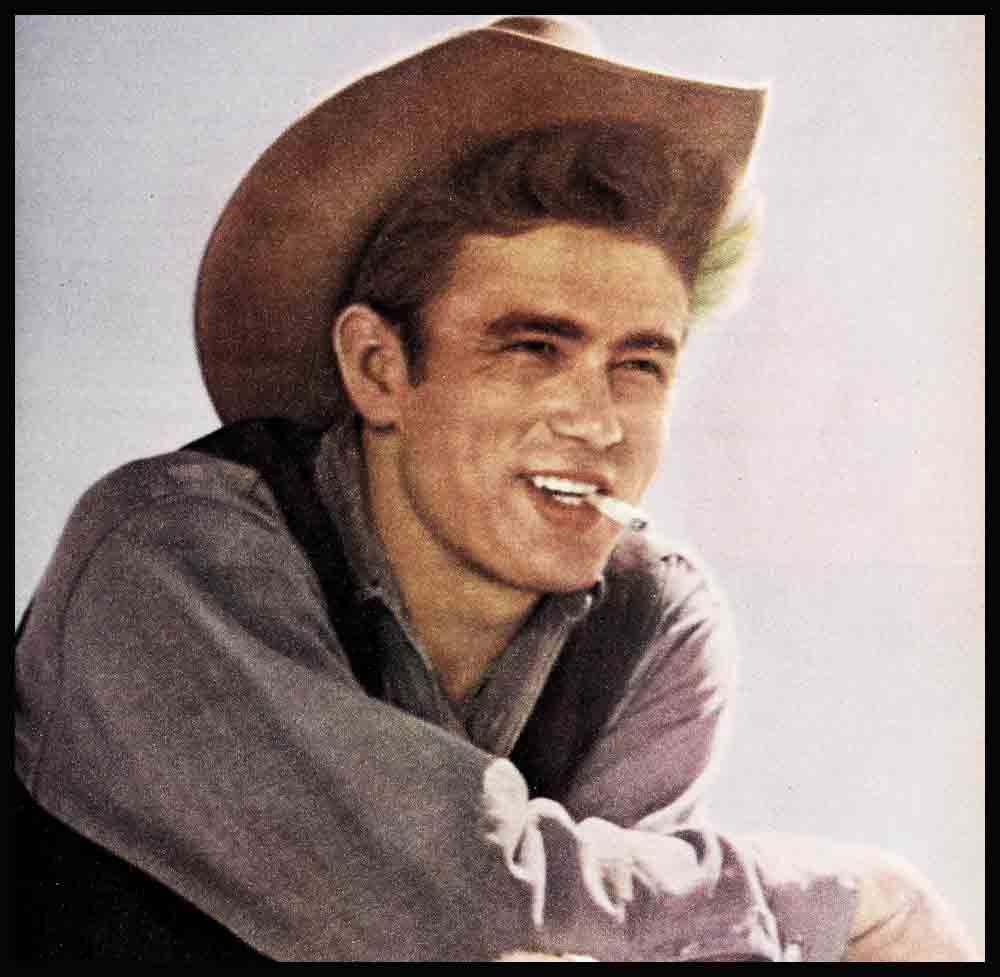

There Was A Boy—James Dean

PART I

Editor’s Note: William Bast, a native of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, is now a TV script writer who makes his home in New York City. He was majoring in Theatre Arts, with the aim of becoming an actor, when he met James Dean.

