All The World Salutes Jacqueline Kennedy America’s Newest Star!

No matter which definitions of the word “star” you choose, they all fit Jacqueline Kennedy and Jacqueline Kennedy fits each and every one of them.

On July 2nd, the Associated Press sent the following paragraph to newspapers all across the country: “For the first time in memory, the nation’s top feminine star is not from Hollywood, nor is she an actress. She is, of course, Jacqueline Kennedy. . . . The chic First Lady has supplanted Elizabeth Taylor, Marilyn Monroe and other movie queens as the idol of young girls.”

In the most complete sense of the word, in every way that the dictionary defines it, Jacqueline Kennedy is a star. She radiates beauty, glamour and excitement. She is admired, adored and imitated. Wherever you look, you can see her influence as a wife, as a mother, as First Lady, as a setter of styles and a leader in fashion, as an international beauty. Jacqueline Kennedy’s unique problem, in truth—and the source of many of her fears as America’s newest star—is the fact that she represents a fusion . . . and sometimes a confusion . . . of all these roles.

An expert on birth statistics reports that the name “Jacqueline,” though it’s an old-fashioned name, is fast catching up in popularity with such modern favorites as “Debbie” and “Sandy.” A Beverly Hills hair stylist notes that the girls who used to come in with pictures of Liz Taylor now ask him to make them look “just like Jackie.” A Washington women’s page editor exclaims, “No President’s wife has had such a following in recent history. There are millions of young women who look on Jackie as a model for all the things they’d like to be personally.”

Wherever she goes, Jackie attracts crowds. Like a star, whatever she wears is copied. Like a star, whatever she says—on child upbringing or politics—is discussed and analyzed. And like a star, she lives in a goldfish bowl.

There is one definition of a star that doesn’t appear in any dictionary. It goes something like this: “Star—a person whose private life is always public, whose every word and action may be publicized and criticized.”

This definition fits Jacqueline Kennedy, too.

Walter Winchell, describing a party in his column, reported: “The big topic was Jackie Kennedy’s publicity. . . . ‘I’ll bet,’ said an actress, ‘she’d appreciate a little privacy.’ . . . ‘That’s what you have to give up,’ answered an editor, ‘when you have everything else.’ ”

What few people realize is what criticism and lack of privacy has done to Jackie and the unique perspective it has given her.

Criticism and lack of privacy—“I can see Jackie Kennedy now,” snorts a Republican matron, “right alongside Martha Washington—in a Capri sweater and toreador pants.”

