The Saga Of Frederick And Lilly

About two years ago, Bob Taylor gave Snow White to Fred MacMurray. She wasn’t Walt Disney’s Snow White. This Snow White was a Persian kitten. But Fred’s relationship to Snow White is so illustrative of his general attitude toward life that her saga belongs in this chronicle.

Fattened and given lavish affection by Susie, Fred’s little daughter, the kitten grew beautiful. Everyone was happy until the night that Snow White announced at the top of her voice that she craved a personal life.

Fred and his chic and beautiful wife Lillian went into a huddle. It was Fred’s decision that any cat was entitled to her emotions, whereupon they scurried around, found a Persian of as noble blood but the opposite sex, and presently there was a litter of kittens, eight to be exact. Without too much struggle, the MacMurrays found them all good homes.

Thus later on they never gave a thought to Snow White’s barging out on a free-lance job until one morning when they saw more kittens wobbling around their garden.

The MacMurrays went in for some frantic telephoning, but most of their friends weren’t having any more kittens. It was weeks before the new eight were placed into happy homes. Then Fred issued an ultimatum.

“Sixteen is enough for her,” he said. “Let’s have no more of this.” So Snow White went for a visit to the vet and has been as demure as anything ever since.

In everything he does, Fred MacMurray is live-and-let-live, but he believes in reticence and moderation. These latter qualities get in the way when you ask him to talk about himself. It isn’t that Fred doesn’t wish to be cooperative, but he simply is incapable of talking about anything that is important to him. He can talk on for hours about hunting or fishing, but he can’t even tell his wife he loves her.

He has, however, his own way of saying “I love you” to Lillian, as she has for him. He calls her “Lilly.” Lillian’s name stood by her in that way all through her stage and modeling days—her family and friends call her Lillian. But to Fred she is always “Lilly.” She doesn’t like the name, except when Fred speaks it. And she in tum calls him “Frederick.” It is not his name—was never his name. He was christened just Fred. The funny part of it is, he doesn’t like “Frederick,” either! But he loves it when spoken by his wife. He knows it’s her way of saying “Darling.”

Recently a woman friend came to Lilly MacMurray and explained that she could no longer endure her marriage because her husband simply refused to murmur sweet flattery to her.

Lilly shakes her head when she tells this. “Why, if I waited for Frederick to tell me he loved me, I’d wait forever,” she says. “I know that he does, but I’ll never learn it from him in words.” She insists she doesn’t recall Fred’s telling her he loved her when he proposed that they be married, more than nine years ago. To this day, he is still uncertain of just when her birthday falls. He has never yet remembered one of their anniversaries, and he has yet to have the faintest idea of what to give her for Christmas.

“Some of that is my fault,” Lilly says. “I don’t care for jewelry and I make most of my own clothes and hats. I’ve got everything in the house any woman could possibly want, so there never is anything I really do need. But if I don’t tell Fred specifically what to buy for me, he frets and worries and usually tums up with a bag, which I don’t want, either.” She smiles as she says this, the serene and happy smile of a wife in love.

Fred says it was love at first sight for him. “The first thing that got me was her beauty,” he admits frankly. Then he grins. “Now, after ten years, that’s not so important, but I’m glad it’s still there.”

He’s pleased that she doesn’t want to act, either. once Lilly took a screen test. “I thought she was excellent,” Fred says, “but she thought she was terrible. I was thankful for that.”

He talks off-screen much as he does on, one short sentence and then a lull. Off-screen he seems to be genuinely afraid he may get over his depth conversationally, just as he is forever worried he’ll get beyond his depth artistically.

