Poignant Truth About Shirley MacLaine’s Private Life

Shirley clowned it up that night like never before. She perched herself on the piano and sang. She jumped off the piano and danced. She joked around with everybody and she helped pour the champagne and she drank some of the champagne and she had herself a wonderful, beautiful ball.

And why not? This was the most wonderful, beautiful night of her life, wasn’t it?

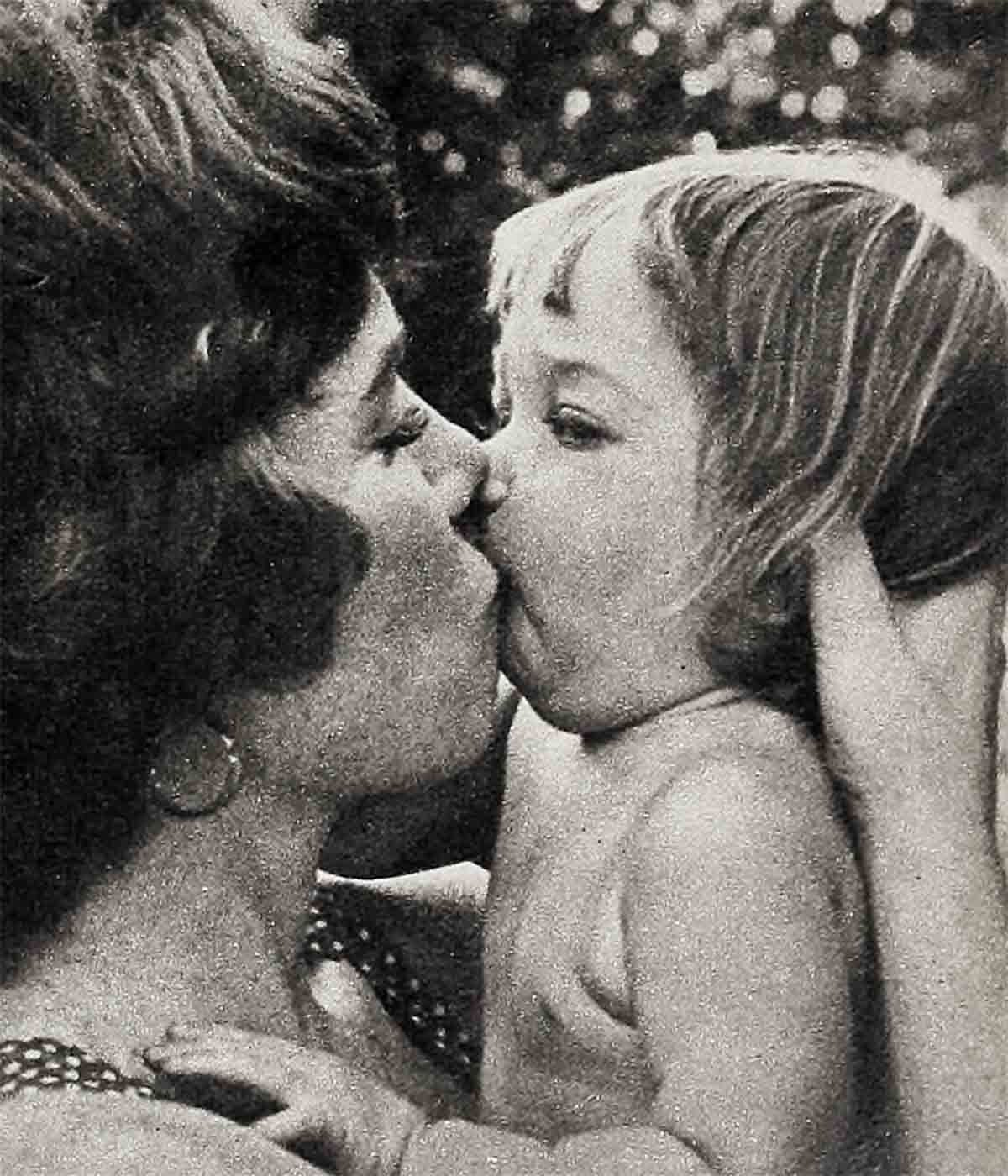

A few hours earlier, Some Came Running had been premiéred and the pixie-faced freckle-covered girl from Arlington, Virginia, was suddenly the toast of all Hollywood, a great big new star. And in just a few hours from now Steve Parker, her husband, in Japan for practically a year, would board a plane in Tokyo and in less than a day he would be back home—for a few months, at least, in her arms again, with her again and their daughter, Stephanie.