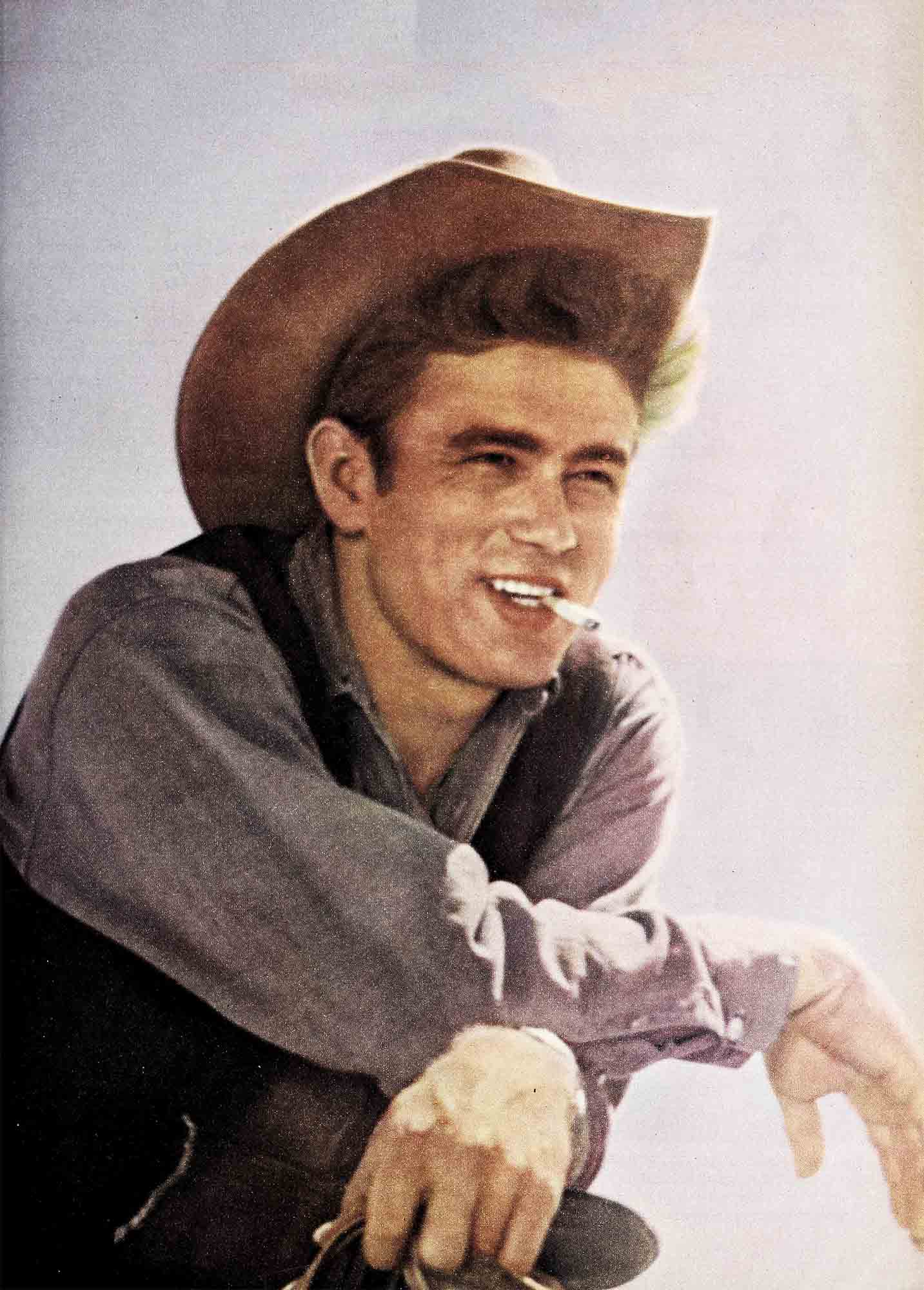

On September 30, 1955, the world was informed that the short but incredible career of James Dean had come to a tragic end on a lonely northern California highway. One year prior to that date James Dean was a comparatively obscure actor and was hardly known to the public. Now, almost one year after his death, he stands on the threshold of immortality.

James Dean’s life was by all means filled with excitement and turbulence. It is the fascinating tale of a young man who propelled himself violently through a few short years, in search of fulfillment, love, and understanding. It is a legend filled with the profundity and gentleness that was the boy himself.

