“Is It Wrong To Feel The Way Me Do?”—Joanie Sommers & Bobby Rydell

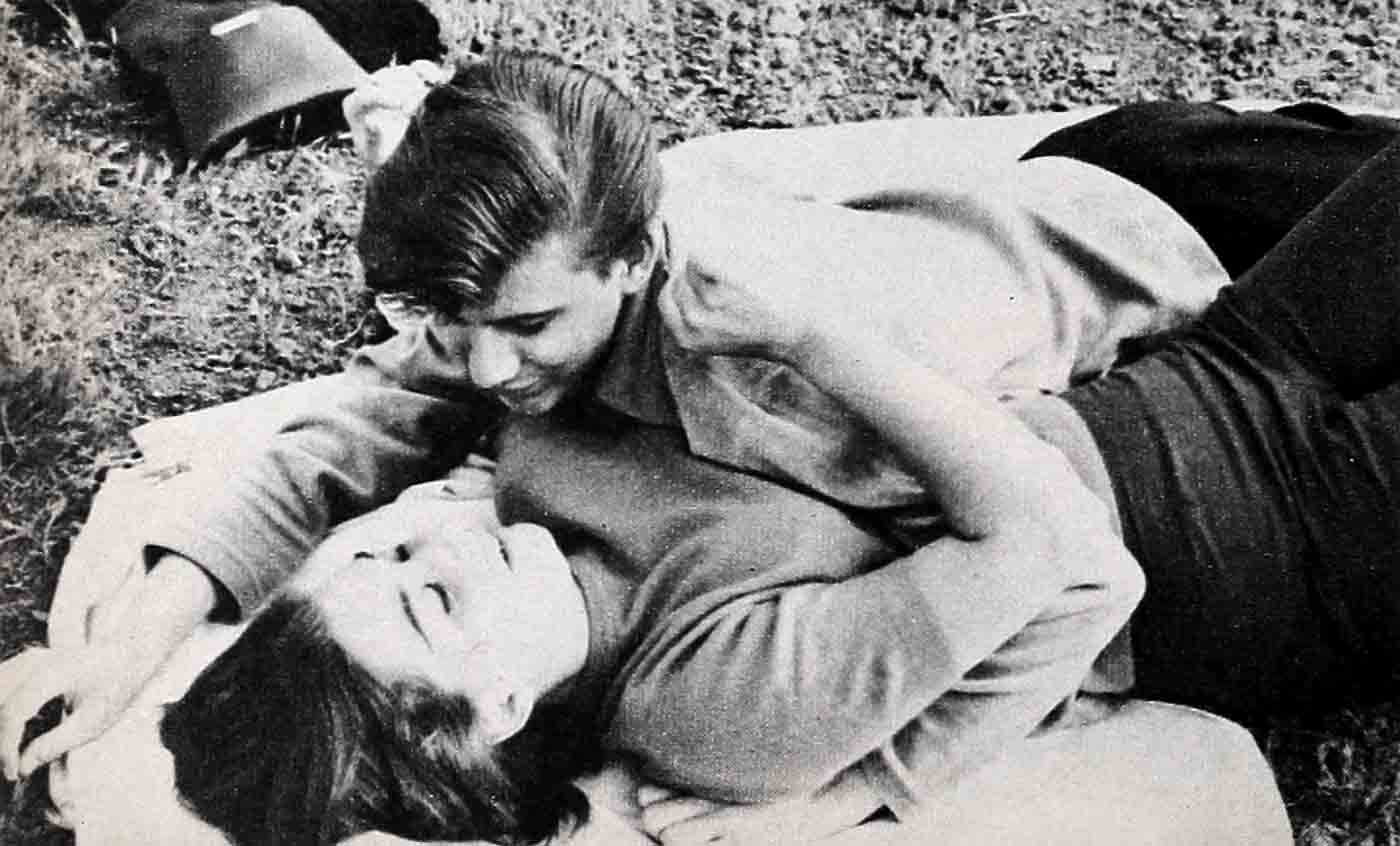

Tumbling and giggling, they rolled on the ground, a tangle of arms and legs. For a minute they lay there, Bobby’s arm around her waist, his head resting on her shoulder as he tried to catch his breath.

“He’s so crazy,” she thought, “and such fun.”

Almost as though he’d heard, Bobby lifted his head and stared closely at her. She didn’t know why, but she felt her face flush and a funny lightness in her head when he tightened his arm and, suddenly feeling shy, she twisted to one side, sat up and pretended to pin back her hair that had fallen loose when she fell to the ground. It was her fault, really, that she fell.

