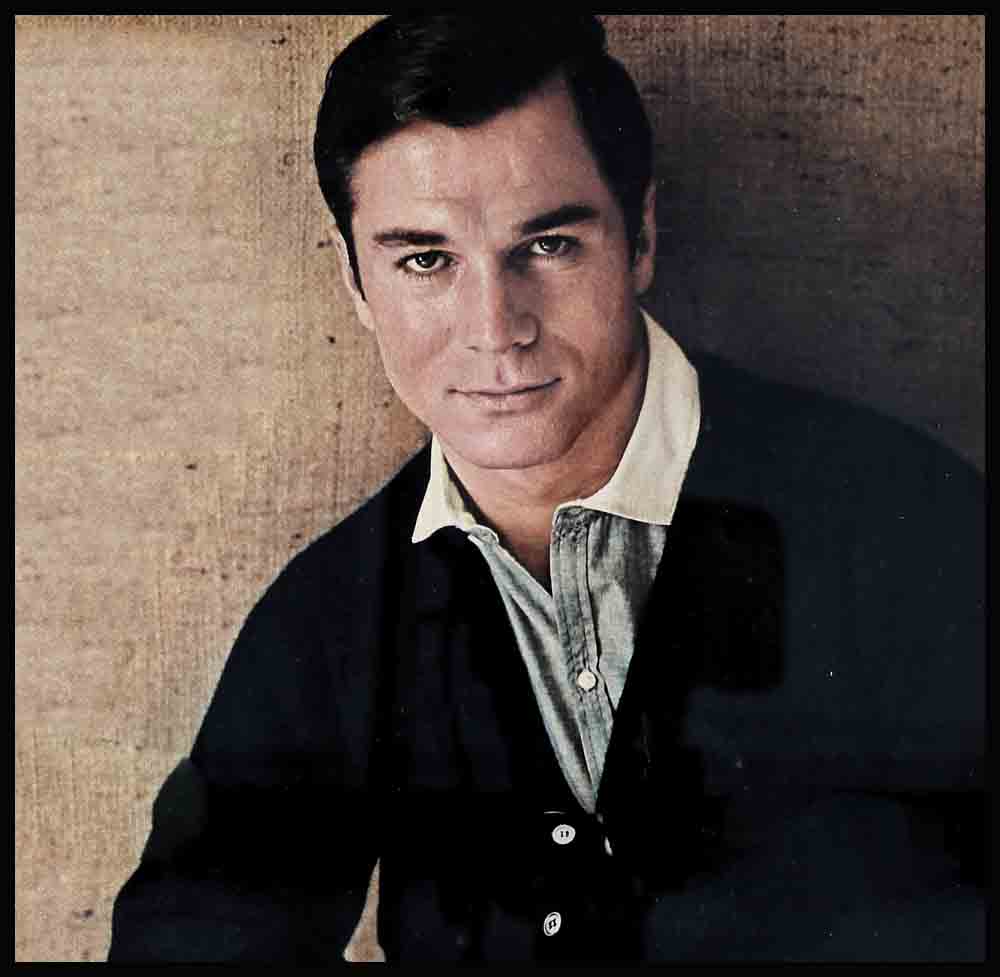

The Guy Who Hates His Past But Won’t Give It Up

Instead, he turns on the lights-all the lights-puts a record on the portable stereo—Ella maybe, or Ray Charles, or Dinah Washington or Brook Benton—and he blasts the record full pitch. He turns on the TV next; bright picture, volume high. He runs into the t bathroom and turns on the water in the sink, in the tub. For good luck and extra measure he flushes the toilet a couple of times: awhooosh, awhoosh . . . nice and loud.

Then he gets into bed and he smiles.

“You see,” he says, “I get wound up when things are too silent. And I get a great satisfaction knowing that everything else is working finally and I’m not. I turn on all these things, these gadgets, and I say, ‘Now you work. I’m going to sleep.’ And I do. It’s a way of breaking routine. I hate routine. all day has been routine for me. Life can become routine, if you don’t watch out. And this, you can say, is a way of helping to break the mold.”

There are many George Maharises.

There’s George the mold-breaker. There’s fun-loving George. There’s generous George, dedicated George. There’s restless George, sensitive George. There’s arrogant George. There’s George the dreamer. There are many different Georges.

Each of them has a story.

To get those stories I made phone calls, paid visits, I traveled about, asked questions and got answers . . . From people who know George Maharis, or knew him when. And from George Maharis himself.

It started in Astoria

I started by visiting the neighbors where he lived as a kid. It’s a Jewish- Italian-Irish-Greek neighborhood in a place called Astoria, in Queens; a ten- minute subway ride from Manhattan. It’s not a fancy neighborhood by any means, though the apartment buildings on Twenty-ninth Street, George’s old Street—the Lady Hamilton, the Lady Patricia, Elm Towers—give you the feeling of a hoped-for graciousness that somehow was never achieved.

The owner of the five-story walkup in which George and his family had lived didn’t even bother to give his building a name. He simply called it by its number: 30-47. I rang a few doorbells at 30-47.

Said one woman, who opened her door slightly, “My Harris? My Harris? I ain’t got no Harris. I only got an Arthur.” And she closed the door, tight.

Said another woman, “Maharis? Sure I remember the Maharises. Lovely people. Quite a long time since they lived here, though. So one of them’s an actor now, huh? Yeah, I’ve seen him on the TV. But you know, for the life of me I can’t tell which one it is. Two of the brothers—they looked just alike. One was a nice kid. One was fresh. I don’t remember the names, but I have a feeling it’s the fresh one who’s making the success. Huh? Isn’t that the way it always is?”

Said a third woman, “Her, she’s always gotta go say something nasty about people. But she’s right. George Maharis, when he was a kid, he was fresh all right. Or maybe odd is the better word. I don’t know. It’s interesting, though, what my son Peter was saying about George just the other night. Peter’s very philosophical. He’s in decorating. Interiors. Anyway, the other night Peter started talking about George, remembering him. And he said, ‘You know, Ma, when George Maharis was a kid I thought he was going to be headed straight for the electric chair’—Godferbit.

“Peter said how there were other kids from this neighborhood who did bad things and got the chair, or twenty years, or thirty years. And George, Peter said, he seemed to be headed along the same road. Not that he ever got in trouble with the police, Godferbit. But he seemed to have a look about him that was trouble- some, like Peter puts it. Troublesome. Except Peter remembers that George had a bravery about him, too. Like for instance the time one winter’s day when he saw George sitting in the playyard of P.S. 5, just down the Street here. And this gang of other boys, snotnoses—excuse the language, but that’s what they were—they came along and told George to get moving, that he was sitting in a spot where they wanted to play.

“George told them, ‘Get moving your- selves. I was here first.’

“So the other boys—to try to make George move—they got icicles that were hanging from the side of the school building. And they began to crack them over George’s head. The icicles. One after the other; big, hard icicles. And Peter remembers that George didn’t budge, that he just sat there till the other boys gave up trying to get him to move. So, like Peter says, George had a troublesomeness about him. But a bravery too. And like he says. he’s glad that the good won out over the bad in George.”

