They Got The Breaks — Now They’re Breaking Hollywood

Liz Taylor and Richard Burton’s romance added millions to Cleopatra costs. Marlon Brando’s temperament made Mutiny On The Bounty second most costly film in history. Marilyn’s contrariness caused 20th Century to blow $2,000,000.

DURING the past few months it has become increasingly evident to anyone capable of reading the newspapers that many of Hollywood’s biggest and highest paid stars are getting much too big for their britches. With mounting amazement the public has learned:

1- That Elizabeth Taylor’s recurring illnesses, willful absenteeism and hectic private love-life are responsible for much of the $32 million spent to date on “Cleopatra,” making it the costliest spectacular in film history;

2- That Marlon Brando’s temperamental tantrums have cost MGM at least $6 million — and turned “Mutinty on the Bounty,” at an estimated cost of about $27 million, into the second most expensive opus in film history;

3- That Marilyn Monroe has been goofing off on the job so consistently that her studio finally had to fire her and shelve the production of “Something’s Got to Give,” taking a licking to the tune of about $2 million.

Taylor, Brando and Monroe of course are top names in the movie business. For one day’s labor before the cameras, Liz gets $10,000—almost twice as much as the average working stiff in this country earns every year. Marlon demands and gets more than a million bucks per picture—about ten times the annual take- home pay of the President of the U.S. And Marilyn’s paycheck ‘is equally astronomical.

Now you’d think that for this kind of dough they would buckle down and turn in an honest day’s work. So what happened?

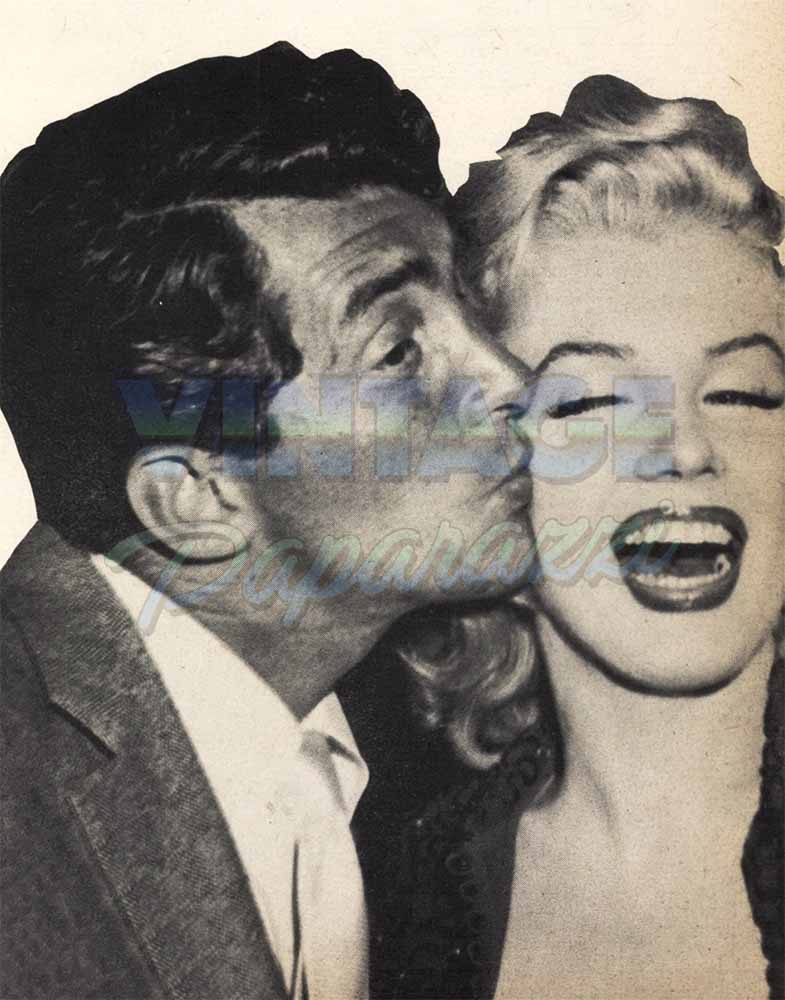

During the seven weeks of shooting on “Something’s Got to Give,” Marilyn Monroe showed up for work exactly five days. And when she did manage to get to the set she was invariably late, tying up the entire cast and a high-priced camera crew.

“If we had continued at the rate we were going with Marilyn,” a spokesman for 20th Century-Fox explained, “we would have had another ‘Cleopatra’. It’s better to shut down and lose $2 million than keep on and maybe lose $10 million or $12 million.”

This is by no means the first time Marilyn has had trouble with her studio. Objecting to the roles as- signed her, she has refused several times to fulfill her contract and took a suspension—once for more than a year. She finally had to be mollified by an under-the-table payment of $450,000 to keep her happy.