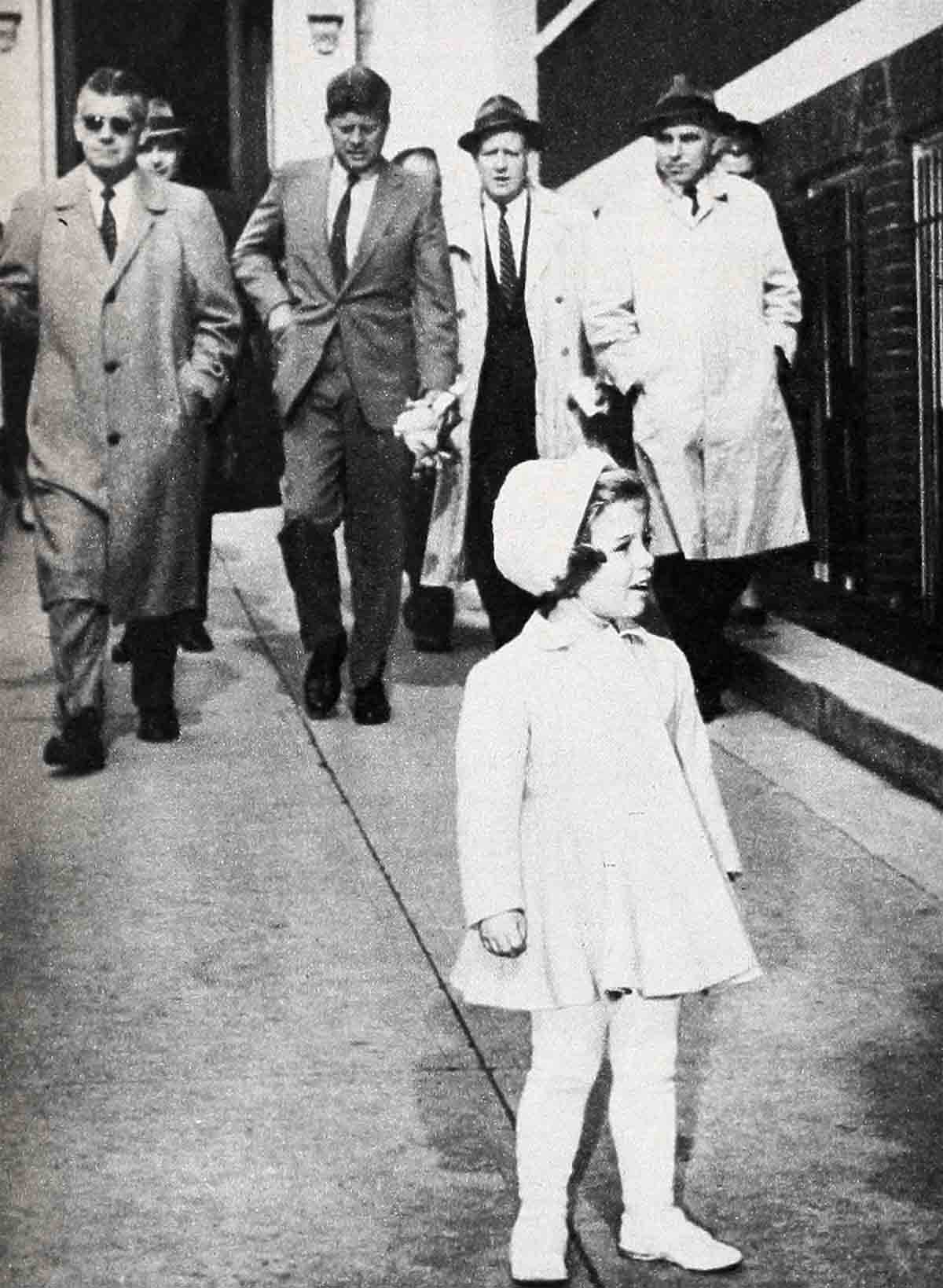

Criticism and lack of privacy—When the First Lady’s daughter, three-year-old Caroline, uses her backyard jungle gym and playground (on the site where President Eisenhower’s putting green once was) for the first time, eager photographers slip through the fence or focus telescopic lenses from outside and record the event for a still more eager public.

Criticism and lack of privacy—When Jacqueline Kennedy is giving birth to John Fitzgerald Jr., a cameraman waits in the hall for her to come out of the delivery room. His flash bulb goes off and Jacqueline gasps, “Oh. no! No! No!”

“A person whose private life is always public, whose every word and action is publicized and criticized”—a description of Jacqueline Kennedy, America’s newest, most glamorous star.

This is not a description that Jacqueline Bouvier ever dreamed would fit her. It’s true that she knew from the first minute she met Jack Kennedy—a tall, handsome, slightly underweight, slightly disheveled young Congressman from Massachusetts—that her world had turned over, that nothing would ever be the same for her again. Yet she could not have guessed then how different it would be.

And if she had guessed, what then? Part of the quality that has attracted so many people to Jacqueline, part of the reason they admire her and want to be like ‘her, is they sense in the glimpses they have had of her that, whatever she thought was ahead, she would somehow have found the strength and the courage to follow her heart.

She married Jack within a year after their meeting and. like every wife. she began immediately to make the many adjustments to her husband’s way of life. They were different in their interests, in their family backgrounds, in so many ways. And in one important way they were very alike—they both wanted very much to complete their marriage, to have a child.

Yet this was not easy for Jacqueline. Her first pregnancy, welcomed with such happiness by both of them, ended in a miscarriage. The following year—the year Jack failed by a whisker to win the nomination for Vice President at the Democratic convention—she lost another child. The stress and strain of the convention had been too much for Jacqueline, and, after an emergency Caesarean, the baby was born dead. And she herself almost died.

Now Jacqueline Kennedy lived under constant fear. Would she ever be able to bear Jack a child?

He changes their roles

In 1957 she was pregnant again. Jack, remembering her cheering presence, her funny little gifts, her tender, loving care all through the harrowing ordeal of his spinal operation, now reversed their roles. He brought her idiotic presents; he did all he could to keep her cheerful and make her forget her fears about the coming birth. He wouldn’t let her take a single step that wasn’t absolutely necessary; he was always at her side.

The day after Thanksgiving, at 8:15 A.M., Jacqueline Kennedy gave birth to a seven-pound, two-ounce baby girl.

The baby was normal and healthy, and she herself was feeling fine. She tried to stay awake all night—just not to miss one second of happiness. She simply hadn’t realized that any one woman could have as much love in her heart as she felt for Jack and for their baby daughter Caroline.

But in 1960, as she awaited the birth of their second child, fear returned to haunt Jacqueline Kennedy—and with good reason. Jack was in the thick of another campaign, this time for the Presidency of the United States, and she just couldn’t sit on the sidelines and be carefully pregnant.

Jack was jumping here and flying there like a grasshopper in a thunder storm. Even when her husband came home, she hardly saw him, so that she complained. “Sometimes when he is at home, he’s so wrapped up in his work that I might as well be in Alaska.” But when he headed for New York City and a giant ticker tape parade, she insisted on going with him. Jack told her “No,” her doctors told her “No.” But how can mere men keep a woman from doing something she’s made up her mind to do? Especially when she said, “If he lost, I’d never forgive myself for not being there to help.”

