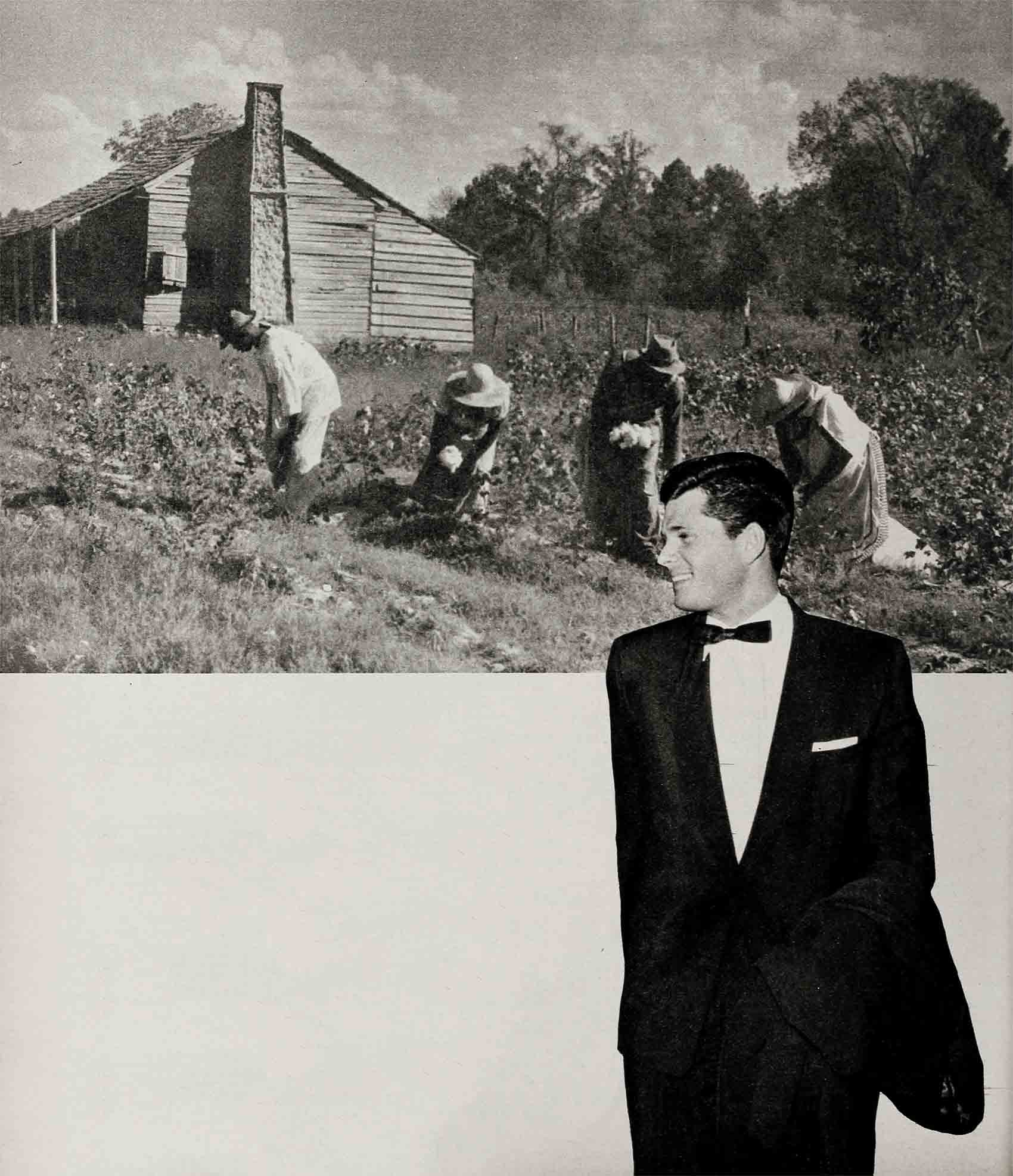

How They Got To Hollywood From No Place—Dewey Martin & Rita Moreno

DEWEY MARTIN tells his story: The Poor Kid From The South

You know, a few years ago when I made my first picture, I got more money at one time than I’d ever had in my life. So I sat my mom down one evening and asked what she wanted more than anything else. “You name it, Mom,” I said, “I’ll get it for you.”

