There Was A Boy—James Dean

PART III

“Death,” Jimmy Dean said, “‘is the only thing I respect. It’s the only thing that has any dignity.” Strange words for a brilliantly successful young boy to utter, but the moods that evoked the words were stranger still. Before you read this third and final installment of Jimmy’s life story, we suggest you read the editorial piece on this same page, finish the story, and then reach your own conclusions. Did Jimmy Dean have a premonition of death? Or was he obsessed with thoughts of dying?

When I left New York to return to Hollywood late in 1953, James Dean presented me with a collection of short stories by Andre Maurois. The inscription read, “To Bill: While in the aura of metaphysical whoo-haaas, ebb away your displeasures on this. May flights of harpies escort your wingéd trip of vengeance.” Since leaving Hollywood almost two years previously, we had both come to look westward with a vengeful eye. My turn to revisit the city of make-believe came first, and in a manner of speaking Jimmy envied me for it. Several months later, when his turn finally did come, Jimmy collected for himself a whole armada of screaming harpies to help protect him from the individuality-debasing influences of the publicity capital of the world.

Jimmy felt deeply that he, like many other enterprising young hopefuls, had suffered too many indignities while running the gamut of the accepted methods of breaking into movies. Too many doors had been slammed in his face. Too many casting directors and agents had treated him with disinterest and disrespect. Too many unpleasant people in positions of influence and authority had demanded of him too much flattering attention. Two years before he had not been wise enough, aware enough, confident enough, to know better than to play along with their degrading games. He had been a hopeful, naive boy who believed in those foolish prescribed methods for getting ahead in movieland. But he had grown a good deal in New York, and he returned to Hollywood much taller and much stronger.

He arrived in Hollywood in an enviable position. He was there to take a starring role in Elia Kazan’s newest and most promising masterpiece, “East of Eden.” His only desire was to make the picture and return to New York and the Broadway stage. He didn’t need Hollywood and, perhaps, Hollywood didn’t need him. But he had found out one very important thing about himself which gave him the advantage: He was a competent and talented actor and had, as far as Hollywood was concerned, a sale-able commodity. If they were willing to pay for his best, he was willing to sell it.

But talent was all he intended to sell them. He had established a rigid set of standards and values, most of them adhering passionately to individual integrity and basic honesty. He was determined to have no truck with the dishonest nonsense so prevalent in glamorville. There would be no great publicity campaign for James Dean, no star-studded crown to wear as a false laurel wreath, no blind acceptance of shallow standards, no falling into the trap of believing that stardom brought with it fulfillment and completion. His aim had been for a long time higher than Hollywood and he didn’t mean to lose sight of his ultimate goal: to be a fine and accomplished artist. He knew he had a long way to go and a lot to learn before his day of arrival.

The level of Jimmy’s standards had been set so high that the constant application of them would have been nearly impossible for anyone. He must have known he would falter and stumble, make mistakes, but he would pick himself up again and learn from those mistakes. His ideals were right and worth fighting for, and he was dedicated to that proposition. And along the way, he would not permit Hollywood to bury him in the permanent grave of stagnation as it had done to so many before him. Hollywood would have to accept him on his terms, or not accept him at all. About this he was adamant.

Early on the morning after he arrived, he came to my apartment and announced that he was taking me with him to the desert where he intended to get a suntan, as per Kazan’s instructions. Within an hour we were on the road to my favorite desert retreat, Borrego Springs, about one hundred miles beyond Palm Springs.

Understandably, Jimmy was excited about doing his first movie, especially since it was to be directed by Kazan, for whom he had a great deal of admiration. He told me of the plans for the film and chuckled at one point over a comment Kazan had made. It was the director’s feeling that the ole Jimmy was to play could very well put him in the running for an Oscar in the next year’s Academy Awards race.

In our younger, more critical days we had often joked about the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences and their yearly Oscar presentations as being chauvinistic, heavily influenced by studio prejudices and politics, too often ruled by saccharine sentimentality, and generally lacking the objectivity so necessary in criticizing art. It was natural, therefore, for me to ask him what his reaction would be to winning an Oscar. He admitted that he was not really concerned with the matter, but that he felt he would only win the award as a result of giving a performance that was too obviously good to be ignored. In that instance, he would accept it exactly for what it was—an honest prize won in a fair game.

But he felt strongly that they would dislike him so intensely in Hollywood that they would never vote him an Oscar, unless public opinion, for some reason or other, were to force them. Noting the Academy’s decision to grant him an award next March due to the strong public re-action to their neglect of him in last year’s race, I can only marvel, though sadly, at Jimmy’s astute perception.