Jimmy was my closest and most constant friend during the six years before his death. Most of that time we shared the living expenses involved in the struggle to gain recognition in the theatre, and we were seldom out of touch with each other. In my peculiar position of having known him so long and having shared so many experiences with him, I find it hard to comprehend the full significance of what happened to the school chum I came to call my friend. Just three years ago he was just my crazy roommate who, like all the kids we knew, was trying to make a mark for himself. He was known only to a limited group of people and his name meant nothing to the man on the street. Now, there isn’t a day that goes by that I don’t hear his name on the lips of some stranger passing on the street, that I don’t hear stories of how many of his fans are still writing letters of devotion to the Hollywood columnists, that I don’t see his picture in the window of some store in a small town, that I don’t see his name headlining the double feature at a neighborhood movie house, that I don’t feel the strong and memorable impression he made on the people who knew him, worked with him, or admired him. I still find it hard to believe that they are all referring to the same Jimmy Dean I knew so well. Perhaps, I often think, they are referring to the Jimmy Dean they came to know only briefly, only partially, on the screen, on a sound stage, or in a rehearsal hall. And perhaps, I wonder, it isn’t the same Jimmy Dean at all.

In 1949, the Theatre Arts Department of the University of California at Los Angeles was a busy place. Stage productions were at a peak. The acting, it seemed, had never been so fine. World War II had ended a few years before and the departmental heads were enthusiastically utilizing the more mature talents of the many recently returned Gls. Unfortunately, the younger students who hadn’t participated in the war, and who hadn’t as yet matured, were being sidestepped. The gap of years between the regular students and those on the GI Bill created cliques within the drama department.