Mom looked at me as though I were still a little child. She thought for a minute and then said, “People that are happy don’t want anything, but to stay happy. Thank you for offering, son, but I don’t need to be any more pleased than I am.”

That’s the way my mom is. But she has good reason to be happy now. So do I, I think. Mom and I didn’t always have it this easy. Not by a long, long shot. There’s one thing you ought to know first. I’m thirty-four years old and I’ve never been so happy in my life.

People ask me, is that because I’ve married Peggy Lee?

Well, yes and no.

I say yes, because as a man I’m experiencing the sensational feeling of having found a girl like Peggy, falling in love with her and winning her as my wife.

To be in love twenty-four hours a day, to know that Peggy loves me, well, that’s—what word do you use? Sensational? Exciting? There’s no word for it that I know.

But there’s a separate kind of happiness I’ve found. It’s something I had to make for myself and I’m going to give it to my marriage. And for my money its the most important gift a man has to give to a woman.

It is not being afraid of life.

Now that was something I had to learn for myself. It had to be part of me before I married Peggy.

You’ve got to have Hope

I’ve never really talked about my life before. But, maybe now it would be a good thing for me.

I’ll tell you what I’ve learned: Hope. You’ve got to have hope.

I don’t remember Dad very well. I was seven when he passed away. He was a musician and had a cowboy band that used to play at dances around Katemcy, Texas, where I was born. Our family, (I had an older brother) was pretty well known in that section. My grandfather was a country doctor.

The only thing I remember about my dad was that he had a lot of friends and let me help him make beer. You couldn’t buy beer then, during prohibition. Most Texans made their own. I guess Dad was a good amateur brewer because every so often he’d make a big mixture in a vat. My job was to start the beer out of the vat through a siphon hose for each bottle and I can remember everybody laughing when I’d get a mouthful of home brew.

Calamity

Dad died in 1930. Mom tried for months to keep us going on what she could earn doing laundries, and as a cleaning woman. When she saw it was useless she decided to go to Oklahoma.

My cousin came down to Texas with a trailer. We loaded all our belongings on it. Chairs, tables, clothes, dishes and Mom’s most cherished possession, a big, bulky, table radio.

On the way to my cousin’s farm in Oklahoma we took a detour around a washed-out road. Half-way ‘through the by-pass, the car hit a sudden dip and suddenly, before we could do anything, the trailer turned over, toppling everything we owned into the biggest mud-hole I’ve ever seen. Our bundles of clothes sank like rocks.

The furniture took longer to sink and I can remember my mother crying as she watched her beloved radio slowly submerging in that great pool of muck.

It seems funny now, but it was a calamity then. The depression had set in and there were few jobs to be had. My mother knew she’d never get enough money for another radio and it was the only pleasure she had.

We saved a few personal belongings from the mud-hole and arrived in Oklahoma with not much more than the clothes on our backs.

My aunt and uncle had a fair-sized farm and there was a lot of work for me to do to earn my keep. I was only seven but I felt a lot older. But I still believed in Santa Claus.

Two days before Christmas my mom took me aside and did her best to explain that there just wasn’t any Santa Claus for poor people.

My vision of a beautiful pair of leather cowboy boots for Christmas melted to nothing. I was too shocked to cry and besides my mom told me that, with my father gone, I was the man in the family.

I was too young to understand thoroughly what my mother meant by that, but I got a back-breaking example a few months later. Mom got a job picking cotton. I begged her to take me along.

In the fields all nature seems to be against you. The sun beats down like a blow-torch on your body. Insects attack your bare skin. The cotton grows low and you have to bend to, pick it. At the end of an hour your back muscles are screaming to relax, but they’re so full of cramps you can’t stand up straight. In the meantime, you find that as you pick the cotton the scraggy leaves and stems of the bush have laced your hands and finger tips with a thousand little cuts and every ball of cotton you pick is a movement of pain.

