Who Needs Beauty!

By Hollywood standards—and one must never, never minimize Hollywood standards!— Audrey Hepburn is flat-chested, slim-hipped and altogether un-Marilyn Monroe-ish. Her measurements are: bust, 32“; waist, 20 ½“; hips, 34. Nothing sensational there, is there? And yet. Hollywood standards or no, Audrey Hepburn is the most phenomenal thing that’s happened to the film capital since Marilyn Monroe! Figure that out and you’ve got the answer to what makes Hollywood tick.

I met this new sensation in her dressing room at Paramount—it was once Dottie Lamour’s dressing room, when Dottie was Queen of Paramount—on the smoggiest morning in the history of Los Angeles. It was also the morning when the critical reviews of “Roman Holiday,” Audrey’s first picture for Paramount, were just starting to break in the newspapers. The reviews were unanimous in hailing the performance turned in by this gamin from across the seas with surprise and delight.

My eyes were watering. The smog was a fiendish mixture of fire, brimstone, hatpins and feathers. Then Audrey Hepburn glided into the room and the cloud lifted and my eyes stopped watering.

She’s exactly five-feet-six-and-three-quarter-inches high in her stocking feet, and she moves those five-feet-six-and-three-quarter-inches around a room like a cat—gracefully, proudly, a trifle arrogantly—and you sit up and take notice because her arrival is like a blare of trumpets. This is an actress in the grand manner: another Garbo, Bette Davis, Katie Hepburn, Greer Garson, Joan Crawford or who-have-you? This is if!

