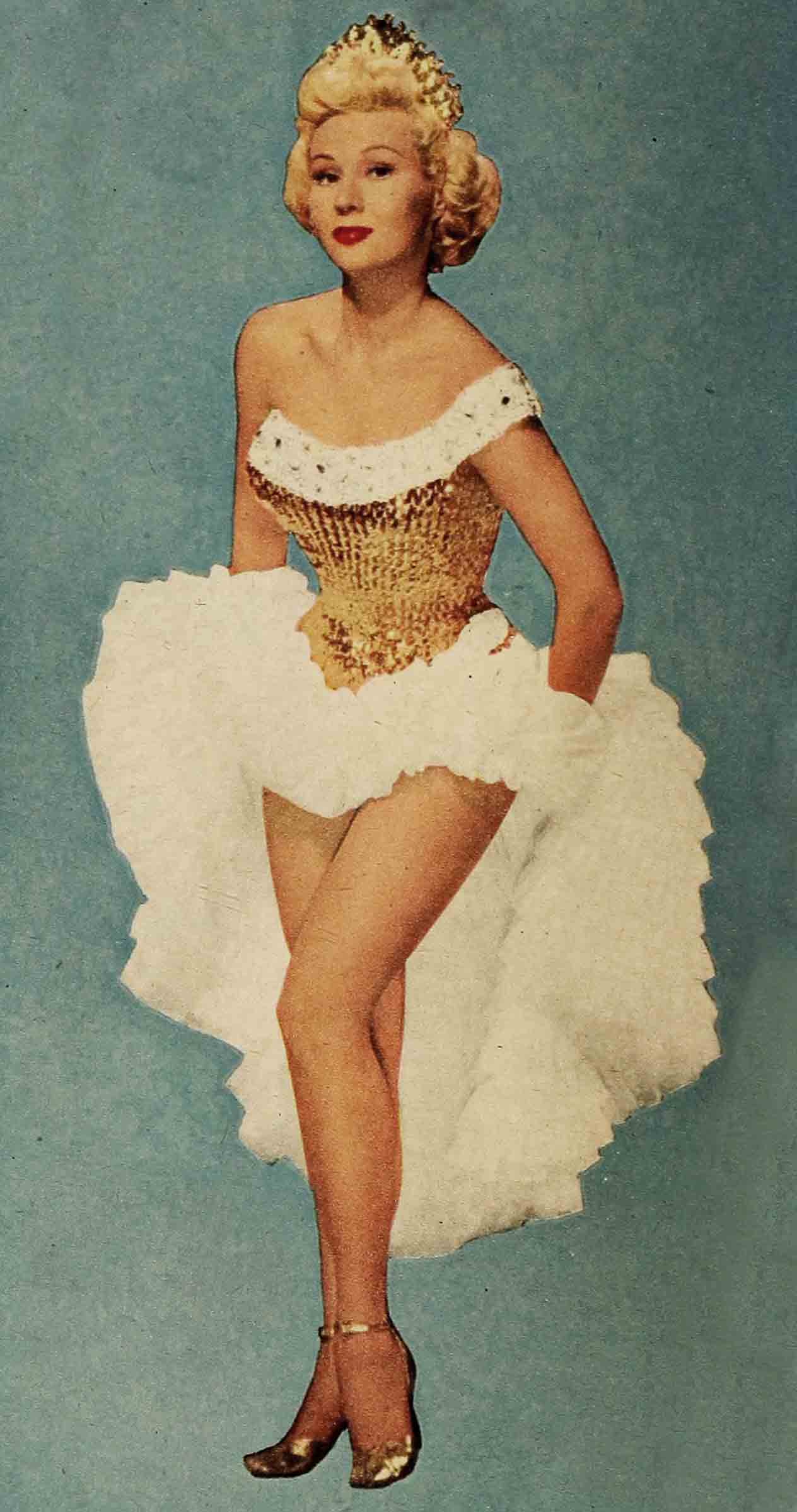

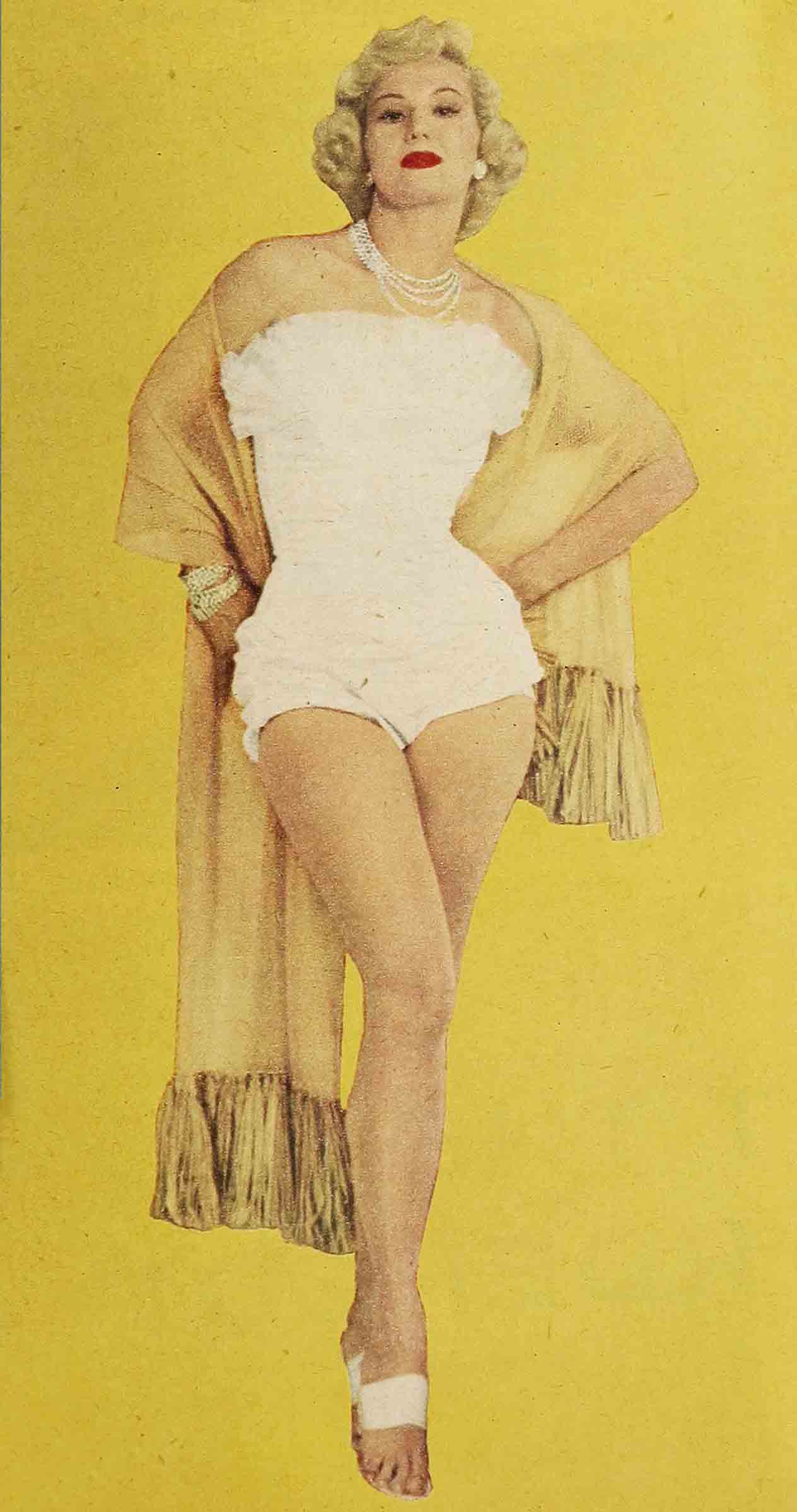

Somebody Has To Stay Home—Michael O’Shea & Virginia Mayo

Most everybody in Hollywood knows that the Green Room of Warner Brothers studio in Burbank, California is the classier of the lot’s two public commissaries, and second in caste dignity only to the private dining room of Jack L. (Himself) Warner, who according to legend has not eaten in the Green Room since the day a character actor; no longer connected with motion pictures in any form, slapped him on the back and told him to run out and get him a beer. But the Green Room is not a good place to conduct an interview for one very sound reason: it suffers from trick acoustics.

