Watch Out, R.J.—Robert Wagner

Bob Wagner’s at the top. But from the top, it’s a long way down. And with one misstep the trip can be made at jet speed. Maybe Bob recognizes this unpleasant fact. If he doesn’t, let him look at the experiences of other young men who were the sensations of other years—and then, through a frightening variety of mistakes, slipped as fast as they had come up. If they could speak frankly, they’d each give Bob advice based on actual events. And he’d be wise to listen.

Van Johnson might say: “Don’t let your personal life hurt your career.” Not so long ago, Van stood where Bob is now. He was even a similar type: the big, friendly, wholesome, all-American boy. His publicity followed that line, often playing up his comradeship with Keenan Wynn. Then Evie Wynn divorced Keenan in Juarez, Mexico, stepped across the border and was married to Van in El Paso, Texas. Overnight, the Johnson craze ended. His fans were startled and deeply shocked to find the bachelor so suddenly married, married to his best friend’s ex-wife. And so his fans deserted him.

Last year, Bob Wagner’s beginning career was briefly endangered by news reports that seemed like-wise out of character. He was the boy-next-door type, the most popular man at the prom. His fans had never expected to hear that he was dating a woman more than twenty years his senior. Of course, Bob and Barbara Stanwyck insisted that there was no romance involved; there was only companionship, plus an ambitious newcomer’s respect for a brilliant, established actress. Nevertheless, a jarring note had been struck. The dates stopped approximately with the production schedule of “Titanic.” No permanent damage had been done to Bob’s popularity, but the incident stands as a warning.

So does the flare-up of headlines about his “engagement” to once-divorced Terry Moore. Of course, the story was inaccurate and quickly denied (providing more publicity for their co-starring roles in “Beneath the Twelve-Mile Reef.”) But think what could have happened. It’s easy to imagine such a youthful, relatively inexperienced lad being strongly attracted to such a vital, exuberant girl as Terry. It’s easy to imagine them, half-persuaded by the headlines, being swept into an impulsive marriage.

The marriage itself might not have alienated Bob’s fans; usually, fans are happy to share in the glow of a young romance. But, in an town, a spur-of-the-moment match is risky business In Hollywood, a quick divorce brings disillusionment to a star’s admirers.

Currently, Bob continues to say that he won’t be ready for marriage until he’s thirty; he’ll be concentrating on his career. Fine! But if he sticks strictly to business, he still has hazards to face. He’s moving ahead fast.

Too fast? Guy Madison’s experience says: “Don’t get pushed beyond your capabilities.” As a newcomer with almost no acting background, Guy scored with a three-minute scene in “Since You Went Away.” Moviegoers promptly began clamoring for more Madison. But boss Selznick could oblige only with countless photos of Guy’s muscular frame. Guy himself was off in the wartime Navy, where a man seldom gets a chance to pick up any acting practice.

When he returned, his fame kept bright by all the beefcake shots, good roles were waiting for him. Too good. A choice example was “Till the End of Time,” casting him as a confused war veteran. Against such big-time acting competition as Dorothy McGuire, his handsome features just weren’t enough. He fumbled the assignment, and after that, offers were rare.