The woman went on to say, “But if you really want to find out about George as a boy, why don’t you talk to Pat. That’s his sister, a terrific girl, a little younger than George. She came by to visit the old neighborhood once, a couple of months ago, and she stopped in to see me and gave me her telephone number. In case I ever wanted to phone her and chat. Here . . . let me find it . . . Come on in . . . it’s in the kitchen here, I think . . . yeah . . . here. Here. Why don’t you copy down the number and give Pat a ring and see what she’s got to say about her famous brother? I’m sure she’s at least proud of him.”

I dialed the number from a candy store down the Street a few minutes later. The line was busy, so I left the store and walked around for a while, past some of the landmarks of George Maharis’ child- hood: P.S. 5, an ancient red-brick building with a small green cupola sitting atop it; the old Roosevelt Theater—affectionately known back then as The Itch—where every kid in the neighborhood went to see the pitchas Saturday afternoons; the church of Atioe Ahmhtpioe, St. Demetrios, the little Greek Orthodox church which the Maharises attended.

I stopped in a shoe repair store for a moment, not far from the church. The store is run by a round, swarthy man named Comitas Lambrosinos.

Did he remember George, I asked.

Lambrosinos’ face broke into an Olympian smile. “Greek boy? On the televisions? Wonderful, no? Sure I remember. Good boy. Good Greek boy. And he make us proud, all the Greeks of America. Good boy. Astoria boy . . . very proud.”

Back at the candy store, I tried Pat’s number again. This time the line was free, she answered, and she told me, “What do I remember best about my brother as a boy? Golly, I guess I could write a book with everything I remember.

. . . You’ve been over to 30-47, our old house? Well, as best as I can recall, we had an apartment there with three bed- rooms and a living room, kitchen and bath- room. George shared a room with our brother Bob. They were very close, George and Bob. always. Even today Bob travels around with George on the show, and they look so much alike that people still get them mixed up. But back then, when they were kids, they looked so much alike that a lot of people took them for twins, especially since my mother dressed them so much alike.

“One funny story I recall is that every time George got into any argument with anybody and won, the kids would be on the lookout for him—and many a time poor Bob was mistaken for him and got the beating. And in Flushing High, where they both attended, they would switch classes and the teachers never knew the difference.

“But about our apartment on Twenty- ninth Street. Every time I think of it I remember a fat lazy boy that lived on the top floor—such a pain in the neck it was a pleasure when George played tricks on him. The fat kid would stand on the side- walk and call out, ‘Mama! Mama.’ And George would run to the window and imitate the mother’s voice.” ‘Yes, Sonny-boy?’ he’d say.

“ ‘Mama,’ the fat boy would ask, ‘can I stay out late tonight?’

“And George would make his voice real high and say, ‘Yes, Sonny-boy, because you’re such a good boy you can stay out as late as you want tonight—even go to the movies if you want.’

“And then a few hours later you’d hear their voices coming from upstairs, above us. The fat boy would be crying and saying: ‘But Mama. Mama, you said it was all right. I heard you with my own ears.’ And the mother would scream: I’ll box your ears if you keep lying to me, that’s what I’ll do with your ears!’

“And George and the rest of us would just sit in our own apartment, listening and laughing and laughing.

“George would even fool my mother. A grocery wagon used to come around at a certain time every day. George would go downstairs and order a whole load of things—fruits and vegetables, especially; he liked health foods as much then as he does now. And when the wagon man walked up all the stairs to deliver the stuff, my mother would say she never ordered any of it, but out of politeness she would pay for it and accept it.

“Later George got punished, of course. This always hurt me very badly. I never liked to see my brother punished. Though I guess he had it coming to him at times.

The girls liked George

“And yet there were times when he couldn’t help it. I mean, he was very good-looking as a boy, and girls in the neighborhood were attracted to him. They had a habit of borrowing his clothes, which they never returned, but kept as souvenirs. And since we were far from a rich family, with no clothes to spare, this used to get my mother annoyed. She’d holler at George about this. But, as I said, this couldn’t exactly be called his fault. And sometimes, believe me, George would holler right back. He always had a short temper, still has. Though he’s learned to control himself better as he gets older. However, he is quick to for- give and forget. And speaking of forgetting, he also forgets birthdays—which is really not a bad fault.

“But I’m getting off the track. I meant to say that George was a lot of fun, those days. And lots of times—when he wasn’t in one of his serious moods—he’d keep us in stitches. At the dinner table he’d do impersonations and clown around and tell jokes. He was a wonderful painter—he still loves to paint—and he’d make funny cartoons of all of us. And he had an amazing imagination for nicknaming people. He used to call me Clee-Clee for Cleopatra, which is my real name. He used to call Gus, our brother, Gousy-Lousy. And our sister Mary he called Maryutch. To get even we called him Georgie-Porgie most of the time, though my parents always called him Yohrgi, which is Greek for George.

“Another thing I remember he used to do—he loved to experiment in baking. Sometimes he’d go in the kitchen and mix up a lot of things and put it all in the oven. And we’d watch it overflow and bubble all over the place. And we’d have to sample it afterwards, reluctantly— though believe it or not it was usually good. One time he took some thyme and cooked it in a frying pan and the smell was so terrible it turned out to be like a laughing gas. Because that’s what we did, we laughed so much we got hysterical.

“But, as I said, George had his more serious moments, too. And thinking back, these are the moments I remember best about him. Like when he listened to the radio. His favorite programs were the “Lone Ranger,” which he called the Long Ranger. And “Mark of Zorro.” And “I Love a Mystery.” He’d listen to these with such concentration that you couldn’t disturb him if you tried.

“ ‘George,’ we’d say.

“ ‘Huh?’ he’d ask.

“ ‘We’re going over to the Williamsburg Bridge—’

“ ‘Uh-huh.’

“ ‘And we’re all gonna jump off and go in the East River for a swim!’

“ ‘Good.’ And he’d wave like he’d heard exactly what we had said, and then he’d go back to listening to his radio program.

“He could be very serious. He could sit there and think and think and think till yon had to go over and ask him what he was thinking about. Usually he was very vague. He’d say, I’m daydreaming, Clee-Clee. Just daydreaming.’

“I was too young to be able to figure what he was daydreaming about. Nobody knew, really. Though I have a hunch my mother knew in her way what was going on in George’s mind. Because once in a while, if I was really disturbing George and his temper would Hare at me, my mother would take me aside and say, ‘Shhhhh, Cleopatra. Leave Yohrgi alone. He’s dreaming of something. He’s the dreamer of the family. There’s nothing wrong with that. Some people must do things. And others must dream before they do things. So leave him be for a little while. And leave him to his dreams.’ ”

A dream of freedom!