“Race you to the clearing,” Bobby had said with a mischievous grin as they reached the top of the hill, and they were off.

She noticed he held back a little to give her a head start but, even then, he got there first. It was lucky he did, too, because just as she reached him she slipped on a broken twig and when Bobby tried to catch her they both fell.

As she sat there, in the middle of Griffith Park, she was glad she had come. She wasn’t sure when Bobby called yesterday. She really didn’t know him that well. Some mutual friends had introduced them. But he began to joke on the phone and so she gave in. They had first met at the park a month ago and Bobby had had her within minutes floating on air . . . well, almost. . . . They were sitting near the trampolines—which were the big thing in California—and when she admitted she’d never been on one, Bobby insisted, right then and there, on teaching her how to jump on one of them.

Before she knew it she was standing several feet above the ground, ankle-deep in canvas, having her first lesson. It was real tricky but she was good at sports and caught on pretty fast.

“Gee, Joanie, you were great,” Bobby said as he lifted her down. “How about a soda?”

“Well, maybe some coffee,” she said thinking about the diet she had started just that morning.

Her mother said she didn’t have to lose weight but she was always going on crash diets anyway.

As they walked toward the ice cream shop, they passed four girls who stopped when they saw Bobby and then came running after him.

“Please . . . can we have your autograph?” the tallest asked.

“Sure,” Bobby said with a big grin, and immediately all four surrounded him.

“Here, you better use this,” Joanie offered, holding out her pocketbook for him to lean on.

Afterward, when they were sitting in a booth in the ice cream shop, Joanie looked down at her pocketbook. “Look!” she laughed and held up her bag. “Those girls weren’t the only ones who got your autograph.”

On the flat surface where Bobby had leaned, you could read: “All the best, Bobby Rydell.”

“Gee, maybe I should preserve it in bronze,” she said pretending to be serious, and then started to giggle, “. . . and dedicate it to The Man Who Bounced Me off My Feet.”