In early afternoon, just when you feel you can bear it no longer, things get worse. The sun is hotter, the insects are more numerous, and the cuts on your hands go deeper. By sundown you’re nothing but an exhausted lump of humanity.

Finish what you start

I wanted to quit a hundred times that day, but Mom wouldn’t let me.

When we finished we stood in a silent line of grim-faced people dragging our long burlap bags of cotton, waiting for the foreman to weigh them. Ten hours of excruciating labor and Mom got paid one dollar and seventeen cents. Mom said, “I just couldn’t let you quit, son. You might as well learn while you’re a young one that a man’s got to finish what he starts.” She cried and put her arms around me.

I went to bed early that night only a day older, but ten years wiser. I didn’t know how to spell it, but I knew better than any kid my age what the word responsibility stood for.

The next day Mom said she was taking me to school. I’d heard about school and teachers and didn’t like the idea at all, so I started to sulk.

Mom was patient for a few minutes. Then she said, “Would you rather pick cotton?”

I went to school.

The teacher told me I could get into the third grade if I learned the multiplication table in a week. I failed at that, so I went into second grade.

One morning in the school yard one of the boys, unknown to me, knelt down behind my legs. Another one walked up to me and pushed. I toppled over the kneeling kid and that started it. I got angry and jammed my knuckles into the nearest eye.

In their fists these kids held short sticks. And each end that protruded from the sides was sharpened to a point.

Ten minutes at their mercy and I was bloody from the holes they had punched in my skin. They left me on the ground. The teacher found me and brought me home.

Revenge

For days I planned my revenge. My chief object was to get the leader of the gang by himself. I finally cornered him late one afternoon. I was scared to death as I faced him, in the corner of the school yard. He was frightened, too. Then he ran by me toward the play-swings. As he ran ahead of me he grabbed a swing, took it a few feet with him, and then shoved it back at me.

After the doctor sewed it up I went back to school. None of the older guys bothered me any more.

When I was twelve I got mixed up with some kids who were making money stealing pigeons. There are a lot of pigeon fanciers in Oklahoma. We’d steal the birds in burlap bags and sell them.

I told Mom I was working after school, to explain the money. But one night she asked me questions about my “job.” I broke down and admitted everything. Mom looked at me as if I had cursed at her. I never felt so ashamed in my life.

The next morning, I sneaked into the back yard of the kid who kept all the stolen birds. I got to the roost and opened all the doors. They flew home.

A shootin’ feud

Then Mom took me to Alabama where she got a job in a grocery store. At the school there I made friends with a boy of fourteen. The other kids wouldn’t go near him and no one told me why. We got along fine until one day we were walking down the main street of the town. I heard a shot and the kid grabbed his shoulder and fell over. The street was suddenly a bedlam with policemen and excited people. They took my friend away in an ambulance.

A man with a sheriff’s badge said to me, “You’re a dang fool, kid, and danged lucky. Your buddy’s family is havin’ a feud with the Hokisons. They’re shootin’ each other up all the time. Go home!”

When I was fourteen Mom said she had saved enough to get to Long Beach, California where a relative was holding a job for her as a saleswoman.

On the West Coast things were booming. The depression was about over and in a month I had three jobs. I went to junior high, washed floors in two restaurants and sold newspapers. The beanery jobs gave me meals, the papers cash.

One afternoon while selling final editions, a Navy flier bought a paper. That wonderful green uniform he wore hit me like a beautiful bolt of lightning. In that instant my mind was made up. I wanted to be a Navy flier.

Day after day the desire got stronger and the ambition to pilot planes burned like a hot coal in my chest. I wrote the Navy Department in Washington and found that to get Navy wings you had to go through the Naval Academy. For three years I studied and saved for college. At the end of two years I had plenty of learning for my age, but no money and no chance for an appointment which was tough to get.

I enlisted in the Navy early in 1941 after I heard that sailors could take competitive examinations for the Academy. Too late I learned that I’d have to serve a year as an apprentice seaman before I could take the tests.