Thus, while it was perfectly possible one day recently to hear the lunch conversation of Howard Keel and Jane Powell, emigrants from Metro sitting two tables away, it was extremely difficult to get a word Virginia Mayo was saying, not to mention Michael O’Shea, who of course is Miss Mayo’s husband, not to: mention a lady publicist, who was along to make sure that every syllable was spelled right. And all were at the same table with the person who was trying to hear them.

The problem was roughly this:

Mr. O’Shea had been a pretty hot shot around Hollywood when he married Miss Mayo, who had been as cool a shot as anyone can expect to be when employed mainly to stand behind Danny Kaye while he makes faces. But then, as Miss Mayo went up, Mr. O’Shea went, to put it rather brutally, down, and how had the O’Sheas coped with a situation that would seem to have contained the seeds of strain? The question obviously was a delicate one and would not have been presented at all were it not for MODERN SCREEN’s working premise that O’Shea was now in ascendancy again. Regrettably, it is necessary now to scratch one working premise.

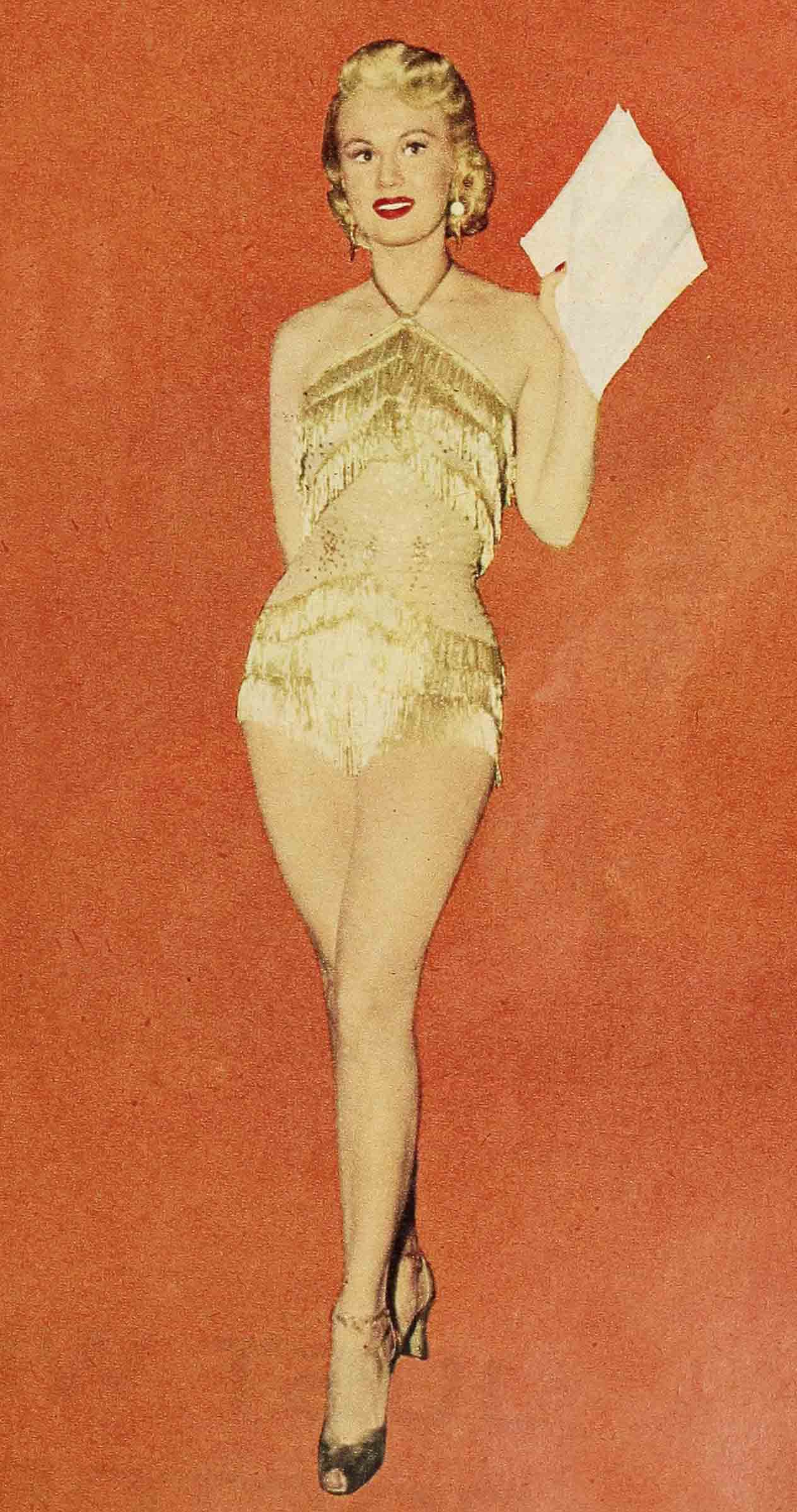

By and by, while O’Shea peered moodily over a fruit salad deal that looked like a funeral wreath and Miss Mayo clutched a light coat across her working clothes—a black lace slip, for the picture The Marines Had A Word For It, the interviewer went about his task in real subtle fashion.

“You’re re-making A Star Is Born out here, aren’t you?” he said. “Judy Garland?”

“What?” said Miss Mayo.

“A Star Is Born! You know, that picture they made back in—” A Star Is Born won the Academy Award in 1936. It concerned a male star who married an unknown, lived to see his stardom melt and sputter out as hers became a spectacular reality, and resolved his problem in the end by walking out into the Pacific Ocean, into the sunset, with no notion he could reach Hawaii or even Catalina.