Immediately upon our return from the desert we went to Famous Artists, the agency that was to handle Jimmy’s affairs on the West Coast. Bearded and shabbily dressed, we were led into Dick Clayton’s office, where Jimmy met for the first time the young agent who was to become his friend and adviser. Jimmy had had over a week to mull and brood about the Hollywood situation, so Dick, being his first contact with the town that was a potential threat to him, got the full brunt of his defensive attitude. As best he could, Dick, a charming guy with an easy manner for handling temperaments, tried to show Jimmy that he was on his side, but Jimmy did nothing to ease the strain. After about an hour of discussing the plans and procedures for starting the film, we left Dick, who must have felt he surely had a problem on his hands. Outside Jimmy remarked, “Nice guy. Guess I’ve got him worried.” It was his intention not to give Dick Clayton trouble, but slowly to invest in him his trust and confidence. He was not going to make it easy for anyone. This time they would all have to earn his confidence.

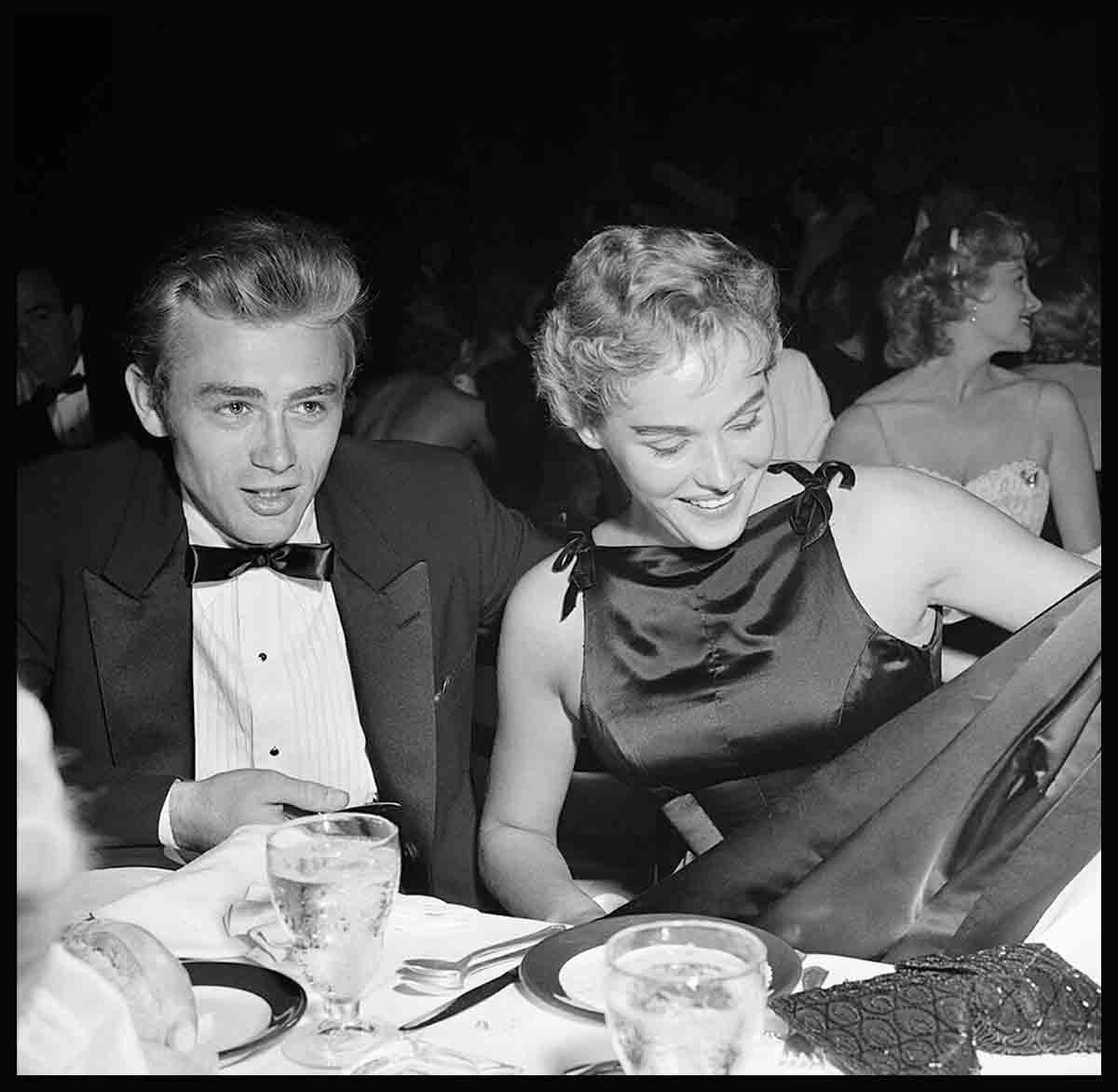

For a while it was as though Hollywood was a new place to Jimmy. There were few, if any, old friends to look up, and no old ties to re-establish. He floundered a bit at first, meeting new people and adjusting to a new life. With the help of Dick Clayton he found a bright red MG, a great improvement over the 1937 car he had owned several years before, and gradually began finding his way around movie-town again. He started dating some of the young starlets he met. Karen Sharpe, whom he had known before, and Terry Moore went out with him frequently.

Jimmy spread out and enjoyed himself for a few weeks, as if he were ridding himself in as short a time as possible of a natural desire to sop up some of the old, and once unattainable, superficial glitter of Hollywood. By the time filming started on “Eden,” he had had it and seemed ready to settle down to the serious task of creating a character.

