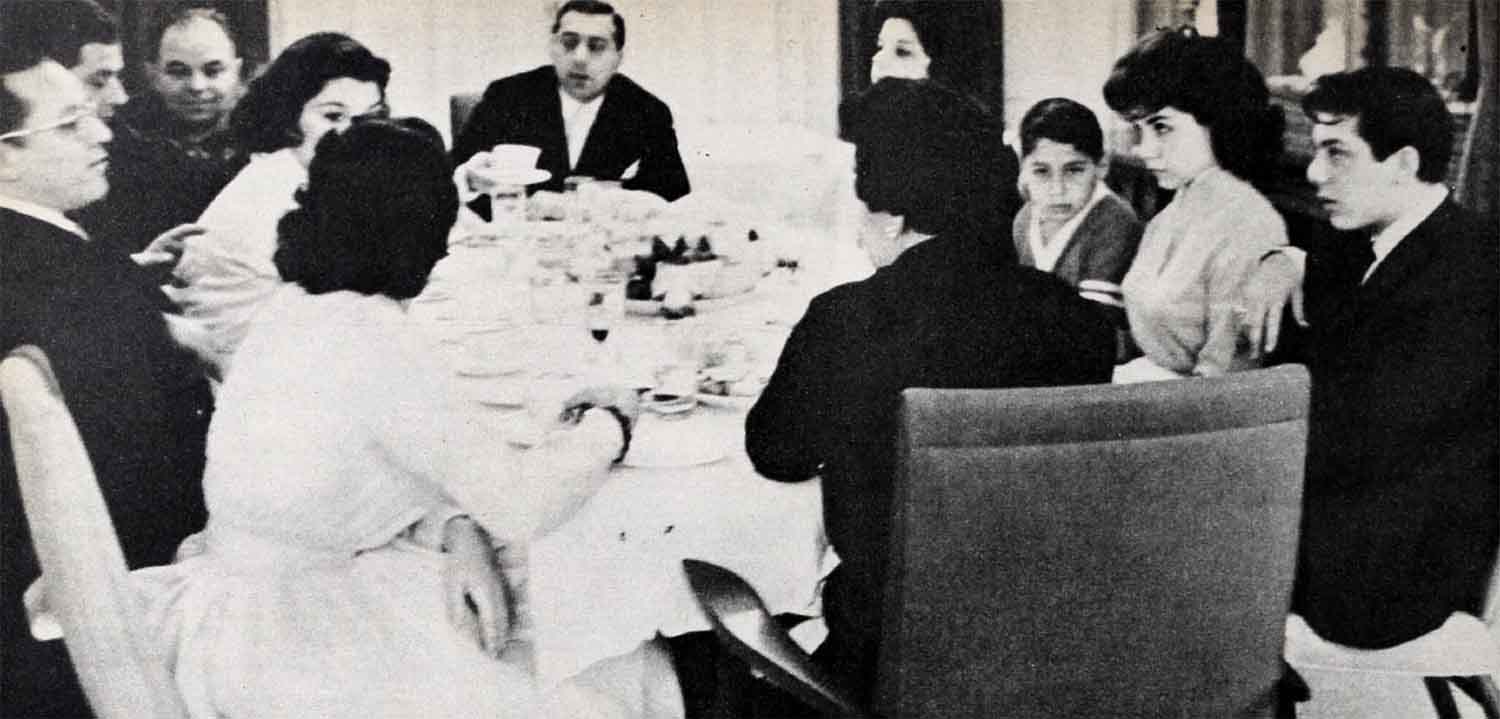

What Happened When Paul Took Annette Home To His Mother?

“Paul was a boy who got every kind of music lesson he ever asked for,” Mrs. Anka said across the table to her guest, Paul’s best girl, Annette. “We only wanted his happiness — and to Paul, happiness meant music.” Annette was listening, all attention. Paul had brought her home to meet his folks for the first time. It was fun hearing the old stories about Paul. At first, he pretended he was amused, too, but she could tell he didn’t like it when his mother said, “Paul had piano, voice, violin, drums—but he didn’t stick with anything. He was always too impatient.” And Paul’s father, Andrew Anka, said, “Impatience —that was his middle name! Always on the jump. When he wanted something, it had to be right away—not in a little while. And half the time, when he got it, he didn’t want it for long. He wanted the next thing.”