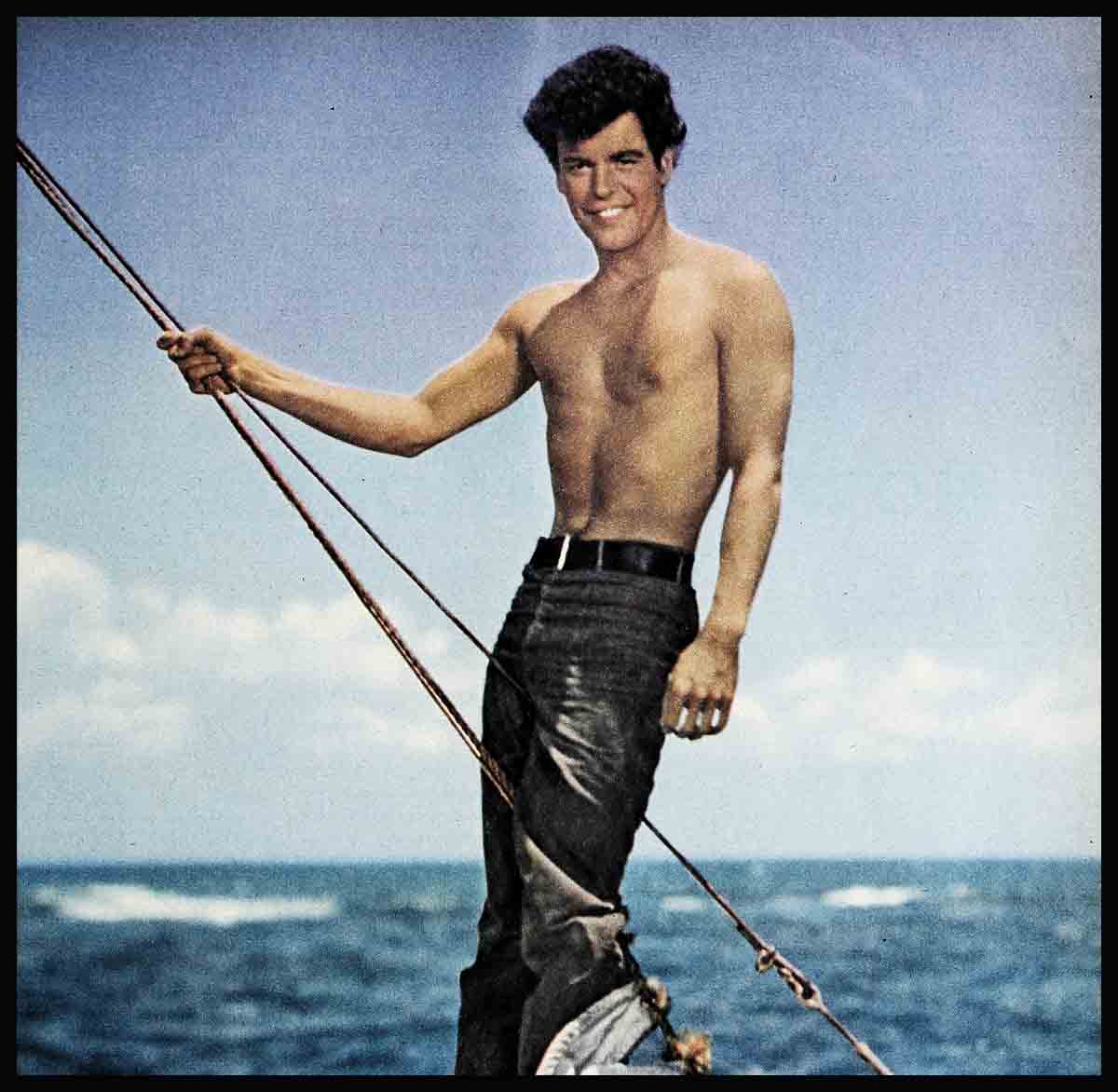

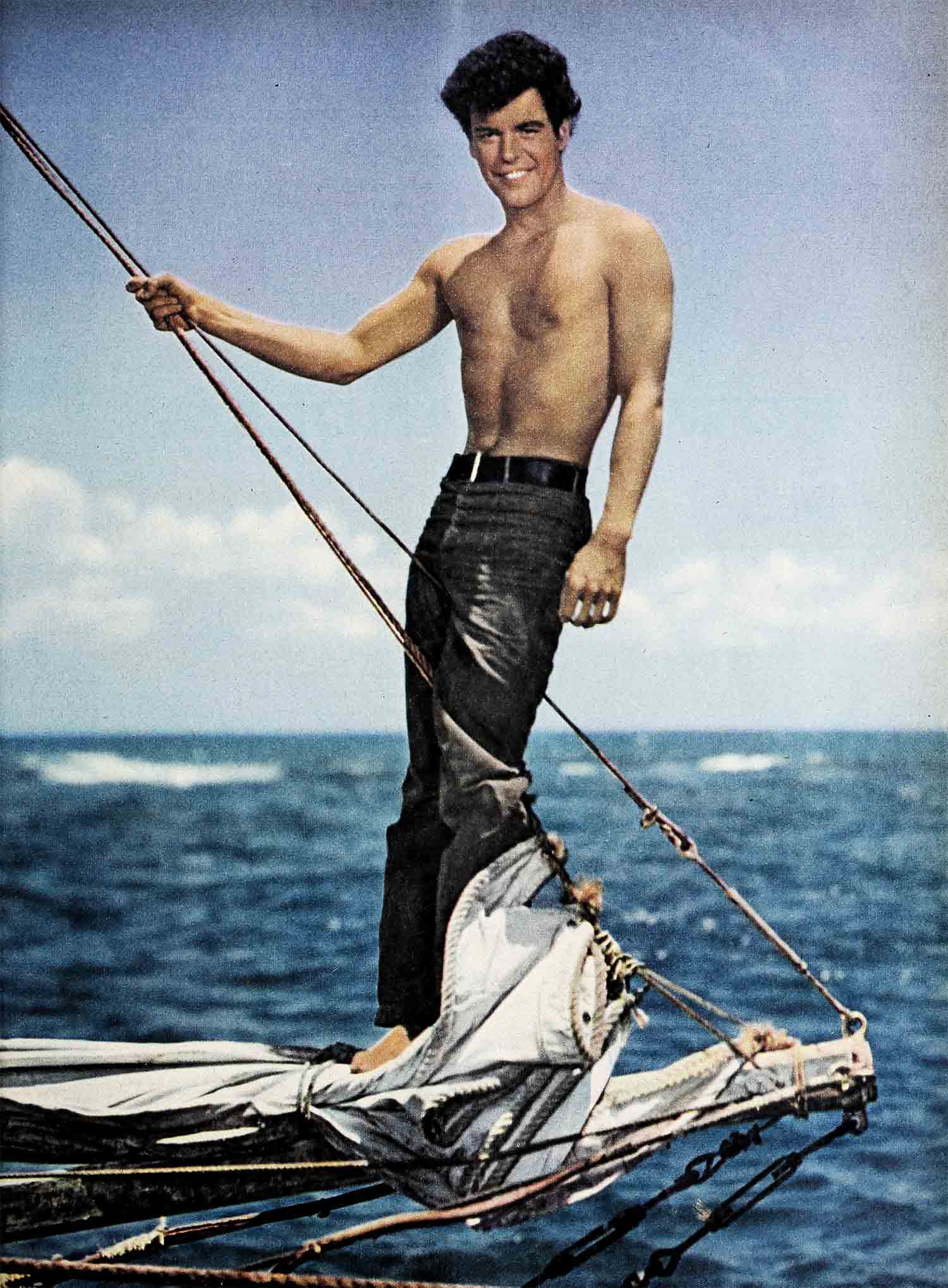

In Bob Wagner’s career today, no such threat looms. He began with a practically invisible bit in “The Happy Years” and advanced gradually to leading roles. Playing parts well within his present limits, he’s gaining experience with each one. But he must be careful not to be too much encouraged by his own swift progress. “Prince Valiant” will be a real test, pitting him against veteran-actor James Mason.

Should Bob play it safe with straight romantic roles that require no more than good looks? Actually, that isn’t so safe. Ask another Bob, last-named Taylor, who could warn R. J.: “Don’t let yourself get typed.” Almost twenty years ago, Taylor sky-rocketed as fast as Wagner. Women swooned over his classic masculine beauty. His perfect features seemed ideally suited to great-lover roles. He played one after another, and the topper came with his Armand opposite Greta Garbo’s Camile.

Enough was enough. With a depression just past and a war just ahead, the Hollywood trend was away from romance toward realism, away from pretty boys toward rugged he-men. And Taylor’s star descended. Feminine fans tired of merely admiring his flawless profile; male movie-goers, traditionally jealous of the girls’ idols turned thumbs down on Taylor.

Bob Wagner has two advantages over the other Bob: Handsome as he is, he’s a more familiar, average type than the young Taylor; his studio is casting him not in sentimental love stories but in vigorous action yarns like the two forthcoming CinemaScopers, about deep-sea diving and medieval adventure. Such surefire vehicles, with other prominent players co-starred, will carry him a long way. But