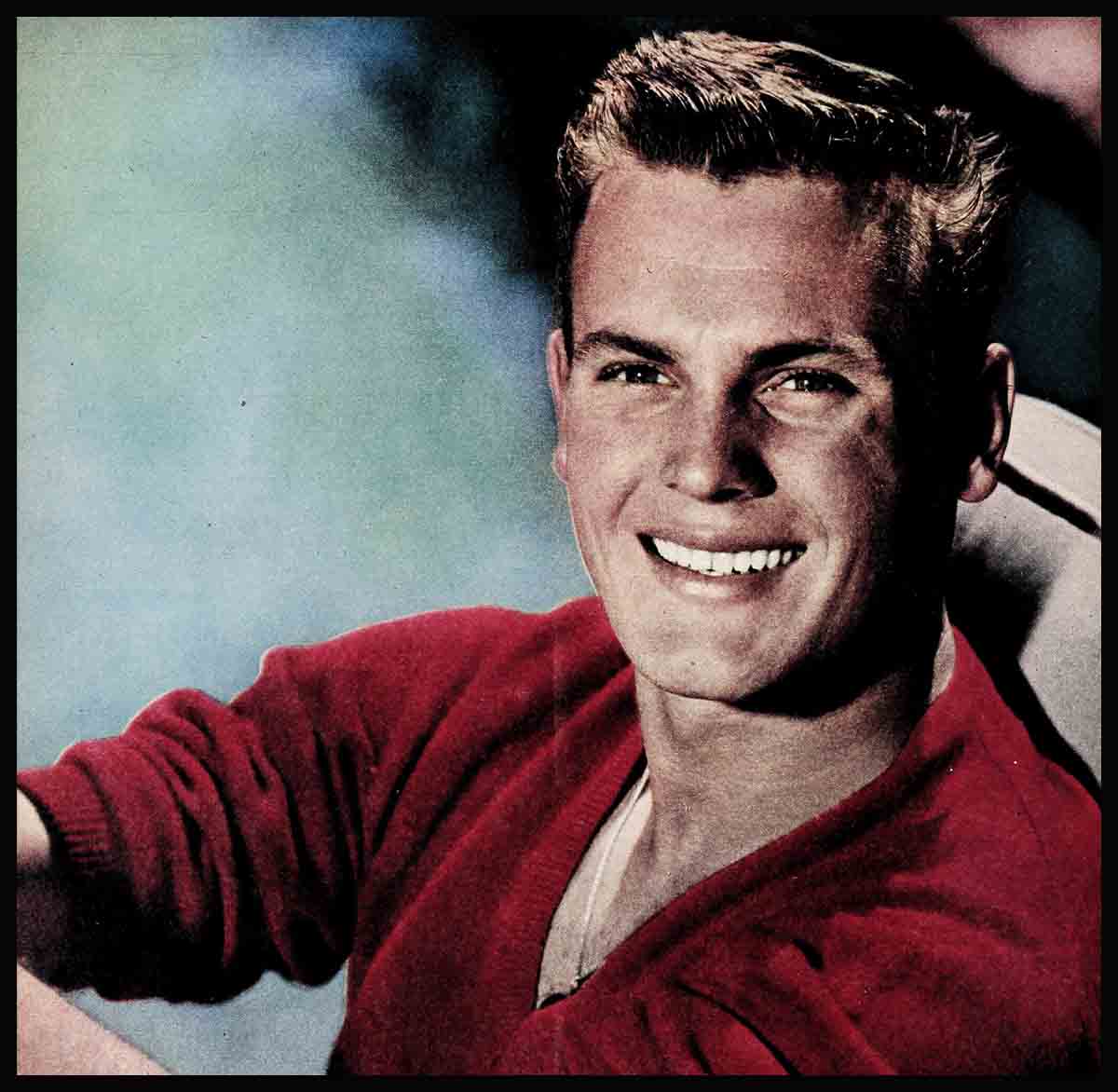

I’m In Love With A Wonderful Mom—Tab Hunter

It’s funny how you can remember little things from ’way back when you were just a kid. I don’t think I’ll ever forget one autumn morning that my brother Walt and I waited for mother to come home from a trip. It was one of those cold San Francisco autumn mornings; the kind of morning you hate to get out of bed. But this day both Walt and I were up and dressed early. I remember I had on my best pair of pants. They were brown corduroy and every time I crossed the room to watch out the window for Mom, they swished and made a funny sound. I also had on a tie. Walt and I didn’t usually wear ties, but today was important. We hadn’t seen Mom for almost a month. She was working on a steamship line as a physiotherapist and was away a great deal. Not seeing Mom each day was hard on Walt and me—there was an emptiness, a kind of aloneness. We didn’t talk about it much, Walt and I, but it was there. Like the feeling I had when the teacher told me, “Take this slip home and have your mother sign ” But Mom wasn’t home. Or like the time Walt tore his pants, but that didn’t much matter because Mom wasn’t home to reprimand him.

