The Reluctant Traveler

WITH A SCREECHING OF WHEELS in the cold early dawn the Oriental Express stopped inside the border of Yugoslavia. A hundred yards away was Greece, but before they could reach there, Alan and Sue Ladd had to face a glowering Yugoslavian official. “You cannot cross the border without papers,” he snapped.

“But nobody ever returned them to us,” Sue, who can speak German and French, explained patiently. According to instructions, the travelers had filled out two originals and two copies for Customs, had given them to the porter. He had never given them back, Sue said. We have to get to Greece, she went on. My husband is an actor . . .

AUDIO BOOK

“Please,” the official interrupted impatiently. “You will get dressed. You will get off the train.” As Sue and Alan Ladd looked at each other in dismay, then out the window at the bleak, unfriendly countryside. “What,” Alan mused, glancing at the official speculatively, “would Errol Flynn do now, I wonder?”

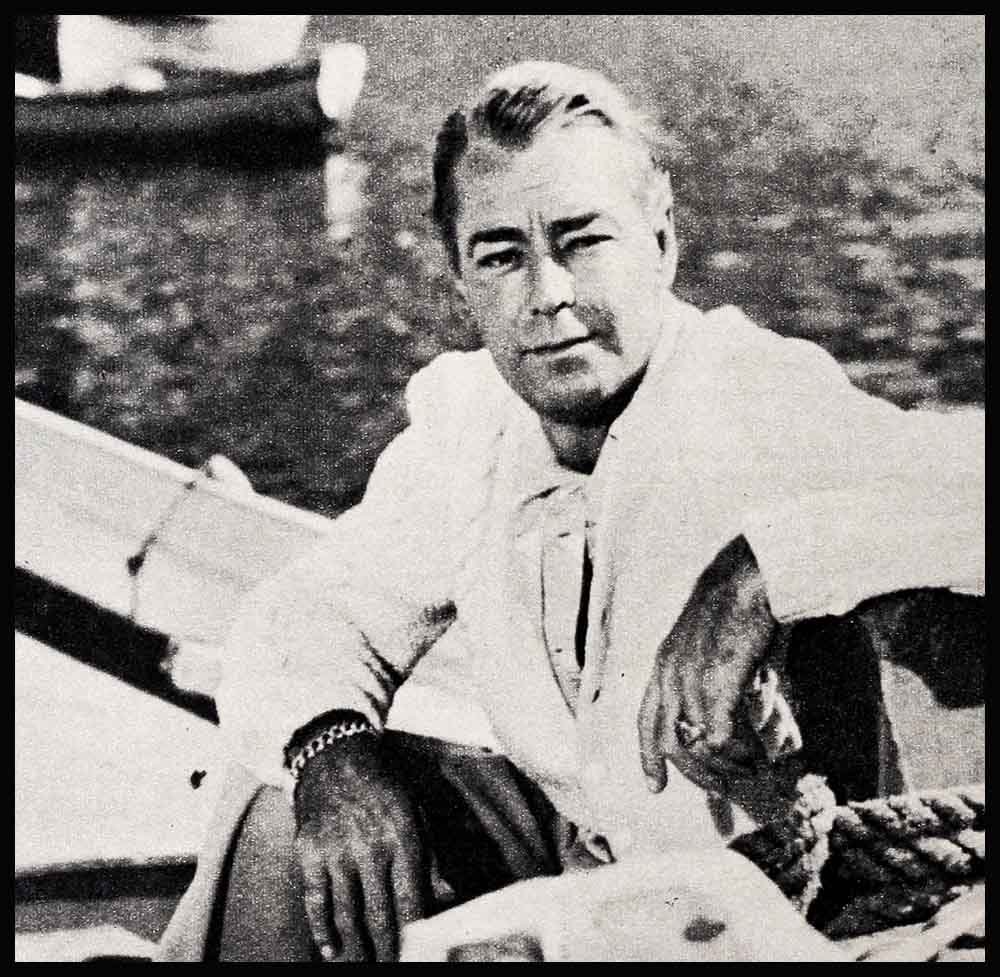

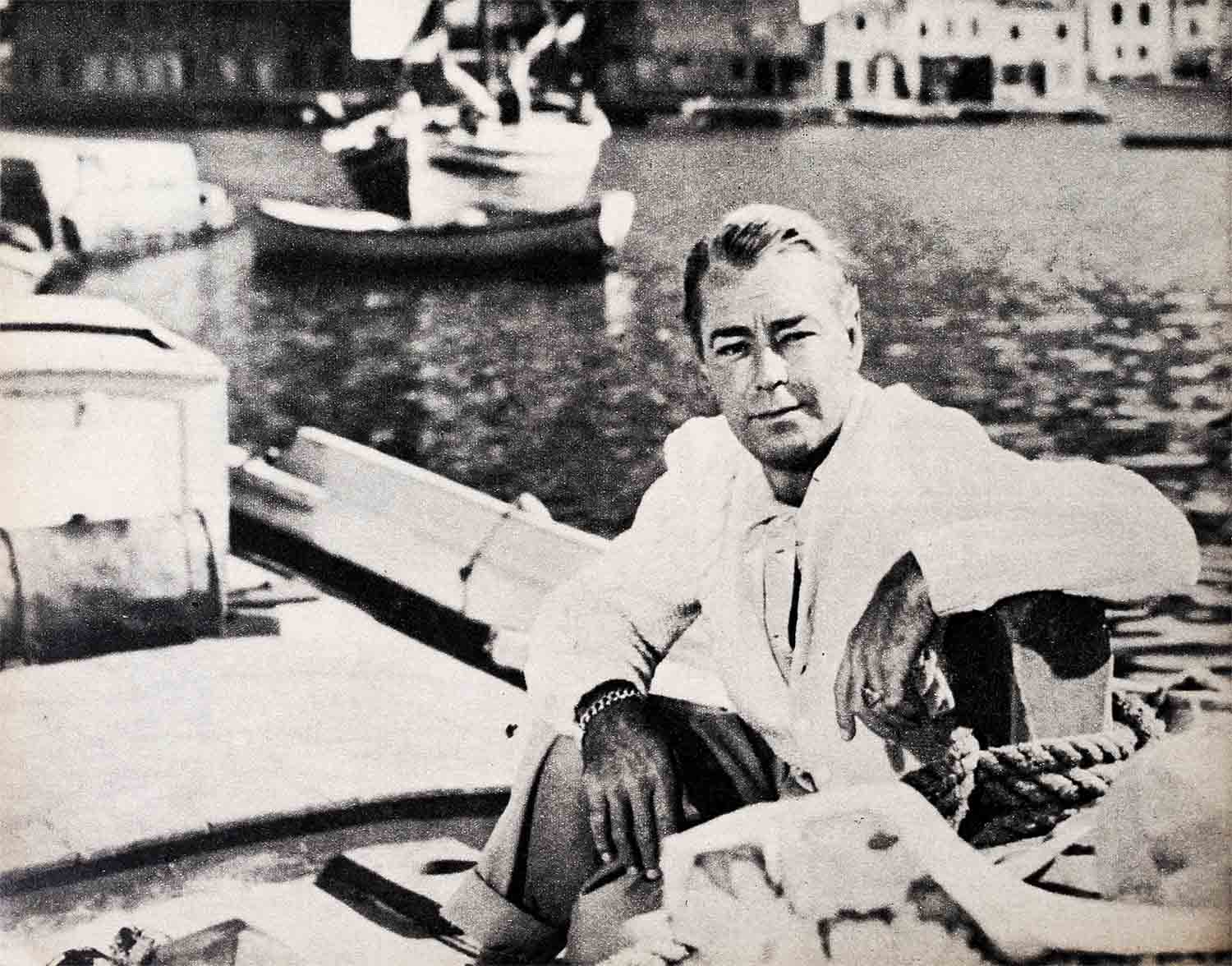

But it was not really a laughing matter. Not for Alan. This reluctant traveler, on his way to Greece to make “Boy on a Dolphin” with Sophia Loren and Clifton Webb, might well have asked himself, “What in the world are Sue and I doing here?”