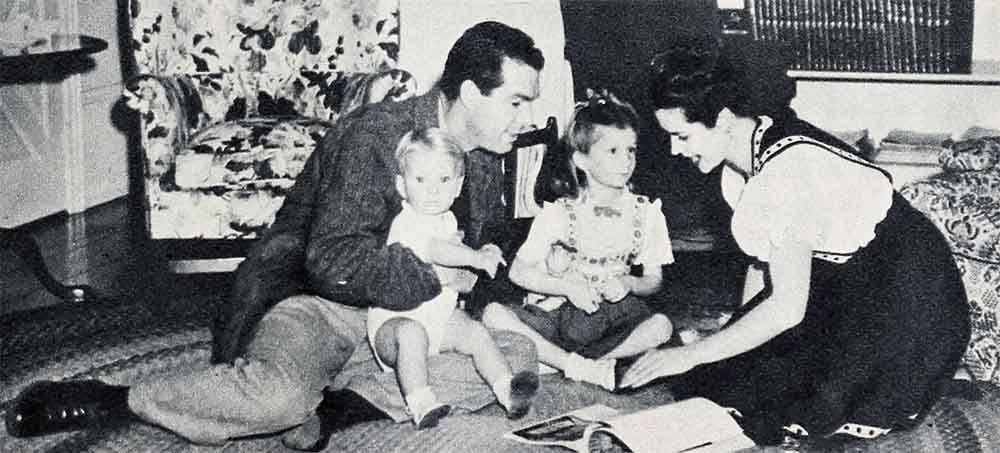

Family fun and contentment—Fred and little son Robert, daughter Susan—and Lillian

Straight from “The Gilded Lily,” his first picture, in which he played Claudette Colbert’s leading man and got $200 a week, up to his present two-a-year contract plus the right to do one outside picture with Twentieth Century-Fox—all three films at many times that original fee—his career has been solid triumph. He just happened to “hit” comedy at Paramount with that first picture, and after that he felt it was all he could do. He made forty pictures there, working incessantly, learning the art that both he and Lilly regard merely as a job, yet he was in jitters over doing “Double Indemnity,” his first straight dramatic part. Every critic proclaimed that it was the finest performance he had ever given, but all Fred says is, “I wouldn’t be so scared now.”

He left Paramount last fail because they refused him the clause Twentieth granted him, the right to an outside picture. This doesn’t mean he wants anything arty. He simply regards that clause as a safeguard against any company’s putting him in too many run-of-the-mill products, which Paramount certainly did. He knows that when companies hire a star, not under contract, at the high figure such hiring demands, they do it only with a fine script in hand. He feels that his newest film at Twentieth, “Captain Eddie,” based on the life of Eddie Rickenbacker and his fabulous exploits in the last war and this, will combine comedy, adventure and drama, a blend he’s never had before.

He has absolutely no fear of the future—Lilly and he having had that planned out all along and having saved accordingly.

“I don’t know why, neither of us being from the country, we always wanted a farm and children,” Lilly explains, “but we talked of getting both from the time we knew we were in love.” They have the farm now, and they call it just that, despite the California tendency to call everything more than half an acre a ranch. There are many acres, situated on the Russian River in the fertile Sonoma Valley near the town of Healdsburg, and already it’s completely self-supporting. Besides that, they own a charming estate in Brentwood.

The Brentwood house is the one that Lilly and Fred had planned down to the last antique doorknob before they were married. It is flawlessly early-American, with open fireplaces in all its small pine-paneled rooms, and furnished with a collection of early American pieces that any collector would cherish. Fred bought them all, prowling around antique shops, though each item was the result of Lilly’s perfect taste and accurate knowledge of the period.

Fred did the buying because Lilly became very ill immediately after their marriage. Meanwhile the house was building, and every night she and Fred would work over sketches of how they wanted the living room, the den, his bedroom, and hers to look, and just where each chair, lamp and rug was to go. In between his studio chores, Fred would shop and bring his purchases back to show Lilly.

When Lilly was well enough to venture out for the first time, naturally the only place she wanted to go was to their dream home. Fred drove her there and carried her over the threshold. There were the rugs, the carpets, the lamps all lighted and the fires in the hearths. It was home and it was beautiful.

Lilly was so happy that very soon she consented to follow her doctor’s orders and allowed Fred to carry her on upstairs and put her to bed. He had to get back to the studio, so fancy her consternation when after his departure she heard workmen rushing around downstairs.

She soon learned why. The doors weren’t really up. The floors weren’t finished. The windows weren’t all set. But Fred had had the whole thing put together, from the doors temporarily on their hinges to the window frames in place, just to give her that first fine look at it.

The house isn’t big enough now that their children are there, so they plan someday to add on rooms to accommodate them. They have two children now and they want six. “Why not?” says Fred. “The more the better!”