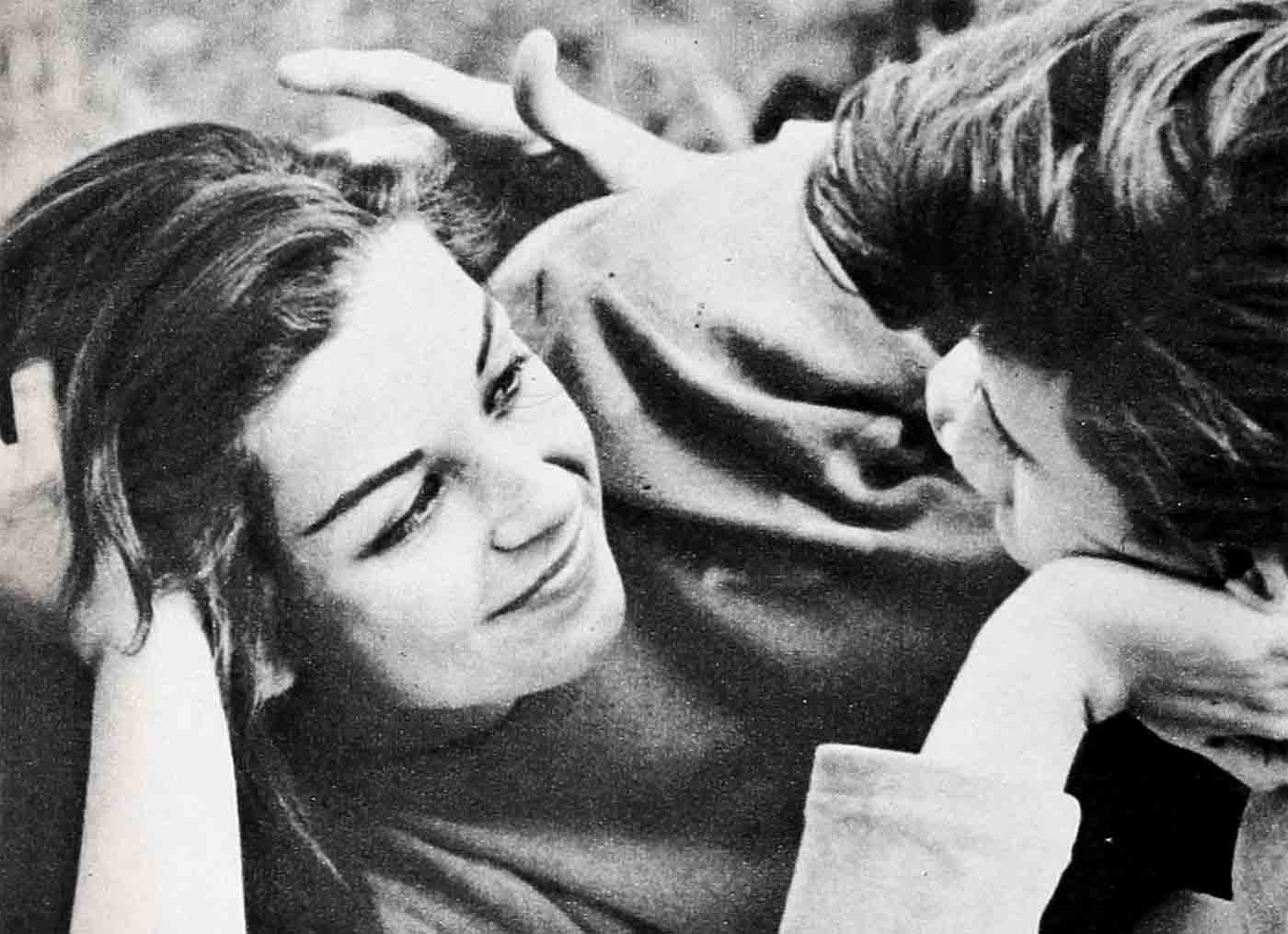

She didn’t realize she was smiling, now, as she remembered until she felt a piece of grass tickle her right cheek and heard Bobby say: “Penny for your thoughts?”

“They’re secret,” she smiled and looked over to where he lay, stretched out full-length on the hill. “He looks longer than five feet nine,” she thought to herself. She knew exactly how tall he was. That was one of the first things she asked about a boy because, even though she was only five feet three-one-half, she liked to be able to wear heels on a date and still have the boy taller.

“You know, I’m supposed to be home working on a new arrangement today,” Bobby said, “but this is much more fun.”

“Me, too,” Joanie said guiltily. “I feel as though I’m playing hookey,” and they laughed together.

Bobby took a deep sniff of the air and cradled his head in his hands. “Look at those clouds,” he pointed. “Sheep-in-the-meadow.”

“Do you call them that, too?” Joanie asked, her voice squeaking a little in excitement. “My aunt—the one I used to spend summers with—did, but I’ve never heard anyone else call them that.”

“My grandmother used to,” Bobby said leaning up on his elbow, and they sat, grinning at each other as though they’d just discovered something terrific.

“Where’d she live?” Joanie asked.

“Actually we all lived together in our house in Philadelphia but my grandparents had a cottage at Wildwood that’s down on the Jersey shore. And ever since I can remember, we went there summers.” He rolled over on his stomach and started chewing a blade of grass. “We had great times. Frankie Avalon used to stay with us a lot. Do you know him?”

“I’ve gone out with him a couple of times,” Joanie answered, “but I didn’t know you grew up together.”

Bobby nodded. “There used to be a saying around home that you could stand at the corner of Thirteenth and Ritner Streets—that’s right near where I lived in South Philadelphia—and hit Mario Lanza’s house and Eddie Fisher’s house with the same stone, but now they need a lot more stones. Jimmy Darren lived right back of me, Frankie lived three blocks away and Fabian only one. Frankie, Fabe and I went to the same boys’ club.”

“Did you all want to be singers then?” Joanie asked him, a little curiously.

“Did we!” Bobby laughed. “I think we were born that way. Frankie and I were playing at weddings when I was twelve and we got our real break the summer I was fifteen. We were in Atlantic City and went to hear a band, ‘Rocko and His Saints’ they were called, rehearsing. When we got there we found out two guys were sick so we filled in for them. Somebody forgot to ask us how old we were and we got their jobs. I played drums and Frankie played trombone. In between, we did a kind of song-and-dance routine that we’d worked out ourselves. It was kind of funny,” he said, flopping down again on the grass beside her, “later, after Frankie and I began making personal appearances, fans used to write both of us warning us that the other was stealing our dance steps . . . but it was that same step. We just didn’t know any other.”

He smiled sheepishly. “I guess there’s some ham in me,” he admitted. “I always loved to be on stage.”

“Not me,” Joanie burst out so violently that Bobby was startled. She was usually so soft-spoken. “I hated it,” she said. “I used to sing with my high-school band and every time I had to get up there I’d just die. I’d be so scared, I’d be stiff as a board and when I heard them playing my introduction, and I’d think: ‘What if I get out there and I can’t sing anything?’ Crazy, huh?” she laughed.