In France, her husband, introducing himself, said, “I’m the man who accompanied Jackie Kennedy to Paris.”

When the open car on the back of which they were perched reached the financial district in lower Manhattan, it seemed to Jacqueline Kennedy that a million people burst through police lines and swarmed out to greet them. Hands shook her hand, hands slapped her on the back, hands waved wildly in front of her eyes. From the expression on her husband’s face she knew this was the greatest moment in his life. As for herself, she was terrified. In those frightening minutes she must have clung for reassurance to the basic premise on which she’d built her entire marriage: “A wife’s happiness comes in what will make her husband happy.”

“Can you save the baby?”

A few weeks later, while Jack was away, she started having labor pains and was rushed to the hospital. In the ambulance she was gripped by fear. The baby was coming a month ahead of time. Would everything be all right or would . . .?

To the waiting doctor she asked only, “Can you save the baby?”

The doctor did save the baby. Luck, a matter of minutes, and superb medical skill brought John Fitzgerald Kennedy Jr. into the world alive and kicking. Skill, luck, and Jacqueline Kennedy’s courage. As her nine-and-a-half-pound baby was held up for her to see, squalling and squealing his own first campaign speech, she smiled and thanked God.

She was already conscious when the attendants wheeled her out of the delivery room and down the hall. That was when the incident occured that so shook her—when a photographer popped out of a closet and a flash bulb exploded in her face. “Oh, no! No! No!” she gasped weakly. Secret Service men grabbed the camera and destroyed the film.

But the damage had been done! Not physical damage—but psychological. Another invasion of her privacy! Another threat to the happiness and normalcy of her children!

It was episodes like this that made her declare, “It’s not the right life for us. We should be enjoying our children, traveling, having fun.”

The criticism of herself she was getting used to. At first she’d resented it terribly. All through her husband’s Presidential campaign, she’d been held up to ridicule. Why does she cavort around Georgetown in Capri pants? Why does she squander so much money on clothes? Why does her hair always look as if she combs it with a rake?

She acquired a way of handling criticism. “I just don’t let it bother me any more,” she said. “The main thing is my husband’s reaction to me. I dress and wear my hair the way I do because it pleases him.”

But criticism and invasion of privacy, too. That was too much.

The Inauguration was hardly over when a new wave of criticism started. Piddling complaints they were, chipping away at the privacy she valued so highly.

Why didn’t President Kennedy kiss his wife after he took the oath of office? Hundreds of women asked that.

Why does the President always walk ahead of his wife at public functions? Four-hundred letter-writers inquired about that. When this question was passed on to the President he answered, “Jackie will just have to walk faster.”

Why does the Kennedy family make the President’s wife play touch football? Didn’t they play so rough that they once broke her ankle? These were favorite questions, and came in practically every White House mail.

Jacqueline’s answer to these questions was that not only did she not play touch any longer, nor did her husband, but also that on the few occasions when she “volunteered” to play, early in her married life, it was all her own idea. About the broken ankle she had this to say, “Everybody tells the story as though the Kennedys roughed up a young bride. But it wasn’t that way at all. I was running happily along by myself near the sideline when I slipped and fell. There wasn’t a Kennedy within yards.”

The best I can do

But she tried to put criticisms and threats to her privacy out of her mind. She had something far more important to worry about: her new role as the wife of the President. She’d had problems enough just being Mrs. Kennedy, but now, as Mrs. President, her role was much bigger and more difficult.

Her adjustment to it was easier than she’d ever imagined. “I’ll be a wife and mother first, then First Lady.” she declared, and that’s exactly what she proceeded to be.

Often in the middle of a busy day, when Jack was swamped with meetings and conferences, Capitol guards were amazed to look up and see the President and his First Lady strolling down the White House corridors hand in hand. But this shouldn’t have surprised them. Hadn’t Mrs. Kennedy herself said, “I think the best thing I can do is to be a distraction.”

The President’s brother, Attorney General Robert Kennedy, describes his sister-in-law—and her place in his brother’s life—perfectly. “She’s poetical, whimsical, provocative, independent and yet very feminine,” he said. “Jackie has always kept her own identity and been different. That’s important to a woman. What husband wants to come home at night and talk to another version of himself? Jack knows she’ll never greet him with, ‘What’s new in Laos?’ ”

One bit of criticism that Jacqueline went out of her way to counteract was directed not against herself, but at her husband. “It makes me so mad when people say Jack is not warm but cold and calculating,” she sputtered. “He loves to laugh, he is so affectionate with his daughter. She has made him so much happier. A man without a child is incomplete.”

On another occasion she spoke more intimately about what Jack’s love meant to her. “He’s a rock, and I lean on him in everything,” she admitted. “He is so kind. (Ask anyone who works for him!) And he’s never irritable or sulky. He would do anything I wanted or give me anything I wanted.”

The one thing Jack can’t do for her is to turn off that baleful, burning spotlight of publicity that threatens to harm daughter Caroline and little son John Jr. Not that he hasn’t tried.