Oh yes, this was Shirley’s night, a night to be remembered and enjoyed, a night to laugh and to forget that there was anything but laughter in this life.

But then, a few minutes after one o’clock—just when the party was at its height—the telephone rang.

“Do you want to take the call in that bed room?” a maid asked, pointing. “It’s your husband.”

“Steve??” Shirley called out, amazed. brought her hand up to her face. “Oh gosh,” she said, “maybe he’s arrived already. Maybe it’s a surprise. Maybe he’s at the air port right this minute!”

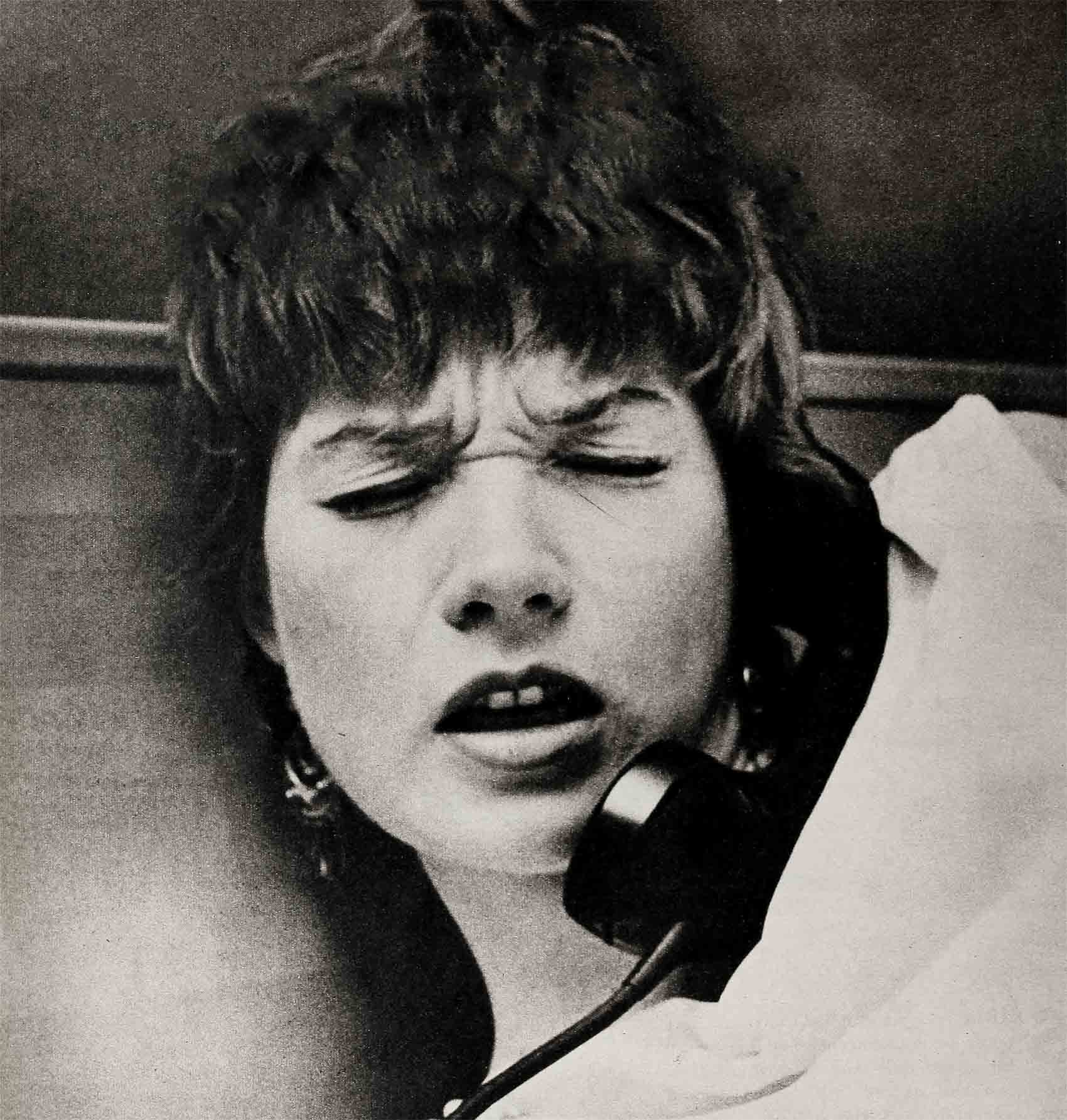

She stood frozen to the spot for a moment. And then, crossing her fingers, she raced across the room and into the bedroom and picked up the phone.

“Steve darling?” she asked, catching her breath. “Where are you?”

A flash of static cut off his first words.

“Steve?” Shirley asked again.

She heard his voice now.

It was barely audible.

“. . . Tokyo . . .” she heard him say. “I’m still here. . . .”

“Are you getting ready to leave?” Shirley asked.

For the next half minute there was a garbling of words.

And then, for a moment, his voice came over clear again.

“I’m sorry, honey,” she heard him start to say, “but I’ve got to stay here another three—”

Suddenly, the static hit the receiver again.

The smile vanished from Shirley’s face, the laughter from her voice.

“Three what?”

There was no answer this time.

“Steve—” Shirley said, louder this time, “how long will it be before you come back to me? Please tell me. How long do I have to wait now, this time? Three days? Three months? Three years? How long, Steve, how long?”

She held the receiver tight against her ear, despite the terrible static.

When the line did clear, finally, it was not Steve who spoke but the operator, who politely explained that there was bad interference on all lines to the Orient at that moment and would she please hang up and wait a few minutes till the interference was gone. Shirley put down the receiver.

She walked across the room and sat down. As she did, there was a knock on the door.

“Shirl,” a voice—her host’s—hollered, “is everything all right in there?”

“Yes,” she managed to say.

“Tell Steve hello,” the voice hollered.

“Yes,” Shirley said.

“And come on back out when you’re through,” the voice hollered. “We miss you.”

“All right,” Shirley said.

She closed her eyes.

She kept them closed, until the moment a flood of trapped tears caused them to open.

