.

What, then, would make her valuable, even in her own eyes? Who was Marilyn Monroe if not that lovely girl on the screen, that delectable creature she saw in the mirror?

“Everything is so wonderful—people are so kind,” she once said in one of her triumphant hours. “But I feel as though it’s all happening to someone right next to me. I’m close—I can feel it, I can hear it, but it isn’t really me.”

Marilyn knew who the “real me” was. But this was an admission she sought to escape. Her efforts to become a dramatic actress, to interest herself in literature and music, the pathetic efforts she made to adopt the religion of her third husband, Arthur Miller, and to transform herself into his intellectual companion and a good little housewife were certainly a part of her valiant effort to escape this “real me”—who was one of the saddest and most frightened little girls ever born—Norma Jeane Mortenson.

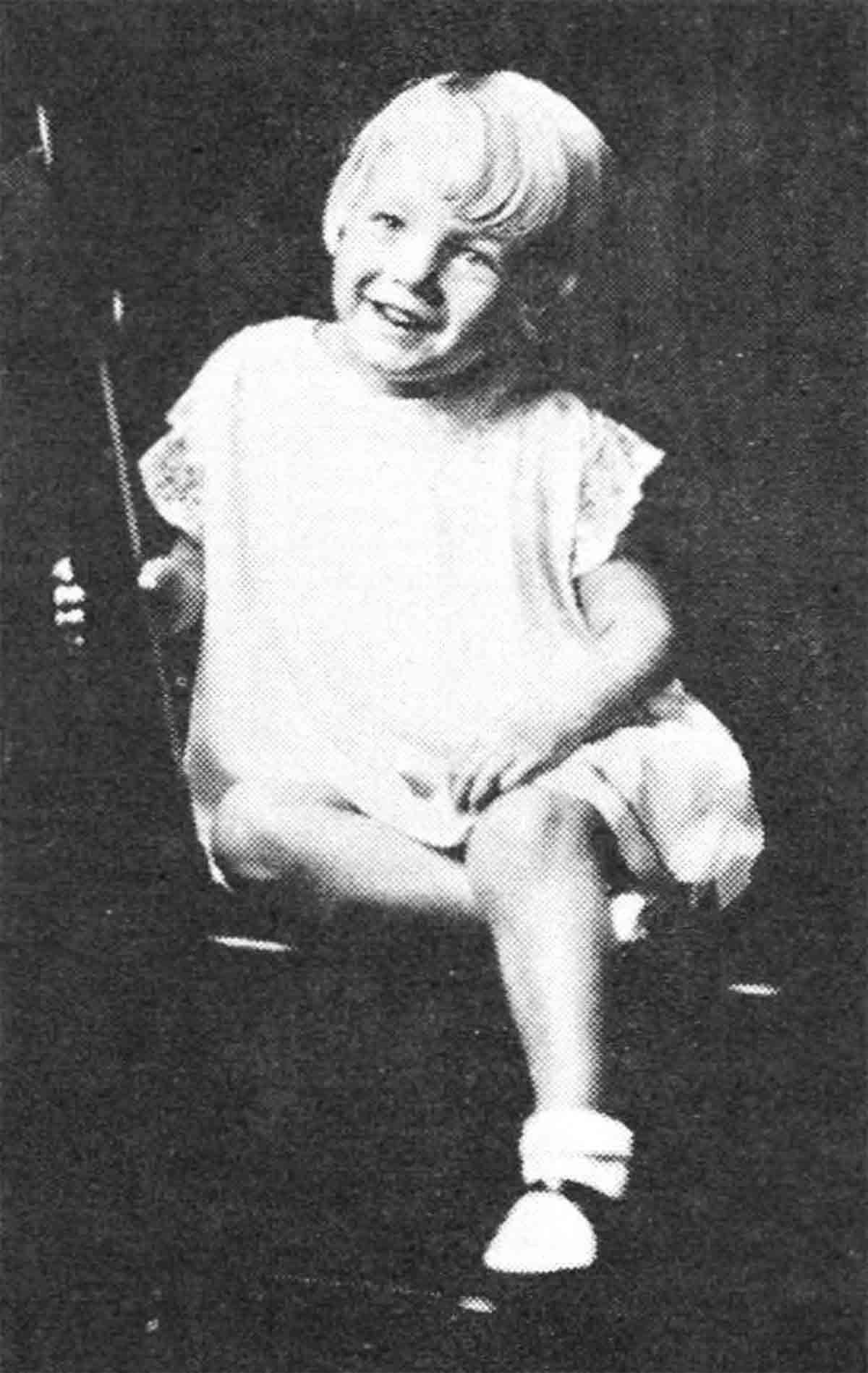

Marilyn’s fate, like her body, began to take shape while she still lay in her mother’s womb. But unlike her body, the shape it took from the beginning was not lovely. An ugly congeries of evil fairies—insanity, illegitimacy, infidelity, promiscuity, ignorance and poverty—presided over her cradle.