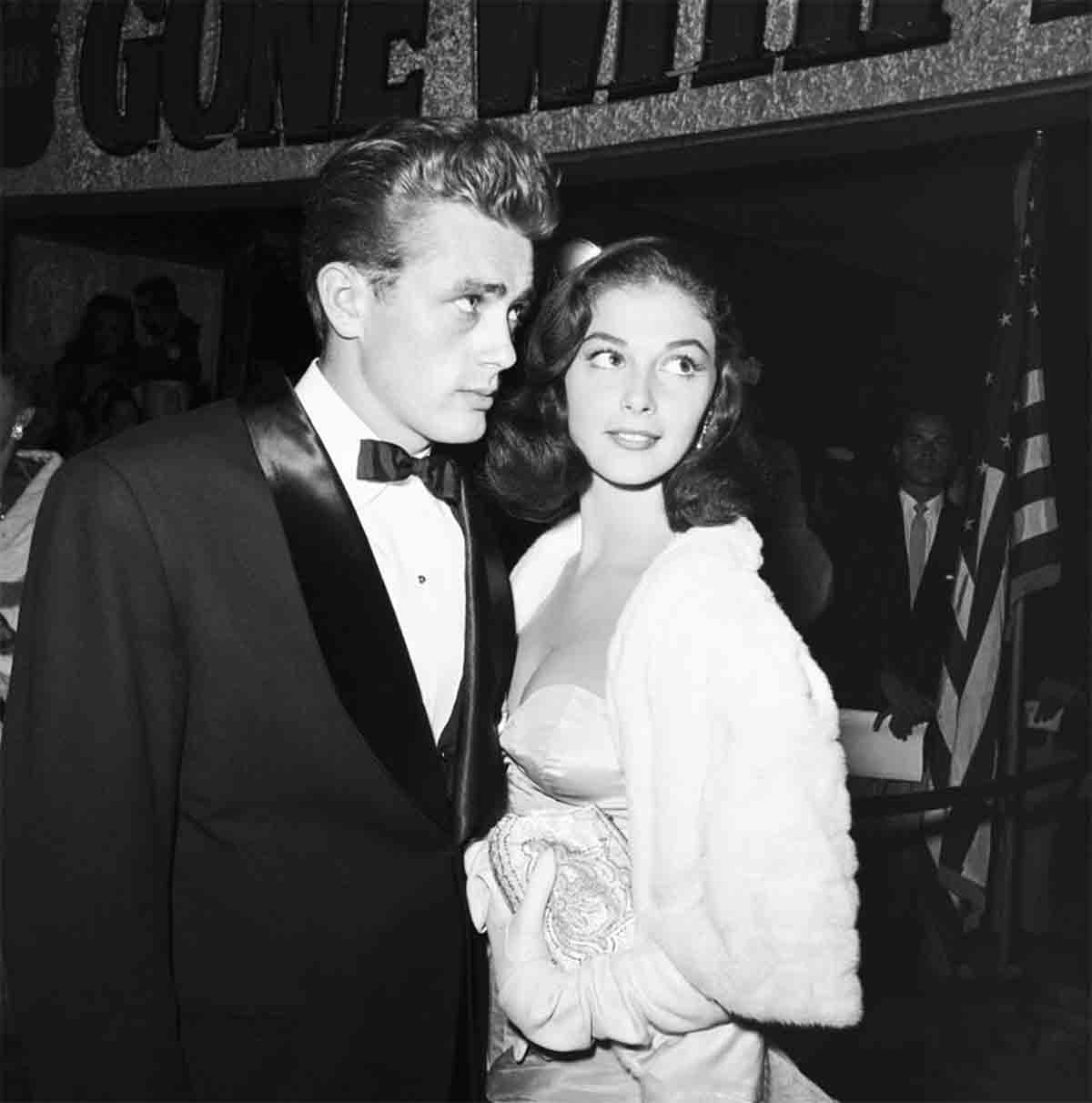

It was during the filming of “Eden” that Jimmy met Pier Angeli. The strong fascination they had for one another developed into something fine and beautiful. Jimmy sought her out and tried to spend much of his time with her. When I asked him about her, he replied that she was a sensitive girl with a wonderful mind, someone who understood him and with whom he could be at ease, but, he insisted, it did not go beyond that. “Methinks thou dost protest too much” kept running through my mind as he denied the press’s implications that there was something more serious than just friendship behind their relationship.

There was something in his manner of underplaying it that indicated a deeper attachment than he would have cared to have had known. About most matters he could be flip, but about matters of consequence he was often shy and guarded. It is a known fact that Pier’s mother openly objected to the relationship and made things very difficult for them. They say that when Pier married Vic Damone, Jimmy stood across from the church and cried. I do not know this to be true, but if he loved her, it is something he might have done. When Jimmy loved, he loved completely, and when he lost the object of his love, he suffered completely.

As soon as “Eden” was completed, word started to seep out that Warner Brothers had a great new star in James Dean. The studio screenings and audience previews were drawing the best reactions, and it was becoming a matter of great excitement around town. Hollywood was abuzz with the name of James Dean. Jimmy’s anxieties mounted as the release date on the picture drew near. Consequently, he snatched at a chance to return to New York to do a live TV broadcast and to study. He seemed to feel an ominous foreboding of the sensational fame that was to come out of his first picture, and was hoping to maintain a degree of objective sensibility and rationality about the situation by getting away from Hollywood, a place where one can too easily begin to believe what one hears about oneself.

