Marilyn Monroe: “I Want To Be Loved”

One afternoon about eight months ago a friend of Marilyn Monroe decided to play Cupid and called her on the: phone.

“You’re always saying,” he began, “how tough it is to meet nice eligible young men in Hollywood.”

“That’s true,” Marilyn said.

“Well, I’ve got a great guy for you to meet tonight,” the friend continued. “I’m sure you’ll like him.”

Her curiosity piqued, Marilyn insisted upon knowing something about her blind date. “Is he in show business?” she asked.

“He’s not in show business,” the friend said, “but he’s the sweetest man right now this side of the Mississippi. Honest! I’ll pick you up at eight. We’re dining at the Villanova.”

The Villanova is one of those warm, intimate, Italian restaurants with soft lights, candles on the table, bottles of Chianti, platters of antipasto, and huge casseroles crammed with spaghetti and meat balls.

Joe DiMaggio, one of the greatest baseball players in the history of the game, was sitting in a booth waiting. As Marilyn and her friend approached, the tall, dark, thin-faced outfielder rose quickly to his feet. He was introduced and they both smiled, pleased with their fate. For a minute they looked into each other’s eyes, saying nothing. Then the conversation began, easy, simple, exploratory. How did Joe like it out here? Just fine. How did she feel being a movie star? Well, she wasn’t really. In fact she was just a very small movie star.

Joe DiMaggio and Marilyn Monroe are basically simple, honest, forthright people, and over the dinner table that night, there was no attempt by either of them to sound sophisticated or witty or worldly.

Joe explained that he’d retired from baseball and was working as a telecaster in New York. He had a 9-year-old son, Joe Jr., going to school on the West Coast. As part of a 1944 divorce decree, he shared custody of the child with his former wife, actress Dorothy Arnold. He himself came from San Francisco. Had Marilyn ever been to San Francisco?

Marilyn smiled. “About five years ago,” she said. And then she told how one day early in her career she happened to run into Doc Shurr walking down a street in Beverly Hills. As Bob Hope’s agent, Doc knows all the latest town gossip. Marilyn was looking for a job at the time and he sent her around to see Groucho Marx. Groucho was casting an atrocity, later to be entitled Love Happy.

When Marilyn called at the office, Groucho took one look at her. “Don’t say a word,” he insisted. “You’ve got the job.”

“The job,” Marilyn recalled, “consisted of Groucho chasing me across a room. It took only 60 seconds, but I got five weeks work out of it because they asked me to go on a personal appearance tour. That’s when I played San Francisco.”

As the dinner dwindled down to dessert, the friend who had brought Marilyn and Joe together made a diplomatic exit.

Joe was extremely grateful; so, too, was Marilyn. In the course of the evening a rapport had sprung up between the two of them. Now they wanted to be alone, so Joe thought of a way.

“How about riding around town a little?” he suggested.

Marilyn nodded. It was one of those bright, clear California nights when even the smallest stars are allowed out, so they drove along the Sunset Strip. Gentleman that he is, Joe asked the beautiful blonde if she’d like to drop in at the Mocambo or Ciro’s or any other night spot. When she said no, he was secretly glad. That night Joe didn’t want to share Marilyn with anyone.

They parked on the Doheny bluff overlooking Los Angeles, and oddly enough, it was Joe who pulled the switch. Usually its the girl who brings out the autobiography in man. Not this time. Joe asked Marilyn to tell him all about herself and she gave him the straight dope, how she was born Norma Jean Baker and bred in Hollywood, how. she was raised partly in orphanages and partly in the homes of adopted parents. “I was married when I was 16,” she said quite candily, “divorced when I was 17, graduated from high school when I was eighteen.”

Joe asked how she’d broken into movies.

Again Marilyn told the truth—not the souped-up baloney the publicity agents bandied about but how it had really happened.