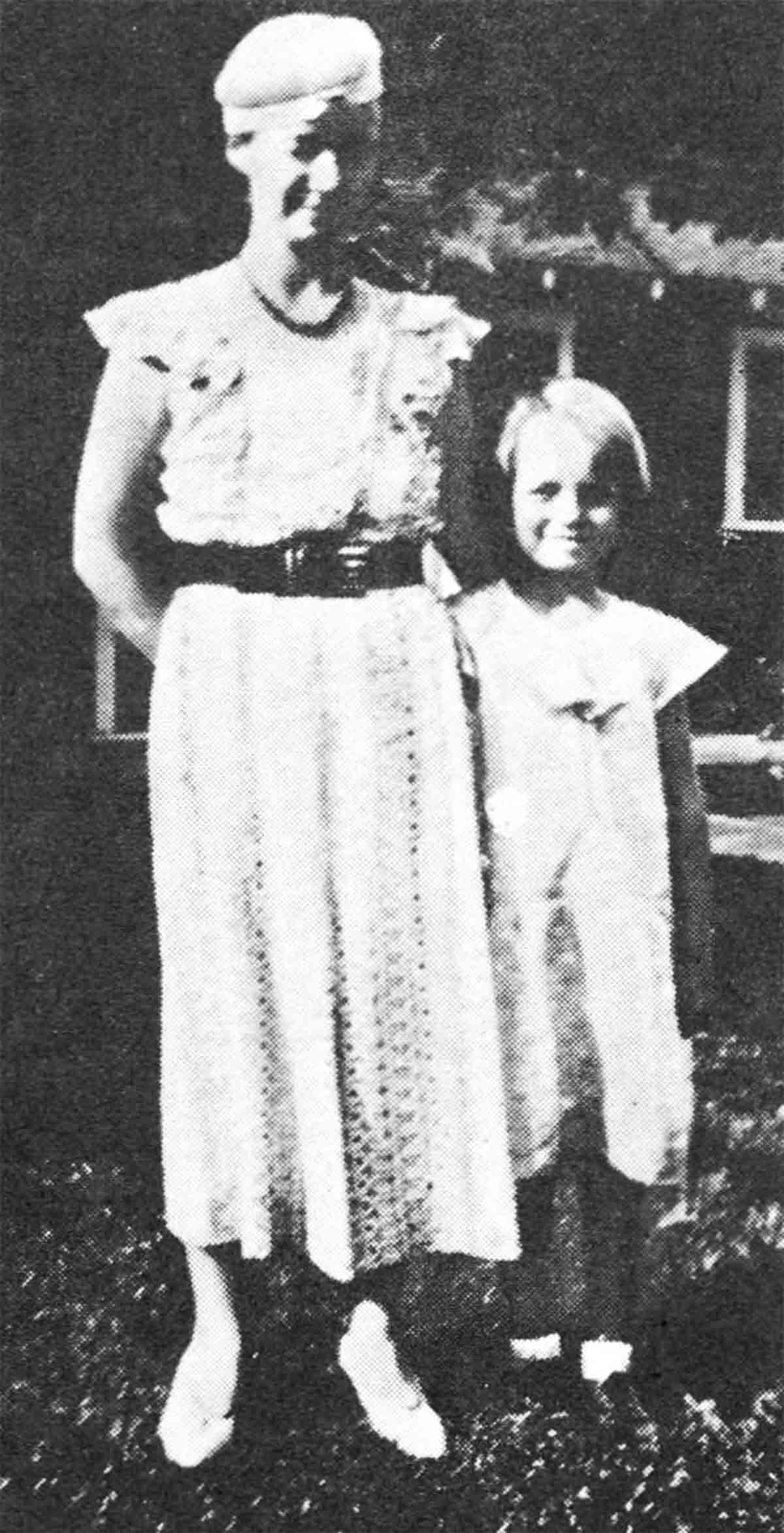

Her mother, Mrs. Gladys Baker, was a pretty, red-haired 24-year-old woman who worked as a film cutter for RKO. Mrs. Baker’s father and mother had been in mental institutions and a brother had committed suicide. She had married Baker when she was 15, and borne him two children. He deserted her a few years later, taking his children with him. A succession of men followed him in Mrs. Baker’s bed, including one Edward Mortenson. The child of this casual union was born on June 1, 1926, in Los Angeles, and baptized Norma Jeane Mortenson. The father was not present: he disappeared, and forever, the day Gladys Baker told him she was pregnant.