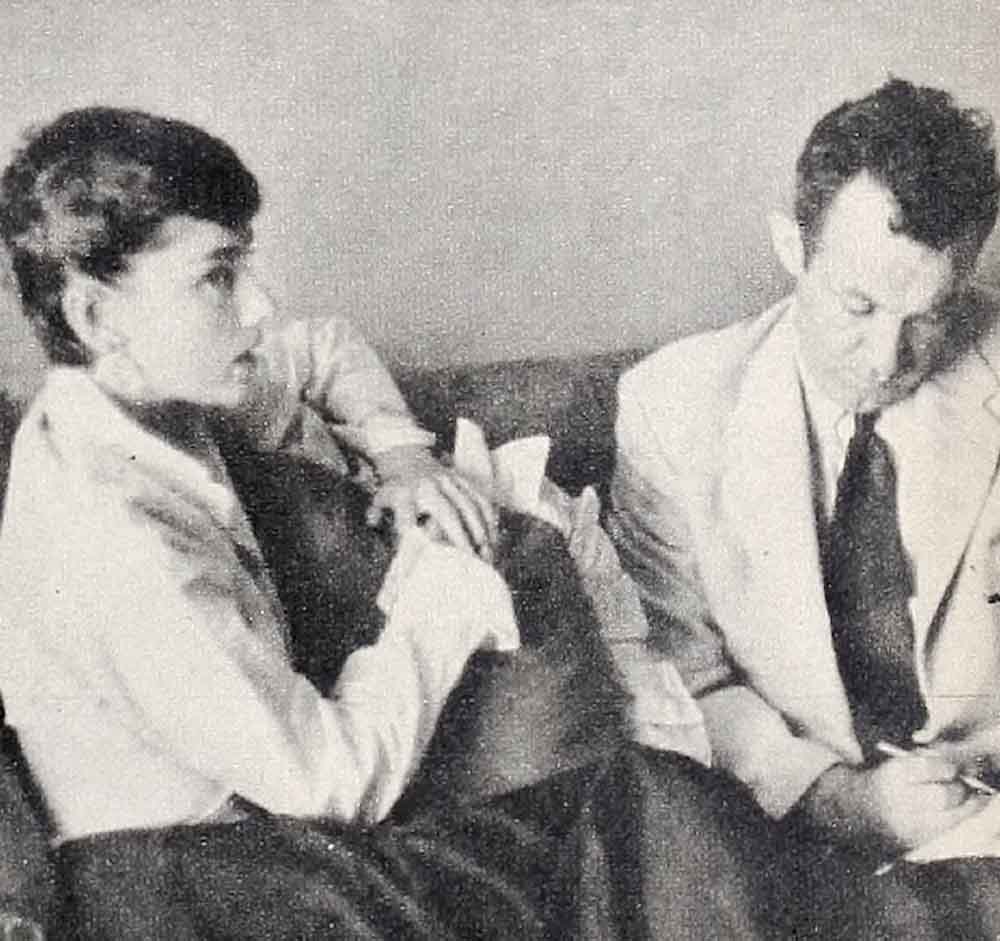

I had come prepared to ask her about the rumors linking her name romantically with Gregory Peck’s, her co-star in “Roman Holiday,” plus a lot of other personal questions. Instead, I sat and let her talk, mesmerized by that exquisite little-girl face. those hypnotic eyes exquisite gamin face, those hypnotic eyes, the most expressive dancer’s hands since Renee Jeanmaire’s, that smile like a rainbow after a summer shower. I thought: I should be more blase about meeting actresses—after all, I do see and talk to so many of them on my rounds of the studios and the Sunset Strip salons!—and yet here I sit staring like a hick from Hicksville, and straining to hear every word Audrey utters in that thoaty, highly mannered half-Dutch, half-English voice, afraid to miss even a fleeting expression in those constantly moving, uptilted eyes.

Rosemary Clooney, a Paramount dazzler in her own right, had told me how shaken she had been when she first met Audrey: “It happened to me only once before, the day I met Bing Crosby for the first time. I had seen ‘Roman Holiday’ and was frightened to death at the prospect of meeting such a great artist as Miss Hepburn. And then, all of a sudden, we were being introduced! I wanted to tell her how much I had enjoyed her work in the picture; instead, I was so nervous I couldn’t talk. I actually stumbled—and then I fell out of the door of her dressing room!”

Well, I was feeling that way too. But despite my ill-concealed awe, I went to work with a few questions.

First of all, what about the Peck story? Audrey’s eyes twinkled and then she rubbed them and said, “So this is smog! Golly, the fog in London never affected my eyes like this.”

I persisted: “You must have read the columns and noticed how they’ve been linking your name with Peck’s.”

She grew serious. “Yes, I know all about those stories. Who starts them? And how could they be true, especially when I’m so friendly with Gregory’s wife, Greta? I saw her coming out of Romanoff’s the other day, and she asked me to spend next Sunday swimming in the pool at her home. Does that sound like I’m a home-breaker?”

I agreed that it didn’t and then asked, “When is Greg coming home from Europe?” She said, “I really don’t know.”

I asked her to describe her first meeting with Peck and to tell me what she thought of him. Her eyes lit up as she replied: “I first met Gregory just before ‘Roman Holiday’ started shooting in Rome. It was at a little cocktail party that Paramount gave for the cast and crew before the picture rolled. My first impression of him? Well, it’s awfully hard for a person to talk about movie stars, especially one as big as Gregory Peck whom I had seen and admired in so many movies. But I remember thinking, ‘He’s even better-looking off the screen than on!’

“I might have said hello to him when we were introduced—I think I did, as a matter of fact!—although there were so many people standing around talking I can’t be sure. It seems to me now that I couldn’t speak at all, as though I were tongue-tied. It was just too much. You must remember that I had just arrived in Rome and here I was making a movie with a great star like Gregory Peck and a great director like William Wyler—oh, well, it was just more than I could bear!

“I must say, though, that I was enchanted with Gregory”—she seemed to caress the name as she said it—“because he was so marvelously normal, so genuine, so downright real! There’s nothing of the ‘making-like-a-star’ routine, no phoniness p in him. He’s down-to-earth, full of real simplicity, utterly kind to everybody, a gentleman and a real professional worker.”

Whew! Well, I had asked the question—and I had sure enough gotten an answer!

And she still had no idea of how the stories about a romance had started?