O’Shea heard the question. “Oh, sure,” he said. “That wouldn’t be for me though. I can’t swim. Brother, the guy in that picture was really a ham. Not Freddie March but the part he played.”

“Norman Main.”

“What?” said O’Shea.

“Let’s get out of here,” said Miss Mayo. “Let’s talk in my dressing room. Goodness.”

Miss Mayo’s Pontiac convertible was parked right outside where anyone could admire it, or trip over it, or let the air out of the tires. O’Shea said he’d get his car and meet us over there. His was a Jaguar sedan, very lush. The dressing room was one of those set jobs, a mobile with enough room for four people and an ashtray. En route, the approach was spelled

out to Miss Mayo. “We thought now that Mike’s up there again, you wouldn’t mind talking about it.”

“Well—he’s not,” said Miss Mayo. “But—oh, I don’t know.”

“I know,” said O’Shea. in the dressing room, “I know what you want.” He turned to his wife. “They want a story, let’s give ’em a story. It’s all right.”

“If you’d rather—” began the interviewer.

“No, no, it’s all right. You think I worry about What They Say. If I worried about What They Say, I’d be six feet under right now. That goes for anyone who stays around Hollywood long enough. After a while, you get so you tune yourself out like a hearing aid or you give up. It’s one or the other. Anyway, what can they say? This one here—” (Miss Mayo) “—and I don’t worry, so why should anyone else? It’s not that I can’t get work. I can get work. I could go to New York. I could’ve had Guys And Dolls. Or others, the titles don’t matter. I just finished reading a play that was offered to me. I don’t like it. I won’t do it. It’s another of those kid-the-government things. I happen to think now’s a good time not to kid the government. But I can get work. Only look at it this way: somebody’s got to stay home. I’ve thought about an article like this and that’s what I’d call it. ‘Somebody’s Got To Stay Home.’ ”

“Europe,” said Miss Mayo.