Throughout her life Marilyn Monroe was haunted by the enigma of her paternity. Of all the stories Marilyn ever told about herself, perhaps the most touching concerned what happened when she met President Kennedy at his 1962 birthday rally in Madison Square Garden, where she had been invited to sing “Happy Birthday.” Afterwards she proudly attended the reception with Arthur Miller’s 77year-old father, Isidore Miller. “I think I did something wrong when I met the President,” she said. “Instead of saying, ‘How do you do,’ I just said, ‘This is my former father-in-law, Isidore Miller.’ ” Marilyn then explained that she had presented her former husband’s father to the President because he was an “immigrant” and “I thought this would be one of the biggest things in his life. . . .” The chances are it was the biggest thing in Marilyn’s life to say the word “father” to the President, even though her father was an ex-in-law.

Following the birth of her child, Gladys Baker returned to her job. In her moody and feckless fashion, she cared for Norma Jeane during the first few years of her infancy. Then she began to give evidence of violent mental disturbance and was committed to an institution. Norma Jeane was made a ward of the County of Los Angeles. For the next four or five years she was farmed out by the County Welfare Agency to a series of foster parents, who were paid $20 a month. None of her foster homes apparently offered her even the barest security, much less love. The pattern of anxiety, hostility and moral confusion that underlay all Marilyn’s human relations in later life was indelibly set in these early childhood years.

“I always felt insecure and in the way,” she once said, “but most of all I felt scared. . . . I guess I wanted love more than anything in the world.”

At the age of 7 or 8, in one of these “homes,” Norma Jeane was seduced by an elderly star boarder. She recalled in later years that he was an old man who wore a heavy golden watch chain over the wide expanse of his vest, and that he gave her a nickel “not to tell.” When she nevertheless did tell, the woman who was her foster mother at the time severely punished her for making up lies about the “fine man.” The unhealthy and confused emotional correlations she made all through her life among sex, money and guilt may have stemmed in part from this ugly first encounter with man’s lust. After the punishment she suffered for the rape of her innocence, she acquired a stammer which remained with her throughout her life.

Mother Gladys Baker was released from the asylum when Norma Jeane was 8, got a job and took her daughter back to live with her. But a year later she became violent again and was recommitted. Since then, except for brief periods, Mrs. Baker’s pitiful life has been spent in mental institutions.

At the age of 9 Norma Jeane was sent to an orphanage. There she earned nickels by washing dishes and cleaning toilets. The fairy tale Cinderella, sweeping ashes from the hearth, lived a normal, protected, happy life compared with that of this rootless little orphan of the City of the Angels. When Norma Jeane was 11, an old friend of her mother, Grace McKee Goddard, rescued her from the orphanage. Mrs. Goddard sent her to live with her aunt, Miss Ana Lower, in Sawtelle, a Los Angeles slum, and later took her in herself. This was about the only period in all her youth when she knew even a semblance of security and affection.