GETTİNG to the studio late, or not at all, has become a habit with her. After directing Monroe in “River of No Return,” Otto Preminger swore he’d never do another film with her. “She was always 45 minutes to two hours late.” Billy Wilder, who directed her in “Seven Year Itch” and “Some Like It Hot,” said that extracting a performance from her was like “pulling teeth.” He explained:

“She has breasts like granite, and a brain like Swiss cheese . . . full of holes. She defies gravity. She hasn’t the vaguest conception of the time of day. She arrives late and tells you she couldn’t find the studio, though she’s been working there for years.”

On the set she acts like a prima donna. In “Bus Stop,” for instance, she objected to Hope Lange’s blonde hair because it conflicted with hers. When director Joshua Logan refused to have Miss Lange’s hair darkened, Marilyn walked off the set and tied up the whole production until the director gave in to her demands.

As a rule she is heartily disliked by other actors. After making “Some Like It Hot,” Tony Curtis refused to work with her again. “She is a most unpleasant dame to get along with,” he said. “She’s suspicious of other actors, constantly tries to stir up trouble between them.”

And how was it making love to Marilyn?

“It was like kissing Hitler!” Tony snapped.

When it comes to behaving like a spoiled brat—on and off the stage—Liz Taylor can give Monroe cards and spades and still win handily. Whenever she is bored, or her work interferes with her love-life, she simply doesn’t show up on the set.

Several times during the latter part of the filming of “Cleopatra” she failed to appear for a day’s scheduled work, preferring to dally on the beach with her co-star and new boyfriend, Richard Burton. Each time hundreds of extras were given a holiday with full pay—at the studio’s expense.

AFTER pouring enough money into the production to dam the Nile, and winding up with seven hours of unedited film, studio executives heaved a sigh of relief and proclaimed the picture finished. But Liz demurred. She insisted that several more scenes be shot on the isle of Ischia—which would put her back on the payroll for three more weeks at $10,0000 per day, and added a minimum of $400,000 to the already excessive cost of the opus.

Fearing that the three weeks work might cost another $3 million instead of a mere $400,000, studio executives insisted on calling it a day. Whereupon Liz, backed by producer Walter Wanger, threatened to sue 20th Century-Fox. At this writing the battle of words via cable and long-distance telephone continues. Meanwhile Liz and Burton are living it up together at Ischia.

Marlon Brando admittedly is a fine actor and big boxoffice attraction. He also is a born trouble-maker who insists on running the whole show in any film he condescends to make and an old pro at forcing his Hollywood bosses to kowtow to his whims, thereby appreciably upping budget costs.

He refused to sign for “Sayonara” until the ending of the script had been changed “to get a message about tolerance across” — by having the American hero wed the Japanese heroine. Similarly in mid- production he suddenly decided that he didn’t like the ending of “The Young Lions,” refused to finish the film unless and until he could rewrite it. In addition to starring in “One-Eyed Jacks” he directed it, and supervised the writing on the script as well. Although he spent money lavishly on this one-man show, it was a flop.

HOWEVER by all accounts his overwhelming ego, petulance and insufferable conceit has broken all records in filming “Mutiny on the Bounty,” turning it into a producer’s nightmare which to date has cost MGM more than it spent on “Ben Hur” and “Gone With the Wind” combined.

According to the film’s director, veteran Lewis Milestone, “Brando’s recalcitrance, pettishness, argumentativeness and sulking has cost the production at least $6 million in additional cost and months of extra work.” Among his charges:

1- “Whenever I tried to direct Brando in a scene he’d say: “Are you telling me, or asking my advice?” Later he put plugs in his ears so he couldn’t hear the director, or other actors. Finally he quit talking to the director, took to arguing with the producer.

“It wasn’t a movie production, it was a debating society. Brando would discuss for four hours, then we’d shoot for an hour to get in a two-minute scene. By now he was directing himself and ignoring everybody else. It was as if we were making two different pictures.”

2- He kept insisting on changes in the script. After six different writers had tried their hand at it he was still dissatisfied, insisted on rewriting the ending himself “to get across a message.” The ending he wrote was awful, the producer rejected it and eventually they went back to the last version.

3- “To find his leading lady, Brando took each of 16 pre-chosen Polynesian maidens into a room with him, one at a time, and threatened to throw himself out of the window in order to study their reactions. Since all responded with giggles, this procedure was unsuccessful. He eventually chose as his co-star a girl named Tarita, who was employed as a dishwasher and waitress at the local hotel.”

4- He spent all of his evenings in Tahiti in local night-spots, playing the native drums and dancing barefoot with Polynesian cuties. Next morning he would arrive on the set bleery-eyed and unprepared for the day’s shooting. He rarely knew his lines, would fumble through as many as 30 takes of a single scene.

5- “Three weeks before we were to leave Tahiti he decided to move from the house we had rented for him to an abandoned villa nearly 50 kilometers (about 30 miles) away. It cost us more than $6,000 to make it habitable for him.”

