How Many Times Can One Heart Break?

“Suffer little children to come unto me, and forbid them not: for of such is the kingdom of God.”

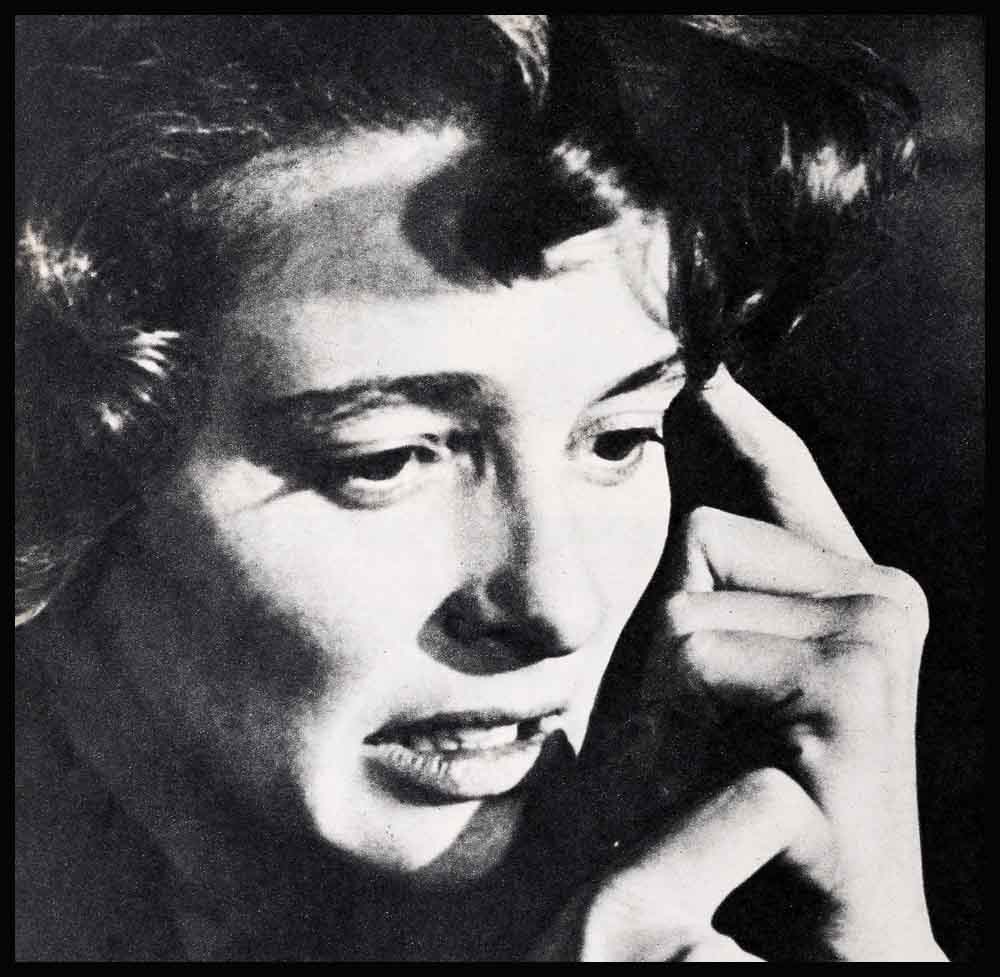

Your name is Patricia Neal . . . movie star, television actress, wife of a successful author. But right now you are none of these things. For right now you are every grieving mother who has ever lost a beloved little child.

You sit in the English country church at little Missenden, Bucking-hamshire, and hear the Reverend S.F.C. Roberts read the funeral service over the tiny dead body of your seven-year-old daughter, Olivia. And it only adds more to your sorrow to recall that this is the very church in which Olivia was baptized, such a few short years ago. Too few, and far too short. . . .

You feel a hand grip yours—a strong, comforting hand. And you look up into the eyes of your husband, Roald Dahl, who sits next to you. Without him, you would never have had the strength you needed today. With his help, you pray that you can face not only today, but the many long, sad days and nights to come. Just as you have somehow faced the tragedy of the past few years. The years since Theo’s tragic accident.

