We Find Jackie’s Forgotten Family

I had come to France and the village of Pont Saint Esprit—five hundred miles to the south of Paris-to track down and interview any members of Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy’s family who still lived there.

Fortunately, right off, I ran into a fellow named Aristide, who would soon lead me to them. And so a word about Aristide first. He’s a young fellow, barely twenty, a student at a nearby university. He is tall, dark, moody, with bushy black hair and large, dark-brown inquiring eyes. And he was extraordinarily interested in my visit to the 26 village of Pont Saint Esprit for Photoplay.

“Why do you want to see the Bouviers?” he asked—quite directly.

“To find out,” I said, “if Jacqueline has ever visited them—or if not, would they like her to visit them.”

“No,” said the young man. “Jacqueline Kennedy has never visited this village— although there is a woman here, an old lady, who will tell you that she has. I will introduce you to her, but she is quite mistaken, She is always making up stories, and her story about Jacqueline Kennedy is this: that one day about ten years ago—a cold winter’s day—a car pulled up t o the village square, the Place de la Republique. A young girl got out of the car, a very pretty girl, very chic, an obvious foreigner, and walked around for a little while. She spoke to no one. She sought out no one. She simply walked. And looked. And then she got back into her car and drove away. That, swears the old woman, was Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy. . . . But as I said, the woman is quite . . . well, prone to inventing little stories. So no—to answer your first question—Jacqueline Kennedy has never visited our village. And as for relatives—your second point—would they like her to come? Of course they would. But there are some of them who think that she will never come.”

“Why not?” I asked.

“Because,” said Aristide, “she has had the opportunity to come here before—but never has. For instance, only this last summer she was visiting in Italy, not very far from here at all, for two weeks she was there, but she did not come here. . . . And for instance, she wanted no publicity about her family in the summer of 1961, at the time of the President’s State visit to France. She wanted no one to know that she would finally meet with one of her cousins in Paris. The French reporters who had arranged this visit were disappointed—but knowing how important it was to Danielle, they agreed to step out of the picture.”

“Who,” I asked, “is Danielle?”

“Who, you should ask,” said Aristide, “was Danielle.”

He paused for a long moment.

“No,” he said then, “I cannot tell you that story. It is too personal. It must come from the family themselves. It is a tragic story. There are those in Pont Saint Esprit who say that it is the story of a great comedy that ended in great tragedy. But you will hear it for yourself in time. For now,” he said, “let me show you some proof that has been gathered which makes it indisputable that Mrs. Kennedy is related to the Bouviers of Pont Saint Esprit. And then we will be off to meet the cousins.” The proof was all there, in a local library, gathered from dusty archives which Aristide and a few others had combed through back in the summer of 1960, a few days after John F. Kennedy had been nominated to run for President of the United States.

The proof was this: that a Michel Bouvier had been born in Pont Saint Esprit in the year 1793; that he had left Pont Saint Esprit for Philadelphia one day in 1815; that he had married in Philadelphia and had had ten children—Jeannette, Lizzie, Eustache, Emma, Therese, Louise, Jean, Albert, Martin and Michel; that the younger Michel had grown up and married a young lady whose maiden name was Vernou, also French; that they had had a son whom they’d named John Vernou Bouvier; that John had in time married a young woman named Janet Lee and that they had had two daughters—Lee Bouvier and Jacqueline Bouvier.

“See here,” said Aristide then, pointing to some clippings from local newspapers of July 1960. “See how excited the village and Jacqueline’s relatives were about the forthcoming election. See the enthusiasm that gripped this little place where practically nothing of consequence happens.”

He handed me the clippings. They read, in part: “Pont Saint Esprit must be proud today of its tie with Mrs. John F. Kennedy and must wish that in November her husband is victorious—her husband, whom we are assured is a great friend of France.

“Mrs. John Kennedy, nee Jacqueline Bouvier, is, as everyone knows, of French origin and more precisely of local origin. The success of her great-grandfather who emigrated to the U.S. and amassed a vast fortune in veneers and paints is a fact with which most of us are familiar and pleased. The success of her husband, the young and dynamic American senator, would be wonderful in that Mme. Kennedy would certainly make a stop here on her next trip to France.

“One of the most interested parties in all this activity is our aged Mile. Baudichon, the closest of all living relatives to Mme. Kennedy. Mlle. Baudichon has one hope for her eighty-third year; that is, to see one day in Pont Saint Esprit her cousin from the United States, who will come visit the ancestral home and the cemetery alongside that home and thus be reunited for a little while at least with her family in France, both living and deceased.”

I handed the clippings back to Aristide.