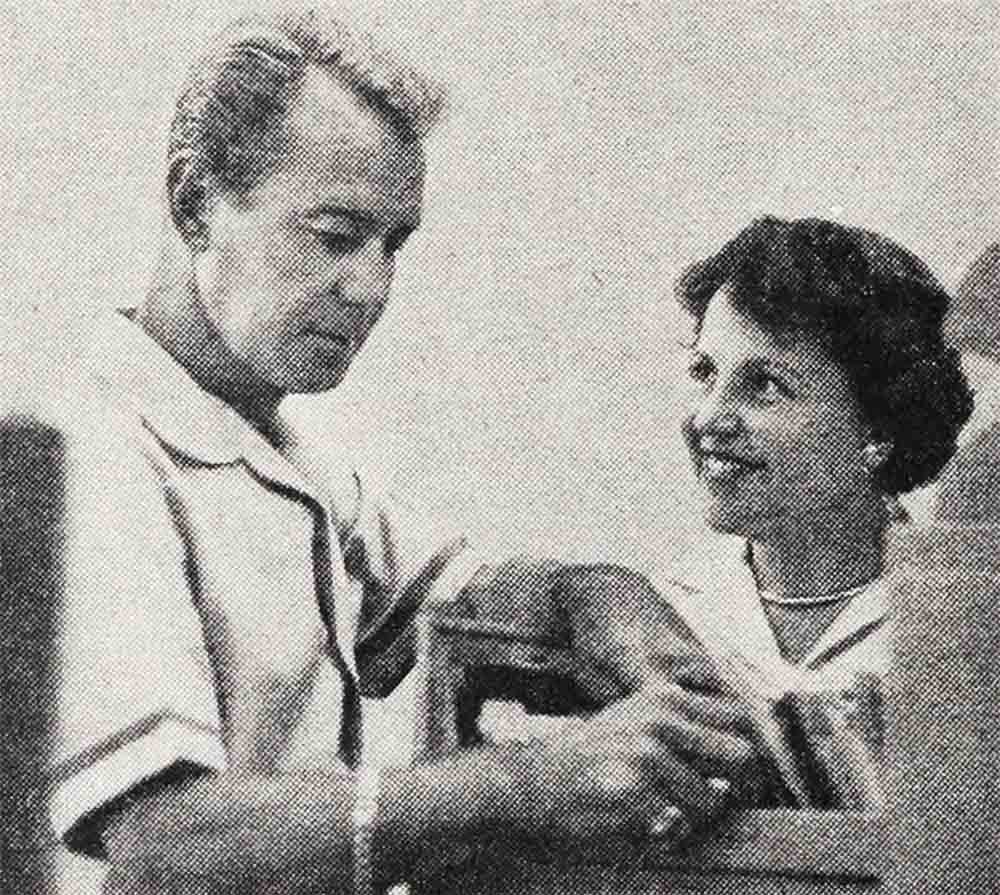

Faraway places hold no attraction for Alan Ladd. Adventure is his meat professionally, on the screen; but off it there is adventure aplenty for him in just following the sun from the studio at the end of a day to the Ladd home in Palm Springs. An exciting script, a strong role, an excellent cast—they are alluring enough to get him moving, to take him far from California and into strange climes. But even they would not be enough if Sue weren’t able to be with him, if he couldn’t take along the heartbeat of his home and family.

“I’m not too adaptable that way,” Alan admits. “Once my roots are planted, I don’t want to move.”

Sue, too. “Greece?” she had said uncertainly, when 20th Century-Fox announced that the whole picture would be shot abroad. That meant a long stay.

“Greece!” Alan had replied, and had begun getting homesick immediately. “I always want to come home before we even start,” he admits. “I just don’t like to go anywhere I’ve never been before.”

Nor had it helped, this trip, to know that they would be gone three and a half months—during school months, when the family couldn’t go along. That they would be on location in the Aegean Sea off a rocky little island called Hydra, on which there were no housing facilities available. That they would be living aboard a 112-foot yacht rented for them by the studio. For one thing, Sue has a sad way of getting seasick on boats.