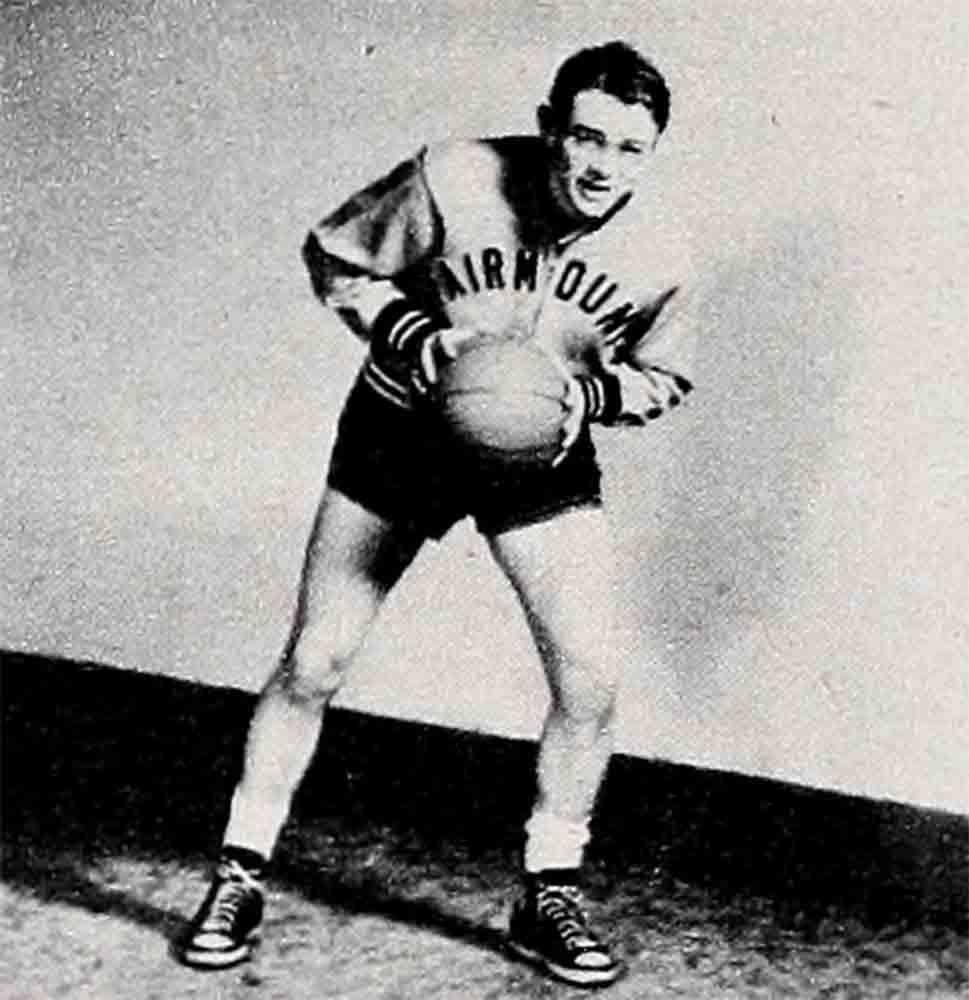

In this atmosphere, the slouched, unimpressive figure of James Dean drew no attention. The sandy-haired boy, completely withdrawn behind his horn-rimmed glasses, was a new student who had just transferred from Santa Monica City College. His major was Law and his minor was Theatre Arts. He had been pledged to Sigma Nu fraternity and was “living in” near the campus. He had some knowledge of motion picture projectors and, with the help of the campus employment agency, was able to bear the financial burden of fraternity and college life by acting as projectionist for classes using visual education. His clothes were few and modest, and his manner was mild and unnoticeable. He did not mingle freely and, as a result, did not become a part of any particular clique. It was impossible for him to make friends with these people who were so impressed with their own self-importance, as he later put it. So he withdrew from the society of the Theatre Arts Department and tried very hard to fit in with his fraternity brothers. Jimmy was not happy at UCLA.

The department was doing a production of “Macbeth.” Somehow, Jimmy had been cast in the role of young Prince Malcolm. One night, during a late rehearsal, I was introduced to him in the Green Room—which, in theatre circles, is a gathering place backstage, sort of a reception room where actors get together before or after a show. As I recall, Jimmy made no impression on me at all. He was quiet, almost sullen, and seemed to resent the fact that he had been asked to work in the show.

When “Macbeth” opened and started its two-week run, the reviews in Spotlight, the Theatre Arts Department’s newspaper, were not kind. As for Jimmy’s performance, it said only, “Malcolm (James Dean) failed to show any growth, and would have made a hollow king.” It was true that Jimmy’s acting was not good. His Indiana twang made Shakespeare’s immortal lines sound more like they had been written by Mark Twain and were being delivered by Herb Shriner. It was obvious that James Dean was not one of UCLA’s outstanding acting talents. As a matter of fact, it seemed that it would have been wise for some close friend to advise him to forget any theatrical aspirations. No, indeed, James Dean just didn’t have it—not then, at any rate.