“Mlle. Baudichon,” he said, “has since died.” He shrugged. “As for Danielle—” he started to say. But again he shook his head and said, “No. That is for the family to tell. In just a little while. Though first . . .” He began to walk toward the door of the tiny office along with me. “Though first I must stop and discuss something with Marie, my fiancee. You must come with me. It will only take a minute. And I should like you to meet my fiancee. She is much more pleasant than I.”

Her visit—a feast day!

Marie smiled merrily when we were introduced. And after her “private” talk with Aristide—carried on in a loud patois—she turned to us and said, “I, for one, look forward very much to the day when Jacqueline Kennedy will come visit us here at Pont Saint Esprit!”

“You think she will, then?” I asked.

“But of course,” said Marie. “And it will be a great feast, the day she comes to visit us, Jacqueline Kennedy—for those who are her cousins and those who are her townspeople. And what a celebration there will be here!”

“What kind of celebration,” I asked, “do you think would be planned for her?”

“Something typically Provencal, typical of this area in which we live,” said Marie.

“We are an outdoor people, as you can see, and most of the celebration will be in the streets. There will be the traditional dancing. The Farandole—a wonderful dance. With all the young boys and girls in the village holding hands and twisting, like snakes, through the streets. And with traditional music, of course. The fifres and the tambourines.

“And,” Marie went on, “there will be also the free run of the bulls for Mme. Kennedy. That is called here La Course Libre. That is very traditional here. Every week in the summer and the good weather. With ribbons attached to the horns of the bulls and everyone chasing after the animals to see if they can tear off a ribbon. A scene of true and gay hysteria. Something, I think, that will please Mme. Kennedy very much—and also the little Caroline, should she bring her along.

“And, too, there will of course be a speech of welcome by Monsieur Leandri, our very fine mayor.

“And, of course, our handsome French actor, Jean-Louis Trintignant, will be here from Paris for the occasion. This may come as a surprise to Mrs. Kennedy, but Trintignant is related to her—a distant cousin.”

“Enough of this,” Aristide said, interrupting the girl. “We must be going. We have more to do than to listen to your transcendental suppositions.”

“Poof—you,” said Marie, laughing again. Then she threw me a wink and she said: “Sometimes I wonder why I am marrying this boy.”

And a moment later—Marie’s continued laughter behind us—he and I were off.

The walk to the house of Jacqueline Kennedy’s cousins—from one end of the village to the other—would ordinarily have taken five minutes. But with Aristide as my guide, it lasted more than an hour.

He took me first through the ancient quarter of the village, where the streets are no more than eight or nine feet wide, and the houses pasted one alongside the other—“because, you see, in the very old days, when the winds blew heavy from the north and the enemies came heavy from the south, it was important for people to be as close to one another as possible, for their protection, and comfort and peace of mind.”

He took me next to the Monument aux Morts, the monument to the dead, located at the foot of the main thoroughfare of the village, called somewhat extravagantly the Boulevard Gambetta—“this monument was built to honor those who died in all of the wars in which France has fought. And to honor those men and women and children who died in the American air raid of August 22, 1944. The Americans were out to destroy our bridge. Instead, only one bomb landed on the bridge and more than a dozen houses were blown up. You see there, that name on the plaque? Antoine Bouvier? He was a cousin of Mme. Kennedy. He was in one of those houses at the time of the bombing.”

He took me then to see the city’s ancient fortress, alongside the River Rhone—“this, too, was hit by the American bombs. And good thing, too. For the Nazis were quartered here then. The terrible Nazis.”

We walked along the quai which borders the Rhone and stopped to look at the magnificent and ancient bridge which spans the river.

“Your Mrs. Kennedy,” said Aristide, “she might be interested in this little story, being a religious woman. The story is that when the bridge was being built, back in the Twelfth Century, there was one man who worked harder on its construction than any other. He was a stranger. No one knew who he was, nor from where he had come. No one could understand why, when the construction of the bridge was completed, he refused any wages and, instead, simply disappeared. Then one night one of the workers on the bridge had a dream. He dreamed he saw the mysterious man who had toiled so hard and left so quietly. He dreamed that the man had said to him, very simply, these five words: ‘I am the Holy Ghost.’ And thus the bridge was named, as was the village: ‘The Bridge of the Holy Ghost’—Pont Saint Esprit.”

We continued walking.