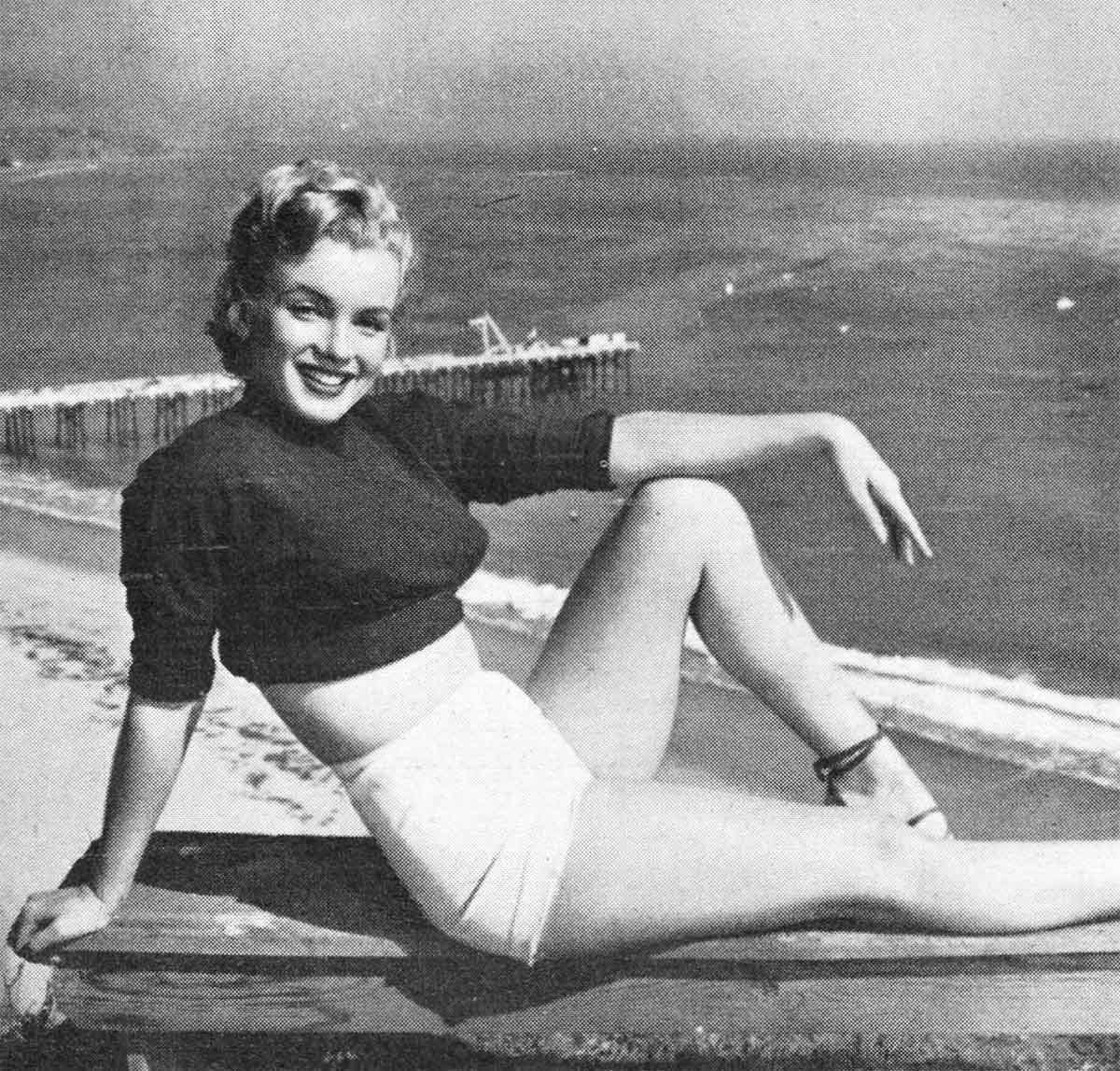

In those years Norma Jeane, like millions of other small girls, also dreamed of becoming a movie star. But Norma Jeane had a special gift. It began to manifest itself when she was 12. One morning, before going to school, she decided to put on lipstick, eyebrow pencil and a borrowed blue sweater one size too small for her. “My arrival in school started everybody buzzing,” she recalled. “The boys began screaming and groaning. . . . Even the girls paid a little attention to me.” Norma Jeane discovered, to her great delight, the one dazzling gift that had been bestowed on her at birth—an exuberant, vital, almost atomic capacity to project her sexuality. Marilyn Monroe was in the making.

She married for the first time in 1942, when she was barely 16. Her husband, James Dougherty, then 21, seems to have been an ordinary “decent Joe.” (He is now on the Los Angeles police force.) In later years he recalled that she was a good cook, but she did not give him the feeling of self-esteem and self-confidence a man needs to keep even a sexual liaison going, no less a marriage. James Dougherty and Norma Jeane separated in 1944, apparently without tears. When he shipped overseas to serve in the Merchant Marine, she obtained a divorce in Las Vegas and went to work as a paint sprayer in a Los Angeles defense plant.

What Marilyn’s sex life was like in the days before she sought to storm the golden gates of Hollywood can only be surmised. It cannot, even by today’s easy standards, have been “moral.” For she had no father or mother image to guide her as to the proper behavior of boys and girls. Never having known the face of marital or parental or even fraternal love, she was certainly incapable of giving what she herself had never known.

In a posthumously published interview, which took place during the first year of her marriage to Arthur Miller, Marilyn offered this explanation: “I guess I was soured on marriage because all I knew was men who swore at their wives, and fathers who never played with their kids. The husbands I remember from my childhood got drunk regularly, and the wives were always drab women who never had a chance to dress or make up or be taken anywhere to have fun. I grew up thinking, ‘If this is marriage, who needs it?’ ”

In the same interview Marilyn said, “Gee, I love being married [to Arthur Miller]! All my life I’ve been alone. Now for the first time, the really first time, I feel I’m not alone any more. For the first time I have a feeling of being sheltered. It’s as if I have come in out of the cold. . . . There’s a feeling of being together—a warmth and tenderness. I don’t mean a display of affection or anything like that. I mean just being together.”

This, of course, was not a mature woman speaking of deep intellectual and physical union in marriage. It was the orphan child speaking—the child who was still seeking a permanent home where warmth and tenderness would always be given unconditionally by the “grown-ups,” in this case by Arthur Miller.

