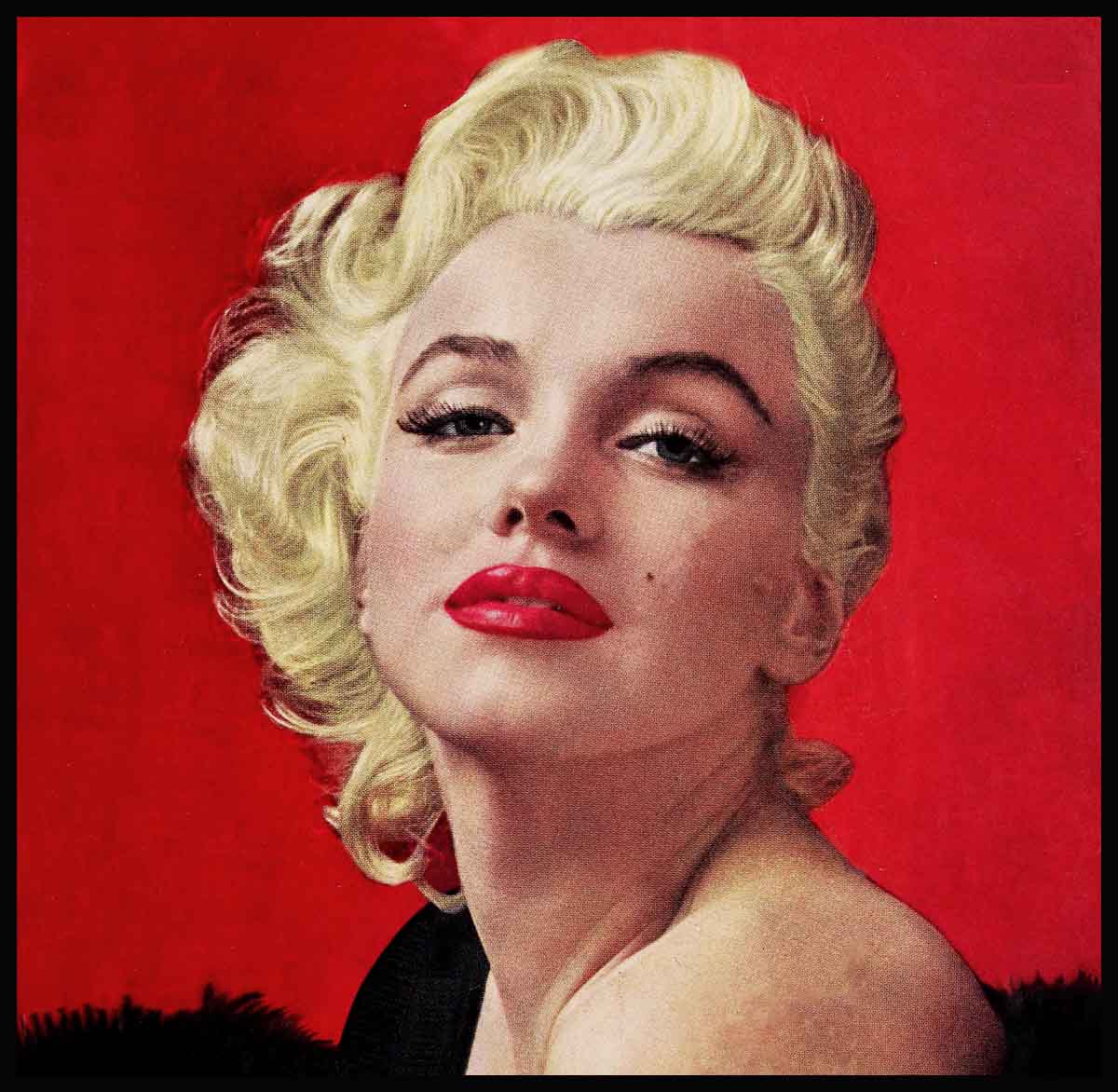

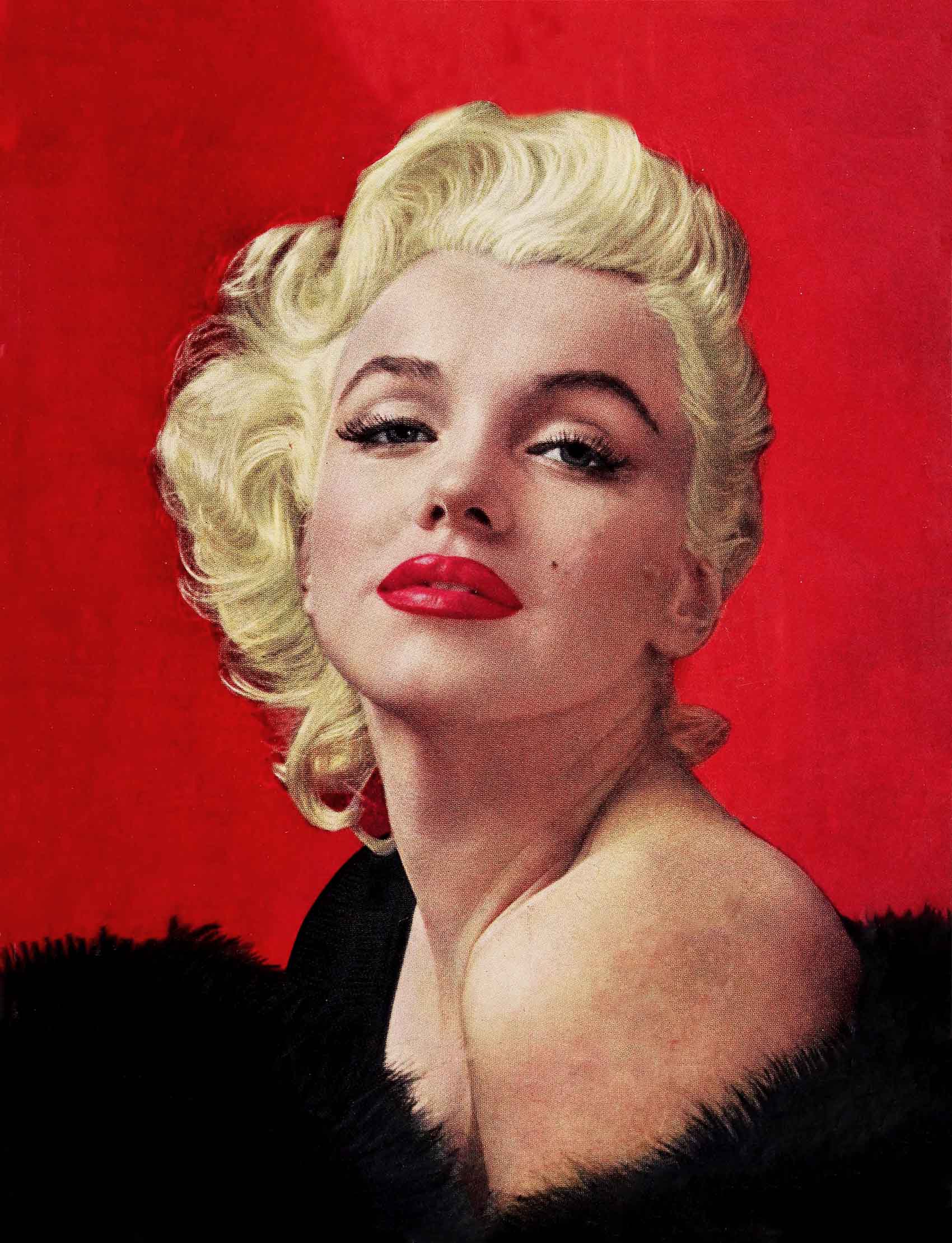

In Defense Of Marilyn Monroe

People have been saying to me lately, “Marilyn Monroe must be all mixed up.”

I disagree. I think Marilyn knows exactly where she’s going—and that it’s forward. It’s just possible that she’ll turn out to be not only the sexiest but the smartest blonde of our time.

Marilyn has a knack of getting what she wants—especially from men—by acting rather vague. Some superficial observers would think she’s just a frivolous blonde.

But she isn’t. In New York recently she posed with some posters advertising the Rheumatism and Arthritis Fund. Several reporters turned out for a press party at Sardi’s, and some of them began to pepper her with questions about whether or not she was going back to Joe DiMaggio.

“Oh, let’s talk about arthritis,” begged Marilyn.