And then, pointing ot a small house we had just reached, he said, “This is it, your destination. No. 6, Quai de Luynes. It is in this house that Jacqueline’s true cousin Mme. Paulette Bouvier-Souquet lives. With her husband, Raymond. And her children, Mireille and the baby Jacques. They are very friendly people. They are nice people. Their house, you can see, is most modest. But their hearts are large. Come, let us go meet them. And let us see what you can learn about them and their relative in the United States. . . .”

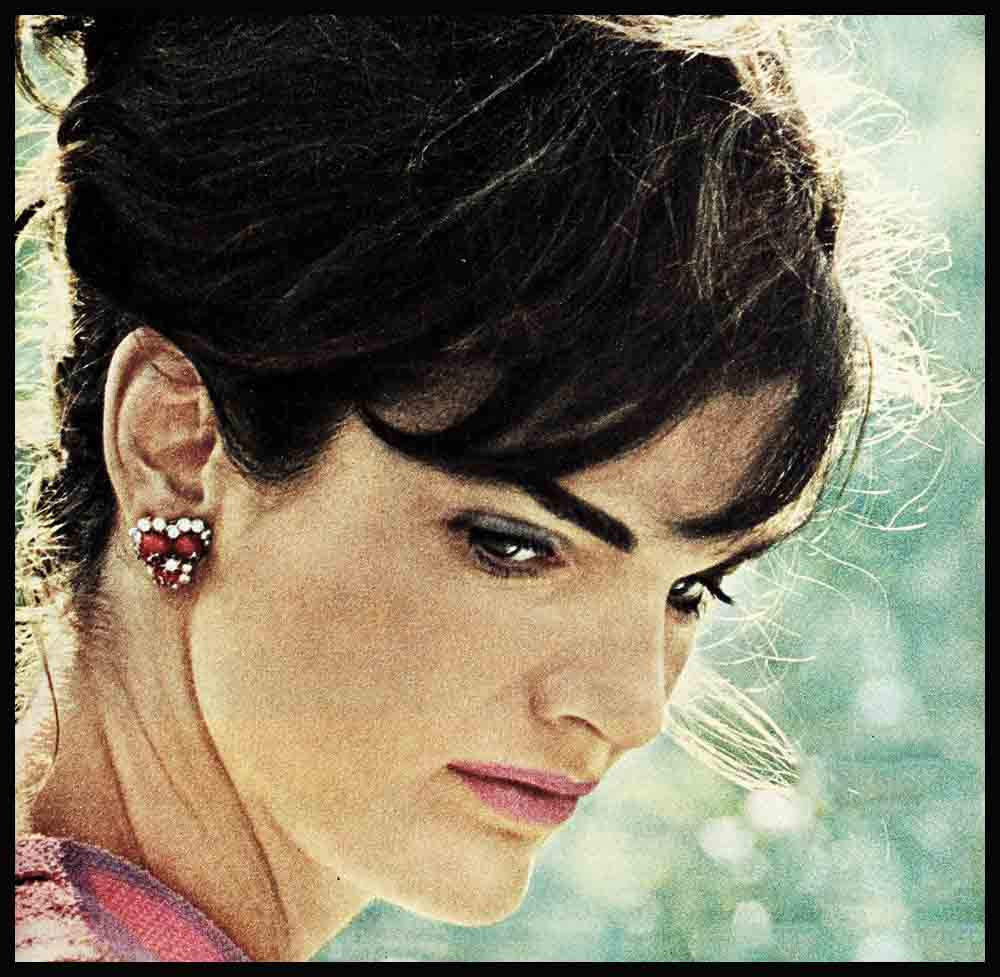

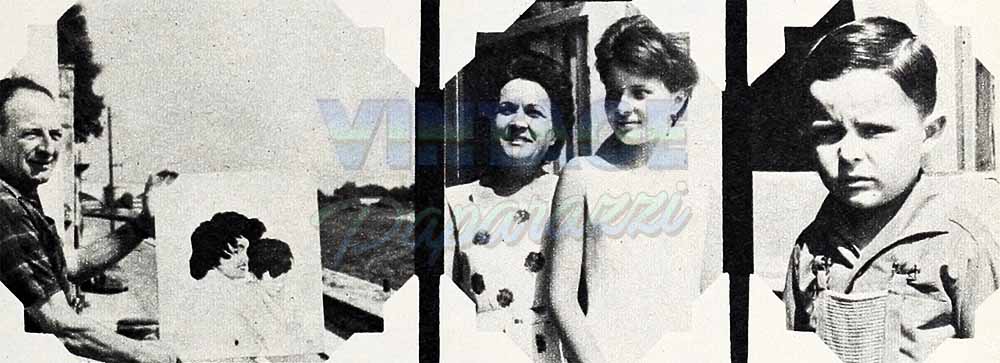

I could see it immediately—the striking family resemblance to Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy in the faces of Mme. Bouvier-Souquet and her thirteen-year-old daughter, Mireille. Their eyes were the same as Jacqueline’s—hazel, rather widely separated. The smiles were Jacqueline’s—expansive, warm. The shape of the faces. The coloring of the hair. The general quiet beauty. All were the same, as with Jacqueline.