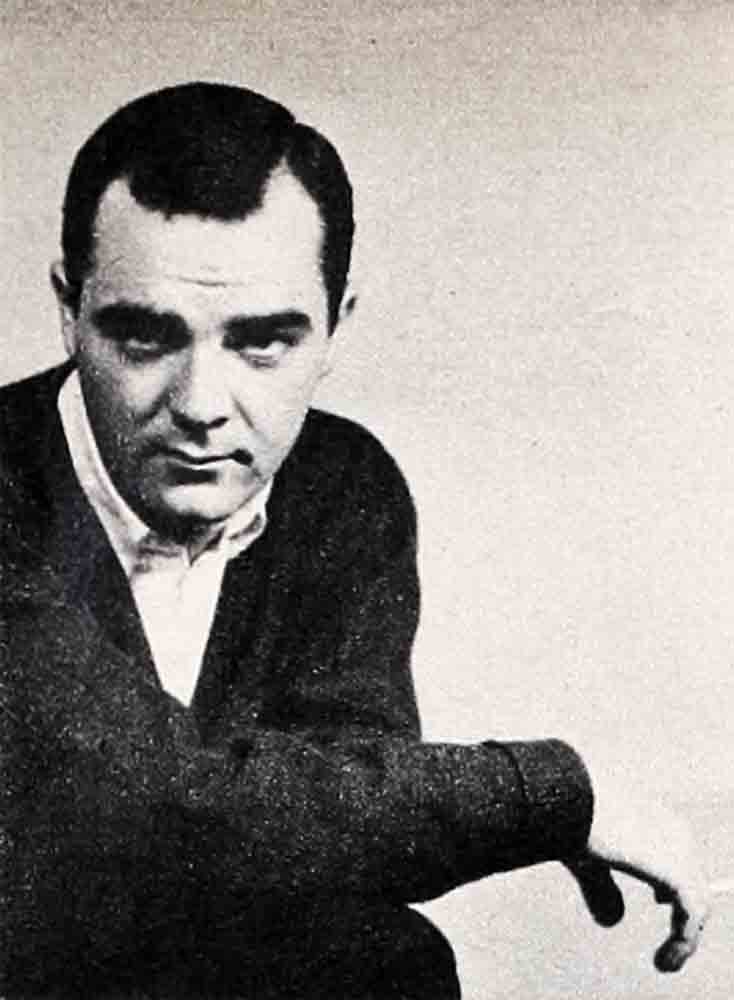

Among some of the more dedicated actors on campus, there was a feeling that UCLA was not providing enough in the way of acting guidance and training. The regular classes were considered totally inadequate, in the light of the upsurge of a “new school” of acting that was emanating from far-off New York. I had briefly met James Whitmore, who had just won an Academy Award nomination for his acting in “Battleground.” Noting the dissatisfaction on campus, it occurred to me that Whitmore, a graduate of the Actor’s Wing in New York, might be able to solve our problem.

Whitmore, himself, had found that Hollywood was completely lacking any type of acting school in which he could continue his studies and was, as a result, greatly interested in such a project. He suggested that I invite eight or nine people from UCLA whom I felt would be seriously interested in pursuing their drama studies more intensely. He insisted, however, that we were not to consider him a teacher, but merely someone who was there to guide us and learn with us. As carefully as possible, I selected the students whom I felt would most appreciate and benefit from this advance training.

During the UCLA run of “Macbeth,” a Hollywood agent saw Jimmy and approached him with the proposition of representing him. The idea of an honest-to-goodness agent, regardless of how unimportant he was, believing he had a potential, so flattered Jimmy’s ego that he decided it was an actor’s life for him from then on. This new dedication, coupled with the fact that Jimmy and I had become good friends, convinced me that he should be invited to join the Whitmore class.

Jimmy completed the group of nine. We began to meet several times a week in a room above the Brentwood Country Mart. The first meeting found us all tense and anxious. An air of quiet excitement hung over the group. We were about to hear the magic words that would reveal to us the secret of acting. It didn’t take Whitmore long to dispel all that nonsense and plunge us headlong into serious and intense study. So, listening attentively, and reading faithfully from our copies of Stanislavsky’s An Actor Prepares, we waited for something to happen.

About this time, Jimmy confided to me that he was finding it increasingly difficult to tolerate his fraternity brothers. It seems they suffered from the slightly dated and provincial attitude that there was definitely something wrong with anyone who was interested in the theatre. Considering Jimmy’s hyper-sensitivity to the subject, it was no wonder that he was rubbed the wrong way by the jibes of a fraternity brother one night during a stag party. Jimmy took the snide remarks as an insult and the affair ended in a fist fight. It was with mutual sentiments that Jimmy and his fraternity brothers parted company. Since both of us were then in search of living quarters, we decided to combine forces and find a place together.

Eventually, we found a three-room apartment which had been constructed on top of an apartment building near the beach in Santa Monica. It was artfully done—a place, we felt sure, where budding young artists could grow. Although it was too expensive for our limited budgets, we were unable to resist its charm, and so we moved in.