The reply was just preposterous enough to make the reporters laugh and drop the questioning.

Marilyn got what she wanted—no more questions—by this little trick. Right now she wants to act and to get well paid for it. I predict she will.

I was present at a big Actors Studio party which she stole completely although the biggest stars were there. And I witnessed something that shows she is respected as an actress around Broadway.

“Could I get her autograph?” asked Lawrence Langner of the Theatre Guild, who has directed or employed the greatest stars, including Katharine Hepburn and Helen Hayes.

I transmitted the message to Marilyn. She inscribed a card, “Love and Kisses,” and then her name—and when I mentioned who he was, she said:

“I should get his autograph!”

And he gave her one of the most glowing messages I’ve ever seen, it said:

“Dear Marilyn: We need you for our Shakespeare Theatre. Yours admiringly, Lawrence Langner. P.S. For A Midsummer Night’s Dream. What a dream!”

Langner told me the last time he had asked an actress for an autograph was in London in

1908—forty-seven years ago—and that her name was Zena Dare.

At first Marilyn was believed to have made a mistake by leaving Hollywood and coming to New York when she battled with her studio. But with the help of photographer Milton H. Greene and agent Jay Kanter of MCA, she did a good public relations job for herself in Manhattan.

She has so much warmth and charm that she won everybody she met—and she met many.