But right now, the present and the re- cent past are too painful to think about. And your mind, seeking some escape, can’t help recalling how different everything was when you were very young—when you were Patsy Louise Neal (how you hated that name!), a tall (far too tall, as you knew only too well) and gawky young girl from Kentucky. You thought of only one thing in those days: that somehow, some way, you just had to become an actress.

And it all seemed so wonderfully easy at first, though of course it was hard work, too. The fortunate meeting with Eugene O’Neill in New York City, where you had come fresh from Northwestern University in search of a break in the theater. After a few months of taking odd jobs to support yourself, you met O’Neill in the Theater Guild offices. And he helped you get a part in summer stock that led to the starring role in “Another Part of the Forest” on Broadway. That was the role that brought theatrical awards showering down on you.

How the folks back home must have gasped when you wrote them that you’d actually sat in a drugstore sipping a malted with America’s number one playwright! But you never dreamed, in those young and golden days in the mid-1940s, that your own life would rival in tragedy the lives of Gene O’Neill’s most star-crossed heroines.

You hit Hollywood in 1948, with a top- paying Warner Brothers contract in your pocket, and gave out an interview that must have come back to haunt you since then: “I’m the original nothing-ever-happens girl,” you told a reporter, apologizing because you didn’t have an exciting life story.

Barely over a year later, you were linked with a married man.

His name was Gary Cooper.

You met Coop when you co-starred with him in “The Fountainhead,” one of your first pictures. Like a knight in armor, Gary—kind, gallant, wonderful Gary—came to your rescue when you needed him most. For something had already gone wrong . . . terribly wrong. All the poise that had helped you sail through your stage roles suddenly left you when you started working in the movies. The stop- and-start, no-rehearsal System made you panic. You couldn’t perform your roles to your satisfaction, and you felt you were botching up your scenes. Not only that—you were once again all too conscious of your height, five feet eight inches, which made you tower over movie leading men. You had even taken to slouching around the Warner lot in low heels, until Jack Warner himself scolded you: “Stand up and be your height!”

And then you met Coop. Who could feel nervous alongside calm, relaxed Coop? What’s more. “She loves doing scenes with Gary Cooper because he is one of the few actors taller than she,” a columnist noted. But it soon became apparent—first to just the two of you, and then to Rocky Cooper, and finally to all of Hollywood—that there was another reason you loved acting with Coop. It was because you loved the man himself. And after you and he had made another picture together, he and Rocky separated.

That was in the spring of 1951—a spring you’ll never forget. For suddenly you found your picture in all the news- papers, with harsh headlines labeling you “the other woman” in the Coopers’ separation. At first you denied that you’d had anything to do with the breakup. In fact, you told PHOTOPLAY, “I’m sure most intelligent people agree with me that no one could break up a happy marriage.” Ironically, Elizabeth Taylor was to use almost those identical words nearly a decade later, in denying that she had broken up the marriage of Debbie Reynolds and Eddie Fisher.

But there the resemblance ended. For Liz is a wilful woman who takes what she likes, no matter how many lives may be affected. But you and Coop both fought against the emotions that swept you both up so suddenly, and even after the separation it was a long time before you were seen in public together. Your strict Southern upbringing made you shudder at the thought of breaking up another woman’s marriage, and it’s obvious that you did think what you said was true—that you can’t break up a really happy marriage.

But the strings that bound Coop to Rocky were too strong to be broken—perhaps to his surprise as well as yours. The separation dragged on through most of 1951, with no sign that he was planning to ask Rocky for his freedom.

The impossibility of your position be- I came painfully clear at, of all places, a party—one of the first you and Coop had attended together. Rocky was there, too, with Peter Lawford, who was then one of Hollywood’s most popular bachelors. Everything seemed to go wrong for you that night. You and Coop came in as quietly as possible, and went directly to the end of the bar. When Rocky came in, laughing and chatting with Peter, you suddenly realized what it meant to be up against a sophisticated woman of the world who was determined to win back her husband. She was superbly gowned, making you all too conscious that your taste in clothing had never been too sure. Her hair was immaculately coiffed, and you realized too late that the flowers in your own hair made you look like an insipid young ingenue.

