Family Man On The Loose—Donald O’Connor

One evening about this time last year, Donald O’Connor skidded his Jaguar to a stop before the Bel Air Hotel in Hollywood. He’d driven the 300-mile haul in from Las Vegas, where for four rugged weeks he had knocked himself out at the Sahara beating Marlene Dietrich’s record.

Waving back the porter who reached for the stacked suitcases holding all his personal possessions, he yawned, “Get ’em in the morning. I’m dead.”

Up in his suite, he shucked off his clothes and idly switched on his TV set. The minute the picture focused he let out an agonized groan. That minute they were starting to hand out the “Emmy” awards—television’s Oscars for the year’s best performers. Don O’Connor knew he was to get one, and it was a great honor. He had promised to be on this show, but in the rush he’d forgotten all about it.

For a second, Don considered dashing down to the studio and out on the stage in his pajamas. Then he raced half-naked through the lobby and out to his car, tossing bags right and left until he got to the bottom where his tux was packed. Upstairs again, he juggled collar buttons and studs, groaning when his name was announced and the emcee told embarrassed lies. But he might save face if he could just make it under the wire. As he reached down to flip off the set and run, he heard, “Thank you—and good night”—and a cartoon commercial flickered on to mock him.

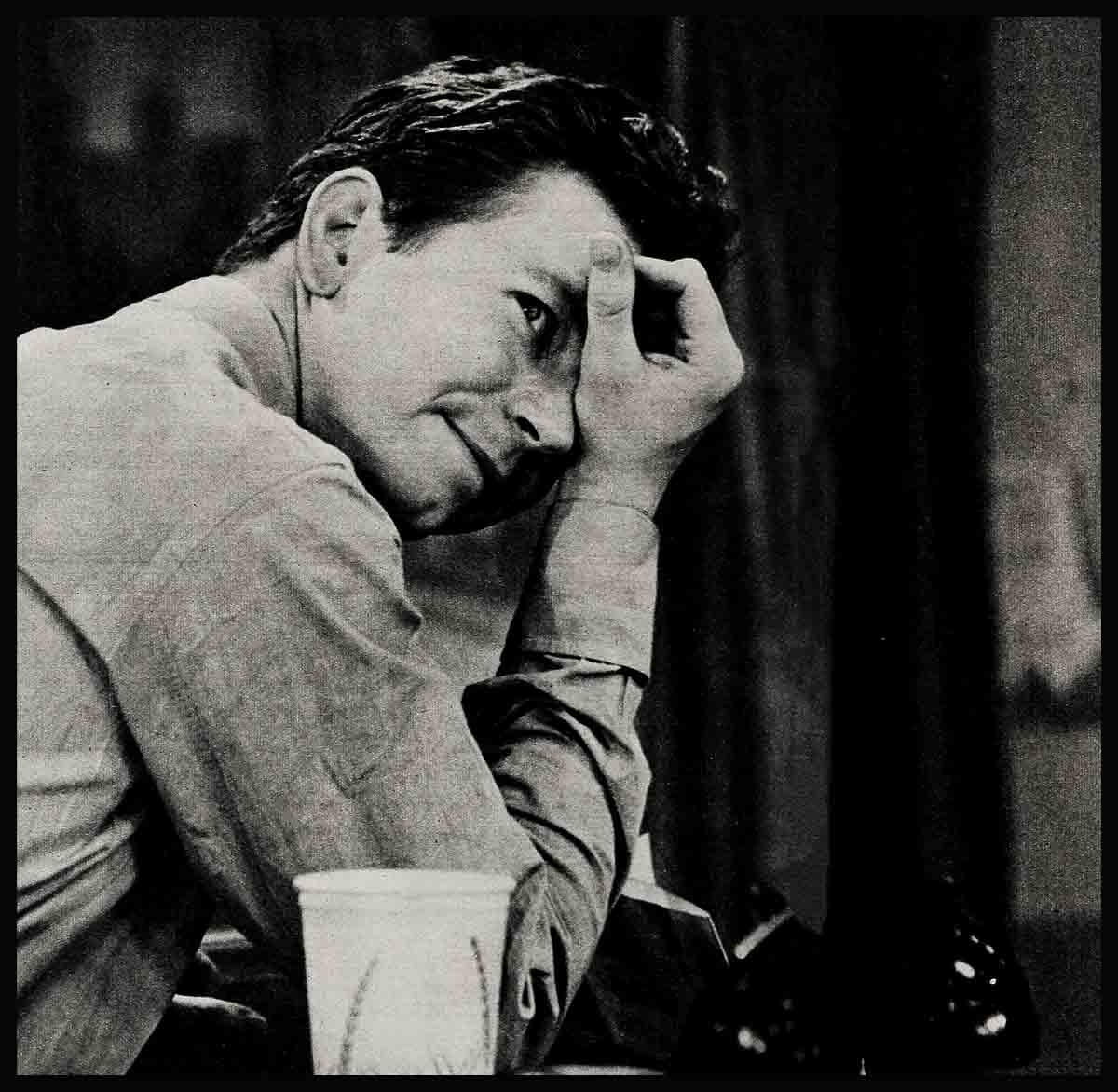

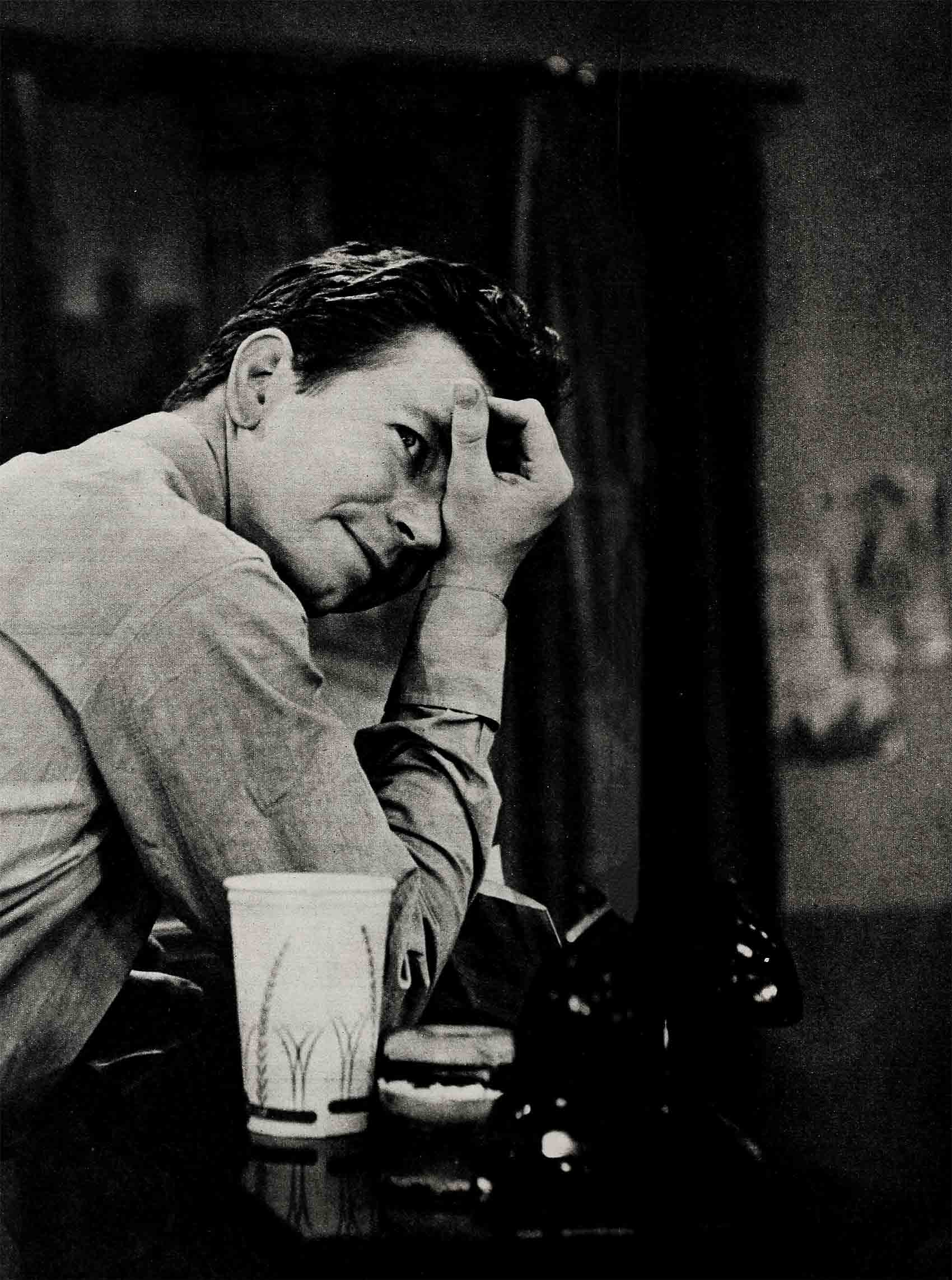

Donald O’Connor dropped like wet spaghetti and surveyed himself dismally in the mirror. His tie was cockeyed. His shirt cuffs flopped loose. His beltless pants rippled around his ankles. His hair stuck up and his “dress” shoes were brown.

“Get you,” he told himself. “All dressed up and no place to go!”

Professionally speaking, it’s too many places to go that’s Don O’Connor’s trouble right now. Donald David Ronald Dixon O’Connor sports a top talent for every one of his names, and it would be very convenient indeed if he had a separate body for each. Like another thirty-year-old (named Alexander) there isn’t much left for O’Connor to conquer in his world of show business. As any casual TV twiddler or movie-goer knows, Don can dance with the effortless grace of Astaire, croon with the golden ease of Crosby, be as captivatingly nuts as Danny Kaye and act with the best of them. There’s no business like show business for him and nobody in show business like Donald David Ronald, etc.—as he recently proved in the 20th Century-Fox musical of the same name. Ethel Merman, no slouch herself, tagged Don, “The greatest concentrated hunk of talent on the screen.”