“Pat’s right,” George says today. “I was a dreamer. What was my dream? To bust out. To cut loose. To have complete freedom. I always fought for that. It was the greatest trouble between myself and my family. I wanted to breathe. I didn’t want to be told I had to do things a certain way. I’d suggest things, say I wanted to do things. And the answer was always ‘No!’ I’m sure there were reasons. When I was born, when I was small, my father was well off—he had three restaurants. But within a few years there was nothing. Only bill collectors. And strain. And changes. My father had nothing and he had to work harder than ever now—two jobs. My mother had to take a job in bubble gum factory. We were six kids for them to take care of. They didn’t want up to split apart. They were Greeks and Greek means family, and lose that and you lose everything. So the cry became ‘Keep it tight. Keep it close.’ It got close I ended up turning wild. There are blanks in my mind when it comes to certain periods of my life. This is one o them. I can only remember slashing out fighting. I was told a terrible story by someone once. It’s a story I’ve never told anyone before this. I was told that m mother was pregnant once and that made her trip and she had a miscarriage and the new baby died. I’ve asked he about this. But she won’t talk about it. Still To this day. She just says, “ ‘Shhhhhh, we don’t speak about such things.’ And that’ nice of her.

“But from her niceness, I get the picture. The picture of my own wildness those days . . . Well, I broke out eventually. I got my freedom. And I had to pay a price for my freedom. I hated herds? I hated families? I became a loner? I ignored everybody? Well, now everybody ignored me. It was pretty awful. Yet the strange thing is that it gave me kind of resistance that helped me later or—it turned all the minerals inside me into steel—and it developed the energy inside me that I was going to need later on. Need bad . . .

“Does my story have a happy ending? Yes. Yes, it does. I knew after a while that if anything was going to happen, had to come from me. I started to look a them—my family—instead of at myself. realized lots of things, especially that everything they had done, had tried to do was really for my benefit. Because the; loved me.

“And I realized something important about myself. When I was a kid—poor—I thought that if I could have a car, a house, a yacht, an estate—then everybody would know I was as good as they were. But as time passed, I realized I didn’t really want these things. I realized I wanted to be an actor, not a property owner. I wanted to be an artist, not rich And all these things I’d blamed my family for not having given me—I knew now that I hadn’t ever really wanted them at all Possessions—they were a part of my dream yes. But they were not what I was really dreaming about, it turned out. You see what I mean?”

It was still early enough that day, after my talk with Pat, to grab a bus from Astoria for Flushing—another and slightly more prosperous section of Queens—and pay a visit to the high school George once attended.

Flushing High is a huge building, gray-stone Gothic; but there’s nothing archaic-looking about some of the girl students there.

Said a teenage Kim Novak type, whom I approached on the main staircase, “George Maharis? You writing a story on him? You know him? . . . Oh. I thought you knew him personally . . . Oh . . . Well, all I know is that his brother Paul attends here. He’s a doll. Umffffff. That family. I’m telling you. What dolls! . . . No. I’m sorry. I don’t know any of the teachers George had here. I wish I could help you. But say—maybe you could talk to Miss Cooper. She’s been around here a long time. She knows everybody. Maybe she knew George.”

Miss Cooper, a pleasant lady, told me a few minutes later that no, unfortunately, she didn’t know George Maharis. “In fact, he attended quite a few years ago and there’s been quite a turnover here among teachers. So I doubt you’ll find any teacher here who remembers.”

But she made a suggestion. Why not get in touch with another alumnus—one Jerry Bock. He’s a composer, Miss Cooper says, author of such hit musicals as “Fiorello!,” “Tenderloin,” “Mr. Wonderful.” He and George attended Flushing High at the same time, the teacher says. In fact—and this she definitely recalls—it was back in the late 1940s, when they were both students here, that Jerry wrote a musical, “My Dream,” in which George starred.

An old school friend

I finally located Jerry Bock at his home in New Rochelle, a fashionable New York City suburb. He said laughing. “Well. how do you like this? Just this morning I went out and bought a copy of George’s new album (Editor’s Note: “George Maharis Sings”). I just finished listening to it. Do you know the album? Hasn’t he got a great voice? I knew this years back about George, when we did ‘My Dream.’ It was a simple little musical. High school stuff; a high school love story. It was supposed to run one night but it ran two. Or was it three? Anyway, part of its success was due to George. He had the male lead. He sang three songs. And he sang them beautifully. It’s funny, but I always wanted to keep this phase of his abilities a secret. Until I could write something for him—a musical—something for Broadway. So what happens? The secret’s out now. He’s on records. Well, maybe someday—if he’s available, or interested—maybe we can still get together on something again. I’d be very pleased. I’d cast him in a musical any time. He has a very good voice—popular and theatrical. I think his musical ability, added to his acting ability, should make him one of the hottest properties in the business before too long.

“Yes, George and I were friends in school. Although I think you can say that working on the show brought us as close together as we ever got. I think we both got involved in school politics, too, for a while. It’s been a number of years now, and I forget. Unhappily, we haven’t seen each other more than once since graduation. That was when George did ‘Zoo Story’ off-Broadway. I thought he was just marvelous in that. As did the critics.

“What key word would I apply to George, the George I knew? Well, going back—and remember, this is all rummaging through my vague memory—I would say that he runs deeper than he looks. He’s smarter than he appears to be, much smarter. And a very nice guy, though he sometimes gave some people the impression that he was not. And—of course, this may be hindsight and nothing more—but I’d say about him, too, that he seemed to always have a kind of purposeful dedication. You sensed that he wanted to do something in life and that, no matter what, he would take a straight path and do whatever he wanted to do. So I’d say he was dedicated. Very dedicated. And, as he has proven, to great purpose.”

Says George, hearing about the phone talk with his old friend, “Jerry’s a charmer, isn’t he? And I was charming in high school. too. I was the big political boss, the behind-the-scenes man. I didn’t want to run for anything. Who needed that? But I was the one who picked the kids who did run—and who won. I didn’t bother with the seniors, the big intellectuals. I’d say: ‘What good are they? They’ll be out of school in six months, and what good will they do the school?’

“Instead, I’d concentrate on the younger kids, the freshmen and sophomores. I’d talk to them. I’d see which of them was really smart, interested in school affairs, in getting something done for the other kids. And then, when I was impressed with them, I’d stand behind them. Like a campaign manager. I was a good one, too. Very hotsy-totsy. Although I’ve got to admit some of the kids didn’t like this manipulating of mine and used to call me The Dictator. … I was charming in school. Charming. And I had some charming teachers. A lot of them had crushes on me. And why not? There’s nothing unusual in that between a teacher and a student. There was one—my faculty advisor. Miss Carmen. She was warm, understanding, gray hair, no makeup, smiling eyes. You knew that you could tell her something and that she would understand. You knew that she demanded the truth, but that everything you told her was in confidence. You knew, most important, that she would be an equal when you talked to her. and not a superior. Another teacher—I forget her name—always gave the impression of being a battle-ax. She had cross eyes, pocky skin—she was really something to see. She always frowned at me and gave me a hard time. But I always felt she cared for me. And she did. She proved it when she’d get mad at me, when she’d take me down a peg or two. Whenever she felt my popularity was going to my head, she’d take me aside and bawl me out. But rough as her voice was, and cross-eyed as she was, she did it all with a certain inner tenderness. And I had the feeling it was for me that she was bawling me out. And this was a very nice feeling. Then there was this history teacher; this one really had a crush on me, I felt. She was a very unusual-looking woman. Like a point, she was. She had long thin legs—not skinny—that came to a—point! When she walked her feet went toe for- ward—point! When she spoke, the words seemed to hit you like little—points! She was pointedly delicate, let’s say. She used to write me little notes of encouragement. As popular as I was in that school. it was a fact that I never smiled. And she’d write to me. ‘You have a million-dollar smile, George. Please try to let us see your teeth more often.’