“The Penthouse,” as we called it, was the scene of Jimmy’s intellectual awakening. Living in such close quarters, it didn’t take me long to discover that my friend was greatly lacking in plain old everyday knowledge. It was amazing how little he actually knew about art, literature, music, history, politics, and the like. I think it was the excitement over the Whitmore acting group and his new agent that made Jimmy want to start learning more about everything. He wanted to be completely prepared for anything life might present. He had often expressed a desire to grow intellectually, to broaden his scope of understanding, but had never actually started on an all-out campaign.

We would read, sometimes to each other, then we’d discuss what we had read with other members of the group or with friends. Sometimes, with our girls, we would read from Stanislavsky, Henry Miller, or Kenneth Patchen. Jimmy tried very hard to perfect his diction by reading aloud from various plays, acting out every part himself. He kept a dictionary at hand to look up any word he didn’t know.

So it went for several months.

Those were the lean months. Jimmy had no income, and I was barely able to scrape together enough for food and rent from a part-time job as an usher at CBS. Somehow we managed, in spite of the fact that our combined resources rarely exceeded $30 a week. Each month, when rent time rolled around, there was a scramble to gather together the few dollars that people owed to either of us and to borrow whatever we were lacking.

When we first moved in, the electricity had not been turned on and we were forced to use candlelight for several nights. However, the effect was so pleasing, we decided to dedicate at least one night a week exclusively to the use of candles. Thus we had the inspirational effect of candlelight and, at the same time, saved on our electricity. Sometimes on “Lightless Fridays,” a group of us would lounge around the apartment, listening to classical music and learning to identify the selections. The mood was warm and friendly, and there was always the feeling that something important was happening to every one of us.

Food was very often a serious problem. I remember once, shortly after we had paid the rent and we were both flat broke, sitting down to a dinner consisting of dry oatmeal mixed to taste with mayonnaise or jam. One successful scheme we used to keep from starving was to invite several friends up for dinner, then pool the few pennies we all had, and prepare rice or spaghetti dishes. Times were hard, but fortunately we were able to keep laughing—at least most of the time.

However, Jimmy was subject to frequent periods of depression and would slip off into a silent mood at least once a day. During these periods, I found it impossible to communicate with him, and I soon learned to ignore him or avoid him completely. Sometimes he would sit quietly thinking for hours; other times he would read or draw, making only occasional grunting noises when a question was put to him. Very often he would take long walks late at night, mostly to the amusement pier in Venice, a few miles away, where he would watch and study the people. But, invariably, he would snap to after a few hours and never acknowledge the fact that he had caused anyone concern or offense. Jimmy’s moods ended as abruptly as they started.

It must have been an act of God that made my mother decide to pay me a visit about this time. When she arrived from the East, we invited her to stay with us in our modest quarters. Her arrival was like a ray of heavenly sunlight. As soon as she saw our barren larder, she headed for the local supermarket where she bought everything in sight. She cooked sumptuous meals for us and saw to it that the apartment was clean.

Jimmy liked Mother at first, but soon he became uncomfortable. He was always embarrassed when people did things for him. He disliked the feeling of obligation that goes with the acceptance of a favor. He knew he was in no position to repay her with tokens of kindness or appreciation. He hadn’t matured enough to realize that her payment came in the form of seeing him well-fed, clean, and happy.

One rainy day, Mother decided to stay in, clean the apartment, and fix a fine dinner for that evening. Jimmy also remained in the apartment the whole day. When I returned from work that evening, I found Mother in tears. Jimmy, it seems, had spent the entire day working sullenly on a mobile he was constructing. He had not spoken to her all day and had only grunted in response to her questions and attempts at conversation. It was all very upsetting for Mother, who didn’t even know what the crazy thing was Jimmy had been building. She had not experienced his moods before and was under the impression that she had offended him. Jimmy didn’t seem to feel remiss, nor did he apologize. Instead, he slumped into his chair at dinner and shoveled her carefully prepared meal into his mouth with boorish abandon. During the remainder of her visit, Mother avoided staying in the apartment alone with Jimmy.

