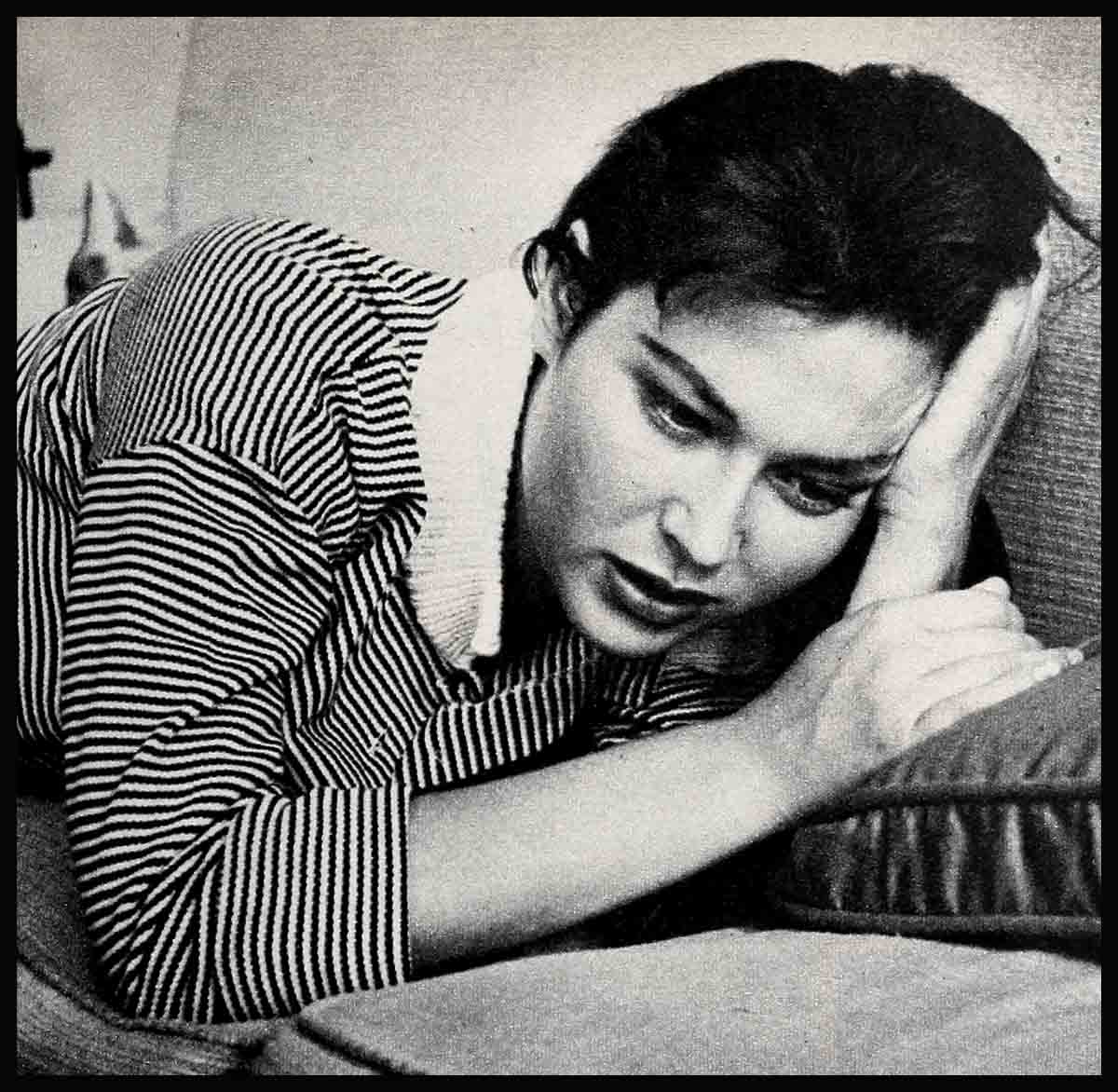

Gia Scala Tries To Take Her Own Life

The cool mist rolled gently across London, covering its streets and buildings with a gray, wet veil. It was late at night and very few lights shone through the thick darkness—but the town was alive . . . you could almost hear its muffled breathing.

