Is It D-Day Again For Doris?

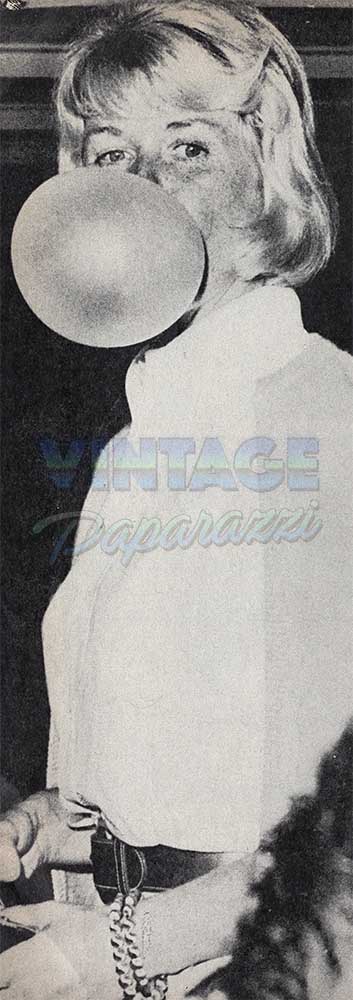

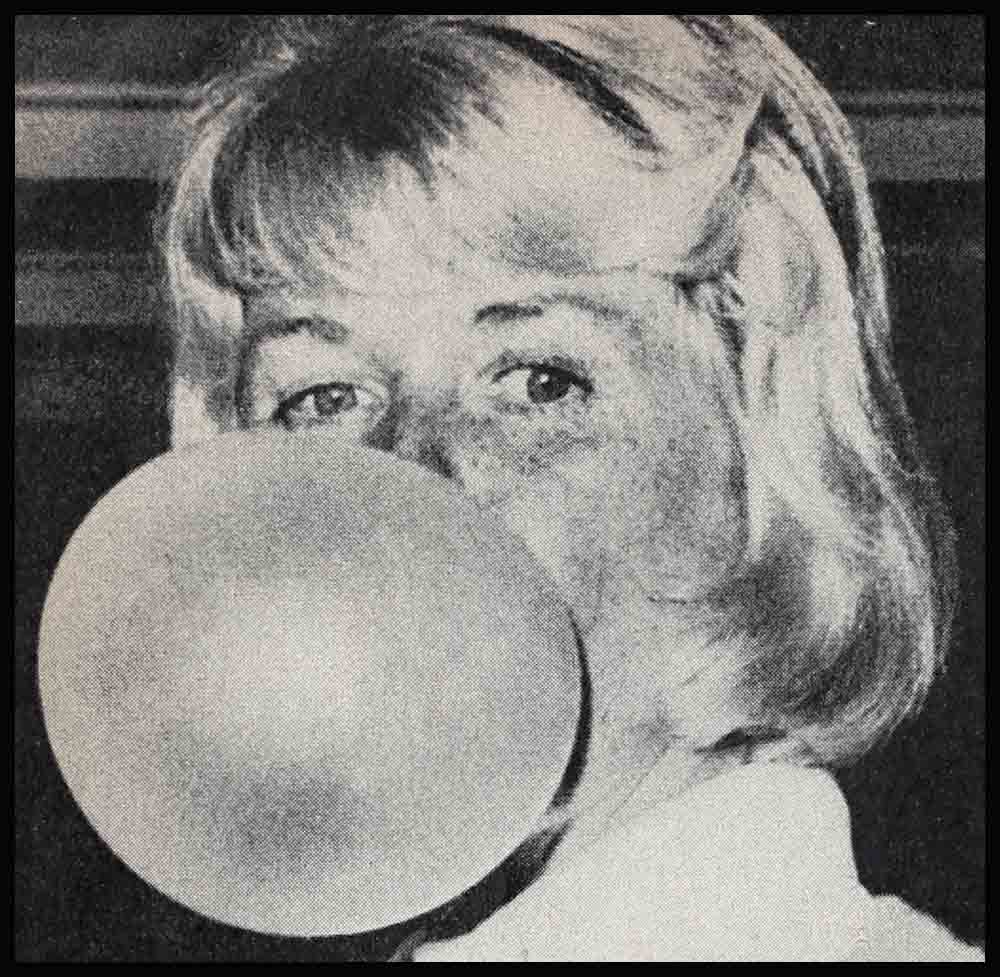

This past September, a tall girl with yellow-butter hair and a church-supper face powdered with freckles like a cinnamon bun stood up in her box seat at the Los Angeles Dodgers baseball stadium and did a curious thing, even for a rabid Dodger fan. As if in defiance of the photographer who was training his Speed Graphic on her—and perhaps even of the world—this girl, with a glint of rampant mischief in her eyes, blew up the wad of bubble gum in her mouth into a huge pink balloon that seemed to say, “Well, okay, pal; you want my picture? Get this!”