So don bumps into himself coming and going as he tries to meet the Hollywood demand. Five mornings a week he pushes open the door of a pink stucco bungalow on the General Service lot where, as producer, director and star of his hit TV show, Here Comes Donald, he spends $50,000 of the Texas Company’s money each week, meets a payroll of forty-nine employees. From his Mussolini-sized office he masterminds a galloping career which includes movies at $200,000 a crack, Las Vegas bookings at $30,000 a week, a song-publishing firm and a one-man idea factory which grinds out everything from movie scripts and nightclub skits to oil well ventures. From all this he figures to collect almost a million bucks in 1955.

For a guy who has been chasing show business rainbows since before he was born, this would seem to be a situation approaching Paradise. His mother was a dancer. Donald made his debut in the O’Connor Family act at four months. By his first birthday, his acrobat brothers, Billy and Jack, were tossing him back and forth over the audience like a football. All his boyhood the same shifting show business pattern prevailed as the O’Connor Family trouped vaudeville circuits, carnivals and clubs, gorging on chicken one week, feathers the next. In his twenty in-and-out years around Hollywood, Don had more ups and downs than an elevator— until he finally stuck on the top floor. Only last year he was picked to hand out Academy awards to his peers.

But Donald O’Connor floated in no transport of joy—nor does he today. In this flight to glory something is missing. The empty other side of the picture lent a wistful meaning to Don’s self-appraisal that night as he stood before the mirror at the Bel Air. Because Don is a dangling man—all dressed up with fame and success, but no place to go for happiness. And ironically, the knots that tie him up professionally leave him at bare loose ends in his private life.

Since Don and his pretty wife Gwen finally called it quits a year and a half ago, after nine years of marriage, Don has rattled restlessly around like a loose bolt.

In that time he has lived in four separate places. First, the Bel Air Hotel, which he deserted because it was “too public and too expensive.” Yet he paid almost as much as the $1200-a-month there for the next place he picked—a modern hilltop hacienda in Benedict Canyon, complete with swimming pool, hi-fi system and plush furnishings, besides completely redecorating most of the rooms. This he abandoned soon on the flimsy excuse that it was “too buggy,” with spiders, centipedes and other real and imaginary varmints swarming around. Came next a house in Malibu where the fishing he loves was swell, but that was soon “too far out.” So he took a small apartment at the Villa Madrid, where he’s camping today—and hating it.

In all this time, Don has rocketed away from Hollywood, as if fleeing the plague, almost every week end and every free stretch after pictures and between TV seasons. Last fall he flew off to Hawaii on a day’s inspiration for a week and jittered most of that time in the Royal Hawaiian Hotel because it rained five days out of the seven. The rest of the time he chased around Honolulu with a private detective, hunting thrills, a la Winchell. This winter he tore off after the final “Cut!” of each TV film to scattered refuges, including Snow Valley, where he ran into the heaviest fall of the year, got snowed in, couldn’t budge on skis or anything else and almost went crazy. Next he went to Palm Springs for a rest and stayed up all night helping open a new guest ranch. Other exits to the Mojave, Mexico and scattered points have been just as fast, frantic and unrelaxing.

These are symptoms of discontent even in a natural skitterbug like Donald O’Connor. Of course, it’s true that Donald is and always has been as charged as a bottle of pop, physically, mentally and nervously. His wiry body, which actor Bob Ryan, a physical culturist, calls, “the best physique, pound for pound, in Hollywood,” requires exercise, and the natural coordination you see on the screen has made him an expert, easy athlete. Don learned to ski in two days, entered a race on the third. As a fourteen-year-old he competed in Bing Crosby’s first golf tournament and, although he barely knew a mashie from a mid-iron, won a prize—twenty-four quarts of motor oil which he had to give away because he was too young and too poor to own a car. He’s a deadly boxer and once broke his best friend’s ribs teaching him to handle his dukes. Last year in Las Vegas the national convention of skeet shooters asked him to join the fun. He shattered eighty-five out of 100 clay pigeons although he’d never banged the game before.

Behind Don’s bland, boyish face, too, is a mind that races on something or other every waking minute. Stuck one week end near San Diego, he stayed up all night in his room writing 200 gags. Another time he came home with ten new song lyrics. He always has been a speed nut, with a trail of Bugattis, Jaguars and other sports cars around him since his teen-age days when he hopped up jalops with dual carburetors and twin pipes. For years he’s tried to stop smoking but admits defeat “because you can’t light a candy bar.” Wherever he is, O’Connor jitters around unless something active is going on.

