Sunday And Always—Esther Williams

One afternoon I plunged into our pool, and, after the impetus of the dive had spent itself, lay face down in a “dead man’s float.” No sound came to my ears, of course; supported as I was by the water, I had little sense of weight-or physical being. And with this came the thought of how perfectly I was isolated from the material world—a sealed-off privacy. A fancy struck me that I was in a sort of cathedral, a liquid cathedral, suspended between heaven and earth.

“This is my church,” I thought. “What a place to pray, to know one’s self thoroughly, and thus come to the door of God.”

To me there is peace in cool water, and there is beauty to the surface sparkling in the sun; to break from the depths out into the light. These are just impressions, I know, but when a person says that he or she sees God in beauty, and feels Him in peaceful moments (and I do), these, too, are impressions.

You never know when you are going to find yourself being led to contemplate the spiritual side of existence; it can happen anywhere and any time; for me a pool, for others a fox hole—or a classroom.

I remember my mother, a psychologist, telling me that she never thought she was undertaking anything of any religious significance when she started to practice her profession. Mother taught school in Kansas before she was married. To her it was a science she had studied in college (keeping her degrees up at UCLA after her five children were born!) which helped reveal man to himself according to findings which were well established but of no spiritual significance.

“But I was wrong,” she told me. “I discovered that if one really believes in psychology as a working force one cannot avoid the word of God in both explaining it and practicing it. God seems to be in our lives to stay. You get so far with science, sometimes very far, but never all the way without Him.”

The same thing is true of my work in the studio, I guess. For instance, one morning, some months ago, I was called to the office of Mr. George Sidney who was to direct me in my latest picture, Jupiter’s Darling. I figured that some technical problems had come up. I walked into the conference prepared to breeze right on through whatever the trouble was. But when the talk was over I was in as thoughtful a mood as I have ever been because I had a really intriguing assignment—to become a new kind of Esther Williams!

Oh, I’d be the same girl in many ways, but it was necessary that I take on new dimensions in guess what! Femininity! I’d better explain—or let Mr. Sidney do it.

“So far in your pictures you have always been the American go-getter type of girl,” he told me at the conference. “You see the man you want. You make plans. You launch a direct attack. And you win in this manner. But this time we are dipping into ancient history to show a woman whose ways were more subtle, a woman who wins by seemingly losing, by yielding. And yet, by so winning, conceivably also loses! It is for each woman in the audience to tell which, by the prompting of her own experience.”

Jupiter’s Darling, you may know, is based on Robert Sherwood’s hit play, The Road To Rome. It concerns the perplexing failure of the great warrior, Hannibal, to attack and sack that city after crossing the Alps and finding it at his mercy.

According to Sherwood’s play, Hannibal was dissuaded by the feminine logic, not to speak of feminine presence, of Amytis, wife of the then dictator of Rome, Fabius Maximus. Amytis had somehow managed to make her way to Hannibal’s camp and into his tent, and had also somehow managed to make him forget his war plans. It was with that second “somehow” that my role was concerned.

This was very interesting, but also a little bit worrisome. Any time anyone wants to give old Esther a crack at this deep, under-the-skin acting she is intrigued. But she’d also like to make sure of doing a good job. Here was a role that not only required hard study, but also a psychological knowledge and understand|ing of the character (we’re back to my mom again). So I went looking for this girl Amytis . . . rather, I went looking for the kind of reading that would conjure her up for me. And where do you think I found her? Well, good bits of her were in the Bible in the book of Esther. And insights into her ways and kind of thinking were in other philosophical works, including Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet.

“And think not you can direct the course of love, for love, if it finds you worthy, directs your course.

“Love has no other desire but to fulfill itself.

“But if you love and must needs have desires, let these be your desires:

“To melt and be like a running brook that sings its melody to the night.

“To know the pain of too much tenderness,

“To be wounded by your own understanding of love;

“And to bleed willingly and joyfully.

* * *

“And then to sleep with a prayer for the beloved in your heart and a song of praise upon your lips.”

When i read these words of Gibran’s I was beginning to come close to the sacrificial nature of a woman in love, and not only that, but I realized how near such ways are to the sublime theme of love in religion. That’s what it took to get me in the frame of mind necessary to feel I could be an Amytis!