“Like Jerry Bock said it to you on the phone, she used to say it to me, too, back then. About the dedication, I mean. She used to say, ‘I think you’re headed for something big, George. Point! But do you know where it is you’re going? Point! Point!’

“And I’d say, ‘Not really, except I feel absolutely sure I am going someplace.’

“ ‘But,’ she’d say, ‘you’re so disorganized in your thinking, George. Just the fact that you don’t know where you’re going proves that.’

“And I’d say to her; ‘I don’t think dedication has to be something rigid or organized. I think it has to be like a weathervane, that turns with the wind. A weathervane has an arrow, and an arrow has a direction. But that arrow doesn’t always have to be pointing in the same direction.’

“I’m like that today. I’m dedicated. But I sway like crazy. Like with the wind. Like when I play a certain role. I’ll break any rule or convention to get to the real heart of that role. I don’t hold that anything stands forever. I feel we’re like tool boxes. We need all our facilities, in other words. You don’t use a saw to hammer nails, is what I mean. I’m kind of like nature, too. Sometimes the sun shines in me and sometimes there’s a storm inside of me. A lot of people call this erratic. But I call it the truth of me. I’ve got a very organized disorganization. Like Michelangelo when he made the Moses—it was too perfect, and so he cracked the foot. He didn’t want his statue to be too perfect. Because he knew that nothing in life is perfect. Like people. Like me.”

George the juice boy

The Salad Bowl is a health food shop on Seventh Avenue, smack in the heart of New York City’s big-time show biz district. George worked here as a juice boy once—six or seven years ago, after his graduation from high school and after a two-year stint in the Marines. Sid and Mel, the Salad Bowl hosts, remember him. “One of the best juicers we ever had. Quick. Could take a couple of carrots, toss them in the machine, squeeze—and presto, ‘Here’s your glass of health.’ That’s what George used to say. . . . Big success on television now, eh? Well, good for him. But if he ever gets tired of it all, that ‘Route 66’ stuff. that Hollywood life, and wants a job as juice boy again—tell him we’ve always got an opening.”

They laugh. A woman walks into the Salad Bowl—a thin woman, with long blond hair, about forty—maybe a little more—with what can best be described as a Broadway face: a little weary, a lot wise.

“What’s so funny?” she asks, hearing the laughter. Sid and Mel tell her they’ve just been reminiscing about George Maharis. She smiles. Her name is Irene—she’s a part-time newspaperwoman, she says, “and sister-in-law to the greatest horse race handicapper of them all.

“I’ll tell you about George Maharis,” she says. “I worked here the same time he did. Right, fellows? Well, not really worked here. You might say Irene was helping out her friends. Right, fellows? But George. Let me tell you about George. Now there was a grand fellow. With a marvelous personality. Everybody’s pal, he was. Very sincere. A grand fellow. One of the nicest fellows. Back then he was working his way through singing lessons. He never talked about being an actor, either, all he used to say was, ‘Someday I’m going to be a singer, Irene.’ And he sweated it out plenty to make the dough for his lessons. He worked hard here. Long hours. Six days a week. But never complaining . . .

“He was a tease. George was. And fun? He could make a day of work go like this for you just because he was so much fun to be around. All the customers loved his smile. He’d have that lovely smile that would send you feeling good from the top of your head to the tippy-tip of your toes.

. . . I was crazy about him. And so were the customers. They get a lot of entertainment people in this place, you know. Now. Then. Back then I remember we used to get Red Buttons, Berle, Dick Shawn, Jan Peerce of the opera, sometimes even Perry Como used to come in with—what’s his name—the bandleader—Mitch Ayres? Yeah, they all used to come in. And they loved George.

“But you know what? George never once took advantage of the fact that they were here and that he wanted to get into show business. He never once said to them. ‘Would you like to hear me sing sometime?’ Or, ‘Is there anything you might be able to do for me?’ Not George. To him, they were the customers and he was the juice boy. And that was it. Anyway, George always gave the impression that anything he was going to amount to was going to be done on his own, and that he didn’t need or want help from anybody. In fact, in those days we used to have tables up on the balcony, back there. And sometimes the celebrities would come in and I’d say to George, ‘You go up there, George, instead of me. Won’t hurt you to say hello to some of the big-timers. Leave me to take care of the small-timers here at the counter.’ And George would say, ‘Never mind, Irene. You do your job and I’ll do mine.’ Just like that. He never took advantage.

“Anyway, George liked girls. And lots of cute girls used to come in for some juice and sit at the counter. And I think he had more fun serving them and talking to them than he would have had going up to any big-shots and trying to make an impression on them. George liked the girls, all right. And they were crazy about him. And about that motorcycle of his, on which he used to take them for a ride sometimes … Is George married yet, I wonder? No, huh? You know, I’ve often thought about that—and yet it doesn’t surprise me, that George isn’t married. I don’t believe he’ll ever be. My feeling is that nothing interests him as much as his work. He’ll be friendly with a girl, he’ll like her a lot, he’ll take her on his motorcycle anytime. But I wouldn’t be surprised if he never got married . . . Poor girl. I mean. the one that almost lands him but doesn’t. She’ll be missing out on such a good boy. And on so much fun.”

Says George, hearing about this talk. “You met Irene? isn’t that a nice woman —and a great face? Fun? Yes, we had a lot of fun those days. I love to tease women, you see. I tell them big lies. If I know a woman is interested in me, I’ll tell her; ‘Say, did you know? I just got married!’ Or if I know a woman is trying to lose weight, I’ll say to her, ‘Boy.’

“ ‘Boy what?’ she’ll ask.

“ ‘Boy, you’re really getting fat!’

“I do it with my mother. all the time. Her name is Demetra, a good beautiful Greek name. For some reason. my brother Bob has started calling her Jane now—like all of a sudden she never heard of Athens and she’s very American. So when I phone her, I always say, “ ‘Hello, is this Jane?’