6- Brando’s contract called for $500,000 advance against 10 per cent of the picture’s gross, with $5,000 overtime for every day the making of the film ran overtime. Before it was finished, he had collected $1,250,000. As Milestone wrily remarked:

Because of those off screen antics of Liz Taylor and Dick Burton, Cleopatra will probably never return investors’ dough.

“This picture should be called ‘The Mutiny of Marlon Brando!’ ”

Though Taylor, Brando and Monroe are the most recent, they are by no means the only temperamental stars in Hollywood to give producers ulcers on their ulcers, drive them to the verge of a mental breakdown and bring the studios to the brink of bankruptcy.

Take Monty Clift, who has been a problem to just about every director, producer and studio with whom he has been associated. While on location in “Raintree County” (which he did with Liz Taylor) he hit the bottle so heavily that postponements of scheduled shooting cost MGM a small fortune.

More recently, while filming “Freud” in Munich, he developed a psychological block and couldn’t remember his lines. Then he suddenly disappeared. Director John Huston finally tracked him down to London. To get the film completed, Huston had to hire a psychiatrist who put Monty under hypnosis, and by use of post-hypnotic suggestion actually succeeded in getting him to remember his lines!

To keep a temperamental star contented and working, the studios often have to go to fantastic lengths in providing such lavish fringe benefits as the best in living quarters, servants, expensive transportation and other tidbits.

A Wad For A Whim

Yul Brynner’s contract for example provides that whenever and wherever he is working, the studio must provide him with a shiny black Cadillac, complete with uniformed chauffeur. When the bald- domed star was on location in Mexico with “The Magnificent Seven,” the studio scoured the country but was unable to come up with a suitable Cadillac. It offered him a brand-new Imperial instead, but he rejected it and refused to go to work until a Cadillac was imported for him, all the way from Hollywood!

Jackie Gleason’s demands are even more astounding, usually occupying numerous pages of any contract he signs.

His contract for “Gigot” specified that a specially-built Rolls Royce would be ready and waiting when he arrived in Paris to make the film. The car was to be finished with 46 coats of opal and burgundy paint (each coat hand-rubbed with loving care). It had to be air-conditioned and equipped with a refrigerator, fully stocked bar, TV set, hi-fi and radio-telephone. The studio had to furnish his chauffeur with a specially designed uniform to match the car, and send him to the Rolls Royce school in London for three weeks where he received special training in driving the car!

The contract also provided that while in Paris he and his numerous entourage would be put up in the fanciest available living quarters. The studio rented the late Aga Khan’s villa in Versailles for him, and redecorated it. He didn’t like it, so he was transferred to the penthouse of the swank King George V Hotel. In order to make room for him, a Texas oil millionaire was persuaded to move out. Gleason’s hotel bill alone amounted to over $60,000.

An avid devotee of Dixieland, Gleason insisted that the studio also provide him with a private Dixieland band to play for him whenever he was in the mood for music, day or night. It cost the company $1,000 per week to provide him with the band, but he got it!

All of which brings up a very pregnant question: who’s the boss in Hollywood these days, the studios or the stars?

The inside story is, movie moguls have suddenly discovered that in promoting the star system they have created a Frankenstein which is driving the entire film industry into bankruptcy. And today they are girding their loins for a battle which may well determine the entire future of the industry in this country.

The opening guns of that battle went off recently when 20th Century-Fox, one of the leading proponents of that system, fired Marilyn Monroe and sued her for $500,000 for breach of contract because of her performance (or rather non-performance) in “Something’s Got to Give.”

Equally significant was the forced resignation of Spyros Skouras as president of the same studio, a few days later. It was Skouras, more than any other individual in movie-land, who is responsible for the terrific buildup given such stars as Marilyn Monroe and Liz Taylor.

It’s Gotta Stop

Sure enough, something’s got to give, and the industry is determined it will be the spoiled brats it has pampered for so long because it was running scared of the burgeoning TV interests.

Typical of the New Look in the film Capital is the comment by producer – director Robert Wise, in a recent interview with a national magazine:

“I think the ‘Mutiny on the Bounty’ problems with Brando, plus the problems with Elizabeth Taylor in ‘Cleopatra,’ may well make the end of the star system as it exists in Hollywood today. The big-star monopoly—the monster that we ourselves have created out of our fear of television—has now become such an expensive luxury loaded with trouble that it’s just not worth it.

“I for one am discarding it. I am doing my next two films on modest budgets with no stars whatsoever. I think this is the new pattern for the industry — a turning point for all of us. More and more of us are saying, ‘The hell with the star, I’ll make little black – and – white pictures with good scripts and unknown actors.’

“We must do that to survive. A few more mutinies by stars and we’ll all be out of business.”

If his prediction comes true, the Hollywood heavens will soon be full of falling stars.

—By BRAD ECKHARDT

It is a quote. Inside Story MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1962