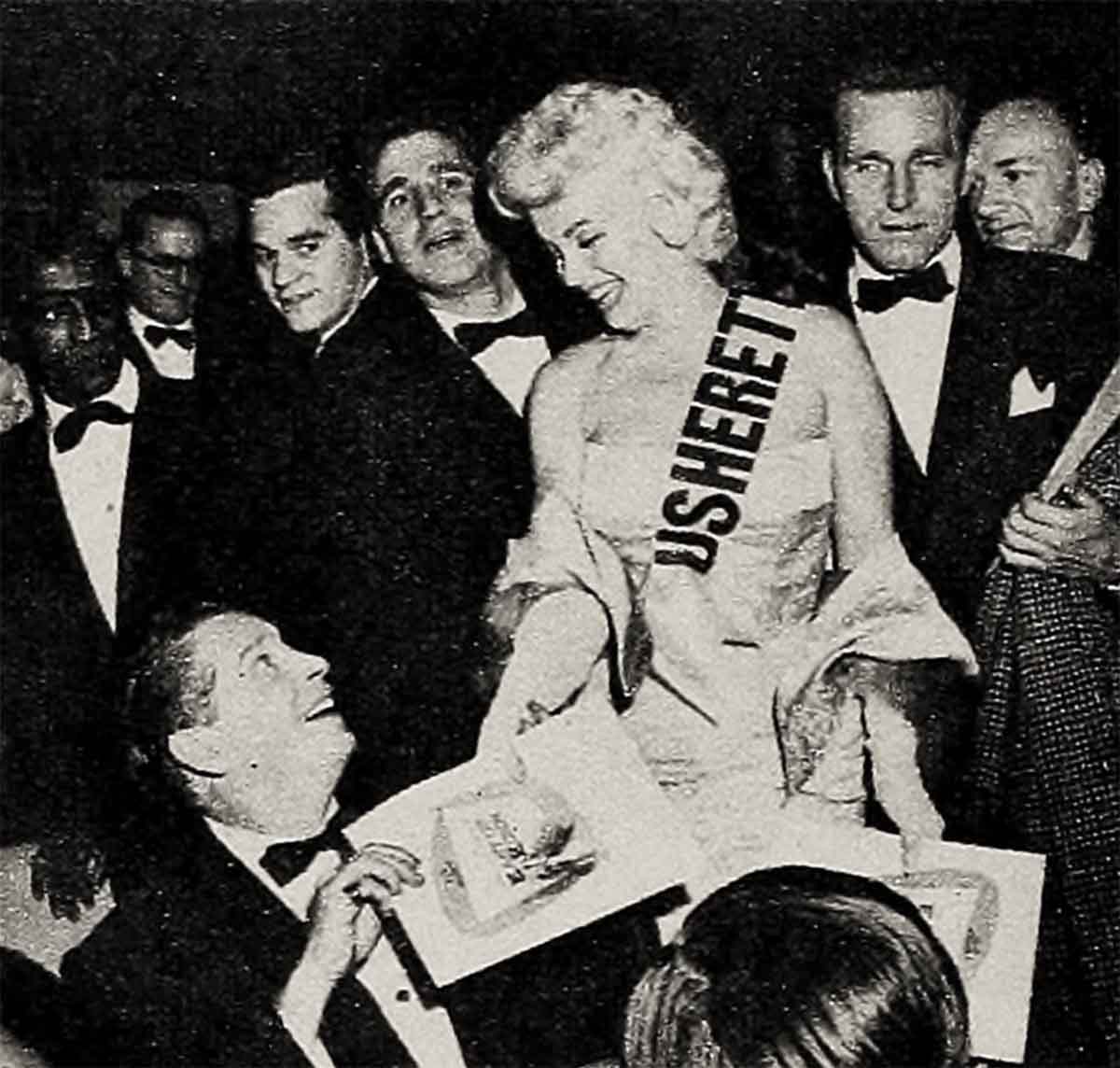

When she went to a premiere of East Of Eden to be an usherette, Marilyn was such a sensation that some of the other glamour gals did some jealous muttering.

A TV commentator interviewing Denise Darcel when Marilyn came in couldn’t, or didn’t try to, conceal the fact that he wanted to finish with Denise—and get to Marilyn.

Marilyn was also smart in refusing to sing “Diamonds Are A Girl’s Best Friend” at this party.

She hadn’t had time to rehearse the song. Furthermore, she might have been compared with others who’ve sung it, and as a Hollywoodite at a Broadway party, she might have been resented. She wisely just sat there at the party—and let all of the curious stars stare at her. And they surely did!