AUDIO BOOK

Annette watched Paul’s face. She could tell a mood coming on. He was just sitting there and not putting anything into the conversation any more. A silence seemed to settle over the whole table It wasn’t comfortable for Annette, and she felt sorry for Mrs. Anka who had cooked a delicious meal and set a pretty table, making the visit into a big occasion—an occasion that flopped! But, most of all, she was sorry for Paul because he was sad again. And when he was sad, she felt it right along with him somehow.

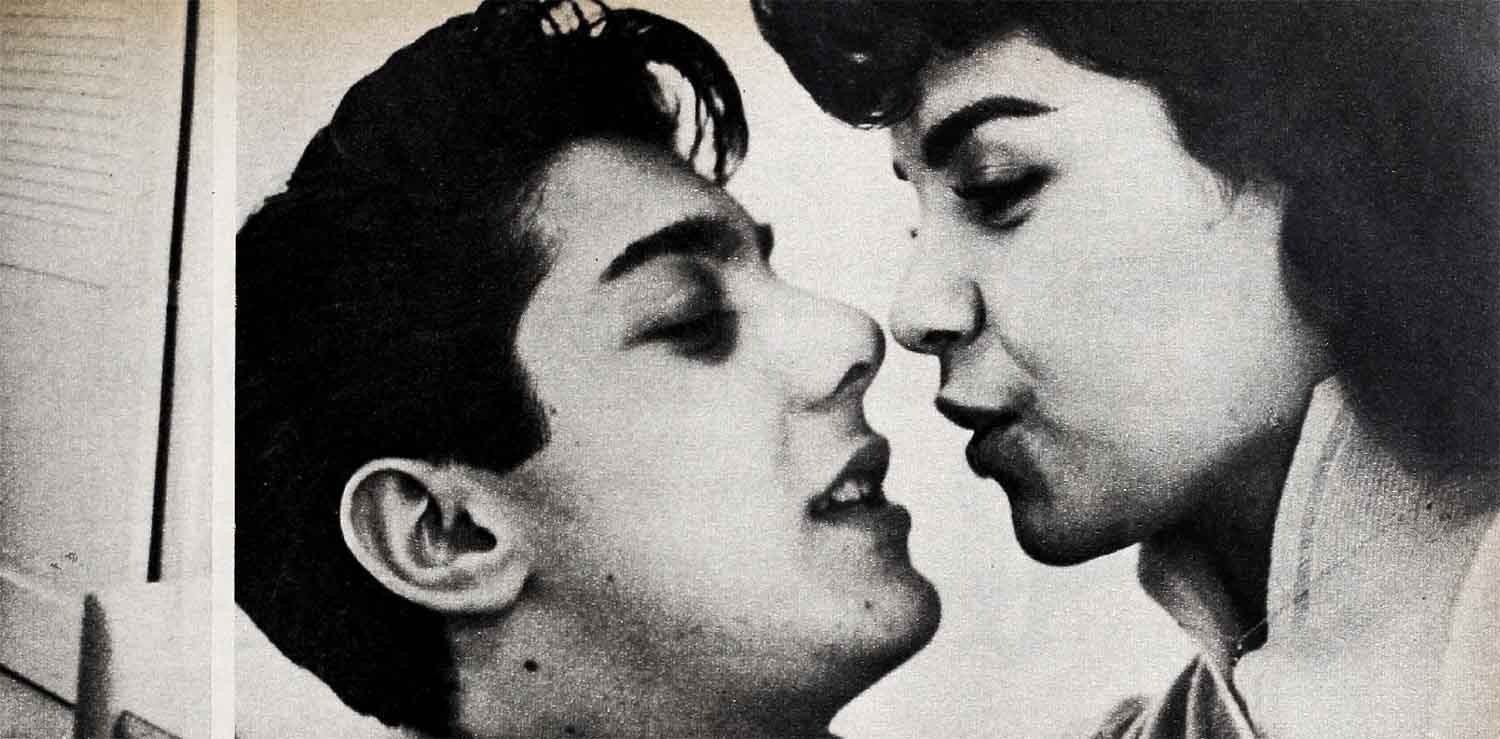

It was a relief when, after the coffee, Paul whispered, “Come outside with me, Annette. Let’s be alone for a little while.” They went out and sat as far from the house as they could get.