At Caroline’s third birthday party, held while Jacqueline was still in the hospital after having given birth to John, hundreds of photographers crowded in front of the Kennedy household snapping pictures of the little girl’s guests as each new child arrived. They begged Caroline’s father to be allowed to go inside for “just a few shots.”

The President smiled grimly and replied, “We think she’s been photographed enough. We think she should be retired.”

But how could he stop them from taking Caroline’s picture as she went to and from church? How could he prevent them from using telescopic lens and shooting pictures of Caroline and her little friends through the White House fence the day they first tried out his daughter’s new jungle gym and swings on the lawn?

Even when Caroline’s photograph appeared on the front pages of all the newspapers at the time when there was supposed to be a kidnapping plot against her—and an attempt to assassinate himself—he and his wife had managed to keep the news from her. They had even gone so far as to conceal from Caroline the fact that her father was President of the United States—and that took some doing. And how long could they protect her from publicity, when things like that “drowning” story kept popping into print?

A nation stunned

Caroline Kennedy Rescued From Pool By Capital Matron . . . JFK’s Caroline Saved From Drowning In Pool . . . Caroline Sank Like Stone: these recent front-page headlines stunned America. The story itself aroused sympathy and concern for Caroline and her parents, from everyone who had ever had a small child in the family, or ever loved a darling little girl.

The details were frightening. Caroline was attending the birthday party of three-year-old Ivan Steers, the son of her mother’s step-sister, Mrs. I. Newton Steers Jr., when she decided to go into the pool ahead of the other youngsters, even though she’d been told to wait. Her playmates were still being helped into their bathing suits by their mothers. Caroline, wearing a pink bikini, slipped into the water. Soon she was frolicking and frisking about, holding on to a flutter-board and splashing her feet in the water.

Suddenly, in water four-feet deep—way over her head—she lost her grip on the flutter-board. An eye-witness reported, “Caroline sank like a stone and rested on the bottom.”

What happened next can best be told in the words of the woman who pulled her out. She is Mrs. William Saltonstall, daughter-in-law of United States Senator Saltonstall of Massachusetts, and she is expecting her third child in the early fall. “I was about ten feet from the edge of the pool,” she said. “I ran and jumped over a small wall and leaped into the water. I was fully dressed.”

Mrs. Saltonstall ducked down, grabbed the tiny three-year-old and pulled her up to the edge. Caroline coughed up some water. Then, said Mrs. Saltonstall, “She looked at me, not a bit frightened, and asked why I had my clothes on in the water. I told her that having clothes on in the water was sometimes fun. That’s all that happened.”

A short time later Caroline was back in the pool, unaware of how close she’d come to drowning.

One society reporter with a good memory murmured, “Like daughter, like mother,” and recalled that Caroline’s mother, when she herself was just a child of four, had displayed the same naive and humorous response in the face of danger. She had strayed away from her nurse and gotten lost in Central Park. As she strolled unconcernedly along a park path, a policeman approached her and asked if anything was the matter. “Not with me,” little Jackie answered, “but my nurse is lost!”

They criticized Mrs. Kennedy

The danger to Caroline, of course, had been far more serious, yet some people, as usual, went out of their way to criticize Jacqueline Kennedy. Why did the “drowning” story appear in the papers in the first place, they asked. There were no reporters present. It was strictly a private affair. So why had the episode been publicized? Wasn’t this still another example of the Kennedys’ “use” of Caroline? Of their pushing her into the limelight so that they could bask in the sympathetic publicity?

Furthermore, these people said, what was Caroline doing at a party without her mother? Wasn’t this just one more instance of the First Lady being “too busy” to discharge her maternal obligations? How could you expect anything but trouble for a child when her mother leaves her in the hands of a nurse—a part-time nurse at that? What kind of future would this little girl have if already she was over-publicized and under-loved?

It didn’t matter to these critics that in actuality Mrs. Saltonstall hadn’t even told her own husband about the episode at the pool, and that the Kennedys themselves only learned about it when someone at the birthday party told a friend who in turn leaked the news to the press. It didn’t matter that Caroline’s mother once pledged, “I won’t leave my children with nurses and Secret Service men,” and was trying her best to stick to that promise. It made no difference that Jacqueline had once told a nationwide TV audience, “Some day Caroline is going to have to go to school, and if she is in the papers all the time, that will affect her little classmates, and they will treat her differently.”

How is Jacqueline Kennedy meeting this problem of her children’s over-exposure to publicity? With a woman’s weapons: warmth, concern and love.

“If your husband is President,” she says, “you must spend more time than ever with your children, to make it up to them. . . . My major effort must be devoted to my children. I feel very strongly that if they do not grow up as happy and secure individuals—if Caroline and John turn out badly—nothing that I could accomplish in the public eye would give me satisfaction.”