The lady with the bubble gum was, as it happened, a customarily reserved and even curiously shy Beverly Hills matron of thirty-eight named Mrs. Martin Melcher, the mother of a twenty-year-old son (by the first of three marriages); the possessor, with her current husband, of some $6,000,000, give or take a bank account or two—and not the type of person who would ordinarily stick her tongue out at anybody.

But then Mrs. Melcher—or actress Doris Day, as she is better known almost everywhere—was apparently on the brink of one of the more critical moments in her life.

“Call me crazy, if you like,” said a Hollywood observer, “but when those separation rumors about Doris and Marty began popping up just a few weeks later, I remembered that cocky, almost defiant picture of Doris with the bubble gum, and I thought to myself, ‘Well, this is a doll who no longer cares if school keeps.’ Maybe I was reading things into that gesture, but add two and two in Hollywood—and you always get five.”

The Melcher separation rumors and Doris’ bit with the bubble gum (that picture hit newspapers all over the country) could have had no relation whatsoever. Some people, of course, see significance in anything. But it is a matter of record that not long afterwards, husband Marty Melcher was off in San Francisco “producing a new play” while Doris remained at home. That was when the first hint of a possible rift between the “always happy” Melchers slithered into print. “Doris and Marty Melcher are readying an announcement,” said Mike Connolly, in his Rambling Reporter column, and a shocked Hollywood gasped, “Not Doris and Marty!”

Just days later, forty-six-year-old Marty Melcher was again away, this time in New York “making arrangements for the opening of his new play,” while Doris, his wife of eleven years, stayed in Hollywood. “Doris is working in a picture, Universal’s ‘The Thrill of It All,’ ” Marty explained. “She didn’t come to New York because it would take too much time.”

But the rumor mills were still churning. “Doris Day, America’s favorite movie star, will be making headlines out of Hollywood in the near future,” declared New York columnist Dorothy Kilgallen, with Sidney Skolsky and Sheilah Craham adding their voices lo the now familiar chorus.

Most startling of all, however, was a somewhat incredible item in Earl Wilson’s column. Said Wilson: “Hollywood won’t believe the rumor that Doris Day’s sweet on a N. Y. Yankee star—first, she and Marty Melcher are very rich and seemingly happy together; second, she’s a Dodger fan.”

Was it, then, D-Day once again for Doris, everybody’s girl next door? D-Day for the much, much written-about but strangely little-known girl from Cincinnati who “had made millions swinging on the garden gate with a prim neckline and a song in her heart”? She had married first at sixteen, again at twenty-one, and once more at twenty-seven. Those first two husbands of hers, musicians both, were forever, in Doris’ mind. “The Trombone Player” and “The Saxophone Player,” though the Trombone Player had given her her son. She had the happy knack of “forgetting things that I don’t enjoy remembering. I never look back, and I can barely remember my first two marriages.” But of her third husband, Marty Melcher, the wide, comfortable shoulder on which she leaned, the man to whom Doris always ran if a mouse appeared or a fuse blew . . . of him she could say, at least as recently as just a few years ago: “Marty is my understanding husband and my favorite friend.” And Marty would quip back, “The secret of our happy home life is, half the time I let my wife have her way, and the rest of the time, I give in. So we get along fine.” He’d smile when he’d say it.

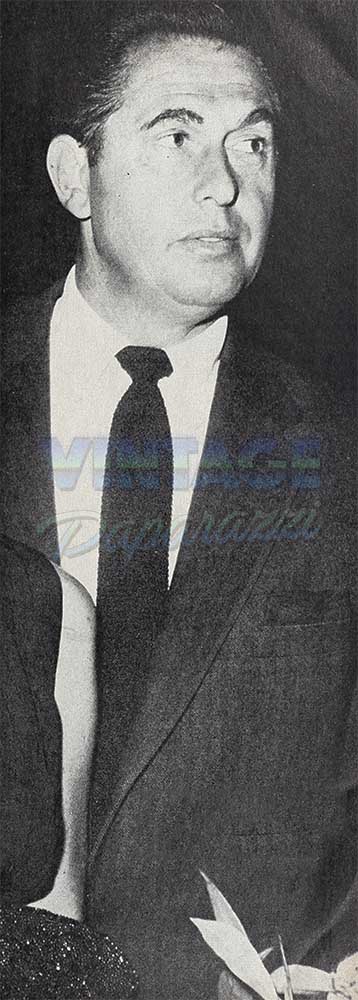

Only a year or so ago, Marty Melcher, tall, sun-tanned and looking very successful (which he is) sat in the office of his and Doris’ Arwin Productions in Beverly Hills, and over a wide desk flanked by a trio of telephones, spoke of his wife’s “colossal box-office appeal.” It was nothing to he modest about.