sooner or later Bob will have to develop enough range to attract all types of moviegoers on his own. Though a girl might be content to watch his engaging face and his irresistible grin forever, she wouldn’t enjoy having to fight with her steady every time she proposed a Wagner movie.

Now suppose Bob’s all squared away in his choice of roles and his choice of off-screen companionship. He still isn’t safe; that perch on top of the heap is still mighty uneasy. Let him remember the moral to the Frank Sinatra story: “Don’t alienate the press.” The Sinatra mania of the ’forties was the biggest thing of its type to hit showbusiness since the Valentino hysteria of the ’twenties. Bobby-soxers shrieked and fainted wherever Frankie played; Hollywood welcomed him extravagantly.

Suddenly, it was all over, and an un-favorable press had plenty to do with the fiasco. To do Sinatra justice, newsmen (as hostile as the male moviegoers) were likely to greet any current idol with chips on their shoulders. But Frank’s own attitude, generally touchy and pugnacious, was no help. He got into a much-discussed fracas with columnist Lee Mortimer which cost him a $9,000 settlement. He made other enemies while at the top, and all were ready to plant a knife when he started to slip.

It was his personal life that started the downward slide, as in Van Johnson’s case. But sympathetic publicity might have softened the blow of Sinatra’s divorce and his marriage to Ava Gardner. He got no such publicity, and it isn’t hard to see why he didn’t. While he and Ava were courting, Frank threatened to “kill” a photographer who tried to snap the couple, returning from a jaunt to Mexico. Since their marriage, he’s been equally edgy.