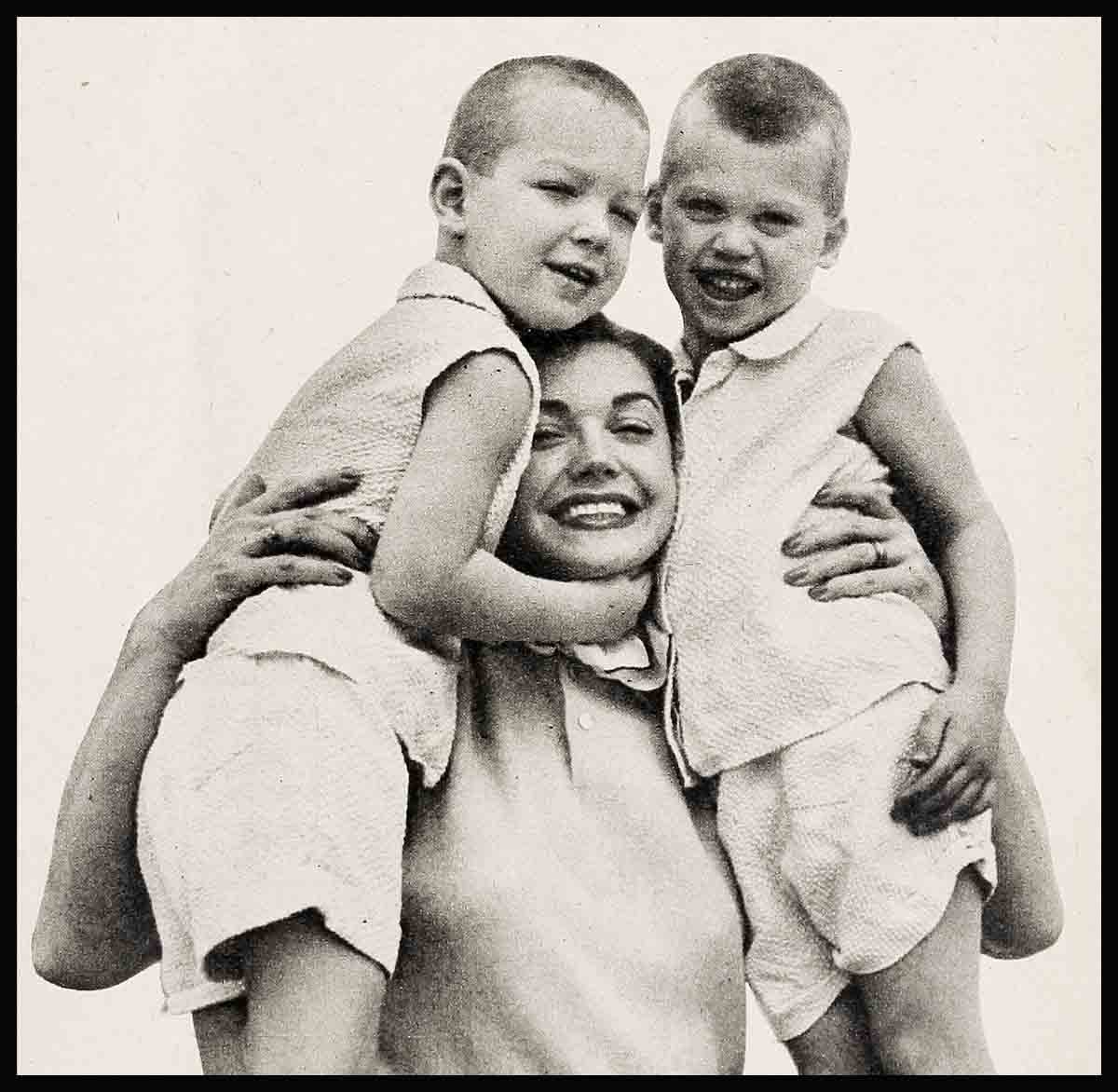

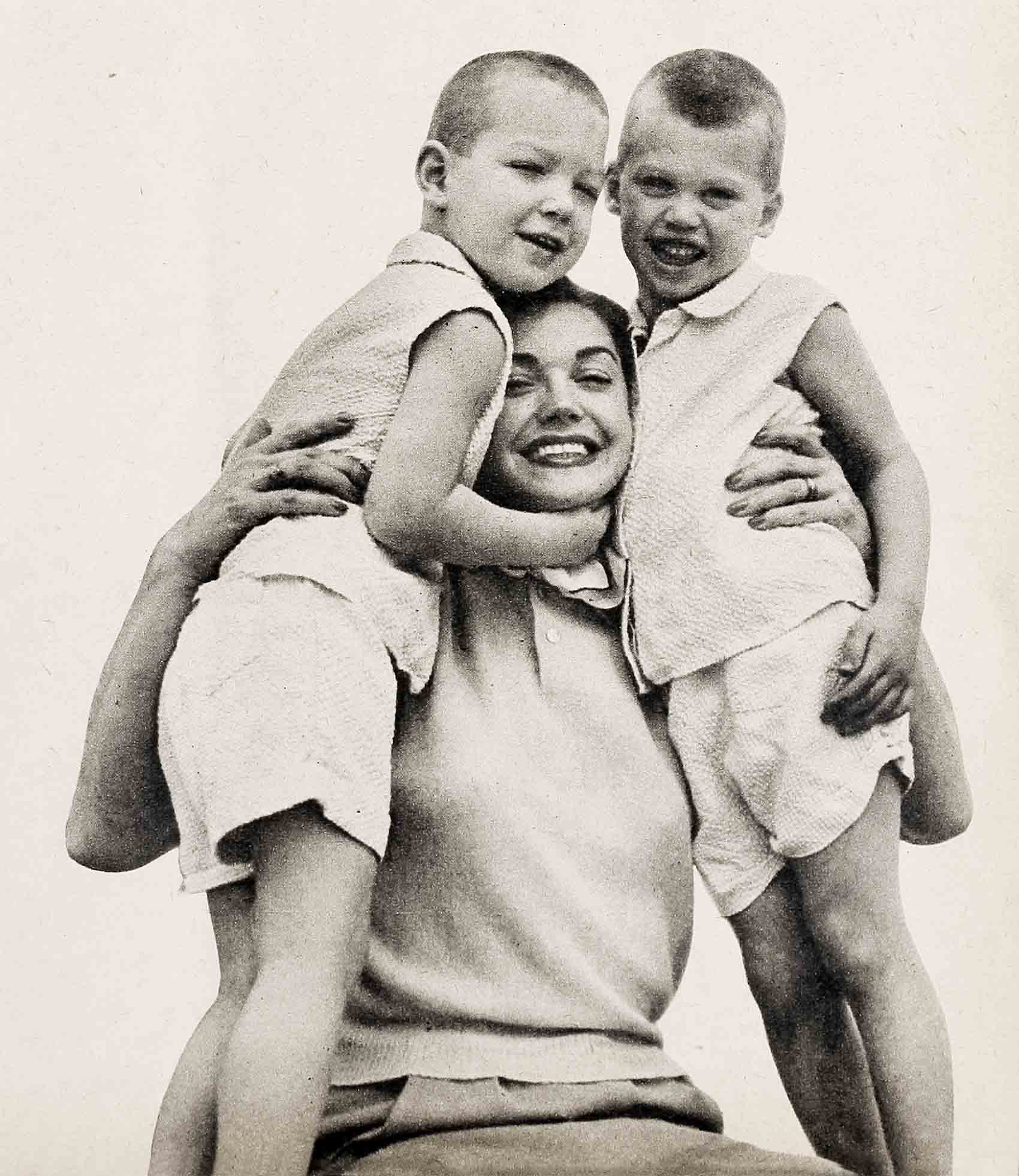

It’s funny but I sometimes think that what adults have to study to learn about their spiritual world, most children often know instinctively. When my oldest boy, Benjie, who is not yet five, was heard saying not long ago that there was more to the world than his mommie and daddy, I knew he meant he had experienced already the feeling that there was a higher force, a mysterious guiding Something. I was not surprised. In talking to him I had seen this belief coming to life in his eyes.