“Doris,” Marty explained affectionately, “is a one-lady factory, a commodity that turns out so much a year and brings in so much money. Just like a car. Occasionally we must retool and put out a slightly different product. But there is no big inventory to worry about.” Marty’s grin became even wider. “What’s more,” he went on, “Doris can sing, too.”

Did some of the reasons for the printed speculations and whispered rumors begin then? Had Doris, who once said, “I could live in a trailer camp and be as happy as a toad,” finally suffocated in that aura of too many millions—rebelled at the prospect of a future that saw her only as a one-lady factory bringing in so much money a year? The Gold Mine, it is whispered, would rather be a woman.

Had Marty, the once-understanding husband, added too many telephones to his already wide desk, forgotten the secret of those halycon days when life was still beautiful, or beautiful enough, in the house on Crescent Drive? Or is it simply that Doris Day has a chronic inability to stay happy—despite her seeming placidity?

Even people who are fairly close to Doris —and there are not too many—are unaware of her emotional conflict.

You look at her and she appears to be the girl you’d most want to take to the office picnic. Doris has had, tor years, her own soda fountain at home, and she once told a friend, “Put one of Blum’s extra-sincere ice cream sodas in front of me and I get a look of ecstasy on my face.”

Reminded that her husband had once tagged her “the girl who tried to grow up and never made it.” Doris looked startled for a second or two, then smiled—but not with her eyes. “Well. it’s probably true, but I am more grown up now,”

More grown up she may be, but Doris still believes that her right profile is better than her left, still insists that she be photographed only from the right. She is said to fly into “a panic when a few strands of hair stray out of place.” She cannot bear to have her religious beliefs—she is a Christian Scientist—or her real age revealed. “She looks twenty-nine,” said one man, “and she’d like to keep it that way.” Her concentration on what she believes are the “happier things of life” is so intense, a friend reveals, that she can barely tolerate having sad or sick people around her.

Her single passion is tennis, and her favorite extravagances are perfume and clothes. For a woman who rates herself as superbly organized and a dedicated perfectionist, Doris still displays curious, if charming. contradictions. “She just loathes decisions,” a friend chuckled. “Instead of making up her own mind, she’d much rather call Marty and interrupt a business conference, just to ask him about the monograms on some new bath towels.”

These are minor quirks, of course, but they reveal a Doris Day that few people really know. A Hollywood publicity woman, a girl who is genuinely fond of her, declared: “Actually, Doris is extremely reserved. Marty is her closest friend. Doris’ friendship always stops at certain levels.”

The publicity woman was silent for a moment, then laughed suddenly at something she had just remembered. I asked her to talk with an important New York writer, hut she refused. Finally, the only way I could get her to do the interview was to promise her the biggest fudge sundae she ever had at Blum’s!”

Congenitally shy, and always reluctant to have large groups of people at her home, Doris, say intimates. is literally terrified at the thought of playing hostess, always makes sure that the rare dinners she gives somehow wind up around nine o’clock.

Apparently against her own inclination—or possibly because of Marty—Doris has become Big Business. (“I never really wanted a career,” Doris once said, “but I’ve been sort of trapped by one.”) She was, indeed, anything but a top star when she first met Marty Melcher.

Doris, then in her early twenties already had a son, Terry, by her first husband, Al Jorden; and she was all but inconsolable over the breakup of her second marriage to George Weidler, a saxophone player in the Les Brown band. Melcher himself had been the husband of singer Patti Andrews (of the Andrews Sisters), and he was a talent agent in partnership with Al Levy. Doris, Levy’s client, was then singing at New York’s Little Club.