“That’s right, Europe,” said O’Shea. “Virginia had to go to Europe to make a picture. If I’d been working in New York, do you think I could have gone with her? And do you think I want my wife—?”

“A girl can’t just go to Europe by herself,” said Miss Mayo. “Mike gives up so many things to be with me.”

“Say I’d taken Guys And Dolls,” said O’Shea. “A year, two years, three—away from my wife except for when she could get East, and that wouldn’t have been often because this one, she works like a gopher. Is a marriage supposed to stand up under that stuff? I wouldn’t like to bet you.

“Now I’m a useful human being, I’m part of the team. Virginia goes to the studio, I do what has to be done around the house and grounds. I’m the cheapest handy man in the San Fernando Valley, no salary. Don’t think I can’t do it either. There’s a wiring job got to be done right now, a big one. You think we’re hiring a crew for it? Nope, I’m doing it. Like today, I come in here for this talk and I get out of the denims and put on this—this flashy set of threads—” (O’Shea was wearing a grave, single-breasted oxford gray suit) “—and as soon as we’re through, I’ll drive back and be in the denims and working again. I mend fences, fix leaks, repair roofs, you name it and I can do it. All for the price of none. And do what I can for a happy marriage. Is that bad? Am I that Freddie March character, has to drown himself to prove whatever he was trying to prove? Am I such a gutless chunk of ego I can’t face a world because my wife happens to be doing better than I am? Am I supposed to be ashamed? I’m not. I’m proud. I’m proud of this one here and of our marriage and that I can hammer a nail straight and don’t mind doing it.”

“And I’m proud of him,” said Mrs. O’Shea, very much as though she meant it.

“But don’t make me sound as if I were through,” added O’Shea, “professionally speaking. I’m not through. You know, something? I still make more than Virginia makes—when I work, I mean.” The figure $2500 a week came up somewhere in the conversation. “A producer will call me about a part. He’ll say, “Look, Mike, I know it’s just a bit but the bit needs you. Will you do it as a favor to me?” So the bit needs me, so I need the bit. So I do it.

“Listen. I’ve been in show business for—well, for plenty. Why should I kid anyone, you or the readers or anyone. You’re up, you’re down. Maybe six or eight years from now, Virginia’ll be through and then I’ll step in again. The poor man’s Bogart. I had my chance. I want Virginia to have hers while she can get it,” says Mr. O’Shea.

“He does,’ said Miss Mayo. “A woman’s career isn’t as long, you know. Mike wants all this for me. He never interferes, just helps.”

“Anyway, who’s kidding who?” said O’Shea. “I got in this business on a raincheck. Now the field’s dry again and I’m out. So what? Those were the war years. I was almost over-age when the draft began and I never did get in. So they were desperate for actors. Faces like mine even. You could walk, you could talk, you could breathe? You were hired. Lock the doors and don’t let him out! We were luckier then than we had any right to be. Now the first-string lineup’s back and we’re where we started out. Ordinary system of compensation. Who’s going to cry about it?

“Now this one works and works and brings home the larger share of the bacon. Maybe some people wonder how I feel about that. I feel this way: it doesn’t matter as long as there’s bacon. I learned that the hard way. The gossips don’t matter, the columns, the whispers, the critics, the notices. What matters is that the sprinklers work and the dogs get fed and the house has a roof and maybe there’s some left over. That’s what matters. A lot of that bacon’s mine, you know. I make two pictures a year for Fox. I didn’t marry this one here for her money. She was making—what was it, honey, a fast 80 bucks a week? A fast 80. I was doing pretty well then. If you can’t have it both ways, you settle for one.