Annette coaxed, “Don’t be blue, Paul, they didn’t mean to poke fun at you, they were only trying to entertain me.”

Paul sat brooding, quietly, until he burst out, “It isn’t them, Annette—it’s me. They’re right—I was a mixed-up kid, never sure exactly what I wanted. But what bothers me is I’m still mixed up! When am I going to know? When am I going to be sure what life’s all about?”

Annette bit her lip, and thought, does he mean us? Does he mean marriage? But this was nothing a girl could say, or ask. So she told him, comfortingly, “Paul, you’re only eighteen. Give yourself a chance!”

Her concern, so sweet, moved Paul to tell her something he hadn’t intended to. Something he had kept from her, and his mother, and his whole family—until now he felt the need to reveal it—and himself—to Annette. He told her what had happened on his last hop to Europe. . . .

They were an hour out over the Atlantic when suddenly a sputtering sound on his side of the big Air France plane snapped him out of an exhausted doze. Lights suddenly flooded the wing, showing one propeller fanning to a stop, and gasoline leaking from the tanks. At the same time, the cabin blacked out. Stewardesses with flashlights explained the danger.

“There is a fuel leak. We’re circling back to Montreal. Please fasten your seat belts and remain calm. There’s only a little danger.”

Paul wasn’t so sure. He noticed revved-up engine’s sparks dangerously close to the escaping gas. If they set it off—they’d all blow up in flames.

“Why,” he told himself, “I can’t die like this. I’ve hardly lived!” He prayed. And then, miraculously, they were safely down, the whole thing an unbelievable night-mare. He had just toured practically all of Europe and Japan, Australia, Hawaii and Africa, this boy who had “hardly lived.” He’d set records at the famous Olympia in Paris. and on the Riviera. In Tokyo, they’d staged a ticker-tape parade in his honor. In Osaka, thousands stuck out a typhoon to greet him. In Helsinki, Finland, he’d sung for two hours, in driving sleet, to 20,000 people—without losing a listener!

And, yet, something was missing. Paul knew it then as he knew it today, sitting here with Annette. “Sometimes on that European tour, I’d find tears welling up,” he went on. “I’d lie on my hotel bed, all wound up after a day of the wildest cheers.” Yet he couldn’t say exactly why. Coming into the Georges Cinq Hotel in Paris, a bunch of French teenagers invariably flocked around him. “Come on, Paul,” his older troupe members would say. “Break it up and let’s rehearse.”

“No,” he’d answer them, arrested by a disturbing tug. “You guys go in. I want to stay here a while.” So he’d sit on the brick wall out front, buddying with kids his own age, messing around and talking about things that the people he traveled and worked with wouldn’t care about, or even understand. Then he felt better.

It was funny: how some days in lots of places—Rome was one—he’d have to smuggle himself to safety in fire trucks or police wagons. He’d have to climb over walls or shinny down fire escapes, hide himself under long cloaks and hats, even paste on false mustaches—all to give them the slip. And yet, he really ached for someone like them to talk to.

At the plush Sahara Hotel in Las Vegas, where he’d made his American night-club debut last spring, he was like a fish out of water. All around him, gamblers clinked silver dollars at the gaming tables and bellied up to the bar. Even if he liked to drink or gamble, which he doesn’t, he couldn’t. He was too young. At the dinner shows, he shared the program with brassy Sophie Tucker, past seventy, with her risque patter and suggestive songs. In his own act he found himself practically apologizing for being in front of that sophisticated audience. “Every night, at the end,” he told Annette, “I’d walk off fast, without looking back, like a school kid running out of a room of patronizing adults.”