“And Mama says: ‘Come on, Yohrgi. I know it’s you and that you’re teasing me.’ And she laughs, she gets a big kick out of that . . . I even tease my mother about sex. She’s a very old-fashioned woman, a real sweet woman. And she likes to think that all of her kids were immaculate conceptions. I start teasing her about that, and wow—you should see her leave the room fast . . . Say. One thing. About Irene—did she mention anything about Mary? Mary Vegh? She was a girl I knew back then. She was a ballerina. A little girl who could fit right into my armpit, she was that small. I remember her as a beautiful bird with a broken wing. I felt she was going to die on me any minute, she was that frail. She was a dancer, but she didn’t have the strength for it. She’d dance, dance beautifully, but after a while she’d tire, and she couldn’t seem to keep it up. She was a beautiful girl. I guess you could say I loved her and she felt the same about me. We talked about marriage after a while. But we had a big religious problem. So we split up in time. It wasn’t easy, but that’s what we had to do. Well, Mary’s married now. She has kids. I hadn’t heard from her in years.

“But one day a couple of months back. on location in Texas, a relative of hers came up to me and he introduced himself and he said. ‘George, I’ve got a store here in town and I’d like it if you could come over and do a little personal appearance for me. You know, attract some more customers.’ He said it politely enough. But there was a tone in his voice that I didn’t like—as if he was expecting me to do this because, after all, I’d known Mary once and I owed it to her and to him and to everybody in the family. That’s the night I heard from Mary, after all these years. Somehow, she’d gotten wind of what was up and she called me long-distance to say, ‘Please don’t feel obligated, George, just because this person is a relative of mine.’

“And—maybe I can’t tell you exactly why—but it made me feel very good getting that call from Mary. And being reminded of the girl I’d loved once, and being reminded of one of the reasons why I’d loved her. . . . Will I probably never get married. like Irene says? Who knows? It would be stupid of me to tell you yes or no today. Every day brings changes. Every day brings a new face, a new heart. To- morrow comes—and who knows? But one thing I’ll tell you. I feel one very strong thing about love. Love shouldn’t be a twisting of personalities, a suffocation. It shouldn’t be a crutch, either. Or a hanging-on for dear life. Or an escape. Or a protection. Or a small room where two people crouch together, their eyes closed, protecting one another from the fears out-side. Instead, I feel love should be an advancement. A growing. A big room, a gigantic room, with plenty of breathing space for two people, with a couch so they can sit together when they want, and with lots of easy chairs scattered around the place so they can sit alone whenever they feel that that’s how they want to be for the time being.

“What led me to start talking like this, anyhow? Oh. Yes. Right. The Salad Bowl. Irene. Yes. Those were fun days. I knew Mary then. Other nice people. It was fun. Yes. But those were the un-fun days for me, too. I mean with my career. Irene’s right. I wanted to be a singer then. And I had a good voice. But I went to this bum of a teacher who ruined it on me. And then everything started happening with my ; throat, my voice . . . I remember one wet, chilly wintry day when I caught a cold and my tonsils swelled up. I walked to a clinic and after a couple of days in the clinic the tonsils were removed. And the clinic released me, and it was another bitter day. I didn’t have an overcoat and I was freezing as I made my way back home, back to West Forty-ninth Street, where I lived. I was wearing an old beat-up corduroy jacket, and I had a scarf wrapped around my throat. For some reason, I must have looked suspicious. At any rate, a cop stopped me and began questioning me. I could hardly talk and my throat ached, but I couldn’t persuade this cop to leave me alone. Finally, I lost my temper, something that doesn’t take me too long to do anyhow, and I started shouting at this cop. I guess he was just about to so something drastic, but he stopped short all of a sudden and he looked at me strangely. That’s when I realized what was happening—that I was spraying him with blood that was gushing from my throat. . . . Oh yes. Those were the fun days. Most of them. Most of them. But not all of them. No, sir.”

The end of the world

Forty-ninth Street is like many of Manhattan’s midtown streets. It starts good and ends bad. Get on the crosstown bus on the East Side, for instance. Give the man your fifteen cents, and you travel for a while through the Sutton Place and Turtle Bay areas, two of the poshest neighbor-hoods in the world. Town houses. Terraced apartments. Gold-braided doormen. Tiny and expensive bistros. The very air is perfumed with money.

Then you cross Park Avenue, and Madison Avenue, and Fifth and you enter the commercial area for a while—still pretty glossy. You still smell the money.

Next you reach Seventh Avenue, and Broadway, and you’re in the world of theaters, movie palaces, hot dog stands, overnight pizzerias—with their individual smells of neon and garlic and mustard and sauce-somewhat-marinara.

A little further west you pass by Madison Square Garden. Smell the sweat? The sawdust? The salted tears of the losers? The hot hysterical breathings of the winners?

And then you reach the way-West Side and what you’re liable to smell here is anybody’s guess. To get to the place where George lived (in fact, he still maintains his apartment, so that he can paint—when he’s in New York, and has the time) you get off the bus at Tenth Avenue and walk towards Eleventh.

It’s a long block. and a dismal one. Ahead you can see the Hudson River and the shoulders of two Cunard Line piers, that stand like double pillars of Hercules, signifying the end of the world. And, in a way, you are at the end of the world now. For West Forty-ninth Street is gloomy and depressing and very few people have come here to live or to stand for a while with any high hope of—as George might say—cutting lose, or breaking out.

You pass a hobo in a doorway, a harmless old man. Sleeping it off. Another man, a younger man, opens the door behind him and yells out, “Hey you, get over to Forty-eighth Street. I’m F.B.I.” And the hobo opens his eyes and shrugs, and he begins to rise and to move away.

You pass a couple of kids playing—a boy with a dirty ball, a girl with a two- year-old hula hoop. “Hey, Mister,” they call out at you, “—what do you want here with your pencil and your paper?” You say to them. “Just looking.” And they laugh. The kids. They say, “Looking for what? Around here? You crazy, man? Around here?” Because they know.

Finally. you come to the building where George once lived—where he now paints. You enter the building through a semi-courtyard, just off the Street, and—like they say in all the novels you’ve read about slums—you walk past the garbage pails and enter the darkened hallway and the only thing you can see is the stairwell ahead and a belligerent little sign that reads, “You keep this place clean!”

You don’t ring doorbells in this building, because there aren’t any. Instead, you knock on doors. You knock on one door.

“Did you—do you—know George Maharis?” you ask the man who opens the door.

“No,” says the man. “I don’t know anybody. And about George Maharis—needless to say. he isn’t here much anymore, now that he’s so loaded with caaaaaash.”

You knock on another door. You know somebody’s home here, because you can hear the rock ‘n roll playing on the radio inside. Then you hear it—the sound of ladies’ slippers shuffling toward the door. Then you see it—the outline of an eye, in a crack in the door. And then you hear it again—the sound of ladies’ slippers walking back to where they d come from.

You knock on a few more doors; more strange answers, or no answers.

And then. finally, you find two people in the building who know George—one who knows him vaguely (an old Polish lady who speaks little English, a Mrs. Drobny or Drobnya) ; the other who knows George very well (a young and struggling actor, John Pearce, a tall boy from the South).