The worst part, though, came later in the evening, when someone asked you to dance. While you were on the dance floor, you noticed out of the corner of your eye that Coop had gone over to Rocky’s table and was engaged in deep conversation with her.

That was when you realized you’d lost.

“I will not see Coop again,” you told Hedda Hopper in an interview.

“How many times have you been in love, Pat?” she asked you.

“Only once,” you said. And then the pain was too much to bear, and you couldn’t help adding, “Wouldn’t you know it would be just my luck to fail in love with a married man?”

By now Hollywood was all ashes for you. Your romance was over, and your career was slipping badly. Warner Brothers had dropped you, and with your usual candor you admitted to a reporter that the reason was simple: All your pictures had been boxoffice flops. Oh, you were still in demand, and Fox signed you for one or two pictures a year. But your stock was sharply down, and you knew it.

To forget Coop. and to get away from Hollywood with its unhappy memories, you went first to Korea. to entertain the troops, and then to New York, for a Broadway play—“The Children’s Hour.”

And soon after your arrival in New York, the seemingly impossible happened. You met a man who made you forget your heartbreak.

Roald Dahl was a man who nobody could ignore. For one thing—and this was certainly in his favor, as far as you were concerned—he was six feet, six inches tall. A brilliant writer whose satirical and horror pieces glittered in the pages of the New Yorker and other magazines, he loved the theater as you did. But he was no Ivory-Tower dweller. He’d been a Battle of Britain pilot during World War II, and although he was a Scandinavian, England was now his home.

You began dating him steadily. He shared your delight in the glowing reviews for your Broadway performance in “The Children’s Hour,” and you spent long hours going for walks together and talking about books and the theater and about England. (You’d been there for a Command Performance and to make the picture, “The Hasty Heart,” at a time when you felt that you had to get away from Hollywood and Coop—to keep your own heart from being too hasty. If you’d met Roald then, instead of three years later, what a lot of heartbreak might have been spared for three people!)

In July, 1953, you and Roald were married, and on your way to a ten-week honeymoon in Europe. Even your trousseau reflected your new-found happiness. It was all in pink—“a color I feel good in,” you said.

And it was good, your new life. You and Roald set up housekeeping at Great Missenden in Buckinghamshire, in a lovely old Georgian house called Little Whitefields that was only an hour’s drive from London. You found that you loved being a housewife. And now your long walks with Roald were more wonderful than ever, as you explored the green English countryside in springtime and the mist-shrouded villages in autumn. And, before the weather turned too cold, you and Roald went off to New York to spend the winter months in a Manhattan apartment while you saw the shows together and Roald visited editors and wrote.

Your life became complete

Then, a little over a year after your marriage, Olivia was born—and she was a minature of you. She had your intelligent face, and your wide-set eyes and high cheekbones. Two years later, Tessa came along. And on August 2, 1960, your life became complete when you bore Roald a son—Theo, a healthy seven-pound, three-ounce boy who turned out to have smiling, alert eyes and a loud wail.

You continued working off and on—just enough to keep your hand in. And a month after Theo’s birth, you had an offer for a movie that seemed to fit in perfectly with your plans. You were wanted for an important role in “Breakfast at Tiffany’s.” Not the leading role; that belonged to Audrey Hepburn. But it didn’t matter any more. What mattered was that it was a good role—as the society woman who battled Audrey for George Peppard’s affections—and that the movie would be filmed in New York in the autumn and winter. It just harmonized with your trans-Atlantic commuting schedule.

So you and Roald bundled up the children and headed happily for Manhattan—and, it turned out, for tragedy.

For on December 5, 1960, while Theo was being wheeled across a Manhattan intersection by his nurse, a taxicab smashed into his baby carriage and injured him horribly. Little Tessa, who was with him, saw the accident. When you got the news, you rushed to the hospital, and there the doctors told you the frightening truth: Theo had received critical head injuries which might cost his life. For days he hovered between life and death, while you prayed for a miracle to save him.