So, in Las Vegas, he got an idea. He’d give a free concert on Saturday at the high school auditorium, just for teenagers—two thousand of them. That way, he knew, he could meet kids. And it made him feel good.

“But then, it was so strange,” he told Annette. “One minute I was out in front of all those people. And then, suddenly, I was alone. What could I do here in this hotel room? Nothing but think of what I’d be doing if I was home! I’d think I’d be with the kids having fun—or would I have been? No, I guess not,” he frowned now. “It’s not the same anymore. They’ve heard my records and they think I’m different. They don’t know what to say and I don’t either. They may even resent me. Some-times, I think, ‘what’s happened to all my friends?’ and then ‘what’s happened to me?” He looked at Annette as if waiting for an answer. But she just sat there listening intently.

“It was that way when I went back to my home town, Ottawa, Canada,” he con-tinued. He’d looked up his best pals, the Quinn brothers and Tommy Wrangle, busting for things to be like always. They weren’t; there wasn’t much to say. All the things he’d planned, excitedly, to say and hear didn’t come out—either way. It was really just “hello” and then “goodbye” without real contact, and that lonesome feeling again.

“Like I’d hopped off a sleigh ride and hopped right back on,” he described it for Annette.

“I’m so young”

Once, before he moved his family to New Jersey, he got a chance to fly home to Ottawa. He wanted it to be a surprise, so he didn’t let the family know. When he arrived, nobody was home; the house was empty and still. He just sagged to the piano seat and fooled with the keys, be-cause that’s all there was to do. In a few minutes, he wrote “Lonely Boy”—and he also wrote about himself.

“I’m so young—and you’re so old. . . .” the words of “Diana.”

“And this is the way I feel!” he explained to Annette. “Like there were two Paul Ankas living in two different worlds.” In one, he’s a seasoned entertainer. In the other, he’s a kid who sometimes says gloomily, “I should be in school,” who likes to send for his mother to be with him on engagements, who can’t resist sophomoric pranks and was “as tongue-tied as a ninth grader on my first date with a girl named Annette Funicello.” When he finished with a shy smile, Annette squeezed his hand, touched by the very shyness he was confessing.

“I don’t know much about love, Annette,” he went on. He fumbled for words. “You know who was my first love? Miss McCrea, my third grade teacher.” And he went on and told Annette how he used to slip little gifts into her desk drawer and hang around after school, mooning. After she got married, he’d ride his bike past her apartment and stare forlornly until, finally, he snapped out of it. “When that happened,” Paul laughed, “I made up my mind never to fall in love again. I couldn’t have been more than nine at the time!” Annette started to laugh at this, too. “But then, along came Collette.” Paul continued. “She was a French girl who came to look after us kids when Mom worked at Simpson-Sears store, and Dad was at the cafe and had to work until 4 a.m.”

Paul fell madly in love with Collette. When she got a boyfriend, Louie, Paul sulked miserably and threw oranges at them as they sat on the porch.

“You love him better than you do me!” he accused bitterly. Collette tried to explain the betrayal. “No I don’t, Paul. I just love Louie in a different way. When you get a little older, you’ll understand.”

Now Paul was older at last—eighteen—and trying to make Annette understand how he felt about her. “Like one night, last December, I was tossing around in bed. I just couldn’t sleep. My manager, Irvin Feld, was trying to get some shut-eye. We’d just come from Hollywood—that was where I fell hard for you, Annette. Now, here I was in New Jersey and I couldn’t stop thinking of you.

” ‘Tell me’ I finally blurted out to Irv, `Do you think Annette really loves me? Do I love her?’ “

” ‘Paul,’ Irv said to me, ‘You know what I think? You’re infatuated. It’s puppy love.’

” ‘Puppy love—what’s that?’ I asked, and Irv told me. Next thing I knew, I yanked him out of the bed and downstairs to the music room. ‘I’m gonna write that song,’ I said.”

And, in twenty minutes, it tumbled out—words and melody. By five o’clock, Paul had scored it on a lead sheet. “Puppy Love” went to the top of the Top Ten. “And where I sob out ‘Help me—help me!’ I felt it that way. But I wouldn’t have known how to say it to you, Annette.”