Don explains his fast week-end exits from Hollywood as therapy to “relieve the pressure and change the scene . . . charge my batteries and fresh up for more work”—which is certainly logical. To give out what Don gives day in and day out, it figures that he has to stay as wound up as a thirty-day clock. But allowing for other occupational therapy and his own native restlessness, there are other unmistakable signs that Donald O’Connor is unhappy with his status as a Hollywood bachelor.

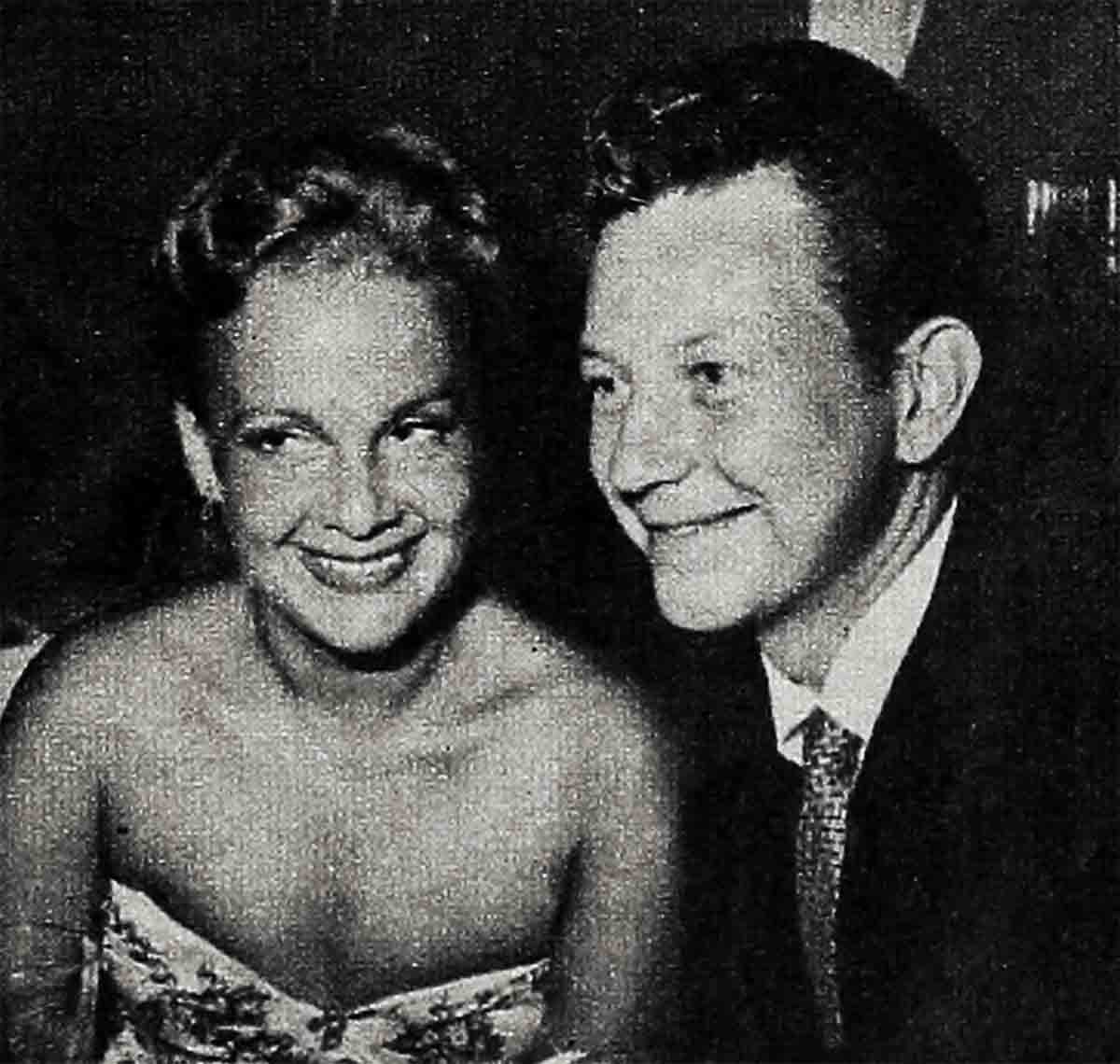

For one thing, Don has failed to find any satisfactory romantic attachment since he broke away from Gwen. For a while he squired Marilyn Erskine around Hollywood, but that failed and Marilyn got married. He has taken out Sylvia Lewis, a pretty young dancer, but nothing came of that. Most of Don’s fun partners are girls who happen to be where he happens to be, with no meaning whatever except the evening’s pleasantries. In Palm Springs he sometimes teams up with Carol Morton, daughter of the manager of the Ranch Club where he likes to hang out. Around Hollywood he’s seen mostly with Gloria Noble, a pretty brunette, TV actress and dancer, whom Don met at a Colgate Comedy Hour cocktail party two years ago. Gloria was married then and so was Don, technically. When he was free he called for a date and if there’s anything halfway steady in his life it is Gloria. They know each other well enough to go off together on holidays with Don’s pals, and last Christmas Gloria came through with two golden, diamond-studded, miniature dance pumps made into cufflinks and bestowed with a Christmas kiss. But when you ask Don about Gloria Noble he dismisses the subject with a curt, “Not serious.” And if you press him, he’ll argue, “How can you fall seriously in love with anybody when you haven’t got any time to spend with her?”