In New York Jimmy touched once again the fibres of those things that were really important to him. He studied acting, singing, dancing, drums, doing occasional roles on TV. Due to contract stipulations, he was not free to leave Hollywood for Broadway, as he had wished, but was being held for more picture work. So, while in New York, he absorbed enough of the creative atmosphere from which he, as an artist, had emerged to last him through the trying days ahead in Hollywood. He was determined, at least, to return to New York after each picture to reaffirm himself. It was with reluctance again that he left the big city to return for the preparations of his next film, “Rebel Without a Cause.”

Jimmy had long been a motorcycle enthusiast, having owned several different bikes in Indiana as a boy. He had a new motorcycle in Hollywood and was proud of it, since it was by far the finest he had ever owned. He was a good cyclist and took pride in demonstrating the fact. Often he could be seen roaring down Sunset Strip in the direction of Googi’s, a favorite restaurant with the young film actors.

Kazan and Warner Brothers had warned him to stay off the bike while making a picture. The studio’s investment was too great to risk an accident which might delay filming for weeks or months at a tremendous cost. But they had no jurisdiction over him when he was not filming, so he mounted his motorcycle and breezed through town, enjoying the sensation of liberation that every cyclist must know and appreciate.

Ella Logan, a close friend of Kazan’s who often visited him at work, developed a fear of Jimmy’s craze for motorcycling soon after they met on the set of “Eden.” Ella is not only a remarkable performer and fascinating personality, but also a woman intensely interested in creative young people. She was immediately drawn to Jimmy and admired in him all the dynamic force and sensitive beauty that so many others had misinterpreted as arrogance and an anti-social attitude. It was at one of the impromptu parties at her home in Brentwood, where she often invited young people like Jimmy, Sammy Davis, Jr., Marlon Brando, that she asked Brando to speak to Jimmy about the motorcycle. As he was leaving, Brando advised Jimmy to give up the motorcycle, pointing out that an actor with half a face was no actor at all. Jimmy seemed to shrug the incident off. Ella feared the battle was lost, but a short time later Jimmy informed her that he had disposed of the bike because it was too dangerous. For a time, Ella and most of his close friends were relieved.