And now, as they sat in the stalled train for four long hours while the Yugoslavian officials debated whether it was really necessary to put them off, even their temporary yacht home seemed hopelessly far away. At last a friendly Greek fellow passenger managed to impress the Yugoslavs with the fact that Alan Ladd is a famous American cinema star. That taking him off the train would be a mistake. “It would create quite an International incident,” the passenger pointed out. That was enough, and the train finally rolled across the border and on to Athens.

There, it seemed, half the population of the country was waiting for them. “It was so different!” Sue recalls. “They are a happy people, and they knew Alan. They met us at the train with Greek dictionaries and all sorts of gifts. The crowd practically carried us to our car.”

Their floating home was called “The Daphne,” a former patrol boat, and was anchored off Hydra, which is a quaint island community built on rock, with cobblestoned streets and houses stacked in pastel-colored tiers, one straight up above the other. It is four hours by boat from Athens, completely isolated, with no telephones.

Sue was to discover that she was a better sailor than she had suspected. “For some reason she couldn’t take the little motion of a big boat,” Alan explains. But in a rough sea there was nothing little about the way the “Daphne” moved. “When we were in heavy water this boat would rock and roll, furniture would dance around and tables would go smashing from one side to the other—yet it didn’t bother Sue at all.” As for Alan, he could even do his calisthenics aboard her. “I’d go out in front of the masthead and do handstands, with the boat jumping under me like a bucking bronco.”

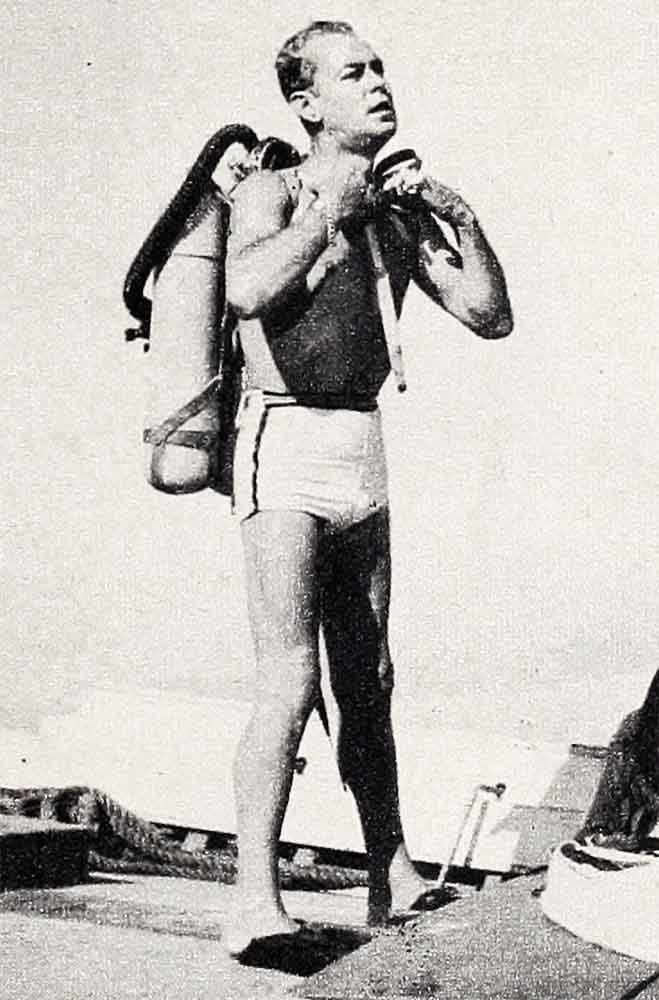

An aquatic home has its novelties. Alan, a former free-style swimming and diving Champion, could dive the twenty feet over the side in the morning and swim to work; the camera barge was usually about 200 yards away. Alan and Sue had a charming suite, including a big bedroom with full-sized bed, a den and a gray marble bathroom. Above that there was a dining room, card room and galley. Below deck were six double-bunk rooms and an extra bedroom for any guests who might drop in.

“Sue makes any room our home,” Alan says. She put flowers and magazines around, they tacked up pictures of the children, and one evening Alan, too, contributed to the decor. “About half the company went to a benefit art exhibit on the island. We climbed 400 steps to get there, and when we got to the top the fuse blew. No lights. Everybody was running around with candles trying to see the exhibit.” But it was a benefit, so Alan bought a picture by candlelight.