“Oh God,” Shirley called out suddenly.

She wiped away the tears with the back of her hand, hard, angrily, and she stood up and opened the window.

Things that were meant to be

It had begun to rain sometime during those last few minutes, Shirley realized now, a thick and heavy rain. And below her, way down in the ravine below the window, she could hear the tiny gurgle of a new-formed stream racing from somewhere to somewhere.

She listened for a while.

Then she looked down.

It was black outside, tar-black and wet, and she could see nothing.

Then she called out to the black night, “Oh God, why does it have to be like this, all the time, all my life? I thank You for what I have, for my success. But why must I sacrifice so much to get the things I’ve gotten? . . Now, tonight . . . Last year . . . The year before . . . Even when I was a child!”

Somehow, staring like that, down into the vast nothingness, the scene around her seemed to change and the time seemed to be slipping away from her and she could see a stream, clear and sparkling with sun-dots and filled with darting minnows and with green, fresh-fallen leaves floating lazily on its surface.

Even when I was a child—the words echoed through her brain again. Why?

And then a voice from the past came to her.

Now Shirley, you get away from this stream and come home and get out of those overalls and get dressed,she remembered her mother saying. You’re a big girl of seven now and you’ve got to understand that it’s all well and good for you to want to be a tomboy and play down by the stream all afternoon . . . but there are afternoons, you know, when I’ve got to take you to your dancing classes. How many times do I have to tell you, Shirley, that those feet of yours are weak and these dancing classes are good for you . . . Now you just try to realize that there are things in life you’ve got to do, things that were meant to be.

That was the beginning, Shirley realized now—getting used to things that were meant to be—right there, right at the beginning, when poor health of a sort had caused her to give up the part of her childhood she most relished, those hundreds of hours she’d liked to have spent with her brother Warren and his pals, playing pirate down by the stream, playing baseball with them and football—anything but having to go to that old dancing school all the time, just to correct her feet.