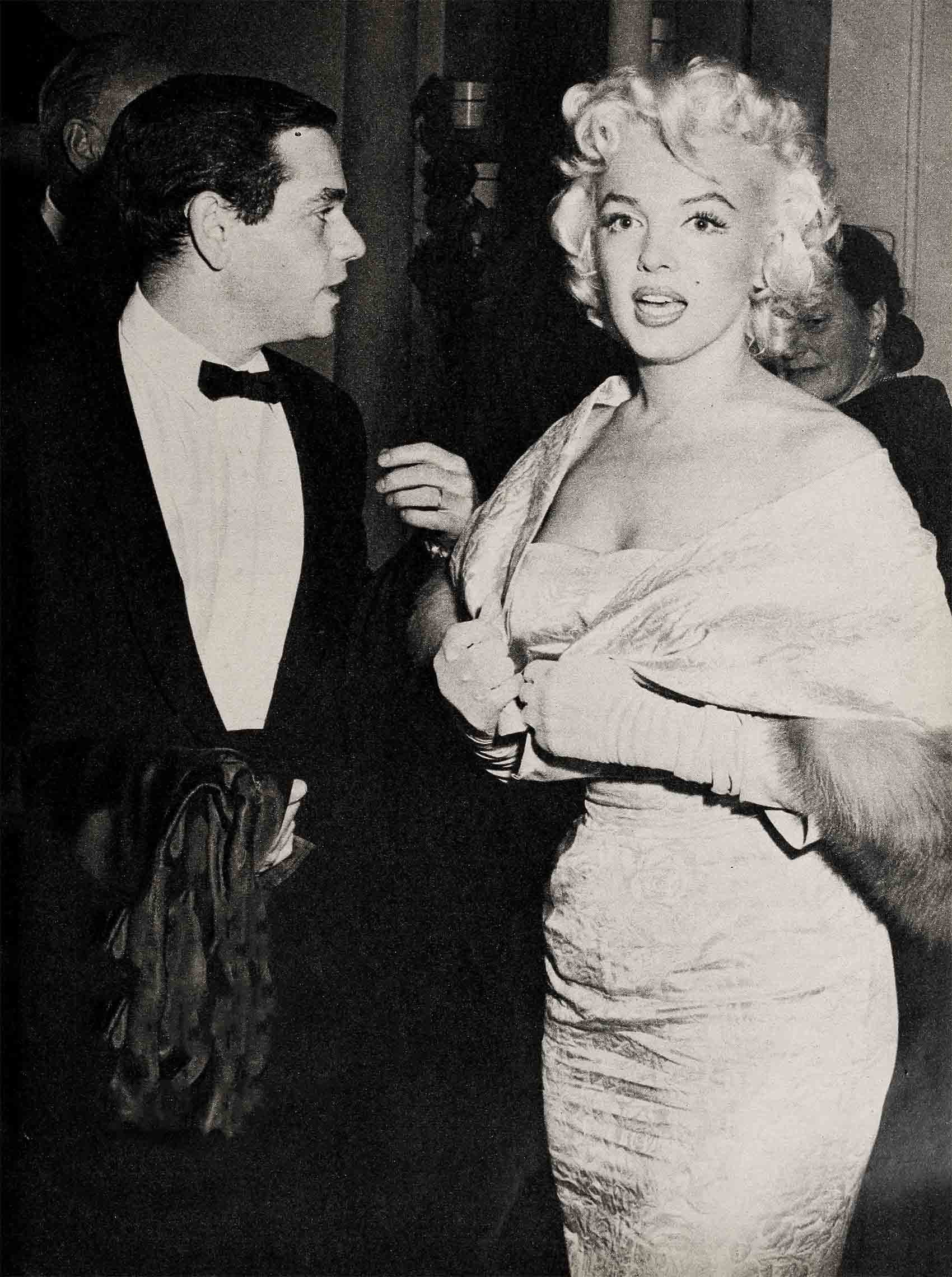

Marilyn also went to the big Friars’ dinner for Martin and Lewis, where she was the only woman on a dais of about forty celebrities.

Sitting between Eddie Fisher and Bobby Clark, she was the center of attention all evening. When she took a bow, and gave Martin and Lewis each a smooch, she won tremendous applause.

Marilyn admitted that she had one embarrassing moment that evening—when she left the dais to go to the ladies’ room.

“The President of the United States does that,” I told Marilyn. “At big banquets he leaves the dais to go to the powder room.”

“Then I guess I can do it,” said Marilyn. “I’m a president—of Marilyn Monroe Productions.”

Marilyn discovered that New York show people—supposedly hard and tough—have real respect for her. She hasn’t had one bad experience with them. Carol Channing had been urged to trap her into getting up on the floor to sing “Diamonds” with her at the Actors Studio party. But Carol thought it over and decided not to do it. I talked to her about it when she came off the floor.

“I decided it wouldn’t be fair to Marilyn,” Carol said. “I just know that I’d kill anybody who’d do it to me, so why should I do it to her?”

Many actors seemed to be going around asking, “Do you think Marilyn would mind this?” One of those was comedian Joey Adams, one of the dais-sitters.

“I’ve got a gag about Joe and Marilyn. Do you think I should tell it?” he asked a friend.

“No,” replied the friend. “There’s nothing wrong with the gag, but it might be embarrassing to her.”

So Joey chucked the joke.

While she was around New York, Marilyn doubled her contacts and acquaintances—and nearly every new one was on her side.

One of the funniest experiences she had was at Jackie Gleason’s thirty-ninth Barthday party at Toots Shor’s.

“I’ve got splinters!” she suddenly announced, patting the area where she had them. Everybody laughed—and several gentlemen volunteered to help remove them. Marilyn didn’t laugh, though. She hustled off to the ladies’ room.

My wife and another guest at the party happened to be there and they helped yank the big splinters out of the Monroe epidermis. Marilyn got them by sliding down into a chair. She demonstrated to my wife how it happened. And my wife said that Marilyn gives a chair a caress when getting into it—sort of oozing into it—and that the splinters are to be expected if one has watched her get into a chair. In Fort Wayne, Indiana, a group of fans got up something called “The Society for the Prevention of Splinters In Marilyn Monroe.”

Marilyn was the hit of that party, too. Joe DiMaggio escorted her to it. Later on Joe happened to be at another party—and Gleason phoned him that he was coming to it.

“I just want to warn you that I’m bringing Marilyn,” Gleason said.

Sure enough, he arrived with Marilyn—his girl friend, Marilyn Taylor of the June Taylor Dancers.

One of Marilyn’s big excitements in New York was helping to stage a surprise party for Milton Greene, the vice-president of Marilyn Monroe Productions.

Greene’s pretty wife Amy got Marilyn to help. So Marilyn and Agent Jay Kanter called a meeting of Marilyn Monroe Productions at about three o’clock on the afternoon of Greene’s birthday at the Hotel Gladstone where Marilyn was living.

