Robert Conrad’s Own Story

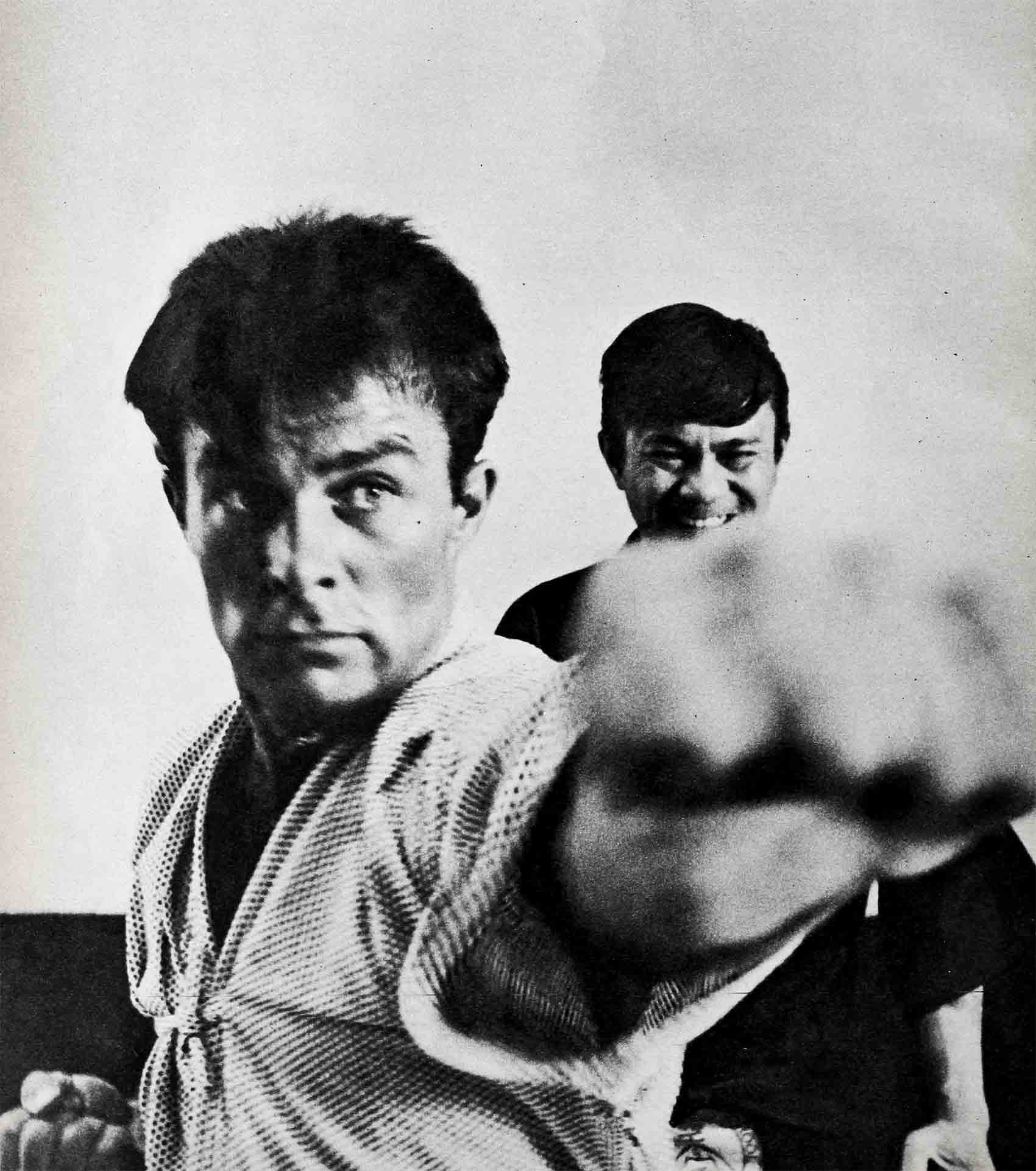

“My body is a deadly weapon,” Bob Conrad said. “With two fingers I can blind a man. With one hand I can paralyze his arm. With a single, well-placed blow I can kill him.” As he talked, Bob demonstrated, moving from chair to desk and back again, his lean, hard body as graceful and as deadly as a panther’s. I felt as though we were in a jungle.