I think maybe not having Mom, always, is one of the reasons I feel so close to her today. There’s a lot of talk these days about “mom” and “Momism” and the harm mothers do. I don’t think this is fair. I’m close to my mother—in fact, there are very few important things I believe in or hope for that aren’t in some way wrapped up in her. And I’m proud of it. I wouldn’t have it any other way. But so many people think that because you’re close to your mother, you’re tied to her apron strings. Well, if I am, they’re pretty long strings ’cause ever since I was a kid, I’ve always had free rein. I came and went, when and where I pleased. It’s the same now.

To understand this, you’ve got to know Mom. My Mom’s a regular Joe! She’s an amazing woman—a real woman. She’s had to go it alone almost all of her life; she never had any love, yet she never gave out anything but love. She’s had the kind of courage that’s a constant inspiration to any boy—to any man, in fact.

Mother was born in Hamburg, Germany, one of a family of four children. She had a sister, two brothers; one brother is Mom’s twin. There was little family spirit; little warmth, only a rigid firmness. Because of this, Mom brought my brother Walt and me up to be very close. As a child, Mother missed the warmth and affection of a close family life, she missed the fun of Christmas holidays, the pleasant surprise of a birthday party, even the warmth of a goodnight kiss and a tucking in at bedtime. Because of this, Mom made extra sure we had these. Even as a teenager, there was no fun for her. Laws in her house were made not to be broken. On her first date, Mom remembers—and she has reason to—she arrived home five minutes after the curfew set by her father. The door was locked. That night Mom had to sleep outside, in the snow, and the next morning she was refused breakfast and was rationed out a few pieces of bread crusts. Sounds like a Grimm fairy tale, doesn’t it? But it’s a fact. When Mother was sixteen, her family brought her to this country and pushed her out to work, doing housework and other odd jobs, real tough work.

To get away from it all, Mom married soon after. But it was not a happy marriage. The only brightness, she says, was Walt and me. I was born a year after my brother in New York’s Bellevue Hospital. While there, my father came to visit my mother once and threw a five-cent candy bar on the bed. This was the gift he brought her. Mother has often told me, making it sound funny, about the day she was bringing me home from the hospital. All the other mothers were proudly showing off their babies, all dressed up in pretty new baby finery, and Mother could have cried she felt so bad—all she had for me was a little shirt and blanket.

I don’t remember much about my father. The only lasting impression I have of him is one day, when I was very young, he was striking my mother and I tried to stop him by grabbing at him, but I couldn’t hold him back.

Mom doesn’t talk much about those early years in New York. She just keeps everything on an upper level, always has—and it’s beautiful and gallant of her. But she’s told us, laughing, how she used to wash our diapers in a tub by the light of a candle stuck on the edge of the tub. I can half remember watching her scrubbing away and saying to us, over her shoulder, “Soap and water are cheap, don’t ever forget that.”

We didn’t ever forget it—even as we grew older. What Mom meant was, “Cleanliness is next to godliness,” and she didn’t mean just bodily cleanliness, either. My going out for sports, first horses, later on skating, stems, in some way I can’t quite explain, from this soap-and-water maxim of Mom. Maybe what I mean is that my love of sports, which are clean things, comes from the love of clean things Mom instilled in us.

Another thing I clearly remember is being taken for baptism by a woman who used to take care of us while Mom was out working. Knowing that her unfortunate marriage wasn’t going to last, Mom had us baptized in the Catholic Church with the hope (one of them) that when the time came we would take time and thought and prayer to our marriages which, as a Catholic, would have to last. My brother’s is lasting—and happily. Mom is hoping the same for me. Before I marry I’ll take time and thought and prayer to it.

Fortune took its first turn in our favor when Grandfather Gilien, my mother’s father, who was a Captain on the Matson Line, and who softened as the years went by, booked passage to San Francisco for us, got us an apartment and paid two months’ rent in advance. In San Francisco, Mom started training for the nursing and physiotherapy work she’s been doing ever since.

Things were still pretty rugged, though, for a woman alone with two boys to raise. Sometimes there weren’t any jobs; sometimes the jobs there were didn’t pay enough to make ends meet. Mom had a physical handicap to overcome, too. When she had her tonsils out, they’d accidentally cut the vocal chord so that for years she stuttered badly. She had a grief, too. In San Francisco, Mom married a man named Harry Koster. We were all very devoted to him. Harry was killed in the second World War.