The young Norma Jeane was also always trying to avoid the cold. Despising marriage, deeply distrustful of both men and women but nevertheless hungry to the core of her being for admiration, affection and acceptance as a person, she sought “love” with what must have been a fever-pitch promiscuity. Indeed, by the time she was entering womanhood a miracle was needed to save her from a life of overt or covert prostitution. That miracle happened. Its name was Hollywood.

In 1945 she found employment with The Blue Books Model Agency in Los Angeles as a photographers’ model. The agency advised her to dye her dark blonde hair a golden blonde. Within a year her face, ringed with golden curls—and great peachy reaches of her body—had become familiar and welcome items in all the men’s magazines from Laff to Pic. Soon a screen test was arranged for her and she was signed by 20th Century-Fox. Cameraman Leon Shamroy reminisced some years later that “every frame of the test radiated sex.” These pristine radiations of a Love Goddess did not, however, reach the public. After playing a bit part in Scudda Hoo! Scudda Hay!, which some latterday Gladys Baker left on the cutting-room floor, she was dropped by Fox. The only professional step forward she seems to have made in her 20th year was a second change of name. Norma Jeane Mortenson Baker Dougherty became Marilyn Monroe.

When she was 22 she got an assignment from Columbia, the lead in an obscure B picture, called Ladies of the Chorus, which was shot in 11 days. And it was during this time that the movie magazines first recorded a Marilyn Monroe “romance,” with Fred Karger, a musical director. But the end to this romance revealed, for the first time, that she was already flirting with another escort—death. After the romance failed she made her first of several attempts at suicide. The rejection of her physical person could not have failed to trigger and intensify the feelings of non-belongingness, unworthiness and unwantedness ingrained in her by her miserable childhood.

Marilyn’s first big movie break came when Arthur Hornblow Jr. and John Huston were trying to cast the minor role of Louis Calhern’s mistress in The Asphalt Jungle. It called for an angel-faced blonde with a wickedly curvaceous figure. Marilyn was tested for the part, and Hornblow recalls that she arrived on the set ‘“‘scared half to death’’ and dressed as “a cheap tart.”

“As soon as we saw her we knew she was the one,” he said, but “we had to strip that all the way down to get to the basic girl, the real quality, the true Lolita quality.” This time Hollywood was not looking for mere “meat”; it was looking for the quality that would at once touch the heart, evoking tenderness, and race the blood. This was the quality of innocent depravity and it can be found only in a female “juvenile delinquent.” Marilyn had that quality. Hollywood simply recognized it.