High above the streets, in one of the post-war apartments, Gia Scala lay across her bed, her face buried in her arms, one cheek resting against the soft chenille bedspread. Suddenly the phone rang. Gia reached out immediately, before it could ring a second time. She had been crying.

“Miss Scala speaking. Yes, operator. I did. To Hollywood. That’s correct. Mr. Dore Freeman, Hollywood, California. Yes. Thank you. Dore? Dore?”

“Yes, honey. It’s me. Anything wrong?”

“Nothing’s wrong,” Gia answered, suddenly making her voice seem gay. “I’m fine . . . just fine.”

“That’s good,” came Dore’s voice. “How’s London? And how’s the picture?”

“Foggy and pretty good,” Gia said. “And Hollywood?”

“Sunny and what can happen at M-G-M’s still department that would make news?” He was silent for a moment, then he added, “We miss you.”

“Dore, I called to ask a favor. How are my birds? How do they like their new home in your apartment? Would you mind . . . would you mind putting the phone next to the canary cage?” Gia raced on. “I want to hear my birds sing.”

“Sure,” Dore replied. “Sure.” He pulled the phone extension-cord out full length and turned the mouthpiece towards Gia’s four canaries.

“Can you hear them, Gia?”

“Yes.”

For a full minute Dore Freeman held the phone next to the cage. When Gia’s mother had died, she’d asked him to take care of Gia. Ever since, he’d tried to make Gia feel a part of his own family.

Dore put the phone up to his ear.

“Gia? I want you to know that you’re the only girl who could make me stand here like an idiot and play sound man for four birds. I . . . Gia?” He heard sobbing. “Gia, what’s the matter?”

“Nothing. The bird’s singing. It’s just so beautiful. Dore? Are the flowers fresh on Mamma’s grave?”

“Yes, of course. Gia, you’re worrying me. You know what? Is someone with you? I don’t want you to be alone.”

“I had a house-warming party tonight,” she said. “There are still a few people here.”

“Gia.”

“Yes, Dore.”

“Don’t cry. Please.”

“l’m crying because I heard the bird’s singing, Dore. Goodbye.”

“Gia? Gia?” Dore called. But there was silence.

Gia replaced the phone on its hook—carefully, as if she had made a decision. The tears began again. She’d started to cry again. Then she stood up and walked across the room to a bureau. She’d gone there to get a tissue, but as she looked down at the bureau, there was that letter, postmarked Hollywood. “I thought you and Buddy Bregman were ablaze . . . Did you know he became engaged recently . . .?” The letter hurt, she didn’t know quite why.

Gia had moved heavily through the past few days. It was as though a dark cloud had covered her world and she couldn’t lift it.

She found herself thinking more and more of her mother. Perhaps it was seeing her father again, here in London. Perhaps it was because, the last time she had been in London, her mother had been with her . . .

Gia’s hands hung lifelessly at her side. She walked back to the bed, the tears coming more quickly now. In the other room, a few stragglers were keeping the party going with jazz records.

“I should join them,” Gia thought. She took a half-step towards the door. “No,” she whispered. “I can’t.” She sank down on the bed, burying her face in the pillow and sobbing, “Mamma mia, Mamma mia.”

Somehow, she drifted off into a troubled half-sleep. Suddenly—she didn’t know how much later—she awoke with a start. She brushed the strands of hair from her tear-streaked face and listened. Something was wrong! Why was it so quiet? She glanced at the little clock on the bedside table and was shocked to see how much time had slipped by. She rose and walked to the bathroom. She put cold water on her face, and then warm water, holding the washcloth to her eyes to bring down the swelling. She reached for her makeup kit and used the tricks she had learned from studio makeup men to put on her “happy face.” A final straightening of her dress, a last quick glance at herself in the full-length mirror, and she opened her bedroom door and stepped out into the living room.

It was empty. Her guests had left. She was alone again. She heard a noise on the terrace. She walked across the room, cautiously glanced out into the misty darkness. A man sat in a chair by the railing, staring off into the murky darkness. Pietro Scoglio turned when Gia approached and smiled as she stood beside him.

“Papa. Ma che cosa fate?”

“I am doing nothing, Gia. I just wait for my little girl to find her Papa.”

“Have you been here long?”