“None whatsoever!” she exclaimed. “What do you think started them?”

“Maybe,” I suggested meekly, “They might have cropped up when some other interviewer mistook your admiration for Peck as being more personal than professional.” She batted her long, long lashes and said, very seriously, “That could very well be,” and that was the end of that.

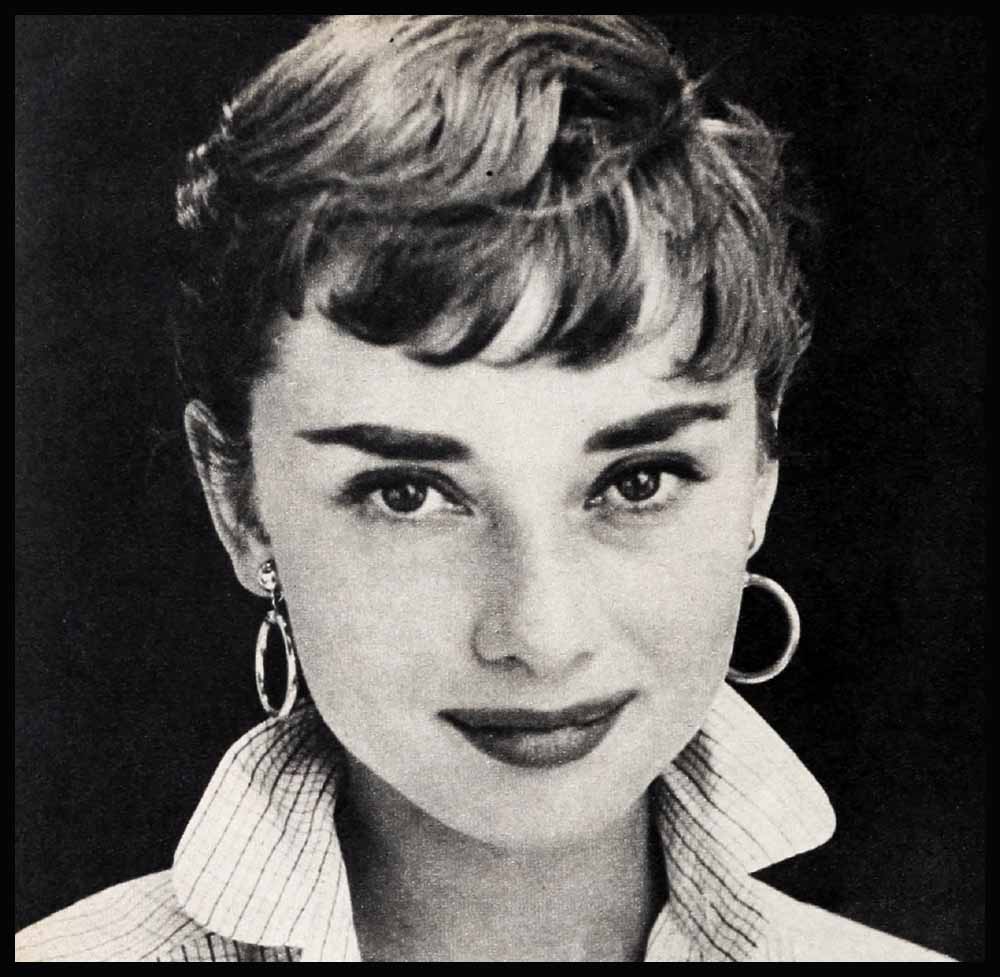

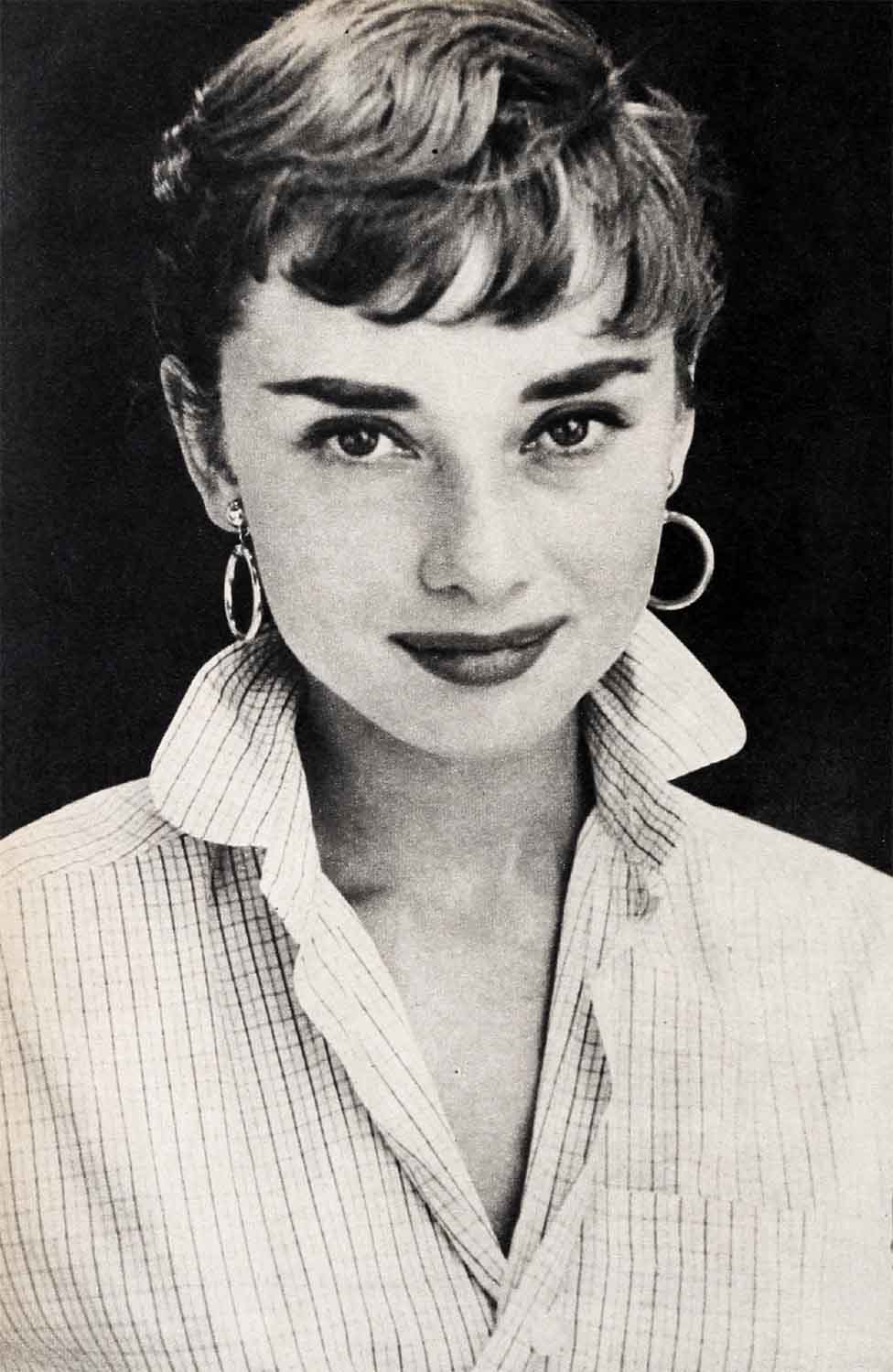

She’s twenty-four years old. Sometimes her eyes are brown and sometimes they’re green. On this particular smoggy morning in Hollywood, she wore only a splash of lipstick and no other make-up, a man’s checked shirt, a full, black skirt and ballet slippers. And she smoked Gold Flake Cigarettes—that’s an English brand—in a long filter cigarette holder. She wore the shirt very interestingly: it wasn’t buttoned at all but the two front shirttails were gathered together, wrapped around her waist Mexican-style and safety-pinned in the rear. “Shirts are so useful,” she explained. “All you do is wash and iron them.”