Of course this God of Benjie’s is a child’s God; I can tell by the trust in his eyes that there is no wrath to this God—only love and sunlight and warmth. This is the same God I know, but I didn’t get to Him until my childhood was over. This doesn’t mean I never received religious training when I was young. I can remember hearing my first stories about the Bible when I was two. But no impression was made upon me then.

Today I feel that the faith I have never happened to me—I happened to it. I had to think and feel my way to it. On the way to the satisfaction of coming into belief there was a period when I had nothing. But I don’t think of this as a time when I was an agnostic or an atheist; rather I recall it as a time of wander and wonder. I remember in my early teens crying out to my mother of my perplexity.

“Do you know I don’t believe in anything?” I asked. “I just don’t believe. Like being in a vacuum. What shall I do?”

Mother showed no alarm. “Do?” she asked. “Nothing. You are already growing into belief. You have become the kind of person who must reason her way to something as well as feel it. Now you are in an intermediate stage, but you’ll come to what you want, to what you feel you need.”

I did. There was no great revelation. Faith came bit by bit, rubbed off on me, sort of, when I knew or touched goodness. It is still coming to me and, I honestly think, more through the everyday things of life than through formal seeking. And because this is so I have for the last few years been convinced that mine is a work a day religion.

It shows no preference for Sundays but can make me aware of its presence at any time; as strongly when I am on my feet as when I am on my knees, as greatly when I sip a cup of coffee as at a time when my children are being christened.

Don’t let me take away from the power of such moments as one experiences in deep devotion at one’s church; I value these as much as anyone. But I would no more divide life into faith and non-faith periods, or even strong-faith and weak-faith periods, than I would divide myself into devout and non-devout parts. I mean that if I am close to the true spirit when I am saying my amens in church I must also be as close to it in as seemingly pagan a place as a nightclub if there I am doing a Christian deed for someone. Wherever man helps man the Lord is being praised.

Since I have brought my mother into the cast of characters of this article in a prominent way maybe I should say a direct word about her. As far back as I can remember she was always a figure surrounded by books; books all over the house; in the parlor, in her bedroom, even at her side when she worked in the kitchen. But she never gave of her learning to us as mere learning, as so many facts, but always as a way of living.

Mother is the same person today that I have always known her to be—a highly useful person. Working with three other psychologists she has a counseling service which is operated without thought of profit. To pay for the expenses of their group they make a charge of as little as one dollar and never more than five dollars.

Mother has never been too busy to be a mother to me, even today, but she is too busy to be my fan. Her work is as important to her as my work is to me—maybe I should say more so when I think of how serious she can be and how I, sometimes, cannot. And when she thinks of her children, she thinks of all of them on an equal plane. So I’m never surprised when people ask her if she isn’t proud of me, and she replies that she is, but that she’s proud of my two sisters and brothers, too. She never has appeared bowled over about my career. Then, one day, she spoke on this subject in a different tone.

The place was the Westwood Hills Congregational Church in Los Angeles. The occasion was the christening of our three children, Benjie, Kim and Susan. (Being the disorganized me that I am, the christening was done at one time on a wholesale basis.) When Mother kissed me her first words answered the old question.

“Yes,” she said (and for a moment I wondered what she was starting to say), “today I am really proud of you!”

That’s mother. She was not so much impressed by the success of my professional life as she was by success in my personal life. I think she has a very mature attitude and one that I have adopted to serve me through the years in matters of faith as well as in matters of family.

It is important to recognize what is important and what is not. To believe is important, when how you believe may not be. I am struck by an illustration that may seem rather light but makes sense to me. Maybe it will to you:

A fellow asks you for a date. Then before he arrives he sends a corsage. The corsage is fine, of course. It shows you that he considers the date important and does things properly. But the main thing is getting asked for the date. A date without a corsage is still a date. A corsage without a date—well, it’s just a decoration.

My spiritual date in life is with God. Wherever I can find Him, or wherever I can find signs that attest His presence and His goodness, I will go. This may be in my church, or it may be in another church, using this or that form of approach. He is in all churches, I believe, and from all I borrow to know more about Him and His ways. Only this is important.

Two lines from Alexander Pope’s Essay On Man say all this much better:

“All are but parts of one stupendous whole Whose body Nature is, and God the soul.”

THE END

—BY ESTHER WILLIAMS

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE JANUARY 1955