He hadn’t seemed shy

“You like it now, don’t you?” he asked and she nodded yes, adding: “Maybe, someday, I might even like to try acting—but not right away.”

“Boy, that’s what I’d like to do,” Bobby said, his eyes bright with excitement, “. . . make a picture. I’d give anything to be a well-rounded performer like Sammy Davis, Jr. He’s great at everything . . . singing, dancing, movies, night clubs, impersonations. . . .”

“Can you do impersonations?” Joanie asked.

He answered by sticking his chin way out, curling his lips and saying: “Okay, you guys, line up over there,” gesturing with his head.

“Edward G. Robinson?” she asked hesitantly.

“No,” he answered dropping his chin back down.

“Oh, I know, I know, Cagney . . . James Cagney,” she shouted.

“Right,” he said with a pleased smile.

“Honest—I didn’t know you could do that, too,” she said.

“Oh,” he said in an off-hand manner, “it’s nothing really. I’ve been doing them since I was nine.” Then, more seriously, “The first amateur contest I ever entered I did impersonations and sang. Everybody laughed when I came out on the stage because they couldn’t get the mike down low enough for me. But I learned something very important that day. I used to be awfully shy as a kid—I guess I haven’t gotten over it completely, yet,” he admitted and Joanie thought, somewhat surprised, that he hadn’t seemed at all shy with her today.

“But I used to be afraid to even talk to people sometimes,” he went on, “until that day when I heard all those people cheer- ing and shouting for me. I felt as though I was someone else . . . not just skinny little Bobby Ridarelli.” He paused, then quickly asked: “Did you ever hear me doing Bobby Rydell’s interpretation of Bobby Rydell playing the drums?” And he began to beat out a frantic solo on an imaginary drum.

When Joanie giggled, he said: “I can see you don’t appreciate it, but I can tell you it went over big in Wildwood, New Jersey.”

There was a big open area under the porch of his grandmother’s house where he and Frankie Avalon used to put on two-man shows for the kids—every afternoon at 3 o’clock—impersonations, drum and trombone solos, and songs… all for a nickel that they never could collect. They used to play in their bathing suits so they could run right back down to the beach to swim or play baseball, and then his mom would have to come down and drag them home for dinner.

“We never wanted to take time out to eat . . . no wonder we’ve both never been able to gain any weight,” Bobby said. Then, with a self-conscious laugh, he apologized shyly: “Gee, Joanie, I don’t go on like this all the time. I don’t think I’ve ever talked this much about myself to anyone.”

She felt flattered, as though he’d paid her a compliment, but she just said fliply: “Oh, I enjoyed it.”

“I’ll give you the next two hours,” he said, leaning on his elbow. “What about you?”

“Oh,” she said, playing with the collar of her jacket, “there’s nothing much to tell.” She felt her mind go blank the way it did whenever someone said: “And what have you been doing lately?” She could never think of anything terribly interesting to say.

“Where’d you live when you were little?” he asked.

“Buffalo,” she answered, thinking, he’s so nice and friendly he probably does want to know about me. “And then we moved to California . . . to Venice . . . when I was in high school and I lived there with my parents.”

“Which do you like better,” Bobby asked, “Buffalo or California?”

“Oh, both,” she said. “I go back to Buffalo to visit a lot, but if we hadn’t moved here I probably would never have become a singer. I’d always loved to sing, but it was just for fun. I’d never taken lessons or anything . . . in fact, I still haven’t. I guess I kind of want to see how far I can go on my own. And so I would never have had the nerve to try to sing professionally if it hadn’t been for Tommy Oliver.”

“The band leader?” Bobby asked.

How it started

She nodded. Tommy Oliver played at their farewell dance when she was graduating from Venice High and toward the end of the night, a couple of the students started fooling around with the band, playing drums and singing. Then someone called her over to join in and after a couple of minutes she realized everybody else had stopped singing and she was doing a solo with the band. Somehow, she managed to finish the song, and then Tommy asked her to sing some others, and afterward he said he’d get in touch with her. She thought he was just trying to be nice but that fall, after she’d started classes at Santa Monica College, he called and asked how she’d like to sing with his band.

“And that’s how it started,” she smiled and shrugged her shoulders. “I kept on at College and sang with Tommy weekends and then, one day, he took me down to Warner Brothers Records and they signed me up that very day. I nearly flipped. In fact,” she laughed, “sometimes I still have to pinch myself to believe it’s all true.