This argument is a handy and perhaps valid explanation of Don’s almost total lack of social life in Hollywood, usually extremely comforting and welcomed by young, attractive and successful divorcés. But as a stag Donald O’Connor acts like a lone wolf. He ducks Hollywood parties, shows up at the Strip’s glitter mills only to catch acts he wants to study, and prefers to eat late at night in off-beat, remote cafes. Last New Year’s he dropped into the Racquet Club in Palm Springs wearing riding breeches, a sport shirt and a white leather jacket, took a look around at all the formally attired Hollywooders sipping champagne, had a quick Scotch at the bar and departed.

Don’s circle of friends today has shrunk exclusively to the people who work with him. His two-room apartment at the Villa Madrid is next to Sid Miller, a diminutive pal from his early Hollywood days who bosses the writers and capers with Don in the video funny business. Sid flew with him to Hawaii last fall along with Ralph Grosch, a former movie stand-in, now production assistant of Here Comes Donald. Another former stand-in, Phil Gerris, is his dialogue director. That trio, along with Don’s press agent, Glenn Rose, and an associate of his song publishing firm, Jesse Stool, make up the current O’Connor set, double-date with him around Hollywood and take off with him on his escape excursions. Besides his niece, Patti, who writes for his show, and his brother Jack, who runs a dancing school in Encino, no one else in Hollywood can be called an O’Connor intimate.

Two other facts round out Don’s looseend picture: He has lost twenty-five pounds and he’s still seeing a psychiatrist. The first he’ll explain as, “I always lose weight when I’m working,” and the second, begun when his marriage was faltering as a sensible attempt to save it, has become not only a deep interest but a part-time hobby. Don bought a batch of books on psychology and likes to study them intently far into the night. But neither loss of weight nor solitary self-dissection is exactly a sign of contentment.

For a long time, all this was explained on the theory that Don O’Connor was carrying a torch built for the Statue of Liberty. One friend goes so far as to say, “They wrote that song, ‘Let Me Go, Lover, for Don.” Gwen has let Don go officially, as of February 5, when she finally married Dan Dailey in Las Vegas after a yes-and-no courtship carried on ever since Don moved out.