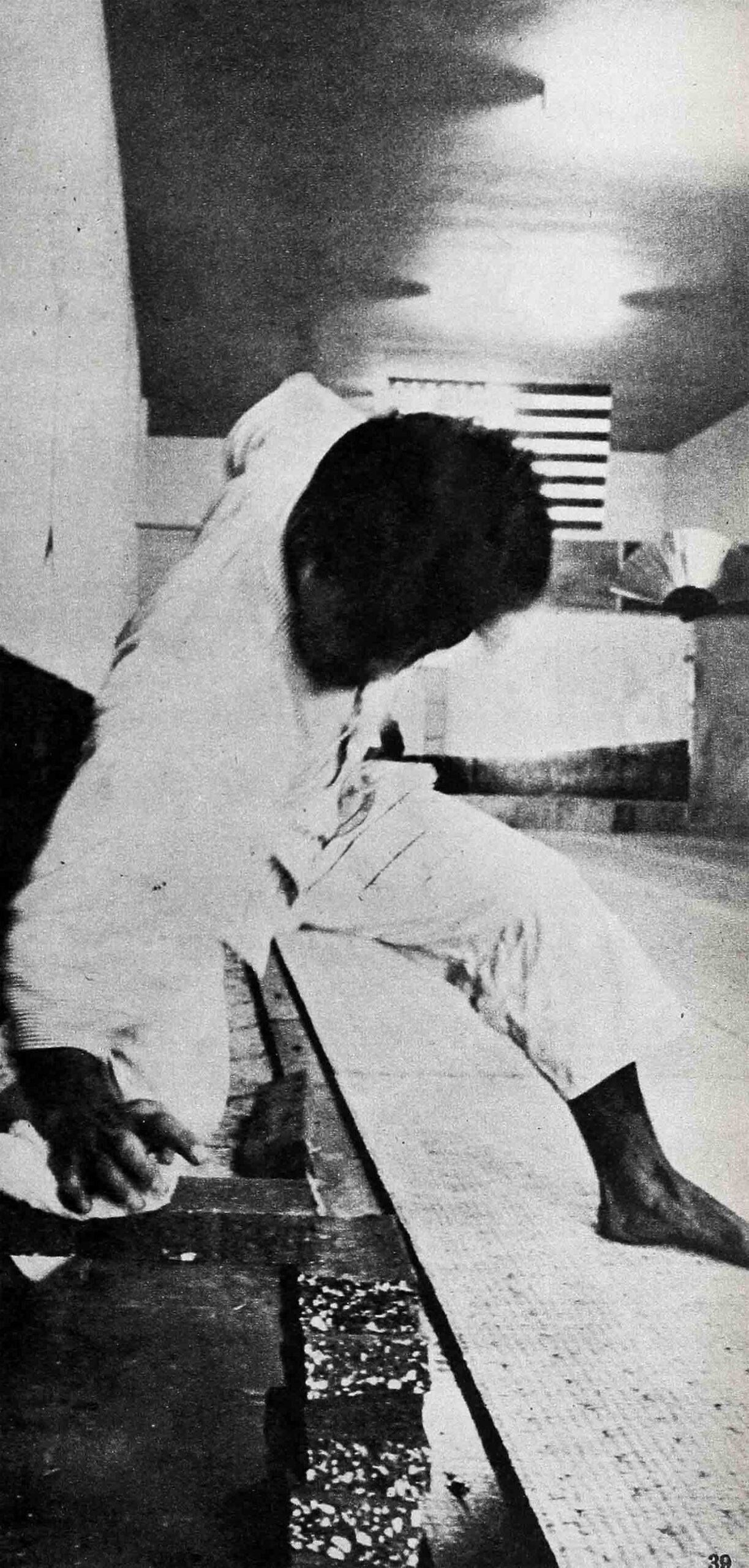

“Some people think that my studying karate is a kind of joke, a game.” He stopped his pantomime. Facing me, he flexed his knees, leaned back from the hips and raised his arms oddly. “Try holding a position like this for a couple of hours—especially when you’re already bone-weary from work, when every minute you spend at it is stolen from your family or from the sleep you need. When you’re done, you ache in muscles you never knew you had. And what can you show for it? Nothing but your stiff back and the knowledge that your teacher, a man six inches shorter and thirty pounds lighter than you are, can destroy you in seconds. And for months you may never learn his skill because he’s testing you, making sure you’re ready.

“ Karate turns a man into a loaded gun, and no one puts a loaded gun into the hands of a child. I had to show my teacher that I’m worthy of knowing karate—and that means passing inspection on my mind, my heart, my soul. . . .”

“Why bother?” I asked.

Bob stopped. “What?”

“Why bother?” I repeated. “To hear you tell it, learning karate is an all-consuming task. I don’t understand why you’d want to take the time.”

“I see.” Bob thought for a moment. Then, lightly, he said, “I’m learning it . . . because I might use it.”

He said it too casually. “Use it? You mean in a fight? Do you get into fights?”

“As a matter of fact,” Bob said, “I do. The last one I had before I started karate was in a restaurant in Beverly Hills. I was sitting with friends when a drunk came over. He was about six-two, maybe two-hundred-thirty pounds. That’s four inches taller and seventy pounds heavier than me. He stood over me and made a crack. I got up and the next thing I knew we were finishing it in the alley. I got a black neck and he got a bloody nose.

“If I’d known karate he would never have touched me. Instead of staring at his stupid face. I’d have been looking at his weapons—his hands and his feet. Since his feet weren’t in position, I’d have concentrated on his hands. I’d have parried his blow and paralyzed his arm in the process. Then I’d have quieted him with a two-knuckle punch to one of the vulnerable areas—ribs, groin, the back of the head. In this case, considering the position and his size, probably the groin. He would never have had a chance.”