“When I was a little girl, I used to dream about being a beautiful and famous singer and I always pictured myself standing up on a stage in a white organdy evening dress with a big wide skirt. But even then, I didn’t dare admit it to anyone. Except once,” she corrected herself. “That was when I heard there was going to be an amateur singing contest at one of the movie houses in Buffalo and I persuaded my mother to let me enter—and I won!” She wrinkled up he forehead and said: “Isn’t that funny? I can’t remember what I won . . . a plate, or something.”

“Did you ever think about whether or not you’d want to keep on singing when you get married?” Bobby asked.

“I don’t know what I’d do,” she said thoughtfully. “That’s why I don’t want to get married for a long time.”

“Me, neither,” Bobby agreed and they both sat thinking. “But I sort of know what kind of girl I want to marry,” Bobby said. “Someone who’ll feel the same way about things as I do and who will understand me,” and then he grinned. “And of course she’ll have to be smart, pretty, have a good sense of humor, like kids and be able to match my grandmother’s Italian cooking.”

“That’s all?” Joanie laughed. “All I want is for him to be tall, have dark hair—although that’s not really important—be a good conversationalist. . . .” With an embarrassed laugh, she tilted her head and looked at him. “Oh, this is silly. It’s only a dream.”

“What’s wrong with dreaming?” Bobby asked. “I have two favorites. I can never really decide between wanting to be Leonard Bernstein conducting a full symphony orchestra—with everyone in white tie and tails, of course—at Carnegie Hall, or having a jazzy red Thunderbird.”

“You know what I wish?” Joanie asked. “I’d like an unlimited charge account at one of the biggest stores in every city in the country—I never seem to have enough money for clothes—and lots and lots of pots and pans. But not the ordinary kind,” she said, sitting up straight on her knees and leaning forward excitedly. “I want the kind with copper bottoms—for our new apartment.

“You know,” she said, shaking her head seriously, “it takes a lot of furniture to fill up even a one-bedroom apartment. I don’t even have a record player. When I want to hear my own records, I have to borrow one from a neighbor. That’s next on the list . . . after the pots. They’re most important because I love to cook,” and, with a groan, added: “As you can see, I love to eat, too, but I think the real fun of cooking is to experiment—you know, Mexican, Chinese, Italian foods—but you need lots of pots to do that,” she said wistfully.

“How are you on meatballs and spaghetti?” Bobby asked, leaning toward her.

“Oh, just great,” she answered and added with a mischievous grin, “but not as good as your grandmother, I’m sure.”

He laughed and then quietly motioned to her to look toward the edge of the woods where a small squirrel was busily rubbing his face. They watched until he scampered off behind the trees.

“There were lots of squirrels and wild rabbits on my aunt’s farm,” Joanie said in a soft voice, “and there was a hill, too—a little like this one—that was my wishing hill. I used to go there whenever I wanted something real bad, like a new bike or roller skates or a new dress for a party. And when I was really unhappy or depressed,” she added in a voice so low he had to bend his head to hear, “I’d go there at night after it was dark and no one was around and sing until my lungs gave out. Singing always made me feel better—it still does.”

“But . . . but why,” Bobby asked, stumbling a little, “why should you ever feel that way? You’re so pretty,” he said shyly, “and you’re doing what you want to do. I should think you’d have everything you want.”

She sat, chewing on the tip of her thumbnail and then, without intending to, she found herself telling him something she’d never admitted to anyone. “Oh, I . . . I embarrass me all the time,” she blurted out, then stopped, and blinked quickly, before the words started spilling out, the way they always did whenever she was nervous.

“I want people to like me”

“I guess I just don’t have enough confidence in myself, or something, because I’m always worried about how I look or if the person I’m with is having a good time or whether I’ll have trouble talking to someone I don’t know very well. And sometimes I worry that maybe I hurt people’s feelings—I don’t mean to but there are some things, like gossiping or putting on a big act, that I just don’t like and I can’t pretend I do. I want people to like me, but I want them to like me for what I am.”