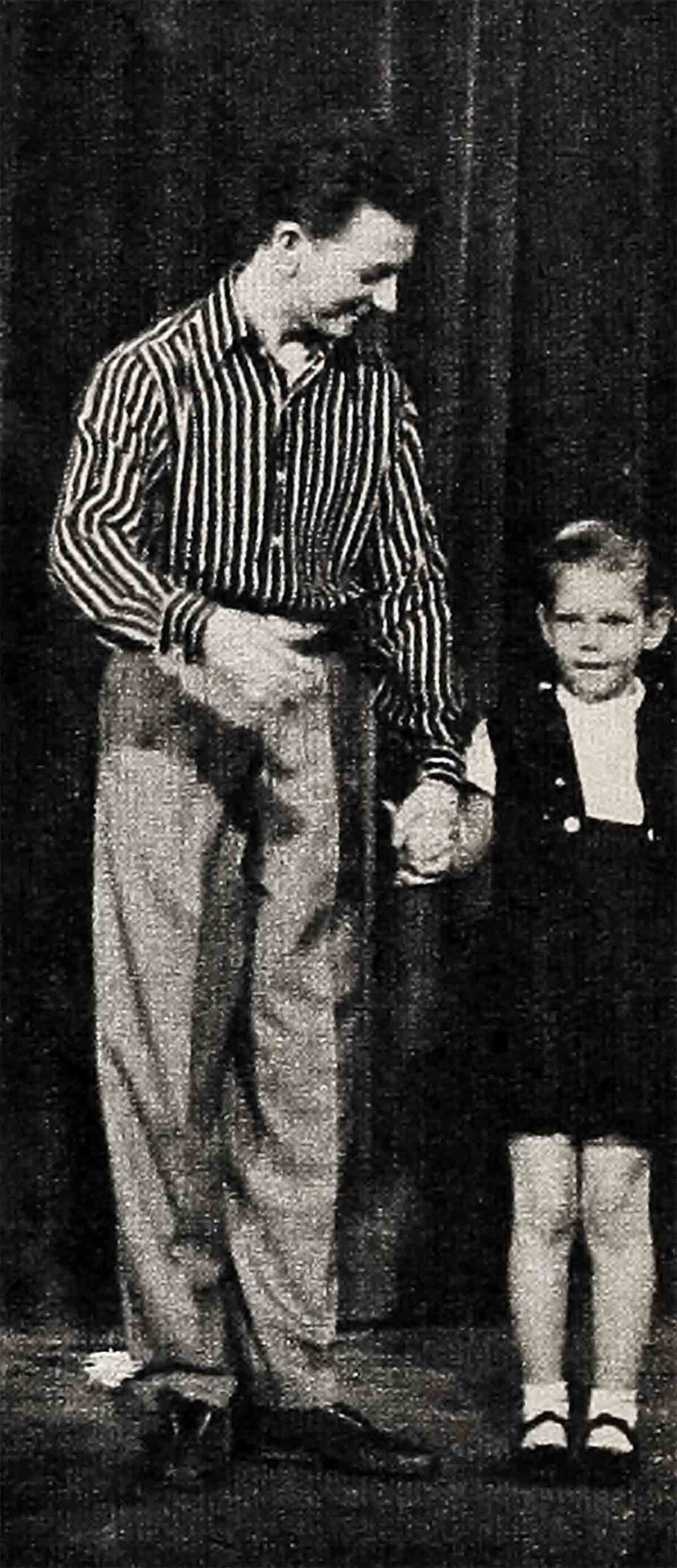

But even before Gwen married Dan, Don gave small evidence of the green-eyed monster. Hopeful gossips were disappointed by the absence of explosions when Don bumped into Gwen and Dan around town. He even played Dan Dailey’s son amiably and without incident in No Business Like Show Business. After Gwen filed for divorce, they were so friendly that reconciliation rumors blossomed every second week. Don has had Donna, his eight-year-old daughter, with him whenever he wanted her, once for two straight months at Malibu, and only chuckled when that sassy miss teased him with, “I saw No Business Like Show Business yesterday and I thought Dan Dailey was great!”

Just the same, there is a causative link between Don O’Connor’s broken home and his restless, frustrated existence today—and an even longer chain reaching back to his earlier life. Every man is the sum of his experiences. A look at Donald O’Connor’s shows why he can never be a happy man as long as he’s drifting around without ties.

His childhood was a blur of shifting scenery as the O’Connor Family vaudeville act rambled around the forty-eight states chasing a living. The only permanent home Don ever knew was his Uncle Billy’s and Aunt Josie’s farm near Danville, Ilinois, where the clan retreated when out of bookings and broke. The only formal schooling he can claim is two brief years there; the rest of the time he had to pick up his education on the fly—likewise his friends. They were trunk-raised kids like himself who, like himself, played in alleys outside stage-doors between acts, or in the dim-lit halls of small-town hotels, making toys out of anything handy. Don remembers one child who used to take out his glass eye and play marbles with it. When he ran out of kids he tagged after elevator boys and bellhops—wherever he could find friendship. Once, when he was missing, they found him singing chummily with a Salvation Army band. Don still can’t bring himself to say, “Goodbye.” He says hopefully instead, “I’ll see you.”

But in this helter-skelter raising, there was always one word etched in his being—family. The O’Connor act changed names countless times for billboard purposes, but always the idea of a family group was there, not only in billing but in fact. Don’s dad Chuck, an ex-circus acrobat, fell over dead in the wings a few months after Donald was born and his sister Arlene was killed by a car in front of a Hartford theatre when Don was only one year old. But Effie, his dancer mother, Jack and Billy, the baby-tossing brothers, sister-in-law Millie and niece Patti, carried on, with Donald doing almost everything, including playing bearded old men. And whether collecting $1200 a week for the act or $6 and meals—as they did once—they stuck together. They played the Palace Theatre and strolled in glory down Broadway. They got pulled in by cops on suspicion of being the Lindbergh baby kidnapers (because Baby Patti looked just like the missing tot) on a forage into rural Canada. But Don never was without the warmth of homefolks, although there never was a home. “I used to have one big wonderful dream,” he has recalled. “My own back yard.”

Although his entrance into Hollywood was definitely unsettling (he was almost killed in California’s destructive 1933 earthquake) Donald later made that backyard dream come true in typical family style. After he had finally clicked as a star at Universal, Don acquired not one but three back yards, complete with houses, for his mother, brother Jack and himself—all in one week at the combined outlay of $45,000. By that time, of course, the knockabout kid had realized another dream—to have a wife, family and a home of his own.

Much has been written about the marriage of Don O’Connor and Gwendolyn Carter. What made them find living together unbearable after nine years and a daughter who is firmly lodged in both their hearts will still stir up an argument in Hollywood. Some say Gwen jealously longed for a career of her own, which, perversely, Don encouraged by getting her an agent and spotting her in a few of his shows. Others say Don left Gwen alone too much after Francis The Mule and the Colgate Comedy Hour put him back on the frantic career merry-go-round. Gwen eventually secured her divorce on the grounds of “mental cruelty” which means nothing at all.