Then, just prior to the making of “Rebel,” he bought his first real sports car, a German-built Porsche. He took it to Palm Springs one weekend and entered the road races, winning first place in the amateur class the first day, and third place in the professional class the second day. It was the first time he had ever raced a car and he brought his trophies home to Hollywood and displayed them with enthusiasm. It was apparent that sports cars were going to replace motorcycles in his life.

It was at this point that most of Jimmy’s friends realized that to make him give up sports cars would be as futile as making him give up motorcycles had been. There would soon be something else, equally dangerous, he would find to take the place of the thrill he got from defying death in a racing car.

For a long time Jimmy had been addicted to the ecstatic pleasure he derived from the frenzy of speed and the emotional excitement of taunting death. Although he had a normal degree of the fear of dying, he intellectualized that in death there was great dignity and nobility. He reasoned that death was ultimate and undeniable Truth. It was, he claimed, the only thing he completely respected. And he, like the bullfighter he wished some day to be, seemed to have a morbid fascination for the things he feared the most. There was nothing any of his friends could ever have done to change his attitude.

During the filming of “Rebel,” Jimmy slipped into a different way of life. Perhaps it was the essence of the role he was to play, or the mental unrest of the more complex characters of the movie’s story that made him want to re-experience the sensations of being lost, unwanted, and different from the norm. Or, perhaps, it was not so much a matter of study and re-search, but more a definite and strong feeling he had that he, too, belonged partly to that portion of humanity that is lost, alone, and confused. In either case, as he once put it to Ella Logan, “I like you, Ella. You’re good. But, you know, I like bad people, too. I guess that’s because I’m so damn curious to know what makes them bad.”

By “bad” I don’t think he meant precisely “evil.” People with odd viewpoints and strange modes of existence always intrigued him. It was probably more in the sense of “different” or “unusual” that he used the word “bad,” but at some point during his early Quaker background, he must have learned to associate “bad” with those actions not conforming to the normal and accepted patterns of conduct.

He met and befriended Maila Nurmi, famous for her Vampira role on TV. Maila is a compassionate girl who understood him and tried to help him where she could. Their relationship, contrary to unfortunate rumor, was strictly one of friendship and intellectual rapport. With Maila and several of their mutual friends Jimmy started what has been dubbed “the night watch.” In the cool damp hours of early morning, life in Hollywood, as in any other place, assumes a weird but enticing perspective. The world becomes a place where lonely and frightened souls can be free and secure, having shut out the terrifying life of daytime. It is a place where misery is understood, but forgotten, where sorrow is inherent, but ignored. It is an easier place to live, if you are afraid, or if you do not belong. From this place, then, was bred the spirit of the character Jimmy was creating in “Rebel Without a Cause.”

By the time the filming of “Rebel” was finished, Jimmy was already steeped in preparations for George Stevens’ next film, “Giant.” He had come to know Stevens and the other people in the office as a result of hanging around during his off-hours at Warners. One day, after reading the “Giant” screenplay which Stevens had given him, Jimmy confided to Stevens that he would like to play the part of Jett Rink. He was surprised to learn that he had actually been considered for the role. As Stevens tells it, “Jimmy seemed amazed that we wanted him for the part and didn’t seem to expect it.” When Stevens asked if he felt he could handle the age change from eighteen to fifty, Jimmy affirmed that he was sure he could do it well. He was assigned to do the role and began to learn how to be a Texan.

As he was with most people, Jimmy was inconsistent in his attitude toward Elizabeth Taylor when they first met shortly before the start of “Giant.” The day they were introduced Jimmy was charming, even to the point of taking Liz for a ride in his new Porsche. His whole approach was contrary to everything she had been braced to expect from him. She went away thinking people were crazy for calling him an anti-social odd-ball. The next time she saw him she approached him in her usual friendly manner, expecting from him the same warm reaction she got the first day. Instead, she was surprised when Jimmy glared at her over the upper rim of his glasses, muttered something to himself, and strode off as though he hadn’t seen her. As would anyone, she took this as a personal affront. It was not until they were in Texas on location that she succeeded in finding out the truth about the mystery of Jimmy’s behavior.

At dinner in a Texas country club one night, Liz found herself seated at the table alone with Jimmy. After a long, deadly, unbearable pause, she turned to him and pointedly stated, “You don’t like me, do you?” Jimmy began to chuckle. “I like that,” he replied. The simple directness of her challenge had the kind of honesty he appreciated. For the rest of the evening they talked in a free and easy way and, for the first time since they had met, Jimmy let Liz pass through the tightly guarded protective shell he often put up around himself. After that, Liz stopped taking offense at what he did and stopped feeling hurt when he was moody around her. She had discovered that his moods and actions were simply a part of his complex nature and were not meant to be taken personally by those who were unfortunate enough to be around at the time.