“I didn’t know Doris,” Marty has said. “but since she was a new addition to our stable, Al Levy asked me to catch her act. After I talked with her, I went to the phone and called my partner. ‘Listen. Al,’ I said, ‘unload this dame; get rid of her fast. She bawls all the time.’ ”

Before too long. Marty Melcher had not only taken over active management of Doris’ burgeoning career. but of her life. He was the man who could handle balky lawnmowers, faulty plumbing, blown light fuses and the weekend shopping. One day, Doris’ young son Terry said. “Why don’t you marry the guy?” They did marry—on April 3. 1951. Doris’ twenty-seventh birthday. Marty legally adopted young Terry, and life began again for Doris.

For Marty, life changed radically, too. Like Doris, he gave up liquor and tobacco, became a Christian Scientist. “I used to be a pretty sharp wheeler-and-dealer.” he told a friend. “But now I even like myself. I didn’t before.” Seemingly, it didn’t matter that his wife was a kind of Gracie Allen character, whose foibles and quirks merely brought a resigned, “Well. that’s Gracie for you.” She’d get vague or bored at mentions of one hundred thousand dollars, or of contracts that called for a quarter of a million dollars per picture. Producer Joe Pasternak, who virtually had to hammerlock Doris into doing the memorable “Love Me or Leave Me,” claims “Doris was intimidated by anything over five dollars.”

Marty, of course, was the man who, as Doris said, “spoiled me rotten: the softest, gentlest man I ever knew.” He was the man who could sit on the edge of his wife’s bed. when she was in one of her deep-indigo moods, and sing Christian Science hymns to her for three hours, until she drifted off to a dream-tossed sleep. A panic-stricken Doris needed Marty more than ever, in 1954, when she feared that she had cancer. Actually, close friends say now, Doris was frightened by a small breast tumor that proved to be benign.

Over the years, since then. Doris’ hot-buttered-sunshine smile has led her—and Marty—straight to their own version of Ft. Knox. Her freckle-faced son Terry, now twenty, signed a Columbia recording contract not long ago (“Why, Terry, I didn’t know you could sing,” Doris was supposed to have said), but Terry left home to go to New York to “prepare himself for the diplomatic service.” Marty, increasingly the tycoon, apparently has found little time lately to sit on the edge of Doris’ bed and croon hymns to her.

In December, 1961, Melcher suddenly announced that an earlier, $26,000,000, eight-picture deal with Columbia had been “terminated.” “The contract was cancelled at my own request,” Marty stated, “because 1 didn’t want to tie Miss Day up for more than two films at Columbia.” Melcher added that “the peculiarity of the business today” was his reason for the move, saying also that he wanted “Miss Day’s contractual obligations to be more flexible.” Marty also revealed. then that he had been talking with several financiers about starting his own studio, probably doing “plays—or movies—with stars other than Miss Day.”

If Doris was upset—or even bewildered —she made no public comment. As always, Doris wanted only to work, and to keep on working. Or so it seemed.

“She has so much energy that I don’t know what would happen to her if she didn’t work,” a woman friend declared. “She tries to burn up that fantastic energy of hers, when she’s not making a picture, with daily tennis, swimming, walking her three poodles and shopping. When Doris can’t find anything else to do, she cleans house. She’d really like to quit working. but she just wouldn’t know what to do with herself. So Marty has her sewed up with pictures for the next couple of years.”

“I’m a difficult character to live with.” Doris confessed not long ago. “I’m bossy with Marty. and I criticize him. I keep the house too clean and I don’t cook too well. I’m a lint picker, and I hate clothes lying around on chairs. And when we do go out, I make poor Marty even stand inspection on his suits. For a while, my mother was living with us and running the household, and Marty had his favorite joke. ‘I give you notice,’ he told my mother, ‘that if that wife of mine ever acts up, I’m the one who gets custody of you.’ ”

Prophetic? Perhaps. But it is in the things that Doris does not say or do that one sometimes gets a clue to her reactions. Was Doris incensed or even publicly vocal about ali the separation rumors, the reports that she had found a new interest in a Yankee baseball player? Up to this writing, anyway, Doris has been silent. But Marty indignantly phoned Louella Parsons.

“I don’t know where all those stories started,” Melcher shouted. “We have always had a nice, calm, quiet life together, and never been apart throughout our marriage. Then I branch out a little, put a play into production and suddenly all those dumb noises start up. The whole thing is absurd. I love my wife, and she’s a wonderful girl. We have no problems.” Miss Parsons concluded her report with a masterpiece of comment. “Doris,” she wrote, “agreed with her husband.”

If the Melchers do drift apart it will be a tragic ending to Hollywood’s favorite idyll. Even if the rumors fade to nothing—as we hope, the question remains: Why did the rumors begin?

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1963