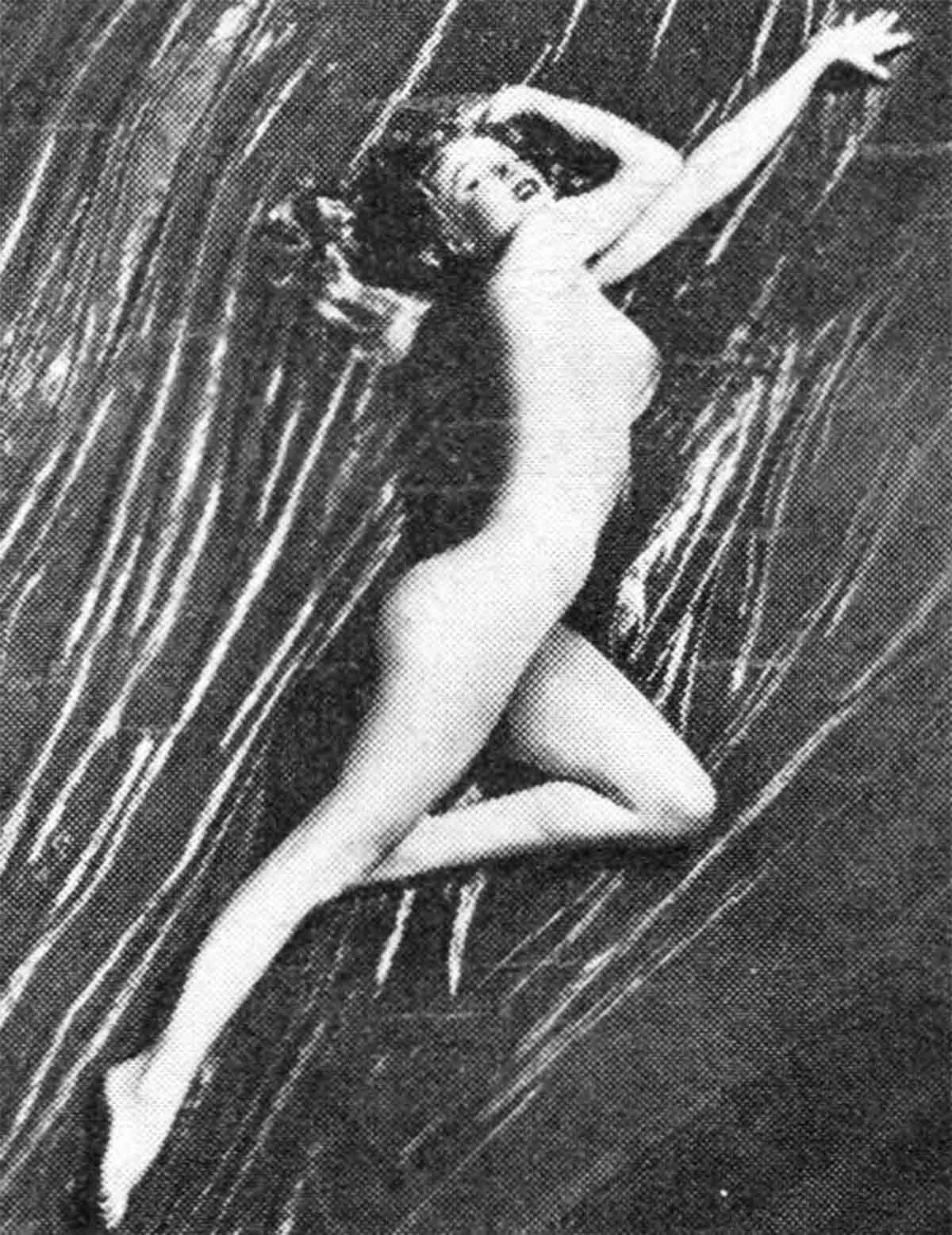

Her part in The Asphalt Jungle got her movie career onto the ways. But again, to exculpate Hollywood of forcing her to become a sex symbol, it should be remembered the picture that first made her famous had nothing to do with the movies. It was a photograph of Marilyn in the nude, for which she had cheerfully posed when she was modeling, a year before she appeared in The Asphalt Jungle. Asked, years after the shot had been circulated worldwide, what she had on when she posed for it, she replied, “The radio.”

The photographer paid Marilyn $50 for posing, sold the picture for $500 to John Baumgarth, publisher of calendars, who reputedly made $750,000 out of it. (The nickel rate established by the Star Boarder was maintained throughout her life. Her sex appeal, which grossed over $100 million for Hollywood, left her with about $500,000 when she died.) This unidentified photograph, which Mr. Baumgarth prophetically called “Golden Dreams,” was a best-seller. The public became aware of the fact that Marilyn was the calendar girl just as her film, Clash by Night, was about to be released. The Fox brass blew their tops and threatened to drop her. Facing again the old foster parent-star boarder pattern of rejection and punishment for a misdemeanor involving sex, Marilyn once more talked of suicide. But this time the “howling mob” and the conquering wolf-whistle came to her rescue. After seeing “Golden Dreams” the public clamored to see still more of Marilyn’s charms—even though there weren’t, really, any more to be seen. Thus, she and the public, not Hollywood, launched her career as a Love Goddess.

Year later she said, “When I was a little girl, maybe 6 or 7, I dreamed of standing up in church without any clothes on, naked and with no sense of sin.” Her rationalization of this dream was that she probably “wanted to take my clothes off because I was ashamed of them. They were orphan’s clothes. Naked, I was like any other girl.” The point was—and “Golden Dreams” made it—that naked, Marilyn was not like any other girl. In terms of nakedness alone she was sheer female perfection, and she knew it and rejoiced init. “Men,” she once said happily, “feel as if they want to spend all night with me!” That the desire to spend all night with her was different from the desire to spend a lifetime with her, she never, perhaps, quite understood—even after the collapse of her three marriages.

The story of Marilyn’s years of stardom as the Love Goddess are too well known to need repeating. But behind the facade of the gay and happy star, this “basic girl,” the tragic Lolita, remained unchanged and unchangeable.

A year and a half after Marilyn’s suicide, the question of “Who killed our Marilyn?” was unexpectedly revived by a competent witness—her third husband, Playwright Arthur Miller. In his autobiographical and self-defensive play, After the Fall, produced last January, Miller, not surprisingly, finds that whoever else was “responsible” for Marilyn’s death, it certainly was not Arthur Miller. But neither does Miller blame Hollywood. He holds that Marilyn wrought her own destruction by insisting on seeing herself as the utterly helpless victim of her parents, her lovers and husbands, her profession and her friends—a victim who, in her own eyes, could be “saved” only by a “limitless love.” Miller’s gloss on this—and one of the themes of his play—is that while every man is his brother’s (and sister’s) keeper, no man could give “limitless love” even to the loveliest and neediest of women. Especially not Arthur Miller who, as the play demonstrates, has quite a few problems of his own in the love-unlimited department.