On her children she’s using the same prescription that once worked so well when her husband was ill. Tender loving care—from both father and mother. She says, “As long as the father is the figure of authority, and the mother provides love and guidance, children have a pretty good chance of turning out all right. The family is the prime unit in society.” She remembers how terribly she missed her own father, the handsome John V. Bouvier 3rd, when he and her mother separated. For years, up to his death, she filled the gap by spending a part of each vacation with him.

This is certainly an effective antidote to destructive publicity, a philosophy of living that will help Jacqueline Kennedy solve her problems as a mother and as a wife. But it is in another area—her activities as First Lady—that the President’s wife is most vulnerable. And there she may be heading for trouble.

She started out with the best of intentions. “I will do everything I can in an official way,” she said, “but no extras like other women. I’ll spend my spare time with my children. It is especially important now that Jack will be so busy.”

“No extras,” she promised, and in the beginning she was able to keep her word to the letter. Subtly but firmly, she effected a quiet revolution in White House entertaining.

The “Jacqueline touch”

Stuffiness and formality went out the window. Grace and ease and comfort came in. At the very first reception given by the President and his First Lady—a party for three hundred executive appointees and their families—the “Jacqueline touch” was apparent.

For the first time in memory, hard drinks were available in the Presidential mansion. And they were plentiful: bourbon, champagne, martinis, Scotch and vodka. Even Cokes for the children.

There was no endless reception line, with guests marching four abreast for a quick Presidential handshake. Jacqueline and Jack greeted people at the door, just like any married couple welcoming visitors to their home.

The hors d’oeuvres were fancier than ever, and there was more than enough for everyone.

Reporters were encouraged to mingle with the guests.

There were lots of ashtrays every place, the most revolutionary White House change of all.

At the second White House wingding of the season—a reception for ambassadors and their wives—Mme. Hervé Alphand, the wife of the French Ambassador, took one look at the flowers all over the place—lilies of the valley, tulips, anemones and apple blossoms—and paid her hostess the highest possible compliment. “Why, they look like they had been arranged by a human hand instead of a florist,” she said.

The Peruvian Ambassador Fernando Berckemeyer seemed to speak for everyone when he declared, “I’ve never had so much fun in the White House.” It might have been the sight of “assistant hostess” Caroline Kennedy perched on the stairs and tapping her foot to the Marine Band rendition of “Old MacDonald Had a Farm” that made him say this. But more likely it was the fact that his hostess, whom he’d known since girlhood, greeted him unceremoniously with a question. “Aren’t you going to kiss me?”

By the time the third big White House shindig was over—an affair where Congressmen were “introduced” to Cabinet members—the verdict was in. Jacqueline was the most imaginative and exciting hostess Washington had ever known.

In a sleeveless, floor-length sheath of pink and white straw lace, set off by a single piece of jewelry—a feather-shaped diamond clip in her bouffant hair—she had danced, first with her husband and then with almost everyone of the four-hundred and fifty VIPs present. It was like a high school prom, with one fellow after another cutting in on her. Even the few who didn’t get to dance with her joined in the acclaim, “She’s divine.”

Trouble started, however, when Jacqueline and her husband left Washington and hit the “diplomatic” trail. Of course, they had to leave the children behind, at first for a few days, later for weeks on end. That bothered Mrs. Kennedy, she missed them. And despite her early hopes that it wouldn’t be so, there was a conflict between her duties as a First Lady and as a mother.