I spent that year as near to planes as possible, as a metalsmith, and wound up in Oklahoma, as an instructor.

When the war came the Navy put on a big drive for pilots. My commanding officer told me that I’d now have a chance to take my pilot’s exams. But, he added, there were only 200 openings and about 80,000 enlisted men were taking the tests.

No Santa Claus

I could hear my heart drop. Mom was right. There just wasn’t any Santa Claus. Nevertheless, I took the tests.

And the result was the first real break the world ever gave me. I made the 200.

Then the Navy sent me to the University of Georgia. The other guys in the program and I took four years of college in eighteen straight months of study.

After another six months of pilot training I joined Admiral Halsey’s Task Force 58. I flew Grumann fighter planes for two years.

When the war was over I was just another sailor wondering what I was going to do with the rest of my life. I was at loose ends so I went to Arizona where I punched cows.

One night my landlady kiddingly suggested that I might enjoy acting in a little theater group that had been organized in Phoenix.

Out of pure boredom I joined the group. And the instant I walked onto that dinky little stage I knew that I wanted to be an actor. I told the woman in charge I wanted to be a professional. Reluctantly, but kindly, the woman gave me the addresses of twenty-eight schools for drama, all located in New England.

I wrote letters to every one of them. A week later I got the replies, all discouraging, except one from Ogunquit, Maine. The letter was signed by Maude Hartwig, who later was a tremendous help to me. She suggested I come to Maine and study under the GI bill.

To Maine

I sold my jalopy and had just enough bus fare. I traveled four days and arrived in Maine without a dime. I talked a nice old lady into letting me have a closet-sized room in her boarding house. It was in the attic and had a bed and a table and one light. I’m not tall, but I could barely stand in the room.

At Ogunquit I did everything. Built sets, painted them, swept the floor, acted as ticket-taker and moved scenery. I did everything but act!

A month later Miss Hartwig said I could have a small part in a play called The Distaff Side.

Opening night was a fiasco. I forgot most of my lines, didn’t know up-stage from down-stage, got mixed up on entrances and exits, stumbled over scenery and in the third act became paralyzed.

After the show somebody said a talent scout from Columbia Pictures, a woman, had been out front and wanted to see me. I thought it was a joke. But she told me that if I could get to Hollywood she’d see that I got a screen test.

That same night I talked to a veteran drama instructor at the school.

He said, “Dewey, maybe you’ve got talent, maybe you haven’t, but right now you don’t know anything about acting.”

I called the woman from Columbia next morning and said I didn’t think I was prepared.

I stayed another year at the school and then went to New York.

In the big city I played a few minor roles on Broadway.

Then I operated an elevator in an apartment building to earn money for food.

Finally I heard about a drama group in Hollywood that was supposed to welcome new actors. I wrote them a letter. They replied, “Don’t come to Hollywood!”

So I came to Hollywood.

“Go home,” young man

In Hollywood I got a job as an usher at the CBS studios.

I worked mostly at night. During the day I tramped from one agent to another. Most of them wouldn’t even see me. Those who did told me to go back to Oklahoma.

Finally one agent got me a part in Knock On Any Door. I played a young hoodlum. In a wave of foolish over-confidence I quit my job at CBS. After two weeks work in the picture, I was unemployed again.

Then I got in the May Company department store as a package wrapper.

James Dunn had lost one of his important actors in his picture, The Golden Gloves Story. He had thumbed through Actors’ Guide, saw my picture and was reminded of my part in Knock.

The money I scraped together to get in Actors’ Guide was a good investment. Jimmy got to me at the May Company at 5 p.m.

At seven the next morning I was in Chicago. At eight I had a script. At nine I was before the cameras.

I hoarded the money from Golden Gloves. I lived for months on it and finally, after a lot of unsuccessful screen tests, Howard Hawks chose me for a big role in The Big Sky. When the picture was through, he signed me to an exclusive contract, with steady money every week.

Shortly after I completed Big Sky, I went to Sun Valley on a magazine story. I met Mardie Havelhurst, there. She was an Oregon State co-ed model.