“You wash and iron them yourself?”

“Myself.”

She also wore Italian loop earrings and her hair was cut very short, even shorter than it was after the actor who played the hairdresser in “Roman Holiday” had finished chopping it off so recklessly!

Although not related to Katharine Hepburn, Audrey has more than her name in common with Katie. Both are angular, lissome and tousle-haired. And both are talented! Audrey is causing the same kind of flurry that Katharine did with her first movie appearance. And she is well on her way to living up to the high-flown predictions that success will smile on her as sunnily as it has smiled on Katie.

Audrey, like Katie, is definite and positive. She doesn’t say one thing and mean something else. She comes right out with what she has on her mind and the devil take the hindmost!

She’s equally strong-minded about which questions she wants to answer and which she doesn’t. She’ll take just so much prying and no more. For instance, I asked what play she is going to do after she finishes her next picture, “Sabrina Fair.” She said, “I don’t want to answer that.” When I asked, “Why?” She said, “Well, I’m superstitious about talking about a part before I get it. But I’ll let you know when and if I do get it!” I respected her for that, although I must say I made a few phone calls after the interview and found out elsewhere that what she meant was Gilbert Miller’s planned Broadway presentation of the London stage hit, “The Confidential Clerk.”

To get back to her physical attributes, her face is the most enchanting part of this sophisticated imp known as Audrey Hepburn. It’s oval and high-cheekboned. It’s angular and yet it’s soft.

Looking at her that morning, curled up on the tangerine sofa in her dressing room, with Photoplay’s photographer, Phil Stern, flashing bulbs at her, I thought, “A very smart cookie . . . with an air of untouchableness about her. A fellow will think twice before he grabs hold of Audrey and tries to kiss her. She’s the kind of girl you want to protect—and yet she gives the impression that she can take care of herself in almost any kind of tight squeeze. She’ll either talk herself out of it or slither out of it! It’s hard to imagine her walking into a room and knocking over a piece of furniture.”

We talked of her career to date, of how the enchanting and talented actress had flashed to stardom on the stage in Broadway’s “Gigi” two years ago, when she was a mere twenty-two. After eight months in New York, she had flown to Italy to do “Roman Holiday.” She spent four months making the picture. Then she flew back to New York, rehearsed for the road tour of “Gigi,” did eight months on the road, including a month in Los Angeles, finished it in San Francisco last May and then went back to England for a two-month siesta.

That’s the story of Audrey’s American career. But she had already won considerable success abroad before making her U. S. debut on Broadway on September 24, 1951. She made her stage debut in the chorus of “High Button Shoes” in London in 1948, and followed that with dancing roles in two more British stage musicals, “Sauce Tartare” and “Sauce Piquante.” The refreshing charm of her antics in these shows resulted in a small part in the British movie, “Laughter in Paradise.” This led to roles in “The Lavender Hill Mob,” with Alec Guinness, in “The Young Wives’ Tale,” in “The Secret People” and “We’re from Monte Carlo.”

It was while she was on location on the French Riviera for “Monte Carlo” that Colette, the famous French novelist, saw her and ended the then feverish search for a “Gigi.” Both Gilbert Miller and Anita Loos had been combing Broadway, Hollywood, London and Paris for a young actress capable of portraying the title role. The aging Colette was sure she saw her Gigi as she watched Audrey do a scene in the lobby of Monte Carlo’s Hotel de Paris.

The part Fate played in bringing Audrey to stage stardom may partially account for her philosophy that it’s silly to worry about the future. She’s sure that if you do your best every day and learn all you can about your profession, big things are bound to come your way. Audrey knows that a star must be a consistently good performer who knows all the angles of her craft. So she continues to work and study, with perfection as her goal.