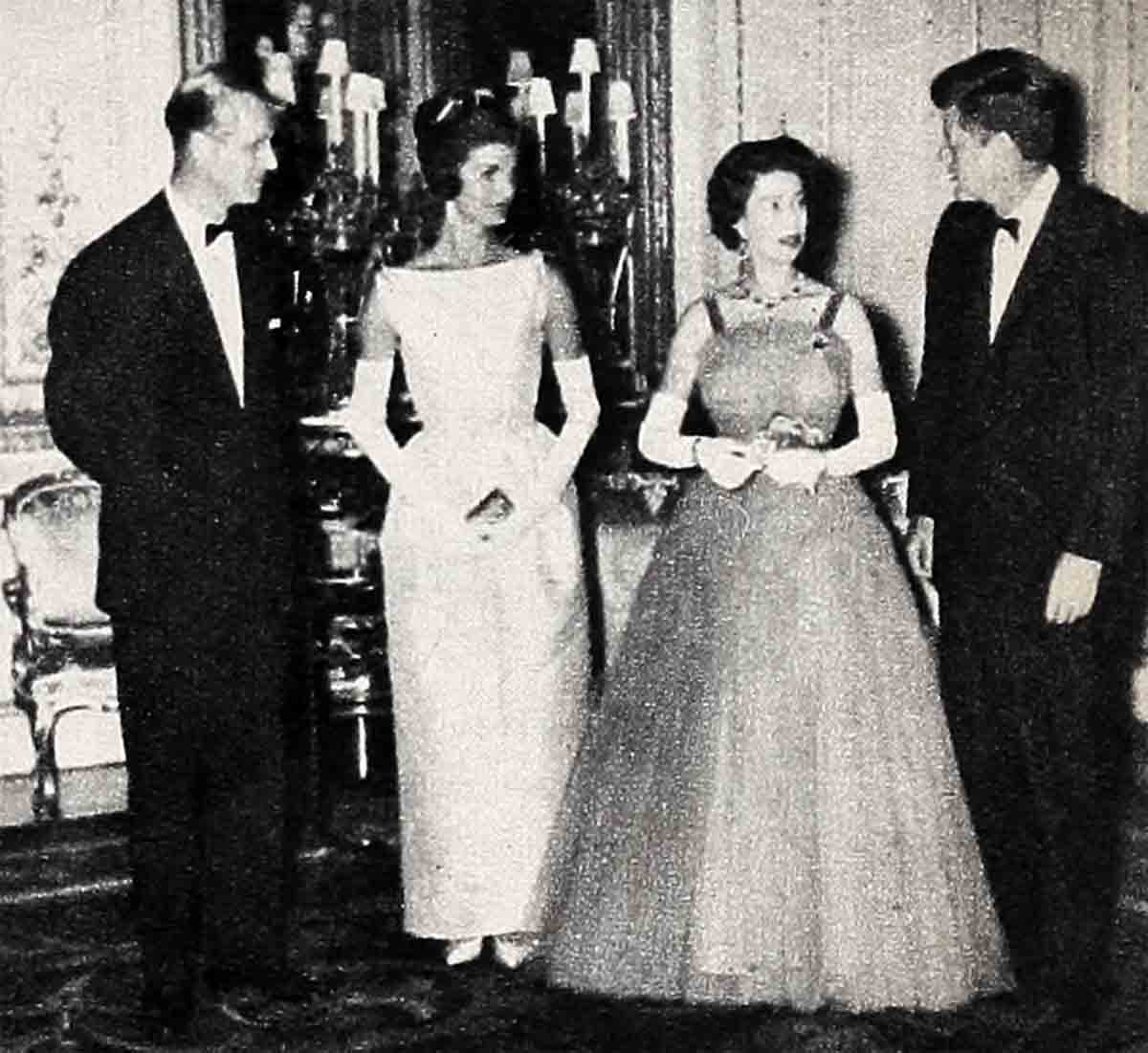

There was another possible conflict—more hidden but there just the same. She had become a star, a celebrity, an attraction in her own right. She was no pale reflection of her dazzling husband. And as Hollywood discovered long ago, two stars in the same family can mean trouble. In Canada, for instance, there was a formal state dinner for the Kennedys, during which Jack made a key foreign policy speech. Yet what did the papers concentrate on the next day? “Every head snapped around as though at parade-ground command, to admire the entrance of Jacqueline Kennedy in her pure white sheath dress.”