The old Polish lady tells you, smiling at first, then smiling less and less, “Of course. Shoo. I remember. When he used live here all the time. Dark boy. With shiny face. Like olive. Like strong healthy olive. No. I don’t talk to him too much. He always running up the stair, or running down . . . to go some place. But I feel I know him. Because I have son like him. Who always run, too. Who can’t stay in same place. What the word for this? Rest-less?”

“I see this in Greek boy. Mr. Maharis. In his eye. The way I used see it in my own son. I see it in Greek boy one night when it is hot and I go for walk. Near river. Down Street. I go for walk, just for the air. And he hot. too—and he go walking, too. You know the pier? Down Street? Well, there was big ship going out this night. French ship, English ship—I don’t know. But all the lights are on it. And you can see the people wave and laugh. The big ship begin to move. I just watch it. I think, ‘Well. there go a big ship some- place.’ But Mr. Maharis—he come along then, to near where I stand. He say hello to me. And then without more word, he begin to watch ship too. And while he watch I look in his eye and I see it, just like I used see it in my son. The eyes, they get nervous. The breathing, it get nervous. The body, it get stiff. And all about him is this feel of the rest-less. Very rest-less. Just like I used to see it in my son. Who go away ten years. Who go away and never write his mother. Never come back. Ten years. Long time. For a mother. Who wait. Who wait. . . .”

John Pearce tells you a few minutes later, “George is my friend. My very good friend. And he’s the most generous friend in the world. I’m an actor. At least I’m trying to be. I haven’t had many breaks yet. As George explains it—and I think he’s right—my time won’t come for a few years yet because I’m the character actor-type and still too young to break into anything. So things are tough from time to time. And whenever they are, George is always there to help me. Although I shouldn’t say always. once, when things were so bad for me, I had to leave my apartment here and room with George next door. I appreciated this. But I guess it also did a little something to my vanity. I guess it hurt me. Whatever it was, I began to act a little cocky. Worse, I began to become a little bit too dependent on George. He told me I’d better watch my step, that dependency wasn’t going to get me anywhere. I tried. But it didn’t work. So George just told me one day that I’d have to get out, leave. And I did. And it hurt me for a while. Until I realized that George was right. That he was still a very generous person. That by asking me to leave and go fend for myself, he was helping me more than if he’d said, ‘Okay, you can stay here and keep depending on me and keep sitting back and keep waiting for somebody else to do for you what you’ve really got to do for yourself. . . .’ ”

Says George, about my visit to Forty- ninth Street, about the words restless, generous: “Yes. I guess they both apply to me. Restless certainly does. You know Janice Rule? Beautiful girl. Beautiful actress. I think Janice put her finger on it better than anybody once. We were working together, in New Orleans. We went to dinner one night, the waiter came over and I snapped out the order. When the food came I gulped it down—fast, fast. When the dinner was over Janice lit a cigarette, sat back and said to me, ‘You know, George, you eat like you’ve just stopped at a service station, ordered ten gallons of gasoline, and then you drive off again.’

“And she’s right—I’m constantly restless. I hate wasted time. This hepatitis of mine is a great waste of time. Everything about it. At the hospital, that first time, they wanted me to stay in bed all the time. They wanted me to use a bed pan. I couldn’t. I’d get up and go. They’d ask me. ‘Well—where’s the bed pan?’

“I’d say, ‘The other nurse took it.’

“They got wise to me three weeks later. I But then it was too late. I could get up and go anytime I wanted by then. It’s like when I was a kid. I went swimming once. I started to drown. But I didn’t call out for help. I figured if I can’t help myself, then there’s no sense in living. And so I helped myself.

“Sometimes, of course, I can get too restless. One reason I didn’t become a success-ful singer a few years ago, for instance. It’s because I tried too hard. Sure that bum teacher I had for a while ruined my voice. But / was trying too hard, too. I was trying to kili a mosquito with a 20,000-pound hammer. It was unnecessary.

“You keep going . . .”

“But most of my restlessness is necessary. Once I remember, I was going to Boston on my motorcycle and I hit a little hump in the road. And flipped over. Well I got right up and on that bike again. And while I was driving away I looked back. And I thought, ‘This motorcycle is like life. If it throws you and you don’t get back on, then that’s where you stay, where you’ve fallen; you’ve found your level and you stay there. So maybe you open a restaurant across the Street from where you fell. Maybe you ask for a job in that hardware store on the other side of the Street. Or else you remain restless and you get back on your motorcycle and you keep your head and you stay cool—and that’s when you really get over the hump in the road.’

“Well, that takes care of restlessness.

. . . Generous? Me? Yes, I guess so. I like to give people things. Not gifts from the store. I can’t stomach that. But I’ll give money. Or certificates. Anything that doesn’t take me too much time. Also, I’ve paid for two people to go to psychiatrists. I think this is important for some people, who need that kind of help and can’t afford it. I was sending a girl I know to a psychiatrist. Till recently. She had terrible problems. She felt that the whole world was I ignoring her, that nobody knew she was alive. She was in desperate shape and used to come to me for help. advice. But with me on the road so much, I could only do so much talking to her. So I sent her to a psychiatrist. I thought things were going well for her. But obviously one night things went very bad for her. And in her desperation. that night, she killed herself. As if to let the world know that she had been alive, at least for one moment—to let the doctor who would come know, the ambulance men, the cops, to let them all know that she had been alive.

“Of course, you’ve got to draw a line to your generosity, too, I’ve found out. Like with my kid brother Paul. Now there’s a great kid for you. He wants to be an actor someday, too. In fact, he’s waiting for them to put me out into pasture because, as he says, ‘I don’t think there can be two actors in the same family.’ Anyway, Paul naturally likes it when I’m generous with him. But enough’s enough, I say. Like the time he phoned my sister Pat and he said to her—he talks like this, very low—he said, ‘Hey, Pat, how would you like a car for Saturdays and Sundays?’

“ ‘Sure,’ Pat said. ‘But how are we going to get one?’

“‘Easy,’ Paul said, ‘I’ll just phone George in California and ask him if he’ll buy me one. I’ll use it Monday through Friday, and you can have it weekends.’

“So Paul calls me. ‘George,’ he says, ‘I got an idea.’

“ ‘Shoot,’ I say.

“ ‘It’s a favor—’ Paul says.

“‘You sure you won’t get mad if I ask rj you?’ Paul says.

“ ‘What is it? What is it?’ I say.

“ ‘Well,’ Paul says, ‘I was thinking that maybe, since you’re my brother, you’d buy me a car.’

“ ‘Uh-huh,’ I say. ‘And what do you have in mind? A Corvette, like mine?’

“ ‘No,’ Paul says.

“ ‘A Ferrari, maybe,’ I say.

“ ‘No,’ Paul says. ‘As a matter of fact, I was thinking more in terms of an XKE Jag.’

“ ‘That’s like in Jaguar?’ I say.

“ ‘Right,’ Paul says.

“ ‘I see,’ I say.

“ ‘Well?’ Paul asks.