Somewhere in the dim recesses of the interviewer’s mind was the recollection that this was to be a sounding out of Miss Mayo. It didn’t seem to matter now. She sat and was decorative and sympathetic and amused by her husband’s able rhetoric, and in effect turning stage center over to him without a struggle. This was partly because Miss Mayo is in truth the shy, withdrawn member of the family, O’Shea the fizzing extrovert with a remarkable stock of Irish gaiety and courage. But it was also, according to later information, because it was the way Miss Mayo wanted it and always wants it. Vis-a-vis her husband, Miss Mayo regards herself as strictly second billing.

It is not surprising. O’Shea is as arresting a personality away from the screen as Miss Mayo is on it—mercurial, gesturing, restless, full of the articulate patois of show business. Miss Mayo evidently has subordinated her social facade to his, and with the utmost willingness. It would not be fair to say that she is his straight woman, but it is her tendency to cue him and then sit back.

“But he draws her out amazingly too,” a close friend of both has said. “Virginia is shy, there’s no getting around it. But when she’s with Mike, a kind of glow comes over her. You can almost see it. She talks more easily and sometimes becomes almost as animated as he—and Mike’s one of our more animated citizens.”

O’Shea is wearing his hair en brosse these days, or what Hollywood calls a Butch. Under it, his face is almost ageless, although he must have slipped past 40. Now the conversation got around to a topic that must have been painful to both of them, and emphatically so to O’Shea. Not long ago the first Mrs. O’Shea instituted renewed alimony proceedings with the argument that O’Shea could pay her more than me did because of the O’Sheas’ joint income; magnified by Miss Mayo’s salary.

O’Shea’s voice lost none of its crispness but he looked at the floor for the first time. “My business manager,” he said, “knows what he has to do: pay her exactly half of whatever I make. That’s gross, not net. Off the top. She’s a nice person. She really is. But this thing—well, I’ll tell you this anyway. If she’d won, I know of a lot of stars would have been heading for the hills the next day. It was that kind of a case.

“You see, my first marriage, broke up 16 years ago, and I hadn’t got a divorce till I met Virginia because why did I want a divorce? I wasn’t going to marry again, not me Id had it. As I say, she was a nice person and still is, but it just didn’t—you know. I was show business, and she wanted me to get over to the rubber works and stand in line. Who’s going to blame her? Eating three times a day, that’s a habit that’s hard to break. But the rubber works and I were incompatible. So. It lasted a couple of years. Then I was in show business again, way down on the level that looks up to burlesque as the end of the rainbow. Any restaurant between here and Philly, I don’t care where, any restaurant that has out a sign ‘Our Specialty, Spaghetti and Meatballs,’ I’ve sung in that restaurant. Save ‘Mother Machree’ for the late show, when they’re maudlin, and they throw quarters instead of dimes. ‘Shanty in Old Shanty Town,’ that was me. But there were no alimony problems. Not like this one.”

“Oregon doesn’t recognize alimony,” said Miss Mayo.

“That state is going to get populous,” said O’Shea. “Anyway, she started out by trying to get—” He mentioned a famous Hollywood attorney. “So we went to him, too, went to him with all our books, every last figure, and it ended up, he wouldn’t take her case. But another lawyer did.”

“I had to make a deposition in his office,” said Miss Mayo. “The other lawyer, I mean. And the doors were open and reporters and photographers everywhere. It was like a circus. Finally I just had to refuse pointblank to say or do anything until we had privacy.”

“Well,” said O’Shea. “It’s over.”

An inevitable query arose. Did not O’Shea find the days very long on occasion, too long, with the hours crawling by on hands and knees?

“Some days,” said O’Shea, “not usually. The fence, the wiring, the TV goes haywire, I work with the horses, the day is through before I am. But some days it’s not too good. I walk to the window and I look east and there is New York over there, where I could be working steadily. So I walk to the other side of the room and west is the ocean, and maybe I should be on the beach, but I know I shouldn’t. And here I am all alone—hum ‘Mother Machree,’ will you, honey?—the hell and gone away from anywhere, and for a couple of minutes I feel sorry for myself. Then I think that in New York it’s snowing or raining or blowing and the show I’m in runs a fast week. I picture the beach and remember I can’t swim. So that’s that.