In 1945 she was working as a parachute inspector in Reginald Denny’s model plane factory. A photographer from the Army came around to shoot stills of the female aircraft workers, thought it might boost the morale of the boys fighting overseas. “A sergeant named David Conover shot a few stills of me,” Marilyn explained, “and two weeks later local photographers began phoning, offering me $15 an hour to pose as a model. Since I was only averaging $22 a week at the aircraft plant, you can bet I switched jobs in a hurry.

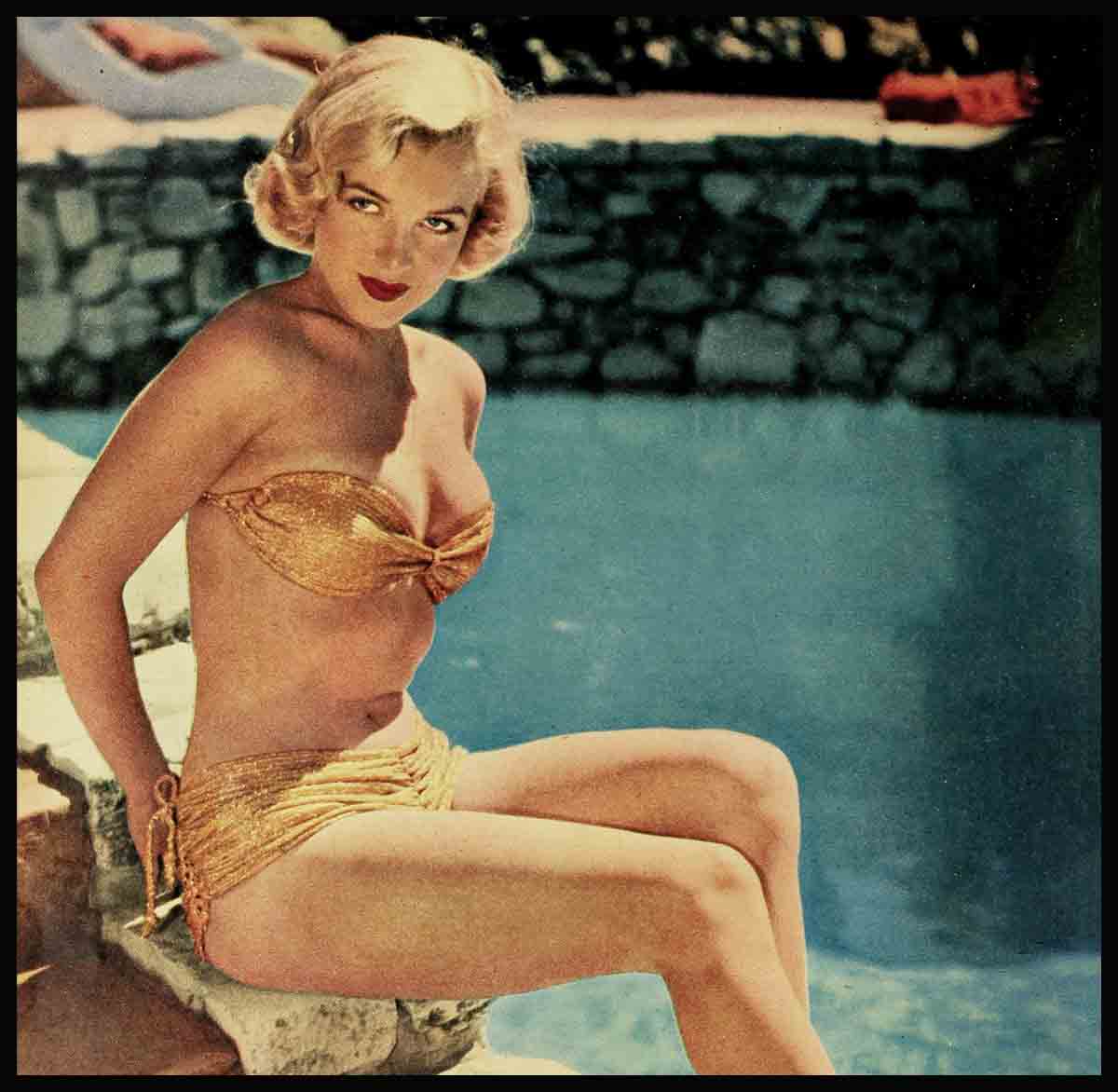

In August of 1946 after her face and figure had appeared on the covers of five national magazines, 20th Century-Fox agreed to give Marilyn a screen test. It came out well, and she was signed. Six months later the studio dropped her, as one of the casting directors termed her “absolutely hopeless.” Three years later this same executive had to admit he was wrong, and Marilyn was signed again.

Joe DiMaggio was smitten that night, not only by Marilyn’s beautiful face and curvaceous figure but by her patent honesty, her lack of pose. Here was a girl after his own heart, the kind of simple, earthy, basic girl he once felt sure he could never find in Hollywood.

A few nights later, Joe, who always stays at the Hollywood Knickerbocker during his west coast visits, checked out of his hotel and flew back to New York and his television program. He was definitely in love.

When the New York Yankees hit the road and Joe had some free time, he winged back to the West Coast. Reporters who asked him what he was doing in town again were told that he’d come to visit his son. “He goes to school here, you know,” Joe told them.

DiMaggio not only saw his son while he was in Hollywood but he also brought the boy out to the Bel-Air Hotel to meet Marilyn Monroe. That’s what started. the hullabaloo, the rumpus between Joe and his ex-wife and Marilyn.

When Dorothy Arnold learned that Joe had taken Junior to meet his new love, she reportedly blew her top and asked her lawyer to seek a modification of the 1944 divorce decree, giving her complete custody of the boy.

“I certainly want little Joe to see his father,” she said, “but I think it would be better for all concerned, particularly the boy, if the meetings were at my home.”