When she left, we drove her to the depot. While she was checking her lug- gage, Jimmy disappeared for a few moments. When he returned, he presented her with a box of candy, for Mother’s Day, which he had bought with his last dollar. Included with the gift was a photograph of himself which she had admired. He had signed the picture: “To my second mother—Love, Jimmy.” Knowing that his mother had died when Jimmy was only nine, Mother was deeply touched, although somewhat confused by his seemingly sudden switch in attitude. It wasn’t until a few years later, when I explained that it was simply Jimmy’s nature to be moody and that he had really liked her very much, that she understood. Neither of us knew then that she was to be the first in a series of “second mothers” for Jimmy.

Up to that point, the only job Jimmy’s agent had been able to get him was a television commercial in which he danced around a jukebox with a girl and another boy. He got $30 for that first professional job, and didn’t talk much about it. The money didn’t last long and, after several weeks of waiting and hoping for something else to come up, Jimmy took the situation into his own hands. He went back to the studio where the TV commercial had been filmed and asked if there was anything else on the fire in which they could use him. He read for them and was assigned a role in a full-length television feature. He was to play young John, the Baptist, in an Easter film called, “Hill Number One.”

About a week before he was to start the film, while in the Whitmore class, Jimmy suddenly seemed to get the message—the “golden secret”—which, I feel, started him on the road to becoming a true artist. Jimmy and I were doing an impromptu scene, set up by Whitmore. Secretly, Whitmore told me I was to play a jeweler who had repaired a watch Jimmy had brought in and I had since learned that the watch was stolen. It was my job to detain Jimmy until the police could arrive. Jimmy was told, without my knowledge, that he must get the watch at any cost and catch a train out of town in ten minutes in order to avoid being caught by the police.

We tried the scene several times, but it was flat and uninteresting. Each time, either I gave the watch to Jimmy, or he left without it, neither of us putting up much of a fight. Whitmore finally stopped us‘ and talked about the singleness of purpose in a scene such as this and how one could achieve that attitude through intense concentration. He spoke of a type of concentration we had never imagined possible. His explanation seemed to hit Jimmy right where it was supposed to.

We tried the scene again. At first, the noticeable change that came over Jimmy was almost frightening. With grim determination he set himself to the desperate task of getting that watch. Nothing else in the world mattered to him. The more he insisted, the more I refused. The more demanding and insulting he became, the more emphatic I became in my refusal. The fist fight that resulted had to be broken up by Whitmore and the others.

When it was over, Jimmy and I were both amazed, and we felt refreshed, as though we had just been given a shock treatment. From that moment on, everything he heard, everything he read, everything he did seemed to have new meaning for Jimmy. Until then he had understood everything, but now he was able to apply it. For the first time, acting made sense to him.

Jimmy carried this newly acquired understanding with him into the filming of “Hill Number One.” When the picture was released on television Easter weekend, the reviews of his acting were filled with praise. His agent had contacted several producers and asked them to watch the film. They were impressed with Jimmy, but, as is so often the case, that was as far as it went. Jimmy had hoped for more than praise and he was terribly disappointed when the jobs didn’t start rolling in. After all, he insisted, shouldn’t an actor who has proven his worth be employed? He still had to learn that this is one of the most heartbreaking aspects of the acting profession.

Before long, Jimmy was out of money again and needed a job. I was still working as an usher at CBS in Hollywood and, after much persuasion, I was able to convince my boss to hire Jimmy. Although he had taught sports at a small military academy near Los Angeles one summer, Jimmy found it impossible to conform to the regimentation of an usher’s life. He resented wearing the uniform—the “monkey suit,” as he called it—and refused to take the directives of the head ushers with appropriate seriousness. As a result, unprecedented as it was at CBS, Jimmy was released after one short week, during which he had managed to provoke the wrath of every one of his superiors. After that, I just smiled blandly when they would sneeringly refer to him as “your friend, Dean.” Having committed the unpardonable sin of introducing the corruptive influence of James Dean into the orderly, well-organized pattern of the CBS machine, I had to remain constantly on guard, lest I make another dreadful mistake. Jimmy accepted his dubious notoriety with devilish glee and gracefully lapsed into a status of being unemployed.