I spoke a few sentences of greeting, with the woman and her daughter. But not for long. Because, as I was soon to learn, this was a typically French family where the husband and father did most of the talking. And Raymond Souquet was obviously a good-natured man who enjoyed to talk.

“Here,” he began, “first I prepare you a pastis, a traditional drink.” Then: “Now, about our cousin, Jacqueline Kennedy. You must say to your readers that we all love her very much, the entire Bouvier family. And that while we are disappointed that she has never come to visit us, we hope that she some day will.

“So far, our relations with cousin Jacqueline have been most cordial. For instance, as you look around the room here, you can most certainly see that I am a painter. I am, too, a man of business. You might tell your readers if you would be so kind that I am beginning an involvement in the construction business and also in the travel business—and that if any of them would like a house built here in the South of France, or would perhaps like to travel here and have hotel accommodations arranged for them, that I—Raymond Souquet—would be very happy to make such arrangements for them. They will learn that I am industrious, and honest, and very eager to serve.

“But, aside from my business affairs, basically, in my heart of hearts, I am a man who enjoys to paint. Look on the wall here—this is an ancient sea battle I have ‘ just completed. Very detailed work. Very I difficult. And over here—this is a pride and joy of mine, a likeness of our cousin Jacqueline holding her new child, the baby John, in her arms. Does that painting not give the impression of a Madonna with child? You think so? Thank you. For that is what I tried very hard to capture in our cousin Jacqueline; since she does have, I think, the beauty of a Madonna.

“But even more important, look here, I at this painting. You will see that it is a painting of our bridge here at Pont Saint Esprit. You will notice, perhaps, that it is painted on a very special piece of wood. I say special wood because it comes from a bed in the old Bouvier farmhouse—or mas, as we call such houses here in the South of France. In fact, it is from the very bed on which cousin Jacqueline’s great-grandfather, Michel, was born. I have made two such paintings of our bridge. One is the one you now see. The other perhaps today hangs in your White House in the capitol of Washington, D.C. At any rate, I sent that painting to Mme. Kennedy just last year. And may I show you the very nice letter which she sent me in return. Here it is. I will read it for you.

And he read: “The White House, Washington, 11 May, 1961.

“Dear Monsieur,

“Mme. Kennedy has instructed me to thank you for your pretty present. She was very touched by your kind attention, your painting of this charming landscape in the town of Pont Saint Esprit. With all our thanks, dear Monsieur, and our very best wishes.”

“That is the letter, then. From Jacqueline Kennedy. Or I should say from Leticia Baldridge, the social secretary to Mme. Kennedy, since it was she herself who signed it. But she is herself a very important woman and very close to Cousin Jacqueline—is she not? And so, in a way, it is the same thing—is it not?

“It is a shame that we did not get to meet cousin Jacqueline as we had all hoped to, last August, when she and her husband the President were in Paris visiting with General de Gaulle. But the awful tragedy prevented that. The awful tragedy of our poor young Danielle.”

The story which we then heard was this: Danielle was the daughter of Mrs. Souquet’s brother, Marcel. She was eighteen years old. A most beautiful girl. And lively. Very lively. Who liked everything about America, and who was so thrilled when she learned that she was related by blood to the First Lady of all America. Danielle would say, over and over. “Oh, if only some day I could meet my cousin Jacqueline and she would say to me, ‘Why don’t you come to live in the United States for a while Danielle?’ Oh, how happy I would be then!” She loved the United States, Danielle did, this girl who had never travelled more than thirty kilometers from her home. She loved her cousin, too, the cousin whom she had never met—Jacqueline. She loved life, Danielle did. Everything she loved. Everything.

When the townspeople of Pont Saint Esprit heard that Jacqueline Kennedy and the President were coming to France in 1961, they thought how nice it would be if they took a day from their trip to come visit the village. They contacted everyone possible in Paris. The ambassador. Friends of the ambassador. Friends of their friends.

But to no avail, it seemed. For their letters were never answered.

But then two radio reporters in Paris got wind of what the villagers were trying to do. And they volunteered to help. The reporters explained first that it would be very difficult for the President of the United States and his wife to travel all the way from Paris for a day, that their schedule was very strict. But, they said, there was a very good possibility that if Mme. Kennedy heard about how anxious her family was to meet her, she might perhaps meet them for a little while in Paris.