These first two children are adopted. Susie came first, because first Fred and Lilly wanted a little girl. She is very blonde and blue-eyed and tall for her age and they think she has pronounced musical ability. Not yet five, she has an enormous collection of records, largely classical, which she plays constantly. She memorizes the words of any song she hears and when she doesn’t entirely remember a musical phrase, she will stop the record at that point and go back again and again to that one spot until she does.

Robert Scott MacMurray is fourteen months old, and is just as blond and blue-eyed as Susie, but does, by happy accident, look like Fred. There is no reason for his given names except that Lilly liked the name of Robert and Fred liked the name of Scott, so they combined them. “I wouldn’t wish any kids into being Junior,” Fred murmurs. They’ve had Robert ever since he was four days old, but they have never talked of him until recently. “Wanted to be sure we had the pink slip on him,” is the way Fred puts it. As soon as another girl baby comes along they’ll take her. They still very much hope to have children of their own, but regardless, they’ll have six, and if they adopt them all, there will be three girls and three boys. “I’m sure I couldn’t love my own any more than I do the two we’ve got,” Fred declares.

“I’m glad they are going to be tall,” Lilly says, “for we’re tall people. I only hope they won’t eat as much as Frederick does.”

She insists it wasn’t love at first sight with her, but when she describes her reactions she makes it sound, at least, like a very good substitute. She says that when she was introduced to him he was one of the worst-looking creatures she had ever seen. “He had on a dripping hat and a dripping overcoat, because he had just come in out of the rain,” she explains, “and he’d been working so hard his face was haggard and his eyes were tired. Just the same, I knew I liked him better than anyone I’d ever met.”

They began dating immediately, but what threw her was not only his appetite but his genius for cooking. Lilly knew very little about cooking then, but while Fred knew nothing through cook-book learning, instinctively he was a master chef.

“Every time we’d have a date,” Lilly says. “I’d dig out the most beautiful recipe and prepare it with such care, and then Frederick would arrive, taste the dish and say, ‘It needs just a dash’—and he’d put in the dash of whatever it was, and he’d always be right. But my heavens, there was no filling him up. He’s kept it up until just recently. Now he’s tapering off a bit, but at least I’ve learned to cook almost as well as he.”

All their closest friends love food. Their immediate pals are Ann Sothern and Robert Sterling, Mal and Ray Milland and, before their split-up, Ann Dvorak and Leslie Fenton, whom they now see individually.