‘Nudged by fate’

Then there was that period in high school, she remembered, when she was forced to give up her friends and her teenage fun. Not that ‘forced’ was exactly the right word, Shirley knew—because, after all, nobody had pushed her into a dancing career at age fourteen. Maybe ‘nudged by fate’ was a better way of putting it. Anyway, at fourteen, Shirley remembered, she’d turned out to be a very good young dancer—despite all those years of not exactly liking it. And at fourteen, she remembered, she began appearing on television shows out of Washington, D.C., and at fifteen she found herself in New York City as a summer chorus replacement for one of the dancers in Oklahoma!, and at sixteen there she was back in New York again, this time spending her summer vacation dancing her way through Kiss Me, Kate and—

That was a time—boy, she thought now, as she stood there, still looking out the window, at the rain. Shirley MacLaine, big-time Broadway kid, former sorority president who didn’t have enough time for her sorority sisters anymore . . . Everybody in Arlington thinking, She must guess she’s pretty hot stuff by now! . . . But none of them realized that I would have given anything if I could have spent my summers at the beach with the other kids . . . That last year in high school, after Kiss Me, Kate, when I was offered a chance to dance in Europe and I said, ‘No, I want to go back to my home town and finish my senior year with the kids I grew up with, I want to have a normal year with my home town friends’—did any of these friends believe me . . . ?

Shirley remembered now the promise she’d made herself at the end of that year, when she graduated—that she would go back to New York, that she would work, that she would try to make a success of herself, but that she would never again allow this drive—implanted so deep inside her—to interfere with any personal happiness she wanted out of life. . . .

It was in New York, about two years later, when Shirley met Steve Parker and the happiest period of her life—before or since—began.

Partnership

She was a chorus girl—still.

He was a part-time actor who wanted desperately to become a producer someday.

Shirley fell in love with him, from the start.

Steve, a friendly but very reserved type, didn’t let on how he felt about Shirley personally. But professionally he let her know he thought she was terrific.

“Someday,” he would say to her, “I’m going to produce the finest picture ever and you’re going to be my star.”

“Me?” Shirley would laugh back. “I’m just a dancer—not an actress.”

But Steve thought differently. And after a while, he convinced Shirley to take dramatic lessons, to polish what he realized was a great natural talent.

Shirley took the lessons—until she tired of them.

Then Steve stepped into the picture, even more.

“I’ll teach you,” he said to her over the phone one day. “Do you mind if I come over to your place tonight after the show and give you a few pointers. . . ?”

So night after night, for the next year, Steve tutored Shirley in every phase of show business he knew. He taught her how to read lines, he taught her how to sing, he taught her stage poise, he taught her—most important—how to have confidence in herself.

It was work, lots of hard, tiring work.

But it was worth it to Steve, because he was helping build a talent he believed in.

And it was doubly worth it to Shirley, because she was learning so much and because at the same time she was able to be nee the one man on earth she really cared for.

“Me number-one student!”

Steve, still reserved, didn’t talk much about himself, before or after these sessions.

But when he did, Shirley was fascinated.

One night he got on the subject of Japan.

“I was born there,” he said. “I loved it It’s the kind of place, Shirley, where people would rather travel five hundred miles to see a sunset than go five blocks to find out about a used-car deal . . . In a way, I guess I look forward to going back.”

“Back?” Shirley asked, gulping. “You don’t mean back to stay or something, do you?”

“I don’t know.” He shrugged. “I’ve been thinking. I’m not getting anywhere as a producer here, that’s for sure. In Tokyo I stand a good chance of forming my own company—TV or movies, or both. Maybe—

“You’ll go then?” Shirley asked.

Again, Steve shrugged. “Probably,” he said.

Shirley tried to smile. “And leave me in a lurch?” she asked. “Steve, me number-one student. Need number-one teacher.”

Steve smiled back.

He bowed slightly.

“By the time I leave, Shirley, you will be number-one star—mark my words. . . .”

It was a little less than six months later—in the fall of 1954—when Shirley got her first fantastic break.

The show was The Pajama Game.

It was the third night after the opening.