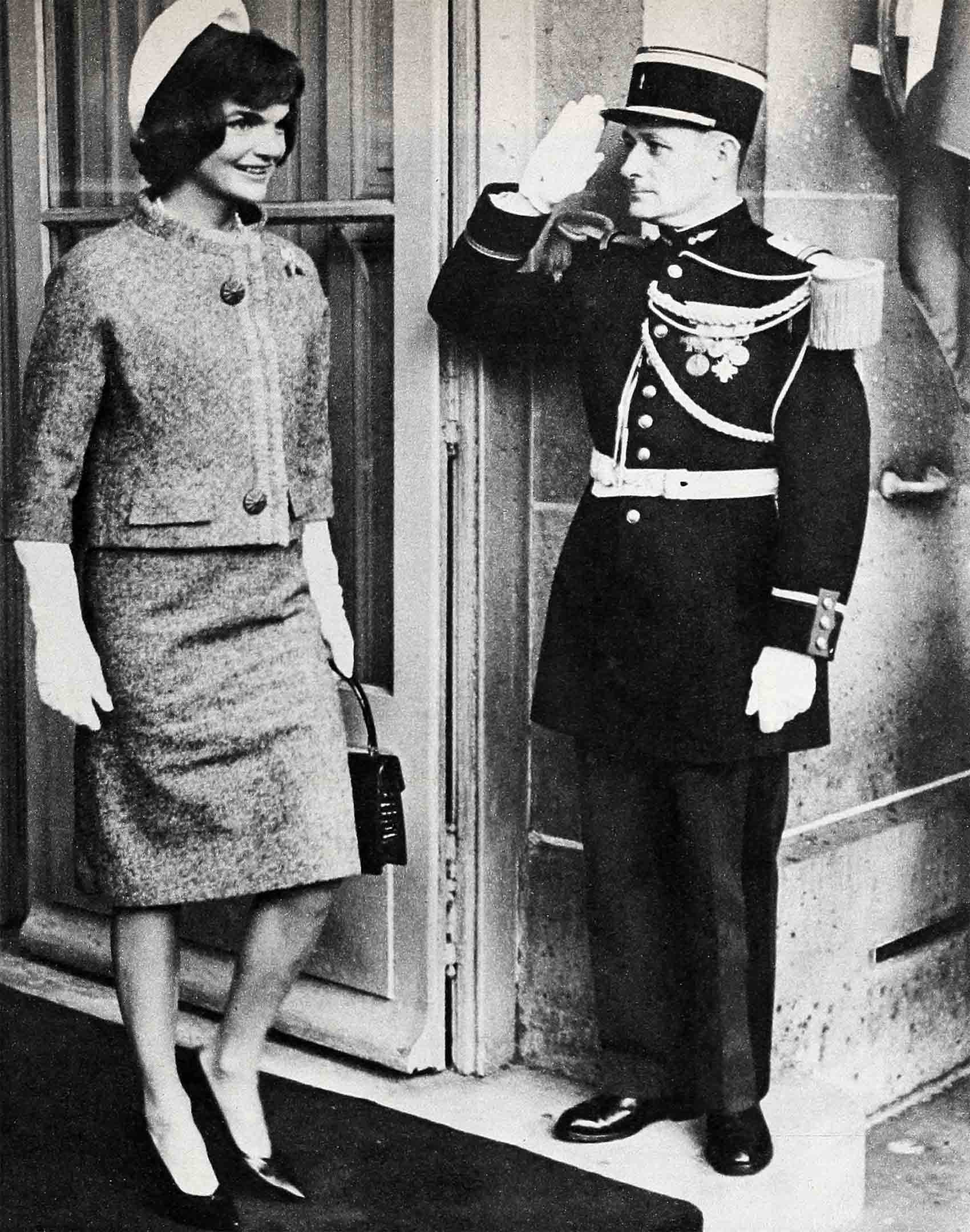

In Paris, it was the same thing. Actually, Jacqueline was somewhat frightened by their impending visit to the French capital. It was a city she knew well. She had studied art and languages at the Sorbonne as a girl, and she remembers herself as a “chubby little thing eating pastries and studying with inky fingers half the night.”

She had loved Paris. But for her, Paris had definitely not been the City of Love. “Mostly the boys I knew were beetlebrowed intellectual types who’d discuss very serious things with me,” she recalls. “Nothing romantic at all.”

Now she was going back with the man she loved, and everything must be perfect. A month in advance of their visit, she arranged for the services of Alexandre, the leading hairdresser of Paris, and of Harriet Hubbard Ayer, the famous cosmetics house. Carefully she selected an all American wardrobe for herself, for one constant source of adverse criticism against her was that she usually favored French clothes.

Her actual arrival in Paris at Jack’s side was more wonderful than anything she’d ever dreamed. As the Presidential car rolled slowly through the packed streets, a one-hundred-and-one-gun salute shook the city, only “to be drowned out,” as one paper put it, “by the cry ‘Vive Jacqueline!’ ”

At a small ceremonial luncheon with de Gaulle she sat at his right and melted his glacial reserve with her school-girl French—just as previously in Washington she had been the only one ever to make frozen-faced Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko smile. As observers watched the Head of State of France and the First Lady of the United States chatting and laughing together, they recalled de Gaulle’s statement the previous year during his trip to Washington, D.C. “If there were anything I could take back to France with me.” he had said, “it would be Mrs. Kennedy.”