But certainly there were recurring crises in the O’Connor home, arguments both in public and private, and more than a few times Gwen barked, “I want a divorce!” and packed her suitcase. Usually: consideration for Donna smoothed these over. “Donna always played Cupid in that home,” as one friend has put it. Once when Don moved out to a hotel, reporters got wind of the rift and badgered Don into a press conference there. But when they arrived he was gone. They finally found him back at home playing with Donna and trying to explain why Daddy had been away.

In fairness to Donald it must be stated that, while he was undoubtedly at fault as much as his wife, the pressure to separate was on Gwen’s part. Throughout the familiar pattern of Hollywood home deterioration, it was redheaded Gwen who wanted action. Don tried to hold on. It was during this unsteady time that he turned to psychiatry for help and talked Gwen into it, too. He took Gwen with him to England and Scotland on a triumphant personal appearance tour in 1951 and tried to turn it into a second honeymoon with excursions, sightseeing and fun between bookings. Back home the trouble started all over again, ending in final separation and divorce.

But until their happiness curdled hopelessly, two significant things about Donald O’Connor stood out. He wanted, needed and appreciated a home and home life. And he’s strictly a one-woman man.

While he was married, Don never looked at another girl. He had tumbled for Gwen Carter in the Paramount commissary when he was thirteen and clowning with Bing Crosby in Sing You Sinners. After he married Gwen, when both were in their teens, he brushed against cuties in the highly emotional business of acting—as all young male stars do—who were more than willing. But extra-marital scandals never touched his name.

And if Don fell short of perfection as husband—as he admits he did—it was not because he neglected his home. On the contrary, Gwen’s complaints were that he liked it too much ever to change the scenery. One maid they had occasionally grumbled because there wasn’t enough excitement around the place to keep her job interesting. But for Don O’Connor there always was plenty, although not in the way she meant. Gwen cooked up the parties and entertainment. Don’s idea of heaven was to install a pool, a home-made bowling alley, to decorate and fix up the place every year, crowd it with playthings for Donna—and dogs.

Even after it was no longer his home. Don returned often to pick up Donna, chat with Gwen—and look wistfully around the place. The house is Gwen’s now, of course, and since she has become Mrs. Dan Dailey she probably will sell it and Don will see it no more. But anyone who knows him is certain he never will be content until he finds another like it—and someone to live in it with him.

“The plain truth is, busy as he is, Don’s, lonely,” says one close friend. “Remember, he’s been a married man all his adult life—and before. Did you ever see a once-happy husband who didn’t try it again as fast as he could? I don’t say he’s in love. But you can bet your roll he’ll be a bridegroom before many months—especially since Gwen is finally out of the picture.”

And Don himself backs this up, laconically but definitely. “Sure, I’ll get married again,” he says. “I fully intend to.”

If and when Don takes that step what are his chances for finding happiness and making it stick on the second try? That depends on the girl he picks, of course—but just as much on Donald O’Connor.

As marriage material, Don has his credits and his debits, like everyone else. In some respects he has changed—in others he’s the same as he always was.

Physically, Don has hardly altered at all. He’ll be thirty on August 28 but he could still pass for a college boy. He has all his thick, wavy hair and even teeth. There are no crowsfeet around his keen blue eyes and he walks as straight as a cadet. Down now to 138 from 160, which he considers his best weight, Don keeps in trim working out in a gym and resolutely working in all the sports interests that intrigue him, such as skiing, golf, tennis, boxing and horseback riding. This last led to the only serious illness outside of measles he’s had in his life, a case of rare “Q” fever which, press agents have gagged, he caught from Francis the Mule, close to the truth but not close enough. Actually the strange malady, which comes from horses, was picked up at a Las Vegas stable. It turned into pneumonia, sent him to the hospital and brought on the most bitter career disappointment in his life when Danny Kaye took over his part in White Christmas with Don’s old pal, Bing. Don is over the fever, if not the disappointment, and left with only a lingering tendency toward colds. And he is making up for the missed session with Bing in Anything Goes.

Financially, too, Don is in the best shape he’s ever been. With his TV show, contracts at two studios and all those sidelines, he faces a golden future which Bing Crosby, for one, believes, “can go on forever.” True, Don will keep less than ten cents on each of those million bucks he may drag in this year and out of that come heavy responsibilities. Since becoming the financial responsibility of Dan Dailey, Gwen may take less of a cut of his earnings. But Don is generous with his relatives, and he’ll always provide for Donna, now a third-grader at the Buckley School and a prize dancing pupil of brother Jack’s.

Don’s fiscal attitudes have improved with his multiple business responsibilities and good advice. The old cavalier approach to his income which naively forgot the taxes is gone. He has worked that off with the help of his hard-headed attorney, Louis Blau. Don still has expensive tastes but he doesn’t toss around his money and he gambles only moderately.

In sum, Don can very well afford to support a wife.