Social activities were, of necessity, limited. There was no theatre, no restaurant. “We would go from one boat to another for dinner, for a change.” The boats included a summer cruiser used as a floating hotel for most of the company, and the “S. S. Neraida,” formerly owned by Count Ciano, Mussolini’s son-in-law, on which Clifton Webb and his mother lived. once they went up to the monastery at the top of the hill. “The car was about forty years old, and the driver kept turning the gas off and on to save gasoline.”

One gala evening Alan and Sue entertained with a musical clambake at the local tavern. “Alan collected some musicians who played the bazooki, an instrument like a mandolin,” Sue relates. “We walked down the cobblestoned Street, and by the time we got to the tavern we’d picked up fourteen people from the company.” They bought wine for the whole party, had a festive evening, and the tab was only $1.27. “Real sports,” says Sue.

Only one man spoke English in their international crew of nine, which included Italians, Greeks and a Chinese cook named Mike. Mike had been lost at sea off the coast of Greece forty years before. He’d married a Greek woman “and he speaks nothing well now—not even Chinese.”

But Mike could make himself understood when anyone invaded his domain, the galley. One day Alan decided he wanted to make a salad. He chipped up tomatoes, onions, garlic, lettuce. “Just the usual salad, but I wanted to season it the way I like it.” Mike stood watching over Alan’s shoulder while he threw in the spices. Tension was obviously mounting. Suddenly, without a word, Mike wheeled away.

“What’s the matter with Mike?” Alan asked, adding more garlic.

“He’s upset,” the crew member who could speak English explained.

Mike was so upset that he was hanging over the side of the boat, violently ill. In the excitement his false teeth fell into the water and Alan, feeling responsible, gave him the money to replace them. As he adds, “That was the most expensive salad I’ve ever made.”

Mike’s idea of a perfect dinner was fried mashed potatoes for an appetizer, then soup, meat and potatoes. There were no kitchen appliances, no toaster or broiler or even an oven aboard. They made toast by frying it in a pan. When Alan and Sue got too hungry for American food they’d order by radio from the American Air Force base in Athens. “They would send us chicken and steaks. And when we went to Athens we’d stop at the PX at the base and get hamburgers, Cokes, Tabasco sauce, relishes—all those things you miss,” says Sue. Out of experience, Alan and Sue had taken along some portables like pancake mix, which proved a real luxury.

Occasionally Alan and Sue would go quietly into the galley late at night, when Mike was asleep, and prepare Alan’s informal snacks. “Alan likes to eat late, and he’s used to getting it himself—or me getting it,” Sue says. “He won’t ask anybody else. I think that’s one reason he doesn’t like to travel. He likes to be home—where he can raid the ice box.” But take Alan’s word for it, this location trip was tougher on Sue. “No telephone. Sue went out of her mind,” he grins.

“Alan’s the worrier,” Sue retorts. “When we were where they had phones, if I’d called home every time Alan said, ‘Don’t you think you ought to talk to the kids?’ we’d still be over there, working to pay off the phone company!”

Actually, that was the tough one—being separated from their family. Otherwise, as Alan says, “We’ve traveled enough so that we can adjust to about anything. I don’t want to go, but nothing really bothers me after I get there. Sue and I’ve bunked in a trailer on movie locations. The two of us used to sleep in an upper berth on hospital tours.”

As in some measure a substitute for the family, Alan and Sue would talk to little Piero Giagnoni, nine-year-old Italian actor in “Boy on a Dolphin.” They would talk about America, about the kids, about baseball. “We missed David so,” Alan says. “And Piero was a doll. Big brown eyes, sensitive face, such a smart kid. If he needed it, I’d step on Piero, just as I’d step on David. I taught him English, and he learned as rapidly as anybody I’ve ever known. He really wanted to learn.”

One day they had Piero over for lunch, and Sue made pancakes for him. Another night when the company worked late “we put Piero to bed on our boat,” Sue relates. “And I made him say his prayers, not a word of which I understood.” On a night like this, thinking of their own nine-year-old at home, Adan and Sue were about ready to give up the ship.