There is no reason to dispute Miller’s self-exculpation for the tragedy of the woman he brought to bed as his wife for four troubled years and to whom he sincerely tried to give enough of his mind and heart to make any normal woman feel “sheltered.” If, at first, he saw himself somewhat egotistically in relationship to her as a combination of Romeo, Pygmalion and Dr. Freud, this mistake was probably born of the same basically idealistic impulses that led him in his early days to flirt with Communism. To his credit, he recognized fairly early the fatuousness of his attempt to play “Savior” to Marilyn’s ambivalent “Magdalene.” He encouraged her to seek psychiatric help and to bolster her self-esteem by developing whatever gifts she believed she might have as an actress.

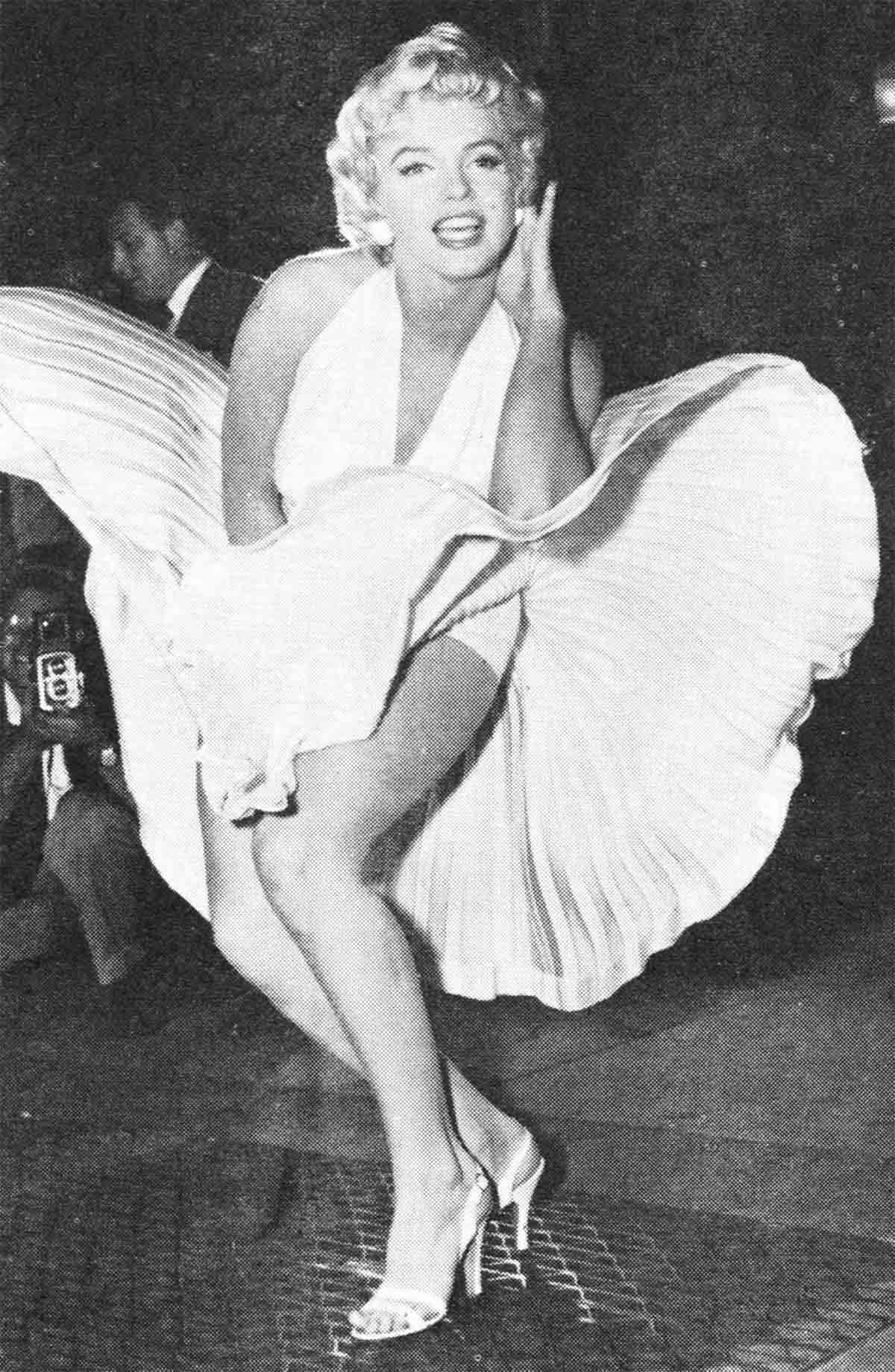

Hollywood’s reactions to Marilyn’s latter-day dramatic aspirations were cruel. One producer voiced this judgment on her dramatic chances: “Act? That blonde can’t act her way out of a Whirlpool bra!” And Billy Wilder, who was her director in The Seven Year Itch and Some Like It Hot, and one of the few in Hollywood she respected, was quoted: “The question is whether Marilyn is a person at all, or one of the greatest DuPont products ever invented. She has breasts like granite, and a brain like Swiss cheese, full of holes. . . . The charm of her is her two left feet.” Asked if he wanted to direct a third film with her, he said, “I am too old and too rich to go through this again.”