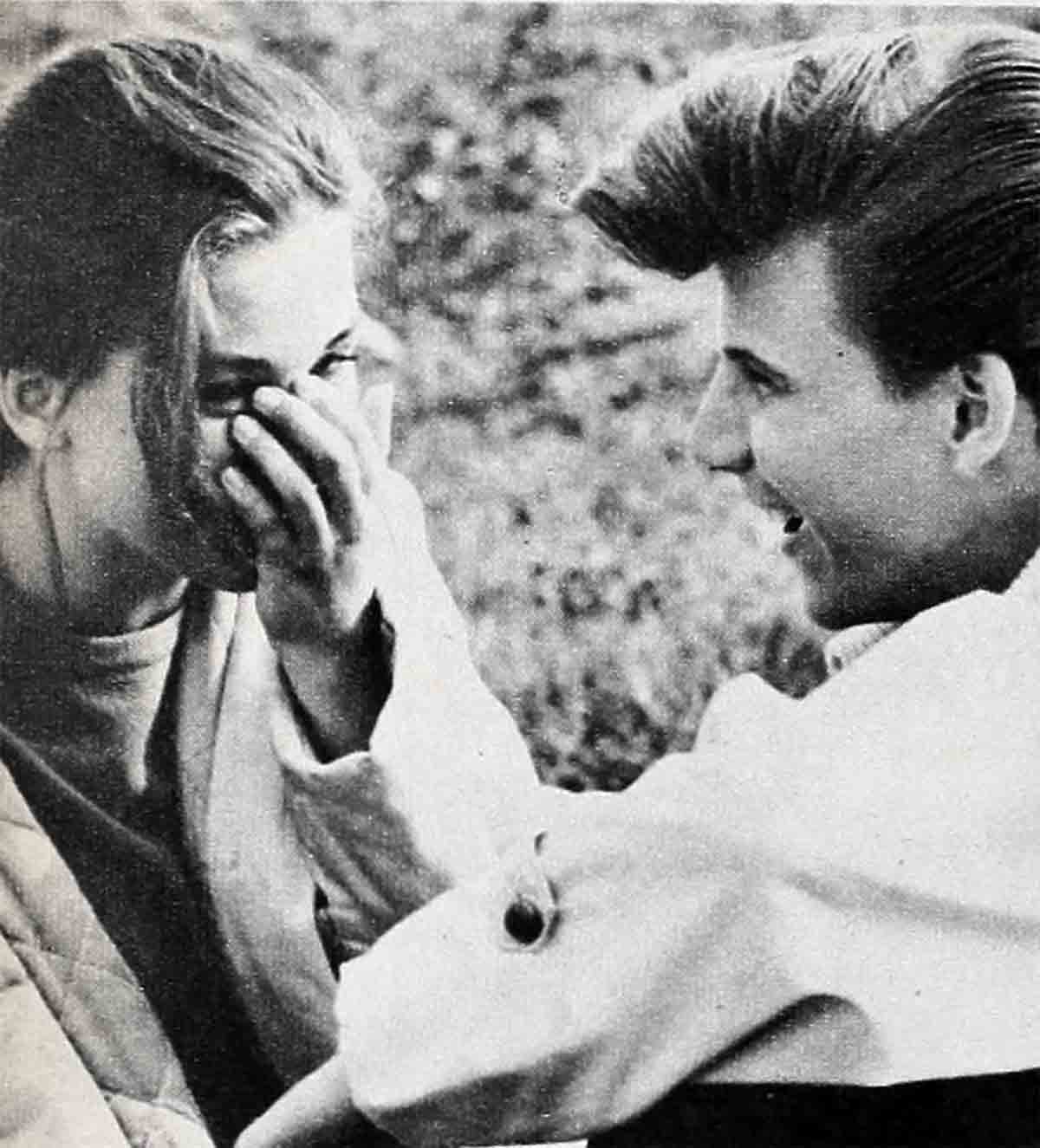

She stopped talking, embarrassed over her outburst, and looked down as Bobby reached and gently took her hand. Instinctively, she started to pull it back, but Bobby didn’t seem to notice and he started to talk.

“I know what you mean,” he said. “I used to feel that way lots of times, too,” he said, and realizing he had understood what she had been trying to say, she relaxed and let her hand rest in his.

“Il remember once, especially, I had a crush on a girl. She was the smartest and most popular girl in my class and it took me a whole semester to get up enough courage to ask her out. I never expected her to say yes and I almost wished she hadn’t, because I was so nervous, I couldn’t think of a thing to say the whole night. I even stumbled saying goodnight when I took her home. I remember going home and sitting down behind my drums. It was after 12:30 so I couldn’t really play, but I sat there for about an hour, beating out a rhythm with my fingers and the brush, pretending I was doing a solo on a big stage before a packed audience. Of course, the girl was there, applauding like crazy.”