It was hard not being together with the family on Thanksgiving, for instance. Alan and Sue sat in a hotel room in Athens, looking at each other over an untouched turkey and a bowl of fresh fruit. Saying nothing, lest they say too much. They called home, “and when I heard the kids’ voices I started to cry,” Sue says. When she cried, she triggered them all off. Carol Lee put David on the phone, and when Alan heard his gravel sniffle he choked up and handed the phone back to Sue. Expensive silence, with nobody saying a word.

Missing chapters in the family scrapbook, important family firsts, that can never be relived. Such as not being with David when he saw his first picture, Jaguar Productions’ “The Big Land,” in a Warners projection room. “I don’t think I was very good,” he wrote. “I rode the horse all right. That part was okay. But I don’t think the rest of it’s good.”

Riding the horse had been a big victory for David. He was supposed to ride like the wind, and he had felt hurt when they talked of getting a double for him. Then he was plain humiliated when he found out the double would be a girl.

“Daddy, I can do it. Please let me,” he’d begged.

“David, I can’t take the chance. You might get hurt—”

“No, I wouldn’t. I’ll show you,” he said. With which David had immediately taken off across the pasture, riding like the very wind. He had won his point. And now he thought the riding was “okay.”

Another family first: Carol Lee had sent her parents some new photographs of her thirteen-year-old sister, Lonnie, and the 20th representative in Greece had flipped, saying, “Get a set of these out to the studio in Hollywood. They’re looking for kids like her.” When Carol Lee took Lonnie out to be interviewed, the studio wanted to sign both of them. In no time they were both studying drama with Ben Bard, who’d coached their dad many years before.

An active family, these Ladds, with events happening fast. Too fast when you’re thousands of miles apart. But Alan and Sue have never believed in marital separations, and as long as the children are adequately provided for, Alan wants Sue with him.

“Carol Lee was with the children. She’s even more strict than her mother,” Alan says. “She’s more like I am. Laddie was with them, too, and Johnny Betz, who’s like my own brother, always stays at the house when we’re away. If anything ever happened to those kids Johnny would kill nine people. Friends of ours like the Bendixes, the Demarests and the Eddie O’Briens all had them over for dinner. And we kept in constant touch—”

They heard from Carol Lee almost every day, and all the children wrote fairly often. Sue would write a “family . letter” every day and a personal letter to each of them twice a week. Report cards were sent over faithfully and carefully scrutinized out there in the boat in the Aegean Sea. “If their grades weren’t good enough, we’d clamp down. Cancel all leaves—”

Once a week Alan and Sue made the four-hour boat trip to Athens and called home. Confused phone calls, usually, fading out at about every third word, with the children talking in their sleep. The telephone exchange in Athens did not open until three p.m. With the ten hours difference in time, “we’d just barely hear voices really—sleepy voices. It was especially hard to wake Lonnie in the small hours of the morning,” her mother recalls.

They’d usually call at six p.m., Athens time. As Alan says, “We figured that about four in the morning was the best time to catch them all. David gets up and leaves for school around 7:30. Laddie would be at his fraternity house in the afternoons. Lonnie and Carol Lee would be in and out. At noon, nobody’s there at all. And it’s a bad gamble at five in the afternoon or at eight in the evening. But if we called at four a.m. we knew darn well they’d all be there.”

“Go wake up everybody,” Sue would say. And finally, “Get Lonnie on the phone.” Silence, then, “We’re trying, Mommy,” Carol Lee would say. “She’s coming—I think.”

Sometimes there would be a small crisis to be solved, like the time their walk-in deep freeze had gone off while the kids were at the house in Palm Springs. Three hundred chickens in storage from the ranch had rotted “and melted into the wood.” They were using gas masks and scrubbing with lye, but this wasn’t working. The help was threatening to quit, for their quarters were right over the basement.

“They’re fumigating,” said Carol Lee. But the deep freeze might have to come out.

“How?” her dad said anxiously. “We had to knock down the basement wall to put it in.”

“That’s how it has to come out,” she said.

“Oh, no!” Alan gasped, thousands of miles away. “Don’t do that! Think of something else!”