But while that’s important, marriage isn’t all a matter of balancing income and outgo. Temperament, personal habits and emotional patterns which reach way back and seldom change, are even more vital, as is disastrously demonstrated in Hollywood and elsewhere every day. Even the people who know him best disagree as to Don O’Connor’s basic character. “Don’s really a tragedian wearing the mask of a clown,” believes his sidekick, Sid Miller, which is another way of saying he’s Irish. His wife Gwen, who found it impossible to live with O’Connor, still calls him “the greatest guy in the world.” And his niece Patti, only three years younger and more like his sister, says, “Don’s a pixie—he used to shoot me with BB guns.” But in the next breath she states, “Actually he’s a sophisticate.”

Don seems to be all of these and more. He’s well traveled. Despite a skimpy education, his grammar is faultless, his reading deep. He’s a connoisseur of art, he speaks a smattering of Spanish, Italian, French and Yiddish.

Yet, outside his office at General Service, where he’s a show business tycoon, there’s a square of cement with the ragged autograph, “DONALD O’CONNOR,” scratched there as any ten-year-old would scratch it. Don couldn’t resist when the stuff was fresh. He succumbs periodically to other impulses quite as junior grade.

Don and his stand-in, Ralph Grosch, wandered over to the Désirée set to catch Marlon Brando and Jean Simmons in a Napoleonic clinch. At the stage door a cop asked for a pass and Don told his name. The cop shook his head skeptically and anyway which one was Donald O’Connor? Don pointed to Ralph, “He is.”

“You don’t look like Donald O’Connor,” objected the guard. Ralph said that’s just who he was, and the cop boiled, “Look here. How did you boys get in here?”

“We climbed over the fence,” allowed Don.

“Well, you can get into a lot of trouble that way,” he was told. “Now beat it.”

Such caprices well up out of Don O’Connor’s puckish, quick-change past as do his notoriously vague conceptions of time and place. For a while he was so vague about appointments that his publicist, Glenn Rose, although he was an old friend, refused to handle him on the valid excuse that he was ruining Glenn’s relations with the press. That rift was patched on Don’s promise to reform and today he says, “I’ve improved.” Yet not too long ago Don raced feverishly off to play a benefit in a California city, arrived on time by seconds—only to discover the event was the following week. He always has to buy new shoes and rent clubs when he plays golf—although he owns twelve pairs of shoes and two sets of clubs.

Balancing this are some solid adult virtues and habits that make Don a prize in any girl’s hope chest. He has intense loyalty, as proved by all the vintage pals who work for him. He has absolutely no jealousy, as testified by the dozens he’s lifted up the ladder with him, often in direct competition. And his temper is lamb-like.

It’s significant that none of the usual slambang Hollywood domestic battles were aired when Gwen secured her divorce. “When Don gets mad,” his friend Sid says, “usually all he does is turn pale and quiet. Disharmony actually makes him ill.”

Besides a smooth disposition, Don packs few irritating personal habits likely to blow up household storms. He’s as tidy as a racoon and always looks as if he’d just stepped out of a shower, which usually he has. A Sunday job he likes is shining all his shoes and lining them up across the kitchen floor. Don’s biggest extravagance is clothes, which he buys in “hunks,” custom tailored by Devore’s of Beverly Hills at $200 apiece. But for all the things he buys for himself he gives twice as much to others, being generous to a fault. And he’ll eat anything. About the only valid complaint, in fact, that a housemate could make is Don’s disdain of time, his habit of reading until all hours or listening to records twenty-six hours at a stretch. As a dad, of course, he’s real gone. “Donna,” he has said, time and again, “is really what I live for.”

But precious as she is, there’s a lot more than a darling daughter for Donald O’Connor to live for and a Jot left of life for him to make meaningful and enriching to his private existence, so aimless today. Being born and bred in show business, that still and ever will come first in his time and attention, and he’s terribly ambitious to do a dozen things he hasn’t yet done. Television has given Don the long-sought chance to produce, write and direct, and after getting Francis through the Navy he’ll stick to the big league movies where his sophisticated talents get the best showcase. That means he’ll be busy. Maybe, as he says, “too busy.”

After the TV season winds up and Anything Goes is safe in the can Don has a project. For years he’s been cooking an idea to shoot a tragicomic tale of a Pagliacci-type clown in Europe with authentic backgrounds. So this year, he’ll go abroad for a couple of months hunting locations. Meanwhile, he’s hunting a house in Bel Air—and a new car. The house will be, he swears, “a big, roomy colonial that looks like a home.” And the car—well, it was to have been a sporty Mercedes-Benz, but curiously at the last minute Don changed his mind. He ordered a Cadillac, the first big car he’s had in years. “I don’t want to drive around all by myself any more,” he admits. “I like company with me. you need a family-type car for that.”

These are slim straws in the wind, of course. But puffing them along is a need and a hope, shared by all Don O’Connor’s well-wishing Hollywood friends who hate to see him dangling around without the happiness he deserves. The hope, of course, is that before very long another O’Connor will suddenly show up smiling with the right girl and a license for a second try.

THE END

—BY JACK WADE

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE MAY 1955