He acted the whole thing out, his hands moving swiftly through the air. “I’d have saved plenty of wear and tear on myself. But, as it was . . .”

“As it was,” I finished for him, “you were lucky to get off as well as you did.”

He stared at me. “Well, I wouldn’t go that far,” he said. “I can take care of myself. I’m a pretty good boxer, have been since high school. And I’m powerful. I lift weights. If two guys should jump me, I’d be in trouble—but that doesn’t happen ever day. Besides, I’m a peaceable sort of guy. I dislike violence.”

A “loaded gun”

“But you’re a loaded gun,” I said.

Bob shrugged. “A loaded gun doesn’t have to go off. I’ll probably never use f karate. I don’t have any reason to. The guy who got me interested in it, he’s a Hawaiian who works nights as a policeman in Malibu, uses it to subdue violent kooks. He’s assigned to the psycho division. But me—I’ll never use it.”

“Now, wait a minute!” I said. “Five minutes ago you told me you learned karate because you might use it. Now you say you’ll never use it.”

Bob sat down and passed a hand through his hair. “I said that, huh?”

I nodded.

“Well, I guess that’s not my reason. I guess the real reason I work at karate is because it’s a challenge.”

“A challenge,” I repeated. “But so is becoming a nuclear physicist. Why should you want to know how to kill a man with your bare hands?”

For a long moment we stared at each other. “I guess,” he said at last, almost lost in thought, “I guess you could say it’s because of the gold braid.”

I could see he had become immersed in thought. I didn’t want to interrupt. I just let him talk.

He stared at the floor, and the words came, slowly. “I won the gold braid when I was a kid, and then—suddenly—I lost it. I haven’t thought about it for years, but . . . it meant so much to me once.”

Suddenly, the words began to come rapidly. Bob seemed to have forgotten that I was there, forgotten that my pencil was recording what he said. As I listened and wrote, a whole new world opened before my eyes—Bob’s world. I had never heard him speak of it before, and yet this was the world in which he had grown up, the world that had formed him.