Everything that can mow a person down happened to Mom. But she never lost her courage.

“Things aren’t too good now,” she used to say, “but they’ll be better.” That’s what she always said. It stayed with me, too. A prop. A challenge. I couldn’t ever beef or feel sorry for myself—about anything! No, ma’am. Whenever things looked dark brown, like the two years I put in in Hollywood before I got my break in “Island of Desire,” or when I did “Return to Treasure Island,” in which I, like the picture, was a dud, I’d say to myself, tongue in cheek but from the heart, “Things aren’t too good now, but they’ll be better.”

“Don’t ever regret anything that happens to you,” is another of Mom’s maxims. “Everything that happens to you is an experience worth having, if you learn from it. You can only learn by experience.”

You sure do. You learn by association with a woman like Mom, too. She’s never been bitter. With a woman like this, you can’t help learning. They’re great things, mothers.

After we’d been in San Francisco awhile Mom got her job as a trained nurse and physiotherapist on the Matson Line, making the run between San Francisco and Honolulu. This enabled her, between runs, to be with us. She’d be in, then out again. We moved around a lot, were left in the care of friends or stayed in an apartment with Mrs. Kelson, the woman Mom hired to look after us. Although we never had, properly speaking, a real home, Mom managed somehow to give us a feeling of home. She, who had so little, gave us a most wonderful childhood. There were never elaborate presents or anything like that, but we knew that everything Mom did for us came from the heart. We always had the warm feeling, the kind of security that comes from a love you know can never fail—it was a priceless gift that money couldn’t have bought. Life with Mom taught me that money can’t buy happiness.

Another thing, Mom always kept us immaculate. We always wore short pants; I remember our shirts washed and ironed, our shoes shined, all neat and clean. Pride of person, the sense of human dignity, of which she has so much, is one of Mom’s many legacies to me. For although between pictures I may, and usually do, hack around in jeans and T-shirts, they smell, believe me, of that soap and water Mom holds so cheap—and so dear.

Mom was equally particular about the things we said and did and the friends we made. Whenever she had money and saw an opportunity to move us to a better neighborhood, she always did. She couldn’t send us to the best private schools, but she did the best she could—and always expected us to do the same, too.

“What you learn,” she said to us, over and over again, “no one can take from you, so study hard.”

When, later on in Los Angeles, Mom got a very good job with the Matson Line, she sent us to St. John’s Military Academy where we boarded for two and a half years, which was wonderful training for us. Mom did everything for us, which meant she denied herself. To be truthful I don’t remember her ever having more than one dress—up to a couple of years ago, that is. For Christmas last year I gave her a tweed suit from England, a camel’s hair coat, charcoal gray skirt from Switzerland, four cashmere sweaters—white, deep yellow, wood violet and charcoal gray—some pearls and pearl earrings in a jewel box, all gold, all lined in maroon velvet, with a butterfly pressed on the lid which plays, as you open it, a Schubert sonata. And boy, what a kick I got from giving them.

I’ve also given Mom a car (this was after she took over my old apartment and I moved into my new one). This was my first real present to her and I made a production out of it! I had it driven around to her street in the dead of night. Next morning, early, I phoned her.

“Look out the window” I said. “What do you see?”

“I see a light-colored car,” Mom said, “a ’fifty-one or ’fifty-two Chevvy, looks like.

“I’ll be right over,” I told her, “with the keys.” Well, she flipped. This was the first car that was ever hers, outright, the first one she didn’t have to worry about payments. Mom’s like a kid when you give her things, she twinkles all over. I tell her she’s like a Cocker puppy; she’s a kick all right!

This getting-a-place-of-my-own deal throws another beam of light on Mom and the way she is. You hear so much about how mothers resent it, get all crushed, when their kids want to have places of their own. Not that girl. When I said to her, couple of years ago, “Gee, Mom, I’d like to get an apartment of my own someday,” all she said was, “I’ll help you find one after work—only thing, get a cheery place!”

First time she came to see my new apartment, “Bless this house,” she said as she walked in; then, looking around her, “It looks like you.” And as she was leaving, “Just one thing,” she said, “your wool socks—I’ll do them for you. You can pay me if you want, but don’t send them to the laundry, they’ll come out like boards!”

The fact that Mom’s only worry was my wool socks didn’t surprise me. So many parents worry about their children, but in spite of her single-hearted devotion to us, Mom never has. “Thoughts are things” she always says. “If you hold the thought that your son will meet with an accident or is going with fast women, you make it so.”