“If anything bad happens to my career it won’t be the fault of any handling I’ve had,” she says, “because to start with, I have a wonderful seven-picture contract with Paramount, with twelve months off between pictures. That gives me time to do stage work, and I terribly much want to continue on the stage as well as in pictures. My bosses here at Paramount realize I am very sincere about the stage. I’m that way because I feel I wouldn’t last long if I were to do pictures only. I have learned the little I know about acting from my stage work. I think I’ll continue to learn from the stage. Apart from that, I adore the stage and would he very unhappy to leave it altogether.”

I reminded her that only a few months previously, while she was appearing here in Los Angeles in “Gigi” and prior to the release of “Roman Holiday,” Hollywood columnists and reporters had not been too eager to meet her. As a matter of fact, Paramount had had to beg a number of newspaper people to take free tickets to see her in the play. She laughed, “It’s not very nice of you to remind me of that!”

But now she’s back in Hollywood, and in triumph, living in a little two-room apartment on Wilshire Boulevard. “You won’t print my address, will you?” she asked—as though I would! I answered her question with another: “What’s the matter, afraid of Hollywood wolves?” She giggled and said, “Are there such things? Gosh, if there are, I’m no draw—because I just haven’t run across any.”

“What about New York and London wolves?” I wanted to know.

“Look, if you really want to know, I think all men, at least all the men I’ve met, are harmless. Actually, I’ve never yet had to fight off a man!”

I asked her about James Hanson, the thirty-one-year-old British trucking executive who was once her fiance. “We decided this was the wrong time to get married,” she said. “I’ve told you my schedule: a movie here in Hollywood, then back to the stage, then back to Hollywood, and to forth. He would be spending most of his time taking care of his business in England and in Canada. It would be very difficult for us to lead a normal married life. Other people have tried it but it has lever worked. So we decided to call it off. Oh, maybe sometime in the future—but not now, not for a while.”

Her childhood? She’s of Scottish and Dutch parentage. Born in Brussels, she was went to an English boarding school when she was a child. She speaks English, Dutch, French and a smattering of German and Italian. She’s studied ballet, piano, music history and analysis, harmony, dance history and theory. Though she’s had no high-school or college education as we know it, she’s had more than the equivaent from tutors.

Shortly before the outbreak of World War II, Audrey was taken to Arnheim, Holland, by her mother, Ella van Heemstra van Ufford Hepburn, and remained there throughout the war years. It was at ballet school in Arnheim in 1940, when she was eleven, that she was first exposed up the theatre—in a ballet school exercise. Her first public performance was in a show get up to raise funds for the Dutch underground in its fight against the Nazis.

“After the battle of Arnheim, the city was evacuated,” Audrey continues, “and my mother and two half-brothers and myself were moved out into the country, where I danced and taught other youngsters nearby to dance.

“Seven months after the big battle, Holland was liberated for good, but mother and I had an awful time getting out of Holland. Mother is Dutch. My father is Scottish but mother had divorced him when I was six years old and I haven’t seen him since. He lives in Ireland. Before that, mother had been married to a Dutchman, she father of my half-brothers, Alexander and Ian Quarles van Ufford. Anyway, we had an awful fuss with the Dutch and British embassies over my Belgian-Scottish-Dutch background, but finally we got visas and made it over to England.

“Why did we want to go to England? Well, my mother believed in my talent. She had always said, ‘You can do it, Audrey, if you want to badly enough.’

“Don’t misunderstand me about mother. She is anything but the ‘typical stage mother.’ Would you believe it, she has never been to a ballet class or rehearsal of mine! She has never even been on a movie set of mine. She has never been on location with me—excuse me, she was once, but just once, and that was only after I begged her to come and fetch me!”

They went from Holland to London to see Marie Rambert, who runs a ballet school. Their time was limited, because they had only ten dollars, just barely enough to feed them and keep them in a cheap hotel for three days.

Now comes one of the great parts of the saga of Audrey Hepburn: Marie Rambert, recognizing her talent, took her into her own home and housed and fed and schooled her for six months!