A few months later we got married.

It didn’t work. In a year we weren’t happy any more. The reason? I don’t know and I don’t think Mardie did. But it was pointless to stay unhappy, whatever the cause. We got divorced.

After that I made six movies.

Then I got to play the young criminal in Desperate Hours.

Can you imagine acting with two Academy Award players? Frederic March and Humphrey Bogart!

Now I’m in The Proud And The Profane, with William Holden and Deborah Kerr.

Actors like Bogart and Holden and Miss Kerr are the best friends I have. And a man like director George Seaton makes you glad you decided to be an actor.

“Peggy and I”

Now all the other problems are working themselves out. We’ll spend a lot of time together, Peggy and I. Peggy took care of that beautifully. She simply cancelled all her professional appearances for the next three months to be with me on location shooting in Utah.

A lot of Hollywood producers have been wanting her since she got the “most promising actress” award in the Audience Award Polls last year.

But she hasn’t promised a thing to anyone except me and that was love, honor and obey.

You remember those beautiful cowboy boots I dreamed of and never got for Christmas when I was a kid? Well, I finally got them a few weeks ago. On the front of each one are my initials, D-M, in white leather. Peggy took one look at them. Now she calls me “Dewm-Dewm.”

We’re going to have a good life together. I’ll tell you something else. I’m too happy to talk about myself any more.

You see that ship out there?

It’s a freighter, you can tell by the dips in its silhouette, fore and aft. Ten-thousand tons, about. It’s packed with crates, bags, cars and people. A few passengers, but mostly crew. But, traveler or sailor, every one of those people has a head full of dreams. Some little, some big. We’re all that way, I guess.

I guess I’m sounding like a corny poet. But it’s true. Every one of those people out there on that horizon are strangers to me, but the way I’m feeling I find myself wishing hard for them, hoping they all find what they’re searching for.

Nothing’s too tough for a guy with hope.

RITA MORENO: I Fled The New York Slums

Three years ago I went back to visit the little room in the Bronx flat in the New York slums in which we had lived, my mother, my brother and I—and I was horrified. It was so small, so drab and dark, so crowded with all the possessions of a whole family living there in one room, the same way it had been when I lived there with my family.

I told the people in the room that once it had been my home and they looked back at me with dull eyes, taking in my new clothes without envy, but seeming to ask a question: How had I ever escaped?

How had I?

It was a long, hard struggle.

There are about a half million Puerto Ricans living in New York, many in complete hopelessness, and we were among those who suffered badly. When my mother brought me—a four year old—from the town of Humacao in Puerto Rico to the United States, she supported us by her work as a seamstress. She made shirts then. I don’t know how much she was paid but it was low enough so that she used to complain bitterly about getting so little for them.

I was far from a help; to tell the truth I had a miserable time at the start. I was sickly, I couldn’t speak a word of English, and I felt like a stranger lost in a huge, friendless city.

I remember that on my first day in New York I came down with chicken pox and was taken away from my mother in an ambulance; frightened to death, convinced the devil or worse had me. (You don’t go to the hospital with chicken pox ordinarily, but this apparently was Board of Health policy with cases in areas as congested as ours.)

They put me in a large ward and there I lay, jabbering away in Spanish and understood by no one, as far as I knew, until I noticed a little boy of my age across the way. I could tell he was a Latin and that he talked Spanish—and I was right. But it did me no good. He didn’t like girls and he wouldn’t speak to me.

I learned my first two English phrases in that ward. I learned to yell at the boy: “Hey, you!” And I learned what he meant when he yelled back: “Shut up!”

I shut up. Lying there on my little hospital cot I began dreaming my way into a better life. I mean that I sensed when they washed me and treated me, that I was getting tender care, with sometimes love behind it; and that there was a goodness involved, a large goodness, in the hospital, in the city in which it stood, and in the country around it. And I felt that one could become part of it all if one wished.