They didn’t look at each other, just sat staring out across the clearing. She felt so close to him, she wished she could let him know how she felt. “Boys always act so sure . . . so confident,” she said. “If only you’d let us know . . .”

Bobby turned and looked directly at her. “Maybe it’s because we can’t talk this way to many girls,” he said finally. “They’re not all understanding . . . not like you,” he added and, reaching over, touched her cheek gently.

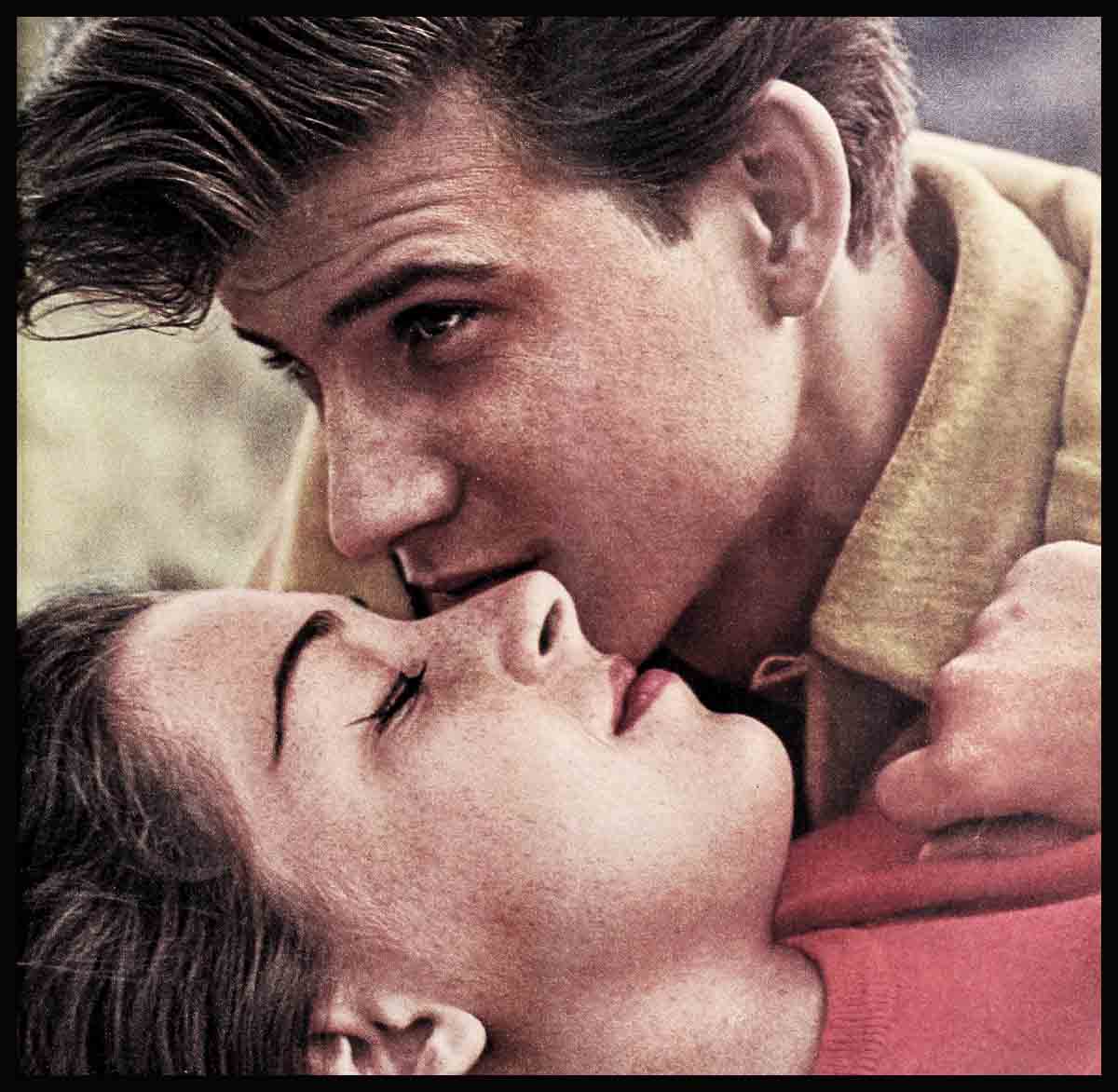

She didn’t know if she just imagined that he started to lean toward her but in some strange way she knew that he felt the same closeness she did and she also knew that it was time for them to go.