“I was always short of money,” Audrey explains, “although I modeled and clerked and did all sorts of little odd jobs outside of school hours. My first class was at 10: 00 A.M. and my last was at 6 P.M., so it was work, work, work, all day and into the night. Then came the chance to audition for ‘High Button Shoes’ and, although I had trained as a classical ballet dancer, with the full classical pulled-back hairdo and my feet turned out even when I went for a stroll down the street, I landed in the chorus of the musical comedy. I had been in London six months when I got it. And that was the beginning. I’m paying Marie back now.”

Then I asked, “Are you planning to return to Europe soon?”

“If that play materializes I will go back to New York and do it on Broadway. If not, I’ll probably go to London and do one there. Or I may even do another picture.”

Audrey is loyal, to her friends and to her family. She told me about Marcel Dalio, a character actor. “I was doing a scene with him in Monte Carlo when Colette saw me for the first time,” she said. “And I’m so thrilled because Marcel is in ‘Sabrina Fair’ with me right here in Hollywood now!”

She told me about her half-brothers, Alexander and Ian, who both live in Indonesia. “I keep sending them books,” said Audrey. “They read an awful lot and Indonesia seems to be very short of books. I am trying to talk Paramount into finding a script about Indonesia so that I can go over and make a movie and visit my brothers there.”

I asked her what she’s going to do with all the money she’s bound to make in her new status as a top Hollywood star. Her answer was quick: “Invest it. I want a lot of security for my mother and myself. And with what’s left over, I’ll buy books.”

Her mother didn’t accompany her to Hollywood, she explained, “because there seemed so little point in bringing her yet. I get up at 6:00 A.M. and spend all day at the studio. She has no friends here and is completely unfamiliar with the town. I’m not too well acquainted either but I hope to be, and when I come back I’ll bring her with me. Then too, I’m no good to anybody when I’m working. I’m like a machine and, because I throw myself into my work, I’m just not worth living with!”

I asked about hobbies. “I like to read, play records, swim and sunbathe,” she says. “I would love to have a real hobby because everybody asks me if I have one. I think I’ll have to develop one, a really interesting one—like shrinking heads! But my trouble is I’m almost always working. I’ve never had both money and time.”

On the question of how it feels to be one of the hottest actresses in Hollywood since Garbo, Audrey says: “Now, really, that’s like asking a man why he beats his wife!” She smiled. “Seriously, I can’t say that I feel any different within myself. This sounds as though I’m not being grateful for all the thrilling things that are happening to me. I am tremendously happy about my success and very grateful when I think about its effect upon all those wonderful people who have helped me: my mother, my ballet and music teachers, the producers, directors and choreographers I have worked with, the people who have put me under contract, the agents who have guided me so wisely, the other actors and actresses who have advised and helped me—the people like Gilbert Miller, William Wyler and Gregory Peck.

“But I don’t mean I am satisfied—that would be fatal! I know that, now that I’ve given what I’m told is a good performance, I’ll be expected to do at least as well, if not better, in my next picture. I want to be ready to meet the challenge.”

The interview was drawing to a close. What more could I ask her about—clothes, perfume?

“Fashions—I love ’em. I can’t wait for the fashion magazines to come out so that I can see what everybody else is wearing. But I design all my own clothes and they’re very simple.

“Perfume? You shouldn’t ask that. It’s a girl’s secret. But I have two, one for daytime, one for evening. No girl should buy her own perfume. It’s the one thing you should get from a beau. But ever since I’ve been able to afford it I’ve bought my own. Dreary, isn’t it?

“Exercise? None, except that I run around a lot. I dance when I have time but I don’t have much time nowadays.

“Books? I read anything, if it’s well-written. But trivial reading? I just don’t have the time.

“Food? Two large cups of coffee for breakfast, one large one for lunch, one after dinner, one just before bed—very pale. In between I guess I eat too, but not much.”

And there you have flat-chested, slim-hipped, altogether un-Marilyn Monroe-ish Audrey Hepburn. But, as Jerry Lewis says—and Jerry works on the same lot with Audrey—“I like it, I like it!”

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1954