For days after that, there was no word. Skeptics in the town laughed at the idea. They said, “She will never say yes. Can’t you just see her posing with the little country cousins from the little town in the south?” They laughed. They laughed. And every day that passed, with no word from Paris, their laughter seemed to grow.

But then, on the day of the Kennedys’ arrival in Paris, the two radio reporters pulled up to Marcel’s house.

“She will see you,” they said, excitedly. “Tomorrow, for a few minutes, in Paris, while her husband is conferring with de Gaulle. She has stressed that she wants no pictures, no publicity. This is no good for us—after all, for us it would have been a great story. But if it makes you all happy, then we feel that it is worthwhile.”

Needless to say, Danielle was the happiest of all the Bouviers. No one who was around will ever forget watching her pack that night for her trip to Paris and to meet her cousin Jacqueline—the delight, the joy, he anticipation, as she folded the new dress she would wear for the occasion. And how she wrapped in very fine tissue paper the little gift which she had bought to bring as a gift to cousin Jacqueline’s little daughter—a tiny toy nightingale.

Danielle and her father were scheduled to leave for Paris very early the next morning, in the car with the two reporters.

Said Monsieur Souquet, continuing:

“Because there was not enough room in the car, my wife and I—the only other two who would meet cousin Jacqueline—left for Paris by train the previous night. Hurriedly, we packed. Hurriedly, we departed. Very tired, very tired, we arrived in Paris the following morning. Only to find out the news. That the car in which Danielle and the others had heen riding had crashed into a tree. That Danielle had been killed. Instantly. That the others had all escaped serious injury. But that Danielle—only eighteen—was dead.

“Sadly, right from the station where we heard the news, my wife and I returned to Pont Saint Esprit. The next day, very nicely, we received this message from cousin Jacqueline. Here. This is it. I will read it to you, if you will permit me.”

And he read aloud: “I am very sorry about the bereavement that has struck you and please share my most sincere condolences with every member of your family. (signed) Jacqueline Kennedy.” “And this here,” he went on, “this is the little letter which I sent to cousin Jacqueline in return.”

He read: “On behalf of the entire Bouvier family, I was touched by your message. We thank you with all our hearts for the meeting you accepted. for which we had so feverishly prepared, and which would have filled us with joy. Danielle had prepared so hard that she might he of that journey. Her joy was very great and at the church where she had gone to pray just before leaving on the journey, she had kissed her father and said, ‘This is the finest day of my life.’ Unfortunately, that day stopped at dawn. (signed) Raymond Souquet.”

“And so that is how it went that time, last August. With Danielle.”

But his voice seemed to choke up now, and he was finding it hard to go on. He lifted, instead, the bottle of anis.

“A little more,” he asked me, “to drink?”

“No thank you,” I said.

“Aristide? You? A drink?”

“No.”

“Paulette?”

“No.”

“Mireille?”

“No, Papa.”

Raymond Souquet placed the bottle back on the table.

“What a country France is becoming,” he said, “if everybody—including myself —begins to turn down a glass of good pastis.”

And he tried very hard to smile.

It was a little while later. I stood with Aristide at the small railroad station of Pont Saint Esprit, waiting for the train that would take me back to Paris.

“If Mrs. Kennedy does come to this village one day, Aristide,” I asked, “is there anything in particular that you personally would like to say to the First Lady of the United States?”

He thought for a moment.

And then he said: “Yes—yes—I would tell her, ‘To really know this village, Mme. Kennedy, slip away from me and all the rest of the crowd for a moment, if you can. And go for a while down to the river. Alone. And stand there and gaze at the Rhone. And breathe in its particular scent. Its lovely scent. Plus the scents of the mistral—the wind from the north—and the platan trees all around you, and the sun above you and the vineyards to the south. Breathe in deeply, Mme. Kennedy, these scents. For these are the scents of your past . . .’

“And then I would say to her: ‘Now look up from the river. And turn and stare right behind you. At the ancient buildings that still stand there. At the people who will be looking at you through the windows of those buildings. And—and study hard those buildings and the faces of those people. And as you do, dig your feet hard into the earth on which you are standing. And from all this, Mme. Kennedy, I think that you will perhaps discover about yourself a little something that you have never known. And that—even to your surprise—you will be an even happier woman for having made these discoveries, at last.”

We waited in silence, after that, for the approaching train to pull into the little station of Pont Saint Esprit.

DOUG BREWER

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MAY 1963