There’s a lot of salt and spice as well as the sweetness of self-sacrifice in Mom. She’s never syrupy. She packs a punch. I remember the first time I wanted to smoke (I was twelve). “I want you,” Mom said, advancing upon me, lighted cigarette in hand, “to take a deep, deep puff.” I hadn’t any choice and knew it. I took the deep deep puff. I went “Agghhh!” I turned green, red and blue. Id had it!

She’s the first one to tell you when you’re good and when you’re bad. When I first went into the movies, “Whatever you do,” Mom said, “just every day thank God and don’t you ever forget it.” I knew what she meant—that the real credit belonged to Someone bigger than she or me! When I got my big break in “Island of Desire,” “You’re going to go far,” she said, “you can’t help it. I’ve always known it.”

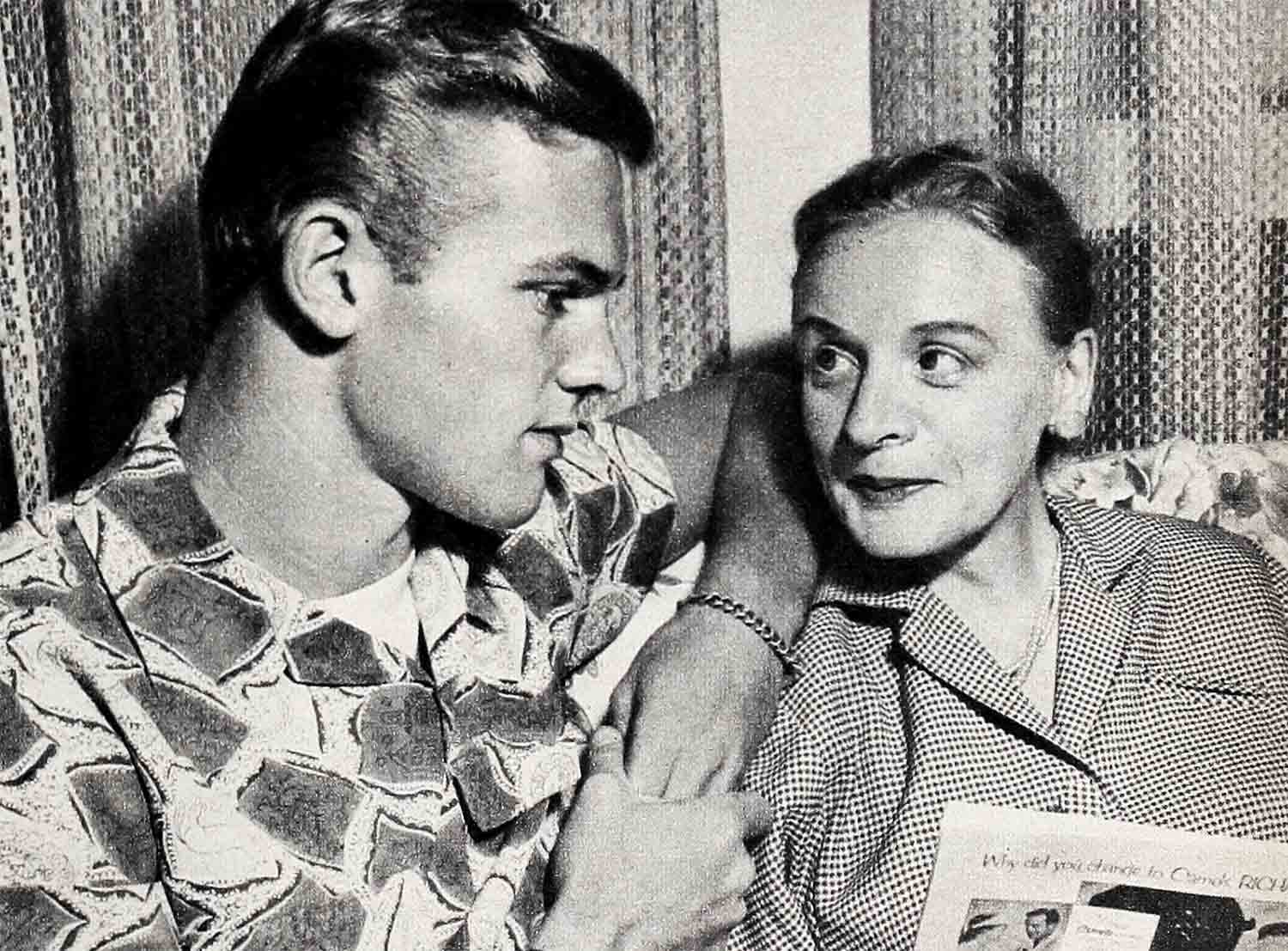

She’d paper the wall with my pictures, I bet, if she dared to risk the laughs she’d get. She’s always telling me, “I do wish you’d let me know when articles about you come out in the magazines. I get a kick out of seeing them.” But when I made “Return to Treasure Island,” “Did I ever laugh!” she said, looking me over with an appraising eye, “Boy, were you—” she stopped for a word—“lousy, in that! I was really in the aisles!” “Track of the Cat” she liked. “The man who did that must have a great soul.” When she met director Bill Wellman, the “man who did it,” “This man,” Mom said, “has a wonderful heart. Earthy.” As of this moment, she hasn’t seen “Battle Cry.” When she does, she’s going to flip. I can feel it coming. It will be her picture.

Mom’s given us values, too. A very important one is the value of friendship. “If you can make five friends in life . . .” she’s always said, and we’ve known that what she means is, that you have to give of yourself to friendship, give a lot, so you can’t spread it out too thin. The number five about does it, too, as far as I’m concerned—my brother, whom I’m very close to, is my friend. Dick Clayton, my manager. Ron and Patti Robertson, childhood friends from the days when we were kids together. Lori Nelson, a real good friend. (Friend? Hey, let’s warm it up a little!) I’m nuts about Lori. To me she is wonderful, a real dream girl. A Sweetheart. Lori’s the type you could bring home and say, “Mom, this is The Girl”—and Mom would just flip! (How about it, Mom, what say?)

Another thing Mom often says and deeply believes is: “Good things happen to good people”—the woman’s a poet!

“It’s the principle of the thing,” is another of her daily reminders. “Principles are so important,” she says with such earnestness her eyes are wide blue saucers. “Integrity is important.”

I kid Mom about these daily reminders of hers.