The wish was important

I wished. Hard. And, don’t worry, I am not going to make this into a fairy story. Wishing didn’t get it all for me. What I look like, what talent I have, what luck came my way—all this has helped. But at that time I had no looks—I was skinny, just a stick with black beans for eyes; I had not so much talent as urge, and my luck was always lousy.

So the wish was important. It’s always important. The wish made me go to my mother and beg to be taught something—to be taught something even before I started school the next year when I would be five. “I want to learn,” I cried.

“Learn what?” asked my mother, spreading her hands wide apart. “What could a little thing like you want to learn?”

I thought of what I liked and the answer was simple. There was something I liked more than anything else. To dance. And dancing was something my mother must have understood too, I guess. Because if I had said something else, she might have done nothing. But I wanted to dance, and she wanted me to dance. So she worked the harder and sent me to the best teacher we knew, Paco Cansino.

It is funny, but just to be learning something is in itself a thing of hope. I walked around my city as before. It was the same city. But now different to me because I was becoming something—a dancer. Did the people know, I wondered, as they passed me? And that’s what hope is: same city, different girl; same poverty, but you can’t see it for the dreams you’re wrapped in.

I learned to use my dreams for excitement in those days. I would go into the five-and-ten, walk and look around, and tell myself I could have anything I wanted. Sometimes I would overdo it; suddenly I would know I couldn’t have anything, and I would burst into tears and run out of the store. What I am trying to say is that I didn’t completely escape the misery of poverty. But I wasn’t beaten by it.

When I was five years old there were two important events in my life. I danced publicly for the first time in a Greenwich Village cafe (with Paco), and my mother entered me in kindergarten at P.S. 132. The dance was a success. People laughed and applauded. The school episode didn’t start off so well. I was frightened and refused to stay in class without my mother when she wanted to leave.

“All right,” she said to me in Spanish. “You wait here while I go and get some gum. Then I’ll be right back.”

I waited, and after a while knew that something was wrong, that she wasn’t returning. And I was ready to cry, I guess, when something extraordinary happened. The teacher went to the piano, began playing, and we children danced.

I forgot all about my mother and the gum, and joined the dancing. So this was school in New York! I had never imagined anything so wonderful.

That night I insisted on sleeping with my clothes on so as not to be late for class. My mother scolded. My aunt and cousins also raised a fuss. But they made no impression on me. They weren’t even in my world.

I mean I was still in the midst of awful drabness. But if I have told this right, you will see how I was also far, far, out of it!

“Look at that little one!” my aunt used to say. “Where is she? Not here!”

And I wasn’t.

Danced for health

I don’t want to say things as if they are facts when I am not sure that they are, so I will just give some opinions here. I had anemia when I was a child and I think I was cured by dancing. I think that dancing is more than just exercise, I think it restores health and brings beauty. I think that if a girl is going to be shapely she’ll be more shapely if she dances a lot. And if a girl has a tendency not to be shapely I think she might still get a nice form by dancing herself into one.

For all those years I’ve never stopped dancing.

That time when I danced in Greenwich Village ‘at the age of five was just a lark to please my teacher, Paco. My debut as.a “professional” came at the age of nine. The daughter of Jewish neighbors whom I knew was going to sing at a Bar Mizvah, celebrating the thirteenth birthday of her younger brother.

“You come too and dance for them,” said the girl. “They would love it.”

My mother made me a fruit salad of a hat and I did an impression of Carmen Miranda. They did love it. And they made me join them in a Hebrew dance they did, the Hora, with everyone joining hands and revolving in a circle. And afterwards they paid me five dollars—and I was no longer an amateur! All the way home I floated. And there I sat and looked around at our meager quarters and thought to myself, “I’m on the way.”

I didn’t so much mean that I was on my way some place as that I was on my way out of there. At any time in my youth I could have accepted what I was, where I was, and let myself sink there. But I didn’t. Life put its finger on me many times and pushed me under but I slipped aside and bobbed up again. Getting on the stage or into the movies were constant thoughts in my mind, but never possessed me as much as the simple desire to improve myself so I could live as I knew people should—humanly and decently. It meant work—and I worked.