Perhaps these judgments on Marilyn’s dramatic talents were as false as they were harsh. But it was true that Marilyn did not have the self-control or self-discipline to become a Broadway dramatic star.

Arthur Miller has accurately identified some of the causes that led to her three divorces, her many troubles with her studio and eventually to her suicide: the insatiable demands for “limitless love,” the moodiness and depressions, the orgies of self-recrimination alternated with orgies of recrimination of others, the clearly self-destructive urges, which were always boiling and seething under the bubbling, slapdash mask of careless, vibrant, even rapturous happiness she tried to project to the public.

Marilyn died, really, on a Saturday night. The girl whose translucent beauty had made her the “love object” of millions of males had no date that evening.

Apparently none of the men or women she knew well had, in the end, cared enough for her to “hang around” and try to cheer her up, although everyone knew she was suffering, physically and mentally. And Marilyn evidently neither loved nor trusted anyone enough to seek help.

Above all, Marilyn was profoundly suspicious of the motives of everyone in her own regard. It was why she walked like a cat, alone, in the midnight alleys of her soul, rejecting lovers and friends before they could get around—as her mother and all her foster parents had done—to rejecting her. She had an almost psychopathic fear of being “used,” financially used as she had first been used by the foster parents who tolerated her only because she brought in her $20 board money; sexually used, as she was used by the man who gave her a nickel for the first display of her sex; professionally used, as in the nature of their business, by producers and agents. No doubt she convinced herself that she had been “used” by her two famous husbands. The egos of Joe DiMaggio and Arthur Miller may have been flattered by their public possession of America’s Love Goddess, but they certainly were not fattened. There is little question but that both men gave her more love, tenderness and understanding than they received. When she died she set up a $100,000 trust fund for her mother. But she left the bulk of her estate to her dramatic coach, Lee Strasberg, and to Marianne Kris, one of her psychiatrists. She must have seen them as the only people who had earnestly sought to help her escape from Norma Jeane Mortenson and find a new identity when her Love Goddess days would be over.

It is interesting to reflect what Marilyn Monroe might think of After the Fall. Morbidly sensitive to exploitation, she would probably be cruelly hurt that her own husband (once a passionately dedicated critic of Hollywood’s “values”) had gone into the business of selling her, body and soul, to the public—and as badly damaged sexy goods. But certainly she would be pleased to find that her “image” still packed a punch with the public. Pathetically eager at the end to be taken “seriously” on Broadway, she would be proud to find her “image” seriously presented in a dramatic work of some intellectual distinction. Perhaps the fact that her former husband had achieved his success—after a long period of artistic impotence—by “using” her would, even while hurting her, please her. It might give her that ambivalent sense of superiority which people often experience when they can feel that someone they have looked up to or trusted has let them down.

In the play Miller makes her say, “I’m a joke that brings in money.” Marilyn would consider it the cream of the jest that, even after her death, the joke is still a big money-maker. For when Hollywood is done with After the Fall, Marilyn’s ghostly ears will once again hear the music she loved best—the loud, lusty masculine wolf whistles of her adoring public.

It was not the scope of Miller’s play, and it is not the scope of this article, to define where Marilyn Monroe’s tragedy, in the words of Moscow’s Izvestia, “transcended personal limits and had social reverberations.” But of course there were instant—and tragic—reverberations to it. The suicide rate in Los Angeles County jumped 40% during the three weeks of “hot” publicity given her death. Those suicides who identified with her may have felt “doomed,” as she felt herself to be, to a suicidal solution of their problems. Others, depressed over their lack of money, fame, youth or sex, may have asked themselves, “If she, the woman who had ‘everything’ had nothing to live for, what do I, with so much less, have to live for?”

For all its “corn,” the simplest lesson of Marilyn’s life is that children need parents, or parent substitutes, who not only love them but who love and respect one another. Without this greatest of all cradle gifts, a happy home, it is all but impossible for them in adulthood to deal with either of those two impostors—failure or success.

Cinderella lives happily ever after only in the fairy tale. In real life, no matter how many clothes she puts on—or takes off—her heart remains embittered and her spirit soiled by the ashes she swept in childhood.

THE END

—BY CLARE BOOTHE LUCE

It is a quote. LIFE MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1964

No Comments