“All mothers,” I tell her, “have the same script writer. ‘It’s the principle of the thing,’ ‘You’ll be the death of me yet,’ are lines they all use. ‘Well, it’s for your own good’—that’s a line they always use. I’ve heard Lori’s mother use it on her. I’ve heard Mrs. Robertson pull it on Patti and Ron. I’ve heard you—really, Mom,” I say, pulling her leg, “the dialogue runs the same!”

So it does. But believe me, if you hear it often enough, some of it sticks!

I keep kidding her. “Now, why don’t you get married?” I’ll tease just for the kick of hearing her say, “Now who, at my age, would want to marry me?” Mom’s name is Gertrude and she hates it, so I always call her “Gorgeous Gertie” and she hates that worse! I kid her by reversing whatever she says to me. Like whenever I have two drinks, Mom will say, “Don’t you think you’ve had enough? You know,” she always adds, in a stage whisper, “alcohol numbs the brain.” She’s had maybe one cocktail but, “Don’t you think,” I come back at her, “that you’ve had enough? You better stop,” I whisper in her ear, “before your brain’s numbed!”

I’ve always kidded Mom—she’s a great one to kid.

I’ve always been able to talk with her, able to lay things right on the table and discuss them. “Honey,” I’ll say to her “I feel blue today” and after talking to her for five minutes, I feel picked up. A woman like this, with whom you can just sit down and tell anything is not only a mother but a friend. This is a good relationship. What I think is that not enough parents teach their kids the right things. They give their kids things, the kind that don’t last, but not enough of the things like daily reminders and kidding together and companionship, that do. Maybe this is what the writing fellows mean when they let loose their blasts at mothers. I wouldn’t know.

I have, and I sure thank God for it, no way of knowing because the things Mom has given, and still gives me, are the things that last, the right things. The first-rate things. She knows just instinctively, what is first-rate, what’s right. Never anything (or anyone) cheap or vulgar or second-rate for her. She loves good books, good paintings, sports (has always loved my skating), good music. She’s crazy about classical music. Always listens to the Met broadcasts on Saturdays. Her one big ambition is to go to the Met and I got news for you, Mom, you’re going to get there and pretty soon, too!

A movie fan, too—she loves Fred MacMurray, mad for Gregory Peck, a Boyer fan from ’way back!

She’s got good taste in clothes, too, very smart, very plain and simple taste. She always wears gloves on the street, never goes without a hat. She’s a lady, a real lady.

A real and a great lady and good woman and good mother. I could go on but the space in Photoplay isn’t limitless. So I’ll just sign off by saying, “Here’s to you, Mom—and thanks for everything!”

THE END

—BY TAB HUNTER

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MAY 1955