“Well, I come very early, but you have friends. So I sat across the street in the little restaurant until they leave. I do not want to impose myself.”

“Do not talk foolishly—you are my Papa, I am your daughter.”

“Perhaps sometimes we forget.”

“Oh Papa, what’s wrong with me? Why can’t I get over Mamma’s death?” Gia cried and sank to the floor of the terrace, resting her head on his lap.

“Gia. Figlia mia. The tears still come when you think of your Mamma? She would not be happy to see the pain you have in your heart.”

But Gia was not listening. She was back in the hospital, outside her mother’s bedroom, remembering their last day together. Her mother was dying of cancer and Gia was playing another role—perhaps the most difficult—pretending all was well and that her mother would soon be better. She had carried champagne to her that evening and she and the doctor toasted Eileen Scoglio. They laughed and had another glass when Mrs. Scoglio asked to return their toast. And then the doctor had taken Gia aside.

“. . . Is there any chance that Mamma will get better?” she asks the doctor.

“No,” he answers, “none.”

“How long?” she asks.

“A few weeks, maybe less. With cancer, it’s hard to say for sure.”

“Does Mamma know?” Gia asks quickly, twisting the corners of a handkerchief she holds.

“I don’t think so,” the doctor answers.

“She must not know,” Gia says.

The night nurse turns out Mrs. Scoglio’s bed-lamp and Gia tiptoes down the hall toward the elevator. I must go where I can think, she says to herself. I must go where I can think . . . and pray.” So Gia climbed into her car and headed for the ocean, for the Pacific, where she could walk on the sand and gaze at the ocean and be close to God.

As her sportscar rounded a sudden curve on the steep hill leading to the beach, she suddenly lost control of it, crashing into a hedge in front of a house and battering her car. By some miracle, she was unhurt. But the humiliation that followed made Gia feel grateful that her mother never knew what happened. She was taken to the police station, booked on suspicion of drunken driving, and for three hours remained there, until her bail was raised.

She remembered being in the courtroom the next day—telling how she and her mother had the champagne together. The case was dismissed, but she resolved never to take a drink again.

Gia, are you listening?”

“Excuse me, Papa. My mind was floating away.”

“I understand, Gia. But I want to talk to you. Those people . . . that dancing . . . all that noise, that’s not . . .”

“Papa,” Gia interrupted. “Tonight . . . I was trying so hard . . . so hard to have fun. You shouldn’t stop me. . . . Mamma wouldn’t have.” She was silent a long moment. Then she said quietly, “I must take a walk.”

“Now, Gia? But it is so late. A girl must not walk the street alone.”

“I must get away. . . . Someone is waiting.”

“I do not approve.” slightly raised.

“Papa, you never did.” Then she dashed out without saying goodbye, leaving her father behind. But he rose and followed her.

Leaving the apartment lobby, they stepped into the night. The darkness—the damp coolness that surrounded Gia frightened her suddenly. That feeling was with her again. She was alone—the darkness was covering her up. She couldn’t push back thoughts of her mother. . . . At the burial she had wanted to cry out, “You are covering up all the goodness and warmth I possess. You are covering up my soul. I am dead now.”

Suddenly Gia broke away from her father. She had to get away from him, to be far away from him. He’d been far away, in Italy, when Mamma had died. It’s too late now, she thought bitterly, for Papa and me to be together.

Gia hailed a taxi and, entering, fell back against the cushions helplessly.

“Take me home, driver. I mean, Chresham Street.” The taxi started to move down the street. She leaned further back against the cushions. She was so tired. She leaned forward suddenly and called to the driver, “Take me to Waterloo Bridge first. I want to look at the water.”

“Yes, Miss,” the driver said, and headed for Waterloo Bridge. Gia glanced at the little identification card pasted to the window dividing the car in half. “Mr. Moss? Mr. Moss, are you married?”

Morris Moss adjusted his rear vision mirror so that he could see his passenger. “Yes, Miss, for thirty years.”

“Are you happy?”

“Yes, Miss. Begging your pardon, Miss, but don’t you think it’s a little late for you to be driving around London? Wouldn’t it be better if I took you home?”

“No,” she said. “I must go to the Bridge first.”

“Wouldn’t it be better to get some sleep, Miss?”

“No, Mr. Moss.”