He began dating Beverly Wills, daughter of the noted commedienne, Joan Davis. I had introduced them at CBS, where Beverly was acting on the radio show, Junior Miss. They soon found that they had a great deal in common, mostly their love for sports, and started spending much time together. Beverly introduced Jimmy to the world of young Hollywood, where he found new interests and excitement in meeting and getting to know up-and-coming stars like Debbie Reynolds. However, there was one serious flaw in the relationship, Beverly’s mother. Jimmy’s lack of social grace and his candid frankness unnerved Joan Davis so much, there was constant friction between them. It soon became apparent that Jimmy’s relationship with Beverly was destined to be short-lived.

Going with a girl like Beverly made money more important to Jimmy. He was forced to take a part-time job parking cars in the lot next to CBS. Since his hours were irregular and flexible, he was able to search for acting jobs on the side. Most of the CBS radio directors and producers parked their cars in the lot, and Jimmy soon got to know them. Eventually, one or two of them discovered he was an actor and decided to give him a chance on their shows. He did a few bit parts on several dramatic radio shows and even got a walk-on in one Alan Young TV show. He also arranged for interviews at the major studios, through a friend who had done some bit roles in movies, and managed to snare bit parts in “Sailor Beware, starring Martin and Lewis; “Has Anybody Seen My Gal?” starring Rock Hudson; and “Fixed Bayonets,” starring Richard Basehart.

In spite of the jobs he seemed to be getting. Jimmy was dissatisfied and impatient. The Whitmore classes had adjourned for the summer, he had broken off with Beverly, and he was becoming increasingly restless. His personal life didn’t seem to have any order. He had recently met several established actors and directors, such as David Wayne and Bud Boetticher, whom he found intellectually stimulating. Their strong influence on Jimmy prompted him to delve even deeper into the realms of the abstract and the esoteric. What he found made him eager for more and greater sources of truth and wisdom. Hollywood didn’t hold the answer for him and he knew it. He wanted to soar, but he didn’t know how.

A great boredom set in. Through some of his newly acquired friends, Jimmy was introduced to the plush life on Sunset Strip. He had little to do but loll around the pool at the Sunset Plaza where some friends of his were staying and make clever talk with the “Strip Set.”

It would be completely wrong, however, to say that Jimmy did not grow during this period. He was an attentive listener and had a tenacious memory. He picked up a great deal from the people with whom he was associating, and he made it a point to study in detail any subjects they discussed which were unfamiliar to him. In an amazingly short time he became well-versed in the subjects of modern art, contemporary literature, and progressive classical music. But, the shallow veneer of Strip life eventually wore thin, and his boredom grew and grew. There was more than this waiting for James Dean and, somewhere in the back of his mind, he knew it. That was the reason he made the decision that was to change the pattern of his life so radically.

Next month, Bill Bast will tell of Jimmy Dean’s move to New York, of his intense struggle to find acting jobs, the new, influential people he met, and the little-known facts behind the events leading up to the biggest break of his career.

Part Il of “There Was a Boy” in October Photoplay On Sale September 6

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1956

graliontorile

19 Haziran 2023I loved as much as you will receive carried out right here. The sketch is tasteful, your authored material stylish. nonetheless, you command get bought an nervousness over that you wish be delivering the following. unwell unquestionably come further formerly again as exactly the same nearly very often inside case you shield this hike.

vorbelutrioperbir

17 Temmuz 2023You made some good points there. I did a search on the subject matter and found most individuals will agree with your website.