A pretty fresh kid

This was the day Annette learned something else about Paul she never knew before—how, if anything bugged him, it was the fact that he’s only five feet six inches.

As a kid they’d called him “Shorty.” Like most small kids, he did everything he could to prove being little didn’t mean a thing. “Most people thought I was a pretty fresh kid,” he admitted to Annette now. “Mother doesn’t kid when she says I was a little devil most of my life.”

At Connaught elementary school, he wore a rut between his class and the principal’s office. He was always getting tossed out of classes for passing notes, shooting spitballs, pulling ponytails. He called Miss Winchester, the teacher, “Miss Windbag” behind her back. He was promptly kicked off the “Safety Patrol” for heaving snowballs. “The only thing I really liked about school,” confessed Paul, “was sports.”

He was a mighty atom at those, once he fought his way onto the teams. He made the soccer, baseball and hockey teams. He was goalie on a bantam league club that won the city championship, high scorer for “The Ants,” another ice group sponsored by the Kiwanis Club. Later, in Fisher Park High, he caught for the softball team, ran the 100 mile run in eleven seconds. He was the shortest member of the basketball squad, but its high-point player.

And he hustled just as aggressively at making money. He had the knack. One summer, when he was only seven, a gang of workmen dug up the street in front of his house, laying new sewer pipes. He rigged up a lemonade stand and cashed in at a nickel a glass. Next day, he organized a tidy racket, floating a saucer in a bucket of water and inviting the men to pitch pennies for a free drink. The coins that missed—and most did—he fished out and kept.

After that, he shagged bottles for the milkman, mowed lawns in summer, shoveled snow off walks in winter. He swept out a grocery store mornings and afternoons. His newspaper route got to be the biggest in his section of town. One day his dad handed him a bankbook. But the pages remained blank. Paul blew the proceeds on records, records and more records. He stacked his room with platters, his phonograph or radio was always going during his homework, and late into the nights when he was supposed to be asleep.

Because all this time, there was another side to him besides the joker, hustler and athlete. It was a side nobody saw—it was too personal. He knew he had to entertain people. It might have begun when he heard the Anka clan singing around the house, as they all did, especially his Uncle Maurice. The holy chants at St. Elijah’s Orthodox church might have originally stirred what was deep inside him. Paul was an altar boy, then a member of the choir. “Music was everything to me,” he told Annette. And this she could well understand.

Yet high school was one long, confused misery, which brewed plenty of tension at home. “I was so mixed-up,” he said, “I couldn’t seem to settle down to anything. I used to cry at night in bed, wondering why I couldn’t do anything right. It was the worst time of my life.”

Paul was never a great brain in school, but his dad wanted him to be a lawyer. So he dutifully enrolled in the general course. It was a mistake. “I flunked flat and had to repeat my whole first year. I switched to a commercial course, but my report cards were still dismal. The teachers had to call home constantly, with complaints. Dad wanted to help, but when he’d catch me doodling at the piano instead of cracking my books, he’d blow up. ‘Stop wasting your time on those crazy tunes!’ he’d always yell.”

One teacher, who knew about his song writing, liked to pick on him and beat down his dreams. ” ‘Wake up,’ he told me. ‘You’ll never make anything out of that nonsense.’ “

In class, one day, he was reading “Prester John” for a book report. An African village named Blau-Wile-de-Beest-Fontaine kept coming up in the story and it caught in his mind like a witch doctor’s chant. “I began tapping out the rhythm on my desk, when the teacher yelled, ‘Anka—stop that noise!’

“I did, but soon I was drumming it again. The teacher tossed me out of the class.”

“Blau Wile” turned into a song that lodged him in the doghouse, both at school and home—deeper than ever. Nobody dreamed, then, that “Blau Wile” would some day become his first recording.

He’s on his way

The other high spot for Paul Anka was The Bobby Soxers, a local trio he worked up with two pals, Jerry Barbeau and Ray Carriere. The Bobby Soxers were a pretty sharp combo, Paul thought. They all wore identical black, pink and white sweaters, white shoes and black pants . . . but they weren’t identical in height. Paul was still the smallest.