He was seven years old when he entered that world, a frightened little boy clinging to his mother’s skirt. What is it psychologists say about the children of divorce? That no matter how gently and thoroughly the divorce is explained, the child invariably feels that he alone is responsible—that some failure on his own part drove one parent away. That the child feels in his heart he is unworthy.

Bob Conrad was such a child. “I stayed close to Mama’s hip,” he said. And it was true. Perhaps he was afraid to venture away lest the world discovered his unworthiness; or perhaps he was afraid that if he should stray, his mother, too, would be gone when he returned. Perhaps that was why Bob’s mother took such a drastic step—literally thrust him away from her—to force him out into the world.

She sent him to military school.

The first sight of the school was terrifying to seven-year-old eyes. The vast parade ground. The echoing dining hall. The tall male teachers. (Would they, like his father, reject him?) The straight rows of boys in their identical uniforms, their identical faces looking neither to the left nor right. Of course, a boy might hide behind his uniform, living unnoticed in the crowd, existing only for visiting days and the escape of vacations.

“You have to fight . . .”

But that hope was soon dashed. The retired colonel who was head of the school stood before the new boys. His body was erect, his voice strong.

This is a boy’s world, he told them. Your world. Here, you’ll learn to make the most of yourself, and we’ll help you to do just that. But never forget this: Our school is like the world outside. You have to fight to get ahead. Some of you have natural ability. That will help. You’ll only have to fight the competition. Others of you will have to fight yourselves as well. That’s harder, but it’s not impossible. No matter how hard things get, keep fighting. Keep competing. There are only two kinds of people in this world—those who succeed and those who fail. Only you can decide your destiny. The choice is yours.

The choice is yours.

It was terrifying. It was his deepest need, brought out into the open, shaped into a way of life. Test yourself. Prove yourself. If you think you’re unworthy—fight, win, prove that you’re worthy after all.

There are two areas, the colonel continued, in which a boy can excel. One is physical. Be strong. Be quick. Good at games, accurate on parade. The other is mental. Be sharp. Learn fast. Make good grades. Stretch your mind. For those few boys who can excel in both areas, there is the gold braid. The boy who earns the right to wear the gold braid never gets a grade under ninety. He makes that grade in every subject—physical and mental. The boy who wears the gold braid—and only a few of you will—can be sure that he has reached the top.

Bob Conrad, seven years old, had to make his choice early. He could hang back, avoid testing himself. His quick mind and agile body would place him on the middle rungs without difficulty. He was tempted. It was safe.

But the gold braid hung before him, a vision, a dream. To try for it and fail would be a disaster. But if he won—if he won . . .

He accepted the challenge. He went after the braid.

His naturally quick mind proved an immediate handicap—he was placed in a class with boys one year his senior. And in childhood a year is a terrible edge. His classmates had had one more year of reading, schooling, living, behind them.

He was at a disadvantage physically as well. His body was agile, but it was not tall. Not tall enough for the easy, leaping, one-armed basketball shots. Not tall enough for the effortless base-running of his longer-legged classmates. Instead there were hours of back-breaking, heartbreaking, muscle-stretching workouts to build his slender body into a hard, efficient tool. Hours more of study, reading, catching up and forging ahead to reach the top of his class.

And as he struggled, the gold braid danced before his eyes. He had gambled his self-respect, almost his very life, on his ability to win it. As the time passed, his body grew taut and strong and his mind not only quick but retentive.

At the end of the year he got his grades. Trembling, he read them, one by one.

They were all over ninety percent.

He had won.

He wore the gold braid. Now he was somebody; now he had proved himself. He need never fear again. The braid, the glory, was his.

But winning the braid was one thing; keeping it was another. Now he was marked as the boy to beat. As his classmates struggled to outdo him, Bob had to keep fighting to stay ahead. He went out for sports that heavier boys wisely avoided. He studied far into the night and fell asleep over his books—to dream that they had ripped the gold braid from his shoulder. He woke and studied again.