A year ago, it would have seemed incredible that Bob Wagner—eager, affable, cooperative on all occasions—could ever become “difficult.” Yet, recently, disquieting reports have piled up, indicating that Bob’s grown coy about posing for pictures, that he has decided to mark most of his personal life off limits for the press. It doesn’t seem likely that the snubs could develop into the sort of open brawls that turned reporters, columnists and photographers against Sinatra. But the general trend doesn’t bode well for Bob Wagner.

The ladies and gents of the press are the ambassadors of the public, so a sensible star treats them with consideration. He’s even more thoughtful toward the public itself, when he meets it in person. Any star who doesn’t show respect for the public soon finds that the attitude’s mutual. Montgomery Clift broke this cardinal rule: “Don’t ignore your fans.”

Strong roles in “The Search” and “Red River” made Monty an immediate hit; thousands of fans were attracted by his sensitive features and his earnest manner. But their acclaim left Monty unimpressed. Autograph seekers were a bore; he brushed them off. Requests for interviews about his private life were an impertinence; he refused them. Personal appearances? Out of the question!

Clift expected to get by on acting ability alone. He even played hard-to-get with producers, turning down one script after another because it wasn’t precisely suited to his own tastes. When he finally did accept a role, in “The Heiress,” he turned out to be badly miscast. The picture did nothing for him or for the studio.

Again, Bob Wagner is apparently far from falling into such errors. Fans who’ve been lucky enough to meet him have found him thoroughly pleasant and obliging. He has gone out of his way to sign autographs and even drafted fellow stars to help the collectors build up their collections. But is his changing relationship with the press a straw that shows which way the wind blows? Flouting the press is an indirect way of snooting the fans.

The take-it-all-for-granted state of mind can be disastrous. Look at the strange history of Sterling Hayden, who cautions rue- fully: “Don’t get bored with the acting business.” Hayden became a star overnight in “Virginia” and “Bahama Passage.” A blond adventurer of spectacular appearance, he didn’t have to knock himself out learning his new trade. So he didn’t. “I sloughed the whole thing off,” he now admits. “I didn’t even read the scripts through—just studied my lines on the set before the scene started.” Casually, Hayden left Hollywood to return to the sea. War came; he achieved an excellent record in the Marine Corps and the OSS; with the arrival of peace, he drifted back to Hollywood, feeling no particular ambitions. After he’d ambled listlessly through three movies, Paramount gave him the old heave-ho.

Unlike Hayden, Bob Wagner didn’t merely stumble into an acting career by accident. He went after it avidly and intently, and when he was given his break he proved willing to work long and hard. But success has come to him early and in a big way. The flood of fan letters is only now approaching its peak; Bob’s first real leading roles have yet to be seen on the screen. When thousands of letters tell you that personally you’re wonderful, when millions of dollars in boxoffice receipts tell you that your performances are heartily approved—then, brother, you’re on the spot. Then the danger point is reached there’s a strong temptation to relax and coast. And you can’t coast uphill, or even on a level—not for very long, no matter how terrific your momentum. Coasting eventually takes you in only one direction.

Once you’re down, it’s considerably tougher to make the return trip to the top than it was to get there in the first place. It can be done. Hayden did a lot of thinking about his predicament; as a result, he changed his attitude, buckled down to work and is now in steady demand. Bob Taylor shifted to virile adventure roles and regained his boxoffice standing. Van Johnson, too, graduated from boyish parts—but his movie following never returned in full strength. Regardless of their splendid work in “From Here to Eternity,” Frank Sinatra and Montgomery Clift are in the same situation. An actor like Clift has to create an audience for each picture he makes; he has no substantial, devoted public.

Sole exception is Guy Madison, who wen into television to gain the experience he needed so desperately. He made a triumphant movie comeback in “The Charge a Feather River,” and the number of Madison fans is rapidly increasing. But it was a long haul. A little more foresight, a little more caution at the outset of Guy’s career would have made the struggle unnecessary.

At the moment, only one of these mistakes seems to be endangering Bob Wagner’s future. One would be enough. In case the examples of Clift and Sinatra aren’t convincers, Bob might listen to promising young actor, saying, “It’s so wonderful to have a big studio like Twentieth Century-Fox behind you. Photoplay has done a lot for me, too, and believe me I appreciate it. It takes so much. It takes the whole works. So many people being nice to you, working with you, caring what happens to you. You can’t get there unless they’re all behind you.”

It was Bob Wagner himself who said that—one short year ago. Now he’s gotten there. But a star needs the same help—from the studio, press and fans—to star there. If Bob keeps this in mind, he can look forward to the solid, lasting success that he deserves.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1953