What is wrong with a 9-year-old boy swimming in the same hotel pool as Marilyn Monroe?

Anyway, DiMaggio, very upset, flew back to New York. Marilyn, deeply hurt, checked into a hospital for the removal of an appendix.

I was in New York when Joe arrived. I reached him at the Yankee stadium before the start of his TV show. “What happened out in Hollywood?” I asked. “Why did Dorothy object so strenuously when you took the boy along on a date? Does meeting Marilyn Monroe constitute grounds for demanding full custody?”

Joe shrugged his shoulders. “I sure can’t understand it,” he said. “The boy and Marilyn met only for a couple of hours. There were at least a dozen other children swimming in the Bel-Air pool at the time. Everyone there was perfectly respectable. There was no drinking, and I certainly don’t know what’s wrong with spending an afternoon at a swimming pool.

“I picked the boy up last Friday and we went out to dinner. Then I took him to see a movie. We got home and he was in bed by ten. On Saturday we had breakfast together, and he said he wanted a beanshooter. I got him one and he shot a bunch of beans all over my room. We went for a drive together, had lunch at the Bel-Air pool and went swimming. I brought him back to his mother’s and I came on to New York. He saw Miss Monroe for about two hours. Is that a crime?”

Following this incident and the resultant publicity, Joe and Marilyn decided to be very circumspect about being seen together. They also decided to say very little about their romance, in fact, to deny it, to refer to it as a casual friendship.

When I asked Joe, for example, when he intended to make Marilyn his wife, he said, “Gee! We’re just good friends. We just happened to run into one“another.”

This was sheer hokum, of course. When Marilyn was sent to Niagara Falls in July for location shots (she plays the lead in the forthcoming 20th Century-Fox film Niagara), who was on hand but Joe DiMaggio. He returned to New York over the weekend, but, when the film was finished, Marilyn raced to the big city to be near him. She checked in at the Hotel Drake, and that night the lovers dined at Le Pavillon, one of the city’s plushiest restaurants. If they weren’t in love, they certainly gave a great imitation of it.