Always the colonel was there, to encourage, to help, sometimes to prod. “Robert, I was looking over the week’s grades. Some of them are better than yours. You’d better work harder.”

Bob did and he was happy, gloriously happy. Knowing he was top boy, he could enjoy the laughter, the games, the brisk air during early morning drill, the mind-stirring thrill of learning. Years went by and he became confident, sure of himself, at ease with the world. The gold braid gleamed on his uniform.

Then, when he was thirteen years old, his world widened. He discovered girls. At invitations from girls’ schools nearby, the older boys in dress uniforms climbed into buses, were taken to tea dances.

At first Bob was shy. But soon his feet found the rhythm of the music. He discovered he loved dancing. It was marvelous. If you had to ask a girl in order to enjoy it, then so be it. After a while, holding a nervous female in his arms became less of a necessary evil than a real pleasure. Here was a breed shorter than he—his chin rested comfortably on blond curls. Here were shy smiles and admiring glances and awed voices asking him the meaning of the gold braid he wore, gasping reverently when told.

He liked girls.

Now he woke at night from dreams of silky dresses—and thought of the next dance.

For six months he lived in a perfumed world of girls.

And they took the braid away!

He had lost it—lost it—lost it !

The colonel looked at him with disappointed eyes. His friends tried not to stare at the bare spot on his uniform. His mother told him it didn’t matter, he was leaving anyway at the end of the year.

But the world had crumbled around him. He had climbed to the heights and fallen. He had tasted success and let it slip away. He was destroyed.

He graduated without the braid.

For the second time he was faced with the harsh necessity of making a choice. He could accept defeat. He could go on to a co-ed school and accept with grace what was available to any boy—fun, kicks, girls. Or he could try again.

He chose to go to another all-boy school and to try again. Doggedly he went after every honor. Day after day he tested himself. Was he doing his best? Was his best good enough? Was anyone doing better? Were there new worlds to conquer?

Years went by. He forgot that the gold braid had ever existed. But the drive toward the top never eased. Many times the prize changed form, changed name—but what drove him on remained the urgent, unconquerable need to be best, to reach the top. The choice is yours, he had been told. And he never forgot it.

Bob Conrad could choose only the best, the rarest, the thing that few other men could have, or be, or attain.

He married a beautiful, brilliant, cultured girl—no other could possibly do. He chose a career that combined talent, skill, physical strength and good looks—acting required the use of the whole man. He reached out aggressively towards goals other men only dreamed about: “I’m going to be a rich man—I’m planning on it.” When he learned that his wife would inherit a fortune on her thirtieth birthday, he shrugged it off. “It’s nice, but it hasn’t anything to do with my getting rich. I didn’t earn that money. I’m going to make a pile myself .” He worked constantly, intensely at his acting; asking to have his scripts made harder, more demanding; insisting that every new skill he acquired be written into his part.

And every success meant only one thing.

“The gold braid,” Bob Conrad said softly, still speaking more to himself than to me. “Now I see it. They’re all—all the gold braid.”

And karate was the last of them.

I saw now why Bob Conrad had found karate so irresistible. The very difficulty of learning karate—the back-breaking exercises, the anatomy charts to be studied, the Oriental philosophy to be absorbed, the psychology of violence to be analyzed, made the challenge more tempting, insured that only the best would succeed.

And yet—however rich and famous he became, whatever rewards were heaped upon him, I knew he could never recapture completely the pride of the child with the gold braid glowing on his shoulder. However successful and happy he became, he would never wipe out entirely the memory of the day the shining symbol was torn away.

But does it matter? I think not. What matters is the spur that still drives him on, the vision that still dances before his eyes. What matters is the hidden secret of the gold braid—that in the end there is something more important than the braid:

The struggle to attain it.

THE END

—BY JAY RICHARDS

Bob stars on “Hawaiian Eye,” ABC-TV, every Wednesday from 9-10 P.M. EDT.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JULY 1962