But now he had his heart set on going to New York. Sometimes at four o’clock in the morning, his dad would come home from work and find him waiting up with the eternal plea: “Dad—let me go to New York with my songs. I know they’ll make it. I’ll take care of myself. I’ll call home every day. Only buy me a ticket.”

“Look, son,” his dad would say patiently. “What you want to do is dangerous and wrong. The whole thing’s ridiculous, so let’s stop talking about it.”

And his mother, caught in the middle, said, “Wait a while, Paul.” But Paul couldn’t wait. In the summer of 1956 his Aunt Hortense, who lived in Hollywood, visited in Ottawa. He begged to return to Hollywood with her. To his parents, it seemed safe and they let him go.

In Hollywood, he played and sang his songs for his Uncle Maurice. “I’ve got a few contacts. Bet I can peddle these,” said his uncle. He tried at Capitol and all the big record firms, but couldn’t get a nibble.

“I got awfully impatient . . . you know the way I get,” Paul grinned. Annette grinned back. She knew.

“One day, I flipped through Billboard Magazine and copied down the phone num-bers of all the record companies in Hollywood. The first one I called was Modern Records in Culver City. ‘This is Mister Anka from Canada,’ I said in my deepest voice. ‘I’m in town with some songs. I’d like an appointment.’ “

When Sol and Joe Bahari, the owners, heard him sing “Blau-Wile-de-Beest-Fontaine,” they let him record it and gave him a check for $50. He rushed to the bank and cashed it, dancing on air. “Already,” he said to Annette, “I saw myself on the Ed Sullivan show! But the record didn’t sell. It was an awful bomb.”

Nevertheless, when a reporter from the Journal met him at the plane, back in Ottawa, and that night when he read, “Paul Anka, Local Boy, Records Song,” he finally felt like he was somebody.

That next school term, he merely went through the motions. “Who needs school? I’m on my way!” he’d said.

He was “on his way,” all right—almost to jail! One night, he’d had the Rover Boys, a group of musicians, out to his house. When they had to leave for the show, he begged his mother, “Lend me the car to drive the boys over. I’ll be careful and come right back.” His mother weakened and said “Okay.” He’d taken driving lessons, but he was still too young for a license.

Some time later, the doorbell rang. Two Mounted Police had him with them. The old car had stalled right on the bridge and he’d been desperately trying to push it, when the cops rolled up. His father raged at the news. He was head of a civic group combatting juvenile delinquency. Now, his own son! Paul got off with a lecture and a fine, but he felt he’d broken his dad’s heart.

But being booted out of the Civic Auditorium, a few weeks later, was an even worse blow to his pride. Fats Domino had come to Ottawa with Irvin Feld’s “Show of Stars.” Paul bought a white jacket for the event, determined to have Fats autograph it on the lapel. The police wouldn’t let him near the dressing room, but Paul slipped in and, first thing, bumped into the man who ran the show. “No visitors,” he barked. “Out, fella!”

The man sat down to make a phone call, thinking Paul had left. But when he looked up, the little guy was back—not only getting Fats’ autograph, but having his picture taken with him!

“This time, he grabbed my shoulder and pushed me toward the door, but I shouted at him, ‘I’m Paul Anka. I’m a great singer and song writer. Listen to my songs, please? Take me with you—huh? Paul Anka—remember that name!’

” ‘Yep, I’ll remember. Now, out!’ Mr. Feld told me. And I was out. But I had to have the last word, you know how I am.” Annette nodded, knowingly. “I yelled, ‘Listen, Mr, Feld, one of these days, soon, I’ll be the star of this show!’ “

Finally, his parents realized it was use-less, even cruel, to hold him back any longer. Right before Easter vacation, in 1957, there were more tears and pleas—and, then, his dad surrendered. A few hours later, Paul took the train for New York.

And, amazingly enough. his luck had changed. When he called ABC Paramount, he got an appointment right away. That afternoon, he was standing in Don Costa’s office, shaking strangely but feeling great. Costa pulled back the piano seat, “Well—what have you got?”