The miracle came—but it wasn’t enough. As a result of his grave injuries, Theo had to have a tube inserted in his body, leading from his brain to his heart—to drain off excess fluids that had begun to accumulate and threatened his life. But that wasn’t all. Soon after it was inserted, something began to go wrong with the tube. It clogged up, and Theo’s small body had to be opened up again and a new tube sewn in. Again the tube clogged within a short time, and again the surgeons had to operate.

In all, Theo had to have seven dangerous brain operations in the next two years. And all you could do was pray that your child might live, pray that the thin little tube would not clog too suddenly and kill him.

As if your own family’s agony were not enough, another person’s suffering began to touch you. The newspapers told of Gary Cooper’s losing fight with cancer, and across the miles your heart went out to this man, the first man you had ever loved.

But finally, when Coop’s suffering was mercifully over, you could at least thank God that he had died surrounded by the love of his wife and their daughter Maria, with the blessings of the church in whose good graces he had spent his final days. And you knew that your decision eight years earlier, had helped make it possible.

But life goes on somehow. and Theo began holding his own. Finally you dared to leave him long enough to return to America for your most important role in years—as Paul Newman’s co-star in Paramount’s “Hud.” But you had it written into your contract that you were to have two weeks off during the filming, to return to England and your family.

The movie was filmed in Hollywood and in Amarillo, Texas. And as it progressed and people saw the daily rushes, it became obvious to everyone that the movie contained some of your best work. Perhaps it’s true that suffering improves an artist’s ability. Whatever it was, your fellow workers and others praised your performance to the skies. They said you were sure to be nominated for an Academy Award.

But more important than that, the news from England was good. “Theo is beginning to walk,” you told a reporter proudly, “just a few steps at a time; but it is so encouraging to Roald and me. Although our picture isn’t nearly completed, I’m flying back soon to be with my darlings.”

The two weeks with Theo and the rest of your family passed all too quickly, and soon you had to return to Hollywood and finish the picture at the studio.

You were careful not to seek people’s sympathy, but one day at a party a very revealing thing happened to you.

It was a Sunday afternoon swimming pool party at the home of Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward, on Tower Road in Beverly Hills. And although it was a “bring-your-family” party, and you knew the sight of all those other children might remind you painfully of how much you missed your own, you decided to go anyway.

When you got there you saw that most of the children were around the same age as Tessa and Olivia—between five and seven. And you couldn’t help smiling at the sight of them all, as they splashed around the pool and ran over the grass.

But suddenly you saw something that must have made your heart stop. It was a baby, one of the youngest children there—a baby not too different, really from your own Theo. And without stopping to think about it, you hurried over to the child and its mother, a young actress who was holding it adoringly.

“I just love babies!” you exclaimed to the girl, and asked her if you might hold the child. Then, as soon as she gave it to you, you did what might have seemed a strange thing to some people. But any mother would understand, as this one did.

You took the baby into another room, and settled down in a comfortable chair. And then you just sat there and looked at the baby, and held it and held it. You just sat there, for almost an hour, holding it, smiling at it, lost in a world of your own. At last, you let the mother have her child again, and once more you were alone.

Finally, as England’s short summer turned to autumn, the picture was over and you were back with the children and Roald. The family was complete again.

But then, in late November, there came the worst sorrow of all—a sorrow that must have made you wonder, “How many times can one heart break?”

Olivia, who had been a healthy, active seven-year-old, fell suddenly ill. At first it seemed to be only a case of measles. But as you watched helplessly, it turned into something much worse: The dreaded encephalitis—a most often fatal disease that causes inflammation of the brain. The doctors did their best, but it was useless. Olivia died just a few days before Thanks-giving.

Now her funeral is over, and with Roald at your side you accompany the small casket to the cemetery, where it is lowered into the ground. Gently the minister scatters earth over it: “We commit the body of this child to the ground . . . give her peace, both now and evermore.” Finally it is time to go home with Roald—home to, Theo and Tessa, who will need you more than ever now. And as ( you walk away from the freshly-made grave, there is nothing to say, really, and nothing of do. Nothing—except to wait for time’s inevitable healing to begin, and to live for the future, and for those who remain.

—JAMES GREGORY

Pat’s new film is Paramount’s “Hud.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1963