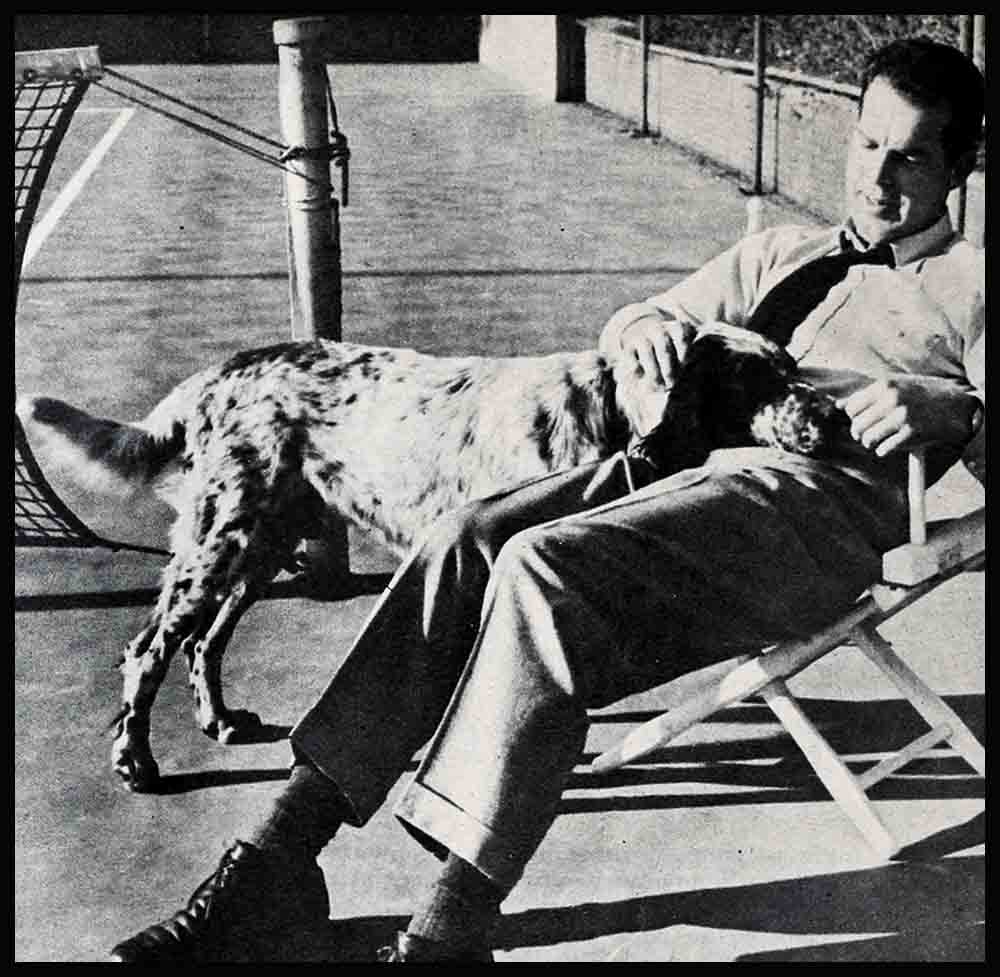

Besides quiet evenings spent with this set playing parlor games, Fred likes to go off on hunting trips with some men friends from the neighborhood. At least he did before the war, when he had the gas for it. Now he hasn’t. Lilly never goes with Fred on these trips—not only because she’s no outdoor girl, but also because she recognizes the call of that peculiar male world wherein men like to get bearded and go dirty and live on steaks cooked in the open and sleep on air mattresses thrown on the ground.

“He goes on those trips and comes back looking like a tramp,” Lilly says, “but you never saw anyone happier.”

Fred may not be demonstrative, but he is one of those husbands who is a wizard around the house. No electricians and no plumbers appear at the MacMurrays for Fred is right there to fix up anything that needs repairs. He has his own workshop, out in back of the house, and there he can even turn table legs or create new bookshelves, if such is needed However, last Christmas he decided, with a bit of urging on his wife’s part, to he even more domestically helpful. The MacMurray Christmas list runs to the colossal amount of three hundred individual presents and Fred told Lilly he would help her with the buying and wrapping.

“Oh, fine,” said Lilly. “Why don’t you take the men and I’ll take the women.”

They started off together to shop, Lilly heading off toward one department and Fred the other. Lilly got ten gifts, felt tired and went to the spot in the store where they had agreed to meet. No Fred. Figuring he was really digging into the list, Lilly got slightly ashamed and returned to the ladies’ department, got five added gifts and went back to the front of the store once more. Still no Fred. She sat and waited and finally she saw him struggling toward her. In his hands she saw exactly two packages.

“What happened?”

“Autographs,” he said hollowly. “Let’s get out of here.”

Safe in the car he said, “Well, I did get these two gifts, anyhow.”

Back home, Lilly opened them up. With stunning originality, Fred had bought one man a tie, the other some handkerchiefs.

She wasn’t discouraged about the gift wrapping, however. Together they sat in the middle of their living-room floor, the packages about them. They were doing up gifts for the numerous children Susie and Robert play with. Very carefully Fred wrapped up two of them. Then he raised his head. “Lilly,” he said, “I’m afraid I’ve mixed up these cards. Do you know which kids these packages are for?”

“It doesn’t matter, dear. They are both dresses. One’s for Barbara Binyon (the writer, Claude Binyon’s little girl) and the other’s for Julie Payne.”

Fred threw her a worried look. “Maybe you’d better be sure.”

To please him, Lilly undid the package in which he’d put the card for Barbara. Only it didn’t hold a dress. What Fred had put in there was Danny Milland’s pants.

Well, maybe he doesn’t tell Lilly he loves her, but you gather the idea, don’t you, that he’s a typical American husband, which means, as every woman knows, the best brand of husband there is.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MAY 1945

No Comments