Six days of waiting brought an airmail letter to explain how it was straightened out, but by then another small crisis had occurred. “My brother Laddie’s car seat had caught fire on the Hollywood Freeway,” Carol Lee recalls. Her brother and a frat friend were driving along the freeway in his convertible, when a passing motorist flipped a cigarette into the back seat. It burst into flame, and they’d had to pull off the freeway and put bushels of dirt on it—

Half a world apart, and there were important little personal decisions to be made, too.

Like Lonnie, belle of the ninth grade, explaining to a good-looking high-school junior that she still can’t go out alone in the car with him. Yes, she knows he takes out older girls who can. “But that’s one of the few things my mother has asked me not to do. And I can’t do it—”

And there was the matter of David being all fired up about taking drumming lessons. “You’ll have to ask Dad next time he calls,” Carol Lee told him. When their parents called that week, she alerted them.

“David, when I was a boy I wanted to play the clarinet,” Alan told him. “But I couldn’t afford it. I’ve always wanted to play one. If you want to study clarinet, now, I’ll see that you get one—”

David, who worships his dad, took up the offer. He was really dedicated to doing Alan proud on the clarinet. As Carol Lee wrote, “David’s teacher says he’s never seen a kid learn so much so soon.” David was determined to learn to play “Onward, Christian Soldiers” for his dad and “Sweet Sue” for his mother by the time they came home. But as that day neared it was all too apparent that “Onward, Christian Soldiers” would be about all he could manage.

For Sue and Alan, remembering the Yugoslav incident, it was almost as tough getting home as it had been getting over there. And their new Jaguar Production, “The Deep Six,” was scheduled to roll—or else.

The sun shines brightly over the Aegean, but all around it there were dark clouds of political crisis. Cyprus was one hour away. Four hours away, the Suez Canal had been seized and Egypt bombed. Travel was tight. Americans and Britons were evacuating the Middle East. Boats and planes and trains were jammed and it was almost impossible to get reservations. The final scene for “Boy on a Dolphin” rolled to an end only just in time for Alan and Sue to keep their reservations aboard the Mauretania.

For once they made a boat—but the boat didn’t make them. At Le Havre there was a big storm and the liner couldn’t get into the harbor. For seven hours Alan and Sue sat in the boat station waiting.

Out in the Atlantic, fog shrouded them in. Alan went up on the bridge and talked to the navigators, passing the time. “Why don’t you move this thing?” he said, looking out at the blanket of pure fog. “You do want to get home, don’t you?” they said. Then they told him. A freighter had just missed them by a coat of paint, right where the Andrea Doria went down—

New York and, true to pattern, pandemonium. They were twenty-four hours late and all train and plane reservations were gone. There was a train at six they might make if they could be whisked through customs. It was four-thirty then. They were whisked—leaving a whole army of bags on the other side of the counter.

“Don’t worry, Mrs. Ladd. It will catch up with you in Chicago,” the porter said.

A rush to Pennsylvania Station, to make the train just in the nick of time. Then, a feeling of relief as they settled down for the long ride. As the speeding train hurtled through the plains and mountains, their spirits soared. The long journey would soon be at an end.

At last, they were home. The house was shining and waiting. Every window carefully washed, every floor lovingly waxed, by their family’s own hot little hands. Wonderfully, the basement wall was still there. The deep freeze was purring away, just as though it hadn’t almost been an international incident. New teen-aged faces, boy friends of Lonnie’s, were flooding the house. And a very proud David brought out a shiny clarinet and played “Onward, Christian Soldiers” straight through, not more than a little off-key.

The phone rings. A well-known producer has been holding a great script for Alan. Great part. Great director. Great budget. In short, great.

“Africa?” repeats Sue weakly.

Four pairs of eyes turn as one. “Africa!”

“Forget it,” says Alan into the phone, in a tone that means “Forget it.” Alan and Sue are home. Home with the heartwarming memory of all those friendly faraway faces. But home. God and the future willing, this is just where they will remain.

But the phone keeps on chattering. “Africa, huh?” says Alan. “Tell me some more about that script—”

THE END

GO SEE: Alan Ladd in 20th Century-Fox’s “Boy on a Dolphin,” and Warners’ “The Deep Six.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1957

AUDIO BOOK