All he had was on scraps of paper stuffed in his pocket, but he didn’t need those. The songs were written in his head and heart. He sat down and went into “Tell Me That You Love Me” and “Don’t Gamble With Love.”

“Um-h-m-m—wait here a minute.” Three important looking men, puffing cigars, came back in with Don. “Can we have them again?” They certainly could. “Where’s your father?” one man asked. He said Ottawa, Canada. They put in a call. “Hello . . . Mr. Anka? Your son’s here with us and we love his songs. We’d like to sign him to a recording contract. Can you fly down to New York tomorrow?”

“I nearly ruined everything”

From then on, everything was from Dreamsville. A half finished song that he’d started in Ottawa, sent him winging with his very first platter. That was “Diana,” of course. The day Paul recorded it, he over-slept and had to run all the way up Broadway to the studio without a bit of breakfast. He had a sore throat besides. But in three hours he cut the record which, in a few months, sold three million! Down in Washington, D.C., the same Irvin Feld who’d booted Paul out of the Auditorium, didn’t miss this. He flew to Ottawa, where Paul had returned, and signed him for the “Show of Stars,” just as Paul predicted he would. And when Paul opened in Pittsburgh, who starred on the bill with him? mFats Domino, his idol!

“I felt so good,” Paul told Annette, “that I nearly ruined everything. I was still a little pesty kid.”

On a 90-day break-in bus tour of rock n’ roll shows from coast to coast, he made himself obnoxious to the whole troupe. He sprayed Laverne Baker’s perfume all around the bus, then climbed up in the luggage racks like a monkey and dared them to come get him. He lined the Everly Brothers’ hotel beds with ice cubes, daubed hair grease on telephone receivers, popped out of closets to scare one and all, and generally made himself poison. Each week he needled, “Look. I’m still Number One on the Hit Parade!” Finally, in Omaha, they smeared him with lubricating grease, ripped open a pillow and “tarred and feathered him.”

Maybe you couldn’t expect better of a sixteen-year-old boy fantastically flushed with too much too soon after years of being too little, too young, too nothing! And being laughed at, tossed out, told “Come back when you’re older . . . or bigger . . . or more talented.” Now he was in, and he went so crazy with joy, he got himself lost and mixed-up, He saw, for himself, he needed someone to handle him, or he’d ruin everything. He begged Irvin Feld to be the one. Management isn’t Feld’s business; primarily, he’s a one-nighter king, owns a chain of record shops and a dozen other enterprises as well. He kept doubling Paul’s salary but ducked the personal job. Until one day Paul disappeared. On Thanksgiving day his father called from Ottawa.

“Paul’s here in bed. He won’t eat or sleep, he’s moody all the time. He says he’ll never sing again, unless you manage him.”

“Okay,” Feld sighed, “tell him to come back to New York and I will.” Paul became his first and only client. The boy was so happy, he sat down and at once wrote “You Are My Destiny.” It was no idle title. With Irvin Feld’s help, he breezed right to

the top.

His mom got the house on a hill she’s always dreamed about. His dad has quit night work at the restaurant and handles his public relations.

Someday . . .

“So now you know, Annette, how the moodiness can start if you’re an undersized said at last. And then suggested, “We’d better go in or and, folks will worry.”

They got up and, slowly walking back hand in hand, looked into each other’s eyes. They had to go in to the others, it was only good manners. But they went back feeling close, with a world of new understanding between them.

“It helps when you understand,” Paul said to her, stopping outside the door for a few last moments alone together. “It helps when you’re patient with me like you were today. I love you as much as I can love anybody-now! But I’m growing up all the time, getting surer of myself-and I’ll outgrow the black moods, too. You’ll see. Just keep on being patient with me, Annette . . . please.”

THE END

SEE PAUL IN U.I.’S “THE PRIVATE LIVES ADAM AND EVE.” HE RECORDS FOR ABC-PAR. ANNETTE SINGS ON THE BUENA VISTA LABEL.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE AUGUST 1960

AUDIO BOOK