Sanford Roth, the still photographer on “Giant,” is an internationally respected artist, having done photographic essays on many of the world’s most famous artists and intellects. As he slipped around the set getting shots of the cast, he noticed that Jimmy kept on him the same suspicious, wary eye he kept on Warner Brothers publicity people. Studying Jimmy at close range, Sandy began to see in him the same qualities he had come to know in so many of the other artists with whom he had worked.

Finally Sandy approached Jimmy and informed him that he would like to be his friend. In plain terms Sandy explained that he did not need Jimmy for anything, that he was, in his own right, an artist of some repute, and a man of sufficient means. He made it very clear that he wanted to be a friend solely because he admired Jimmy’s talent and respected his way of thinking. Once again the directness of the approach so appealed to Jimmy that he responded almost immediately. It was not long before both Sandy and his wife came to occupy a prominent position in Jimmy’s life.

When Jimmy discovered in the Roths a source of intellectual stimulation and growth, he developed a great spiritual need for them; when he discovered in them a source of love and comradeship as well, he developed a great psychological need for them. The Roths are people in their middle years, but their lives are so filled with work and growth that they have and probably will always have a perpetual youth about them. They understood Jimmy’s insatiable curiosity and desire for knowledge and they offered him what they had. He began spending much time with them, dropping in at their home, raiding the refrigerator, playing with Luis, their Siamese cat, and discussing things, all sorts of things, with Sandy and Beulah, who have an abundance of enthusiasm for everything worthwhile. The pattern of the “second mothers” was repeating itself, and little by little he came to regard them as a family.

The work on “Giant” was coming to a close. Jimmy was once again thinking of the future. There was another road race at Salinas. There was time to make a trip back to New York before starting on “Somebody Up There Likes Me” at Metro. There were thoughts on his mind of a long-delayed voyage to Europe, of another Broadway play, of all the studying he wanted to do before he could become a director or a writer, of the possibilities of a production company of his own. So many things, and so little time. It seemed to be the story of his life.

A few weeks before the finish of “Giant” Liz Taylor went out and bought Jimmy a tiny Siamese kitten. She had noticed how exceptionally well he got on with the Roths’ unusual Siamese cat, Luis, and how well Luis got on with Jimmy, and she wanted to do something nice for Jimmy. She presented it to him in her dressing room on the set and watched as Jimmy, speechless with gratitude, fondled the little creature.

In the days that followed Jimmy grew to love little Marcus, as he dubbed him. Here for the first time in many years he had a being he could love and be loved by, with less of a risk of losing that love. He was attentive to the point of driving home from the studio at lunch to feed Marcus and be with him for a while. He even began getting in at more reasonable hours to be able to spend more time with the pet he loved so much. He rigged a long cord with a knot at the end which hung from the two-story ceiling of his rustic living room, and sat by the hour chuckling at his little friend as the kitten would smack the knot with his terrible little paw, stalk it like a lion stalking its prey, cling to it and swing like a miniature feline Tarzan, and be

own in a tumble to the floor, where he would shake his dazed little head and prepare for another attack. For all the amusement and affection Marcus gave Jimmy, Jimmy, in turn, gave Marcus his love and attention.

It was a shock to the Roths when Jimmy announced, a few days after the finish of “Giant,” that he had given Marcus away. When they asked him why, he replied that he was too concerned for his friend and realized that he led such a strange and unpredictable life that some night he might just never come home again. “Then,” he asked, “what would happen to Marcus?” Less than a week after he gave Marcus away, Jimmy died near Paso Robles, California, never to return home again.

Jimmy is gone now, and I miss him. All of his friends miss him. Millions of his admirers and fans, who came to know him through motion pictures, miss him. But there is no need for me to eulogize him, to sing out praises to him. There is no need to extol his virtues, and no need to hide his errors. He was here with us for a while, but now he is gone. Let us be content to have known him, if even for so short a time. Let his art be his memorial. Let his immortality be the tribute to his life. Let the silent love of those who knew him be a lasting symbol of the beauty of his soul.

In his “Divine Comedy” the great classic poet Dante said, “Sorrow remarries us to God.” I am content to know that Jimmy is at peace in the consummation of a marriage that, it seems to me, took place the day he was born.

THE END

—BY WILLIAM BAST

YOU’LL SEE: James Dean in “Giant,” a George Stevens Production for Warner Brothers.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1956