“ ‘No,’ I say.

“ ‘But George,’ Paul says, 7 was planning on buying the gas for it, and paying for the insurance.’

“ ‘Don’t do me any favors,’ I say.

“And then I give my kid brother the lecture. The same kind of thing I had to tell my friend Johnny Pearce that other day. About not getting too dependent on anybody. About thinking of how you’re going to do things for yourself. All that jazz, in other words. But important jazz. Because swell as it is to be generous and to appreciate other people’s generosity—what’s the good of this whole thing called our existence if we can’t learn how to help ourselves once in a while? Even if it’s the harder way of getting things done.”

Mimi Weber is a beautiful young woman. Who also happens to be George Maharis’ personal manager and a business associate (they have formed a company called Geomi Productions Ltd., planning on independently producing motion pictures and TV specials). And who happens to know more about George than anyone else around.

I talked to her over lunch one day recently. A few days earlier, she’d been released from the hospital, following serious neck and throat surgery. And though she spoke slowly now, a little hoarsely now, she spoke with the kind of love and frankness and insight that one rarely gets from a person in her profession.

She spoke of how they first met. “It was summer of 1958. I was a production secretary at MCA. One Monday that July I had to go to the makeup room at the NBC Brooklyn studio with a contract for a George Maharis. I walked over to him and introduced myself. What impressed me most about him that first time? He had the wildest eyes. And a beautiful speaking voice. He smiled—that kind of smile that knocks you out for a minute. And then he signed the contract. He told me several years later, when we got to know one another better, that he’d felt a kind of magnetism about me that first time—a feeling that we had something in common—but that he didn’t know what to do about it. Anyway, he said, he knew I was married. Consequently there wasn’t much he could do about it. The important thing is we met, we liked one another and became good friends. And that’s the way it’s been ever since . . . A couple of years intervened. George did ‘Deathwatch’ and ‘Zoo Story’ off-Broadway and received rave notices— which consequently got him his ‘Route 66’ contract. I had gone up in my own job, to an executive position. But always, no matter where George was, he kept in touch—postcards, a letter from Israel, phone calls.”

She spoke about how they both left MCA. “George got kind of disgusted with certain situations that existed. So he left and went with the William Morris Agency. They managed to keep him busy and finally got him a deal to appear in ‘Exodus,’ for Otto Preminger, in which George had a small part that was made into a bigger and bigger part by the time Preminger got through with him. Me? I was fired from MCA, in September of 1961. An event which rocked me and shocked not only some of MCA’s top brass, but some of the top people in the industry who were good friends of mine. But don’t let’s go into that. It’s the best thing that ever happened to me. At least, it got me started on my own. And George was behind me all the way. He’d say to me, very tenderly: ‘Don’t you worry, Mimi. Everything’s going to be okay. I’m going to be behind you in anything you do.’ ”

She spoke about how they continued to keep in touch after that, and how she got to know George more and more, all kinds of little things about him. “Like he’s no phony. When he walks into a room, no matter where he is—it’s the people he’s with who get his attention. He doesn’t look to see who’s looking at him, to see who he can spot. He’s not a table-hopper, not rude. Every once in a while he may go off into his own little world and not be with you, but he snaps out of it fast. And if he doesn’t, well, you just know that that’s George for now, and that’s the way it’s got to be. You just leave him alone to meditate.

. . . He’s very direct. If he likes you, he likes you—and if he doesn’t, well, that’s it for you as far as he’s concerned. . . . George is a fantastic eater and a pleasure to cook for. I would invite him over for dinner from time to time and he’d do justice to anything I made. He loves Italian food, shell macaroni with tomato sauce especially. And roast duck. And spare ribs. His sister gave me a recipe for yogurt ice-box pie. And he’s a big salad man, with all the greens you can think of. And when he eats apples, which are his favorite, and oranges and lemons, he eats them—I mean, skin and all. . . . Most people don’t know that George has a great compassion. He’s a softie. And an unashamed one. He’ll cry in sad movies. He’ll cry when something awful happens to someone else. His face gets a certain expression which is unexplainable. And he gets flushed. He becomes tremendously sad. . . . He’s not the kind of guy who keeps his hand in his pocket. Even back then, when he didn’t have much, we’d go to a restaurant once in a while and he’d overtip the waitress. I’d say, ‘George, what do you want the girl to do? Have a heart attack?’ Now we have a game about tipping and overtipping. But then, it was just his way. There wasn’t much changing him. And I wouldn’t want to. . . . He’s tremendously honest. He doesn’t lust or envy. He appreciates talent in other people. And he is never jealous. Never.”

Going back again, she spoke of the summer of 1961. “I’d been legally separated by now. I’d been fired from my job. I was violently ill that summer. George was in his second year of ‘Route 66’ by now. He was up in Gloucester, Massachusetts, filming on location. I phoned him immediately after I was fired, crying hysterically on the phone. In a matter of minutes he soothed me and even had me laughing. He said: ‘Look, baby. We’re in a fabulous place. Big house. Right on top of the water. Lots of sunshine. So bring your shorts and slacks and come on up right away.’

“I took George up on the invitation. I made a reservation and I took a plane for Boston. George met me at the airport. He drove me back to the house. It was a wonderful place. Lots of wonderful people connected with the show were staying there. And I stayed for a week or so. And in that week, George—just by being the sweet, understanding warm guy that he is—saved me from cracking. And talking with him one day about my future plans, I mentioned something about maybe going into personal management. George said he thought it was a great idea—and that if I did, he’d consider our forming a business association. Which is what has come to happen. Happily. Since that week up in Gloucester.

“George gave my life a meaning. But what’s even more wonderful is that he feels that I’m doing something even greater for him. And he helped my son, too. Neil. Most of Neil’s life, and especially after the breakup in 1961, he lacked so for adult male association and affection and identification. But all he had to do was to meet George Maharis and he knew he’d never have to lack for it again. I don’t know where to start telling you the things George has done for my son. Or how. I’ll tell you one thing, though—it isn’t by any namby-pambying. George doesn’t go for that. In fact, George will kick Neil around—verbally, that is. When George and I renewed our relationship in the summer of ’61, he attended Neil’s Junior High School graduation party. In the months that ensued they became buddies and then, because Neil feels I’m too young a woman to understand men’s problems—he calls me Child Bride—George gave him the privilege of calling anytime it is necessary, collect, no matter where he is, to discuss his problems man to man. This has given Neil great security, and he has never abused the privilege. . . . Yes, they like one another so much. And George keeps after Neil. Like the time Neil was afraid to take a special examination for a certain high school he wanted to go to. George asked him why he was afraid. Neil said, T don’t know. I’m just scared to try.’ He lacked confidence, but had great talent.

“ ‘Well,5 George said, ‘if that’s the way you’re going to be—don’t you come near me anymore. I don’t want to hear the word can’t from you. You can do anything if you really want to.’

“And you can guess what happened, can’t you? Neil took the examination. And passed it. And he’s a very good student in that school today. George also checks up on his work. Everytime he gets into New York, Neil has to show what he’s accomplished.