The big chance

After the Bar Mizvah I began dancing in a little theatre in Macy’s department store, doing routines after school and on weekends. After three years Paco and I figured out that I had performed 770 times. But I did more work than that. My Macy’s dancing got me into early television—experimental TV for Dumont Network and others. I never got paid either; they used to tell me that it was my big chance because only producers could afford television sets those days and I was sure to be seen by someone important.

Maybe they fooled me but I don’t think I worried about it much then. The big thing was that I was getting noticed. An agent came to see me and to handle my engagements. Places where I had danced sent for me to come back. I was cast in a Broadway play Skydrift (which ran a week). One day my agent took me to see Elizabeth Taylor in National Velvet and afterwards made a recording of my translation into Spanish of four of Elizabeth’s lines from the picture. The next thing I know I had been taken to see Carlos Montelban (brother of Ricardo) who was in charge of dubbing American pictures into Spanish for MGM productions. “How would you like to be Elizabeth Taylor’s voice whenever her pictures play in Spanish-speaking countries?” he asked. You know what my reply was. And from then on Elizabeth Taylor, or maybe Margaret O’Brien or Peggy Ann Garner would be the actresses Spanish fans would see, but it was my voice they would hear speaking for these stars. And finally I began making records of radio commercials in Spanish.

I can remember thinking to myself then: “I am thirteen years old and I am a somebody.” I don’t think that people should go around being proud, but it isn’t wrong to be proud enough—to be proud to the point of being able to feel, “I am this.” No one should feel that she is nothing.

Mr. Law steps in

It wasn’t always success with me. When I was fifteen I began having a bad time. There didn’t seem to be much work and when I did get it, Idid badly. I got a week’s work in a big night club in Manhattan, Leon and Eddie’s. and they just didn’t like my dancing. I did Classic Flamenco. They wanted modern. This made me just want to learn that much more.

One weekend I got a job in a small Bronx night club, being offered $20 for Saturday and Sunday. I was just getting ready to go on and do my dance for the second show Saturday night when the owner of the place suddenly grabbed me, sat me at a table, and threw a fur coat around me. “Act like a patron!” he hissed. And then I saw what was wrong. A police officer had entered the place and In New York you cannot work in night clubs if you are a minor, and I was only sixteen. I put on my “twenty-one-year-old look” but I didn’t fool Mr. Law. He sent me home.

Finally, I was so desperate that I took a step I hated—I started to go to secretarial school. I paid $30 for a six week course, but quit in three weeks to take another dancing job when it was offered to me. I had learned to type fairly well and even had a smattering of shorthand, but I already knew that it was dancing which was going to make the big difference in my life.

“We’re free”

Actually I didn’t get to leave that one room where I had spent most of my life until I was eighteen years old. One afternoon at that time I came home and showed my mother some papers I had.

“What is it?” she asked in some alarm.

I guess I sat down and cried. “It is our freedom! We can get out of here.” I hurried to add, before she got the idea that she was being dispossessed, “A movie contract, Mom! We’re going to California!”

How had it happened? Simply. Without drama. I had been in another play, Signor Chicago, with Guy Kibbee. It wasn’t a big hit and we all knew it wasn’t going to run long. But it turned out to be a big success for me. Someone saw me; someone came to talk to me for two hours about the sort of roles I might be able to fill in Hollywood, and that someone signed me. His name was Louis B. Mayer and it was at the studio he headed then, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, that I started.

Now, six years and fourteen pictures later, I am at 20th Century-Fox Studios, getting my biggest chance, with Deborah Kerr and Yul Brynner, in the movie version of the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical play, The King And I.

I don’t know whether I will become a big star. Believe me, this is not important. I only have to remember how harsh and mean life can be, and I’m willing to settle for much less than stardom. For just ordinary happiness, for instance.

What I want most to say is that I have escaped. That’s what I would have liked to tell those people who live in the same room we had. That alone is worth it all.

THE END

—AS TOLD TO LOU LARKIN

Dewey can currently be seen in Paramount’s The Proud And The Profane.

Rita can currently be seen in the 20th Century-Fox film The King And I.

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1956