The taxi approached the bridge. “Stop here, please,” Gia said. The taxi stopped about one-fifth of the way across. Moss got out and opened the door for her. “That will be six shillings, Miss,” he said.

“Six shillings,” she said, “Six shillings. I have no money. I left it home.”

“That’s a good place for you to be, Miss. Home. Let’s go there and you’ll pay me then.”

“No,” Gia said. “Here’s my ring. It’s worth much more than six shillings.”

“I couldn’t take your wedding ring, Miss.”

“But it’s not my wedding ring. The studio gave it to me when I played the widow in ‘The Garment Jungle.’ But it’s good. Honest it is.” She dropped it in his hand, ran to the stone parapet and started to climb up.

The cabbie ran after her and grabbed her hand just as she was slipping over. He held her as he called for help. Two other cab drivers drove up and helped him in dragging her to safety.

On his cab radio Morris Moss called the police. They arrived in a few minutes. While two policemen stood on either side of Gia, Moss told the story. When he was done, Gia told her side of the story. Yes, she had asked to be taken to Waterloo Bridge but she hadn’t tried to commit suicide. She’d just wanted to get a better view of the Thames. She admitted it probably sounded like a silly thing to do, but she’d given a housewarming party and her head ached. Now the fresh air and the excitement had made her feel better and she wanted to go home. She would pay Mr. Moss.

She climbed into the taxi and the police drove away. Moss started the engine. Suddenly, his passenger darted out and ran for the bridge wall again. But she tripped and fell.

The police cars doubled back. They helped Morris hold her. She fought with them, tearing her dress. She bit one of the officers on the hand. “Let me do it! Let me do it!” she screamed.

“What’s your name, Miss?” they asked her.

She was silent.

They took her to the Bow Street station, where she refused to give her name or any information about herself. The policemen offered her tea, cigarettes and hot food. She refused everything, huddling in the corner of a bench like a tired puppy. After two hours she fell asleep.

She woke up with a start to see her father. His coat covered her. She put her arms around him and sobbed. He held her tight, and rocked back and forth as if she were a little girl once more. “Gia, Gia mia,” he said, and she saw that he was crying. “Giosi,” he said, “Giosi.”

Tears flooded into her eyes. “Papa, Papa,” she cried. “You haven’t called me that—‘Giosi’—since I was a little girl.”

“Giosi,” he said, “I don’t know how to say it . . . but about tonight. I’m sorry. That kind of dancing, that music, all the noise . . . I just don’t understand.

“Mama wouldn’t have said ‘Stop’ to you tonight,” Gia’s father went on. “I remember when we were all in Italy and you were a little girl. There’d be a party. Five or six girls. Maybe one little boy, somebody’s cousin. I was strict. My father was strict. I knew nothing else. ‘No party for Gia,’ I said. ‘No party where there’s a little boy.’ Foolish, sure. Now I know—foolish. But then, my word was law. Bad law but my law. But your mamma—she knew how to make me break my own law. You know how she’d do it? She’d tell me that she loved me. And me—big man, big law-maker—I’d melt like spumoni in the sun. And you’d go to the party.”

Gia looked at her father. “You miss Mamma, too. You miss her very much. I never knew. All the time Mamma and I were in Hollywood and you were back in Italy I thought . . . I don’t know what I thought.”

“You’re like your mother, Gia. And I—I love you. I need you. . . . I want to help you. I’m no good with words.”

After a while Gia said, “Take me home, Papa.”

Mr. Scoglio talked to the policemen for a while and then Gia was released in his custody. As they were about to leave, Gia asked her father for some money. “Here,” she said to the man at the desk, “please see that Mr. Moss gets this. And thank him for me. And I’m sorry for all the trouble I’ve caused you. Please forgive me. I’ve been very blind.”

And then she turned to her father and, looking directly at him, said, “But now, at last, I can see.”

He put his coat over her shoulders and they walked into the night. The gray mist didn’t frighten Gia anymore. She shuddered because of the cold air and leaned closer to her father. Together, perhaps, they could face the future.

THE END

GIA STARS IN “THE CLOCK WITHOUT A FACE” FOR COLUMBIA AND “THE ANGRY HILLS” FOR M-G-M.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1958

No Comments