Hesitating to break the mood and not wanting to offend Bobby, she touched his hand briefly with the tips of her fingers and said: “Today was a very special kind of day, Bobby. I’ll always remember it.” And, then, trying to lighten their mood, she added: “But how could I forget? I have your autograph here on my pocketbook to remind me.”

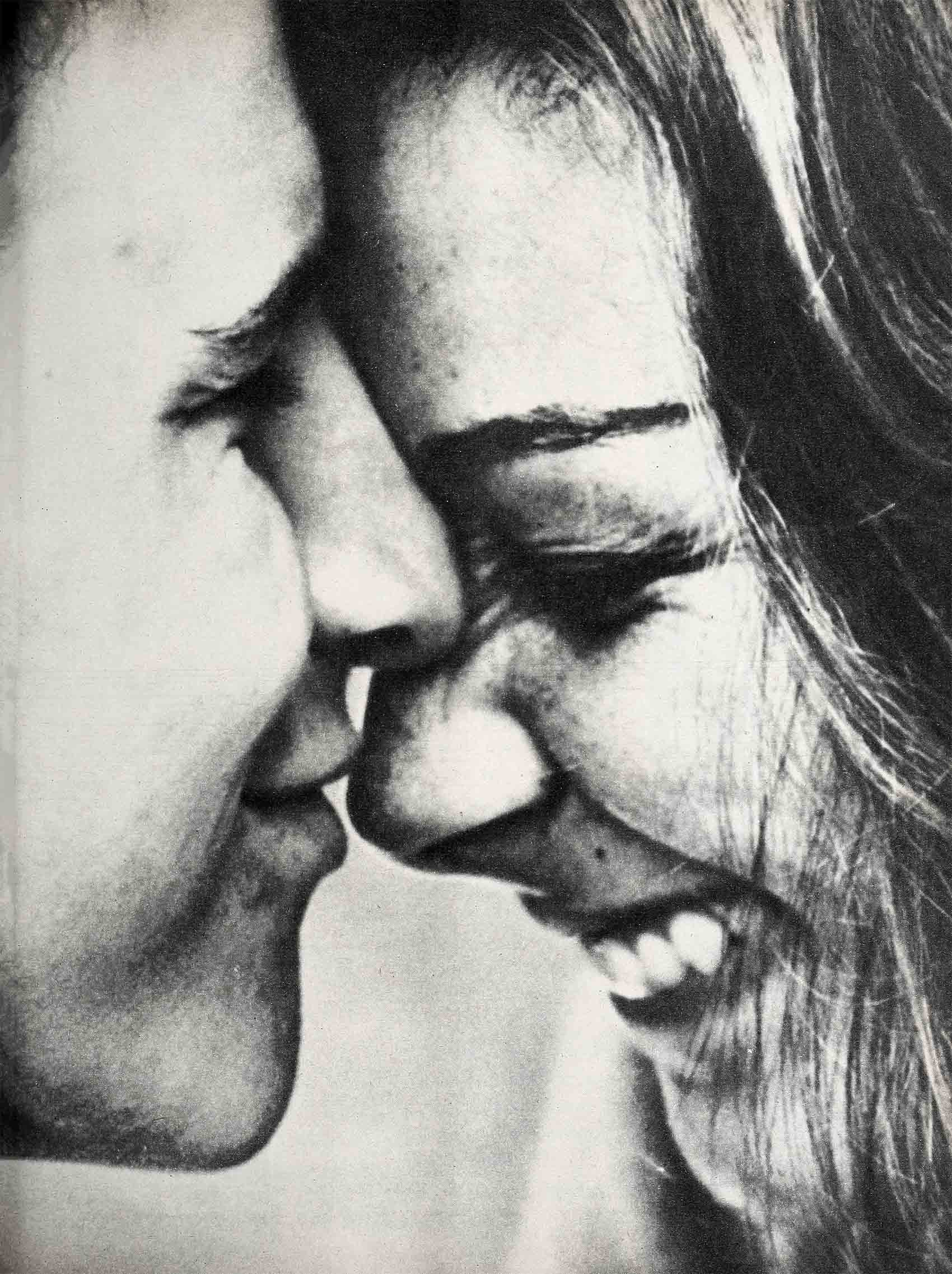

She started to get up and Bobby leaned forward and quickly kissed her on the tip of her nose. “Will you go out with me again?” he asked.

“I’d like to,” she answered, and smiled as she realized that he had understood. Impulsively, she slipped her hand into his and they started to slowly walk back through the park.

—BY G. DIVAS

Bobby sings on the Cameo label. Listen to Joanie sing on the Warner Bros. label.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1960