I mentioned the horses. I like horses and roping and all that rodeo stuff, but I got to taper it off now. You know why? I bounce higher now than I used to and the ground’s getting harder. I think it’s going to outlast me.

“But let’s keep pathos out of this thing. Do me a favor and keep pathos out of it. Maybe you wanted something about the brave little woman’s unflagging courage and radiance pulling us through or how her inspiration brought me back to the top; or what a hot rock trouper I am myself. Just forget all that. We’re doing fine. Just remember—somebody’s got to stay home.

“No nostalgia either. They talk to me about the smell of grease-paint, as though they expected me to cry. ‘Shanty in Old Shanty Town’ goes with that one. Nuts. The smell of grease-paint makes me want to gag. I’ll settle for hay.”

O’Shea looked at his wife and remarked that she was beautiful, an understatement.

“And it’s not too tough having this one here come home to you,” he said.

“It’s not too tough going home to that,” said Miss Mayo.

“And it’s not as though—”

“—we weren’t still in business together,” said Miss Mayo. “Mike and I collaborate all the time on the problems that arise. He’s been in the profession so much longer than I. Not that he ever tries to run my picture affairs. But he gives me advice when I ask for it. And his advice is always good.”

“Only six times out of ten,” said O’Shea. “I operate on masculine intuition, instinct. You know masculine intuition. Virginia’s the thinker of the family.”

“I think hard about everything,” said Miss Mayo. “I weigh both sides. I think so hard about both sides that half the time I don’t come to any conclusion. That’s where Mike steps in.”

“I don’t think at all,” said O’Shea. “Strictly snap judgments. So when I’m wrong, I really do a job of it.”

“He’s never wrong,” said Miss Mayo stoutly.

“Sugar,” said Mr. O’Shea.

A man came by, rapped on the door, and said something that got Miss Mayo to thinking. She began thinking so hard, you expected to see tendrils of smoke come out of her ears.

“That’s what I mean,” said O’Shea. “It fools people. The other day one of the top executives said to her something about dying her hair platinum for a picture. Virginia sat there with her head in her hands, saying nothing. The guy got a little nervous. Well, not exactly platinum, he said. Maybe more of a wheatfield blonde? Still Virginia says not a word. Or auburn, the guy says. That’s it, of course! In auburn, you’d look great. He’s coming unstrung, see? He thinks Virginia’s mad. So he runs through a whole spectrum until his voice cracks and he dissolves completely. Nah, nah, he says. We’ll just leave it the way it is. Forget I brought it up, will you? So finally Virginia raises her head. ‘I think it’s a good idea,’ she says. Sure, the guy says. Sure it is. Leave it just this way. ‘No,’ Virginia says, ‘I mean the platinum.’ She’d been thinking about it, that’s all.”

So that’s how it is with the Michael O’Sheas, one working steady and the other not so frequently. It’s fine. And that’s how it is with the magazine business, you start with one premise and are diverted to another in deference to the plain truth, and the truth isn’t so bad either.

There’s a happy Irisher with a strong domestic streak in him who likes to fit planks together and repair wiring systems; and there’s a famed and lovely woman who is destined to act in movies, and fortunately that is what the public would prefer she do. They got together and they stayed together. One went down and the other went up and it didn’t make any difference. If at some future date, the trends reverse again, as they well might, that won’t make much difference either.

At the moment, Miss Mayo’s case is the simple one. She is in love, and she is necessarily busy, and she is piling up moo in the practice of her industry and she doesn’t have to worry about the home while she’s away.

O’Shea, too, is in love and reasonably busy, and has developed a great resourcefulness against the possible encroachments of boredom. He lives his part with grace and the gift of being high-hearted about it. If he doesn’t like the doldrums, no one’s ever going to know it—unless his wife knows it and won’t tell. More likely, though, they’re too busy to care.

THE END

—BY JOHN MAYNARD

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE MAY 1953

No Comments