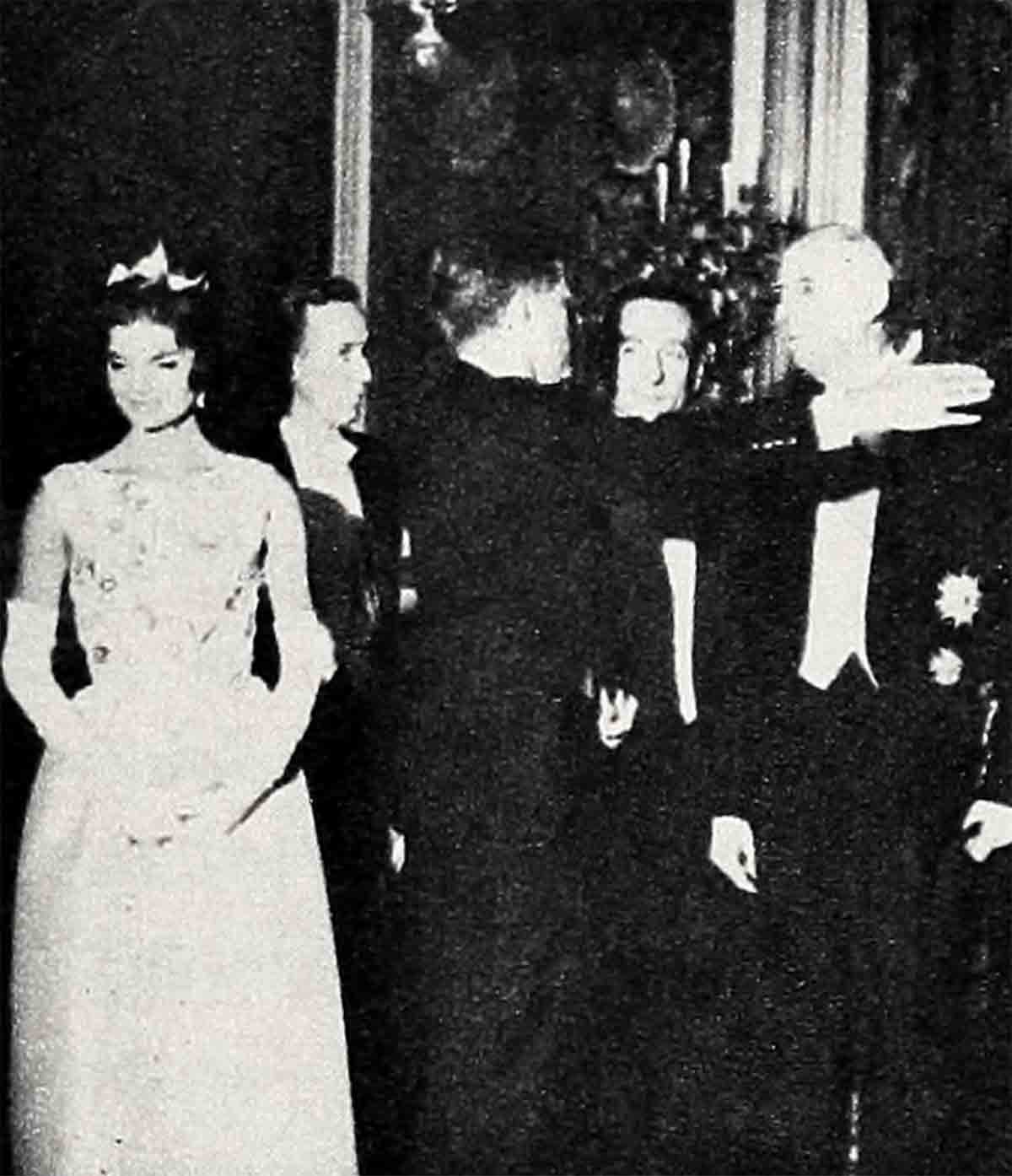

That first night in Paris, the Kennedys went to a formal reception, where more than two thousand of the cream of Parisian politics and high society showed up, mainly to see the American First Lady. But none of their “oohs” and “ahs” when they saw her—so beautiful in her narrow, pink-and-white straw-lace gown, her hair coiffed in a swooping 14th century hairdo with a false topknot—affected her as deeply as had her husband’s reaction, earlier that evening when she’d first walked out of her bedroom at the Palais des Affaires Etrangéres. Walked out and stood there.

Jack had taken one look at her and whispered, “Well! I’m dazzled.” That was the high point of her visit to Paris.

But her “official” triumph was the night they went to the Palace of Versailles for a banquet in the Hall of Mirrors. On that occasion, as a gesture of thanks to the French public, she switched from her allAmerican wardrobe to a French creation by the Parisian designer, Hubert de Givenchy. Her gown was fashioned of white silk with a bell-shaped skirt and a bodice embroidered all over with multicolored flowers. Her matching coat was of heavy white silk. Her head was set off by a tambourine-shaped hair piece set with five diamond pins. When she told Alexandre that the jewels were “too much,” the hair stylist answered, “Make an effort, Madame, make an effort!”

The effort was worth it. The following day the French papers were filled with rhapsodic prose in describing her appearance and impact the previous evening. “Charmante! . . . Ravissante! . . . tres jolie! . . . la belle Zhakee!”they raved.

How did her husband take all this? With his usual sense of humor—that was the important thing. As long as they could laugh at each other, and at the things said about them, everything would be all right. He reacted the same way he had when he’d once heard a radio comedian quip, “Good Night, Mrs. Kennedy, wherever you are!” With laughter.

At a press conference during their stay in France he begun wryly, but with a twinkle in his eye, “I do not think it altogether inappropriate for me to introduce myself. I am the man who accompanied Jacqueline Kennedy to Paris.”

With laughter and love . . .

After the Kennedys’ visit to France. Time Magazine jumped on the bandwagon of the ever-increasing number of publications hailing Jacqueline as a star. Where the Polish magazine Swiat had previously lauded her for the new “tone and style” she had set for the “epochal ’60’s,” Time now declared, “The U.S. had a queen—and not from Hollywood.”

As a star and First Lady and mother and wife, Jacqueline Kennedy has her fears and her problems. But she and her husband are conquering and solving them with patience and humor.

And with love.

THE END

—BY JIM HOFFMAN

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1961

zoritoler imol

3 Ağustos 2023you are really a good webmaster. The site loading speed is amazing. It seems that you are doing any unique trick. In addition, The contents are masterpiece. you have done a fantastic job on this topic!