A few hours earlier Carol Haney, one of the comedy stars of the new hit, had broken her ankle.

Shirley, her understudy, was told to go on.

Nervous, deathly afraid, she asked for a rehearsal.

No, she was told, there wasn’t any time.

“But I’ve never even had one—” she said.

No, came the answer.

Shirley rushed to a phone and called Steve.

“I need you, Steve,” she said. “Please come over and be with me now, tonight. Please.”

It won’t be easy

He arrived at the theater in ten minutes.

For the next half hour he simply talked to Shirley and calmed her.

Then he got hold of a script and cued her on her lines, still giving suggestions as to how to read them, how to say this, how to do that, how to make the audience laugh at you one moment and sympathize with you the next.

Finally, it was 8:40 and Shirley was onstage—and on her way to one of the brightest debut triumphs in recent Broadway history. . . .

The proposal came quietly.

It was two weeks later—a Wednesday. Shirley and Steve were having dinner and Shirley was telling about her meeting with director Alfred Hitchcock that afternoon, how he had caught the matinee, had liked her and had signed her to do The Trouble with Harry.

“Wow,” Steve said, “a contract with Hal Wallis last week, now a deal with Hitchcock.” He nodded, proudly. “I guess my job is done.”

Shirley knew what he meant, suddenly, just by the way he’d said it.

For a moment she didn’t speak.

Then she asked, “Are you going to Japan now, Steve? Has that deal come through for you?”

“Yes,” Steve said.

He looked away for an instant. “Actually it came through a couple of months ago,” he said, “but—I don’t know—I just wanted to stick around for a while.”

Then, quickly, he said, “Shirley, I know this may sound crazy—but will you marry me?”

“Steve—” Shirley started to say.

“I know, I know,” he said. “It wouldn’t be easy. You’d be here, doing what’s been cut out for you to do. I’d be there, thousands of miles away, doing what I have to do now. There’d be long periods when we won’t see each other, when we might wonder about what we’d done. But I love you and I want to marry you.”

“Shirley,” he said, “I—I mean—I guess I should have asked—how do you feel about me?”

“Oh darling . . . oh darling,” she said.

How long, how long, how long has it been since I’ve seen you, Steve? she asked now, half to herself, standing there at the open window. How long?

Everybody out there thinks that I’m the happiest girl alive tonight, she thought. And look at me.

She could visualize the success story about her in the paper the next morning when the Some Came Runningreviews were printed.

Suddenly Shirley remembered something Steve had told her the night he’d left, something she had almost forgotten.

“Baby,” he’d said—she recalled exactly how he’d said this now, how he had put both his hands on her shoulders and looked deep into her eyes, “Baby, I hope it’s only a few months this time. But no matter how long I have to be away, always remember one thing. I love you. There will be times when we’ll miss each other terribly. There will be times when it’ll be rough, on both of us. But remember—I love you. I told you that for the first time the night I proposed. I’ve told you that since. I’ll write it at the bottom of every letter I send you, every day. I’ll think it so loud you’ll be able to hear me. And remember it. It’s important. It’s as important when we’re separated as it will be when we’re back together, for good, some day. Remember it. Remember it well. I love you. I love you. I love you. . . .” The phone rang.

Shirley jumped up from the bed.

She lifted the receiver.

“Tokyo calling again,” she heard the operator say. “Go ahead, Tokyo.”

It was Steve. The line was clear this time, his voice strong. “Shirley?”

“Yes,” she answered.

“I’m sorry, honey. I miss you and Steffi so much, but I’ve been delayed,” he told her. “There’s been a production tie-up and I can’t get away right now. But I promise, I’ll be home in three weeks: Okay?”

“Okay,” Shirley said.

“You’re not too disappointed?” Steve asked.

“No,” she said.

“Shirley,” Steve asked, “—you’re sure? You sound as if you’re crying.”

“I am,” Shirley said, softly.

She smiled through her tears.

“I was just thinking how lucky I am to be married to you,” she said. “That’s why I’m crying, darling, that’s why. . . .”

THE END

Shirley is now in MGM’s SOME CAME RUNNING and can soon be seen in MGM’s ASK ANY GIRL.

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE MAY 1959