“No, George never namby-pambied Neil. Although I shouldn’t say that, not really. Because young boys—like everyone else— need softness sometimes. And George would see to it from time to time when he was around that Neil got it. I remember one night, early, we were sitting in my apartment—George, Neil, I—and Myrna Loy, who is a dear friend and whom I also represent. We were talking about current events. I was sitting on the couch with Myrna. And George was in another chair, with Neil on the floor next to him. They were kidding around and I watched as George tousled Neil’s hair and patted his shoulder affectionately and I knew that Neil—that moment—felt the true comradeship and friendship, the acceptance and approval, that he got from George.

“Another time, I remember, Neil was going out on a date to the theater, a very important date with a lovely girl he’d just met. George happened to be at the apartment that night, and just before Neil left George said to him, ‘How much you got on you?’

“ ‘Five dollars,’ Neil said.

“George reached into his pocket and said, ‘Give me the five; here’s ten. I don’t want you to get stuck in case you and your girl want to have a soda after the show.’

“Another time, I remember—but oh, there are so many times I could tell you about. And all I really mean to say is that there’s no more sensitive, no more compassionate, no greater guy on this earth than George. My feelings for him are very special. And I know his are the same for me.

“You know—this operation I just had? It was a tumor, in my neck. Thank God, it turned out to be benign. But about the tumor—obviously it had been there a long time, but it had always been so small even I never noticed it there. And one night—we were going out and I put on a special dress for George. I asked him if he liked the dress—and completely oblivious to my question, he asked, ‘Mimi, what’s that on your neck? It’s swollen.’ ”

“‘Where?’I asked.

“ ‘There,’ he said. And he made me feel it. And it was there all right. And then he made me go to a doctor. And do you know what the doctor said to me? He said, ‘Yes, Miss Weber, it’s a tumor all right. I wish you’d come to me earlier about this.’ And I told him the truth, that I hadn’t noticed it before, that someone else—a man I knew—had.

“And the doctor said to me, ‘Yes. It could be unnoticeable. But—whoever did notice it—he must care for you very, very much.’

“I guess that’s it from me. I guess I’ve told yon everything about George that I can think of right now. Except—there really is so much to be said—things which would be difficult to put into words, no matter how eloquent one could be. He’s a rare man. And a most specially gifted one. I’m so very proud of him. The road upward wasn’t easy for him. You’ll never know.”

I wanted, lastly, to talk to someone—an actor or a director—who had worked with George fairly recently. I contacted a director. And I felt, after talking to him, that maybe I’d contacted the wrong man.

“Maharis?” he’d said. “Maharis is arrogant. That’s all I’m going to tell you about Maharis!”

But the following day—November 30, 1962—I read the following article in the New York Post. And got the picture as to why the director was so sore:

“George Maharis has been suffering from hepatitis since last May. Despite recurrent bouts with illness, he has continued to tape the show. . . . But now the Flushing-born ex-Marine has pulled his super sports-car off the road and cancelled all appearances on the high-rated ‘Route 66’ ‘in the foreseeable future.’

“Asked if he had any doubts that Maharis was really sick, Sterling Silliphant, the creator of the show, said, ‘Of course I do. I think he’s impatient to get on with his own career. He has had no regard for his company, for his co-star Marty Milner and the fifty or sixty other people on the show.”

But George had only shrugged earlier, when I’d talked to him about the director.

“He called me arrogant? Sure he thinks I’m arrogant. Because I hated working with him and he knew it. He happens to be one of those TV directors—and there are a few —who don’t know what the hell they’re doing. They think the set is a doll house and we, the actors, are their dolls. They smile when they come on the set, like, ‘Look Ma, I’m directing.’ And then, one thing after the other, they begin to butcher the script, the actors’ emotions, everything. About these guys I tell my producers, ‘Look, I don’t want to be uncooperative and say I’m not going to do t his week’s story. But you hired so-and-so as director? Well, just give me as little to do as possible.”

“So sure, I’m arrogant in this sense. But I’m an actor. Not a doll. I give my whole life to my career, my profession, and I don’t want some jerk to come along and ruin it all for me in a few days’ time. Oh, it’s a tough business, this TV. You don’t want to die out in it, and you can die easily if you don’t take care. People come. People go. A series goes off the air and you never hear of some of these people again. They’re like food to a gigantic monster and when the monster’s through with them he spits them out. all the thousands of pretty young things in Hollywood—they come in like food and they exit like vomit. I feel for them. . . . Believe me. I know that bit.

“Arrogance? They talk about arrogance? Sure, I’ve been arrogant in my time. But honest, too. I worked in a camp once, for instance. In the Poconos. I didn’t like any of the other guys there. Besides, they had money to go out nights and I didn’t. So I used to hang around with a horse on the farm next door. In my free time I’d just go over to that farm and I’d stand and I’d look at that horse. I’d look in his eyes and wonder if he knew I existed, what I was, how I felt. I’d look at his hooves and I’d wonder: ‘How are you so sure-footed?’

“Some of the guys, they thought I was arrogant by ignoring them and befriending a horse. But the fact was that I liked the horse more than I liked them. Arrogant, they say? I was in the Marines. There was a stupid top sergeant who used to give all the guys a hard time. So stupid it was pathetic. He had this coffee pot he used to worship. It was like his whole life revolved around that pot and when could he drink from it. He used to polish it up when he wasn’t doing anything else— which was often. He used to sit there and gaze at it, like it was a beautiful woman. Well, one day I decided to give him and his coffee pot a little lesson. It was after a day on which he’d been particularly rough with everybody. So that afternoon I decided to play Robin Hood. I took my 45 pistol and put .22 shells in it, using an adapter. Then I put the coffee pot on a fence and fired a dozen holes into it. That poor stupid sergeant—he never knew who spoiled his stupid coffee pot. He didn’t know anyone in the company who had a .22 pistol!

“Arrogant? Yes, I’m arrogant when it comes to putting up with a lot of people in this business Fm in. The phonies, I mean. They’ll tell you they’re going to put you in something and you’ll win an Academy Award. A lot of crap. People start by believing that kind of jazz and they lose track of their one true critic—themselves. For me, all this, what I’m experiencing now, what I’m going through now—this is only the beginning. If I listen to all the flattery, I’m liable to start believing it. And that’s dangerous. And if they threaten me —if they say I’ve got to do something or else—well, let them try. I don’t care. They can threaten me. They can take the Corvette. They can take all they want. Because I know where I’m going. And I don’t need anything but my own two feet to get there.

“Arrogant? You want to know some- thing? The thing Fm really most arrogant about is death. I don’t think I’ll ever fear it. In fact, it’s going to be my own way when I go. And Fm only going when I’m ready to go. They can shoot at me. They can aim cars at me. I’ll know they’re coming. And unless I know it’s time for me—they can go to hell. Because I just won’t be ready for them.”

—ED DEBLASIO

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MARCH 1963