“Keep him out till six-thirty,” Amy directed.

“We had a hard time with Milton,” Kanter told me later. “We transacted all the business in a couple of hours. But we had to keep him another hour.

“So Marilyn would say, ‘Oh, that reminds me of something else I’ve been wanting to take up.’

“We’d dispose of that in a few minutes and Milton would say, ‘I’ve got to be going.’

“Then I’d say, ‘Oh, here’s something else to worry about.’ ”

Marilyn, Kanter and Greene finally arrived at Greene’s studio at about six-forty-five and everybody shouted, “Surprise!” to Greene, who really was. Marilyn was wondrously happy, for she felt she had put it over—and she had.

“It’s the first time Marilyn ever had a surprise party for anyone,” Amy said.

Greene, who is thirty-three, has excellent taste, and is primarily interested in seeing that Marilyn is not cheapened or “pushed around.”

Photographing her for one of the top magazines, he saw her as potentially a Great Woman. He didn’t photograph her the easy way—with a towel on—but brought out her sex appeal in a more dignified manner. One of his prize pictures of her shows Marilyn in a black robe. She’s well-covered. Only her bare legs show.

Yet this picture conveys the idea of Marilyn Monroe’s sex appeal far better than most—and still nobody can ever criticize Marilyn for it.

That’s the direction Marilyn wants to take with the help of the Greenes, who invite her frequently to their home at Westport, Connecticut.

Toward respectability. Marilyn has given serious consideration to the Broadway stage. She and Greene had a long meeting with George Abbott about the show, Damned Yankee, based on the book, The Year The Yankees Lost The Pennant.

“Marilyn should have a show written just for her,” Abbott said afterward. “With that personality, she’s entitled to it.” He felt that her sometimes faint voice is of a special quality which would be excellent in the proper show.

She’s had to take a lot of kidding in recent months because she said something about hoping eventually to do The Brothers Karamazov, by Dostoevski, and that’s a little unfair to her. The idea got around that she wanted to become a longhair.

“Why do you want to give up sexy parts?” she was asked.

Actually, the part she had in mind is very sexy. And anyway, she was talking about a picture she would like to do at some distant time. Marilyn knew a great deal more about the Dostoevski masterpiece than people who were joshing her about becoming a longhair.

Curiously, she is a well-read young lady. One book she read recently was Garbo and another was Ben Hecht’s Child Of The Century. The book about Garbo was given to Marilyn by a friend who inscribed it, “To one who is even prettier than Garbo.” Marilyn was especially interested in the sections of the book which told of Garbo’s battle with her studio.

At no time has Marilyn spoken out harshly against her studio.

“They’re all a wonderful group of people,” she says. But she has felt that she would have done better if she’d had a voice in choice of stories.

It didn’t make her happy to be in There’s No Business Like Show Business, alongside such expert singers and dancers as Ethel Merman, Donald O’Connor and Mitzi Gaynor.

“Ethel Merman is one of the greatest singers in the world,” points out a friend of Miss Monroe.

“Marilyn’s a good singer who’s learning a lot. But her singing would be bound to be overshadowed by Merman’s—just as Merman would be overshadowed if she tried to do a young sexpot role of the kind Marilyn can do so well.”

In The Seven Year Itch, Marilyn comes into her own, and makes up, she hopes, for another mistake, The River Of No Return.

“We should have had a stronger story,” is about all she’ll say about that.

Marilyn is so celebrated at this point that a columnist must always be checking a new crazy rumor about her. A recent one was that she and Rory Calhoun had been secretly married once many years. Ago.

I checked this one myself, going to the extreme of phoning Rory Calhoun’s Hollywood home. His wife, the lovely Lita Baron, answered at six-fifteen A.M.

She first said, “You’re not serious!” Then she told me, “This is preposterous.”

Suddenly, she said, “Oh, I know where that crazy story comes from. They were married in The River Of No Return.”

To me, there’s something significant in the way the autograph kids—the movie fans of today and tomorrow—talk about her. They’ll tell you that she’s wonderful, never too busy to stop and sign their books and pose for their cameras.

Never underestimate this gal. What other actress—during a suspension—has gone about making a million or so new friends?

THE END

—BY EARL WILSON

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE JUNE 1955

No Comments