Joe took Marilyn around and showed her New York just as she’d shown him Hollywood. To avoid reporters, however, he took her to small out-of-the-way restaurants, places where they wouldn’t be seen, eateries in the suburbs located off the Bronx and the Hutchinson River Parkways. As Marilyn herself says, “I’ve been to New York before, but it was never so wonderful. I’ll never forget those days with Joe.”

When the studio called and Marilyn had to wing westward, Joe found himself terribly lonesome in New York. As soon as the Yankees hit the road, Joe hit the airlines. He flew to Hollywood again, his fourth trip in six months. He didn’t come to see the scenery, either. He just couldn’t stay away from Marilyn. As soon as he arrived, he went out to see her. She tossed a few things in a bag and he carried her into his Cadillac. “I want you to meet my family,” he told her.

They stopped in little towns en route to San Francisco and soon the word spread that Marilyn Monroe and Joe DiMaggio were eloping.

They weren’t. Joe’s parents are dead, but the woods around the Bay Area are jammed with DiMaggio relations, and Joe introduced Marilyn to all of them. They enjoyed seven unforgettable days in “heaven,” after which they drove down to Hollywood. Once more the rumor was circulated that they were heading for the preacher. But they arrived in Hollywood single.

Next day a columnist announced that Joe and Marilyn had originally intended to get married on that trip, only the studio had prevented it. The story still persists that studio executives do not want Marilyn Monroe to marry for fear she will lose her undeniably increasing box office appeal.

“There are millions of men,” one executive told me, “who vicariously look upon this tomato as their own secret property. They go along with the illusion that she belongs to them. Suppose they read in the pavers that she belongs body and soul to DiMaggio. The illusion is broken.”

Admittedly, this is an outmoded theory but many studio executives still believe in it.

Marilyn herself says, “My. career comes out of my life. My life doesn’t come out of my career. When I want to get married, I’ll get married.”

Marilyn’s contract with 20th Century-Fox has another five and a quarter years to run. If she wants to become Mrs. DiMaggio, the studio can do nothing about it. The contract contains no clause prohibiting marriage.

Why then don’t Joe and Marilyn go ahead and tie the knot right now? Marilyn has moved out of the Bel-Air Hotel. She’s rented a cute little house high in the Hollywood hills, a home in which she and Joe could be ecstatically happy.

The answer is that Joe works in New York, and the love of his life labors in Hollywood. Joe has been identified with the New York Yankees for so many years now that he regards New York as his second home. He hates to sever all connection with the Yankees, and yet he will not ask Marilyn to abandon her career and move to N. Y.—not after the incredibly tough time she had in establishing herself as an actress.

Marilyn, who’s had one unhappy marriage and one unhappy love affair (with her agent, who died) says, “More than anything else in-life I want to love and be loved. A career is a very nice thing, only you can’t kiss it on the lips at night.”

And yet, despite giving tongue to such thoughts, Marilyn has no intention of sacrificing her career for marriage—not at this point, anyway. She feels she can have them both.

She is currently earning $750 a week. After giving money to her mother each week, paying her agent, putting money aside for taxes, the Screen Actors’ Guild and the Motion Picture Relief Fund, her net is about $400 a week, forty weeks a year, or an approximate annual income of $16,000.

Out of this she has to pay rent, clothe herself, feed herself and pay car expenses.

“I’m not complaining, however,” she says. “It’s more money than I ever thought I’d see and I’d like to enjoy it.”

Marilyn won’t come right out and say it, but she is hoping strongly that after Joe finishes telecasting the current baseball season in New York, he will return to the West Coast and look for a similar job.

When and if Joe goes to work on the Pacific Coast, you can bet dollars to doughnuts that Marilyn Monroe will become the second Mrs. Joe DiMaggio.

THE END

—BY IMOGENE COLLINS

(Marilyn’s latest movie is 20th Century-Fox’s O. Henry’s Full House.)

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1953