Sophia Loren Faces Five Years In Jail

The shrill brrrrrrrr-ing does not stop. Brrrrrrrr-ing. Brrrrrrrr-ing. Brrrrrrrr-ing. Sophia Loren, her eyes still shut, reaches out for the alarm clock on her night table, turns it off and then buries her head under the pillow. But the bell still rings and, swimming up out of sleep, she knows—it’s the phone.

The phone? Oh no, it can’t be! She’d given strict orders not to allow any calls through, she isn’t due at the studio until noon, and here it is—a look at the clock—only 7 A.M.

Brrrrrrrr-ing. Her greenish-gold eyes narrow to slits as she stares at the phone. Every time it’s rung, lately—every time she’s picked it up and listened—there’s been bad news on the other end. This phone in the Milan hotel is just like all those others, except that this one is brown and ugly, while those others were pink and ugly, or white and ugly or black and ugly. All ugly, and all with this shrill, incessant brrrrrrrrr-ing! But she is being silly. Maybe the switchboard operator is calling her by mistake. Or—or maybe something has happened to Carlo! She grabs the phone now, and it is Carlo—they are going to put him on—but why so early? It may be the middle of the afternoon in New York, where he is, but Carlo knows it is only 7 A.M. here in Milan. It must be very urgent.

Ah, now Carlo is on. He is disturbed. He tries to conceal it, but as usual he is a bad actor. He blurts the whole of it out . . . jail . . . five years.

In swift Italian, Sophia tries to re- assure him—and reassure herself. But Carlo gives her the details; the American newspapers, he says, are full of details about the bigamy charges that have just been launched against the two of them in Rome. One paper quotes the Italian government as stating, “The movie producer Ponti and Academy Award winner Sophia Loren must stand trial in Rome for bigamy.” Another paper spells out the possible penalty if they are found guilty: “Under Article 566 of the Italian penal code, Mr. Ponti could face a jail term of five years if convicted of bigamy. Miss Loren could face the same on conviction of being a party to bigamy.” Then Carlo tells her—there is an American newspaperman outside the phone booth, Earl Wilson—very simpatico—who would like to speak to her if she doesn’t mind. She says it would be all right. Wilson asks her reactions to the bigamy charges. “I hadn’t heard about it,” she says. “. . . of course, it’s not a nice thing . . . but I am guilty with him if he is guilty. Whatever happens, it makes no difference.”

Carlo takes the phone and he and Sophia discuss many things, including the possibility of “changing“ nationality to escape jail if convicted of the bigamy charges.

Carlo turns to Wilson but still speaks into the mouthpiece so that Sophia can also hear him. “I’d even be willing to become a Russian to stay with Sophia.”

Sophia’s own words come back clear and quick. “Even if I became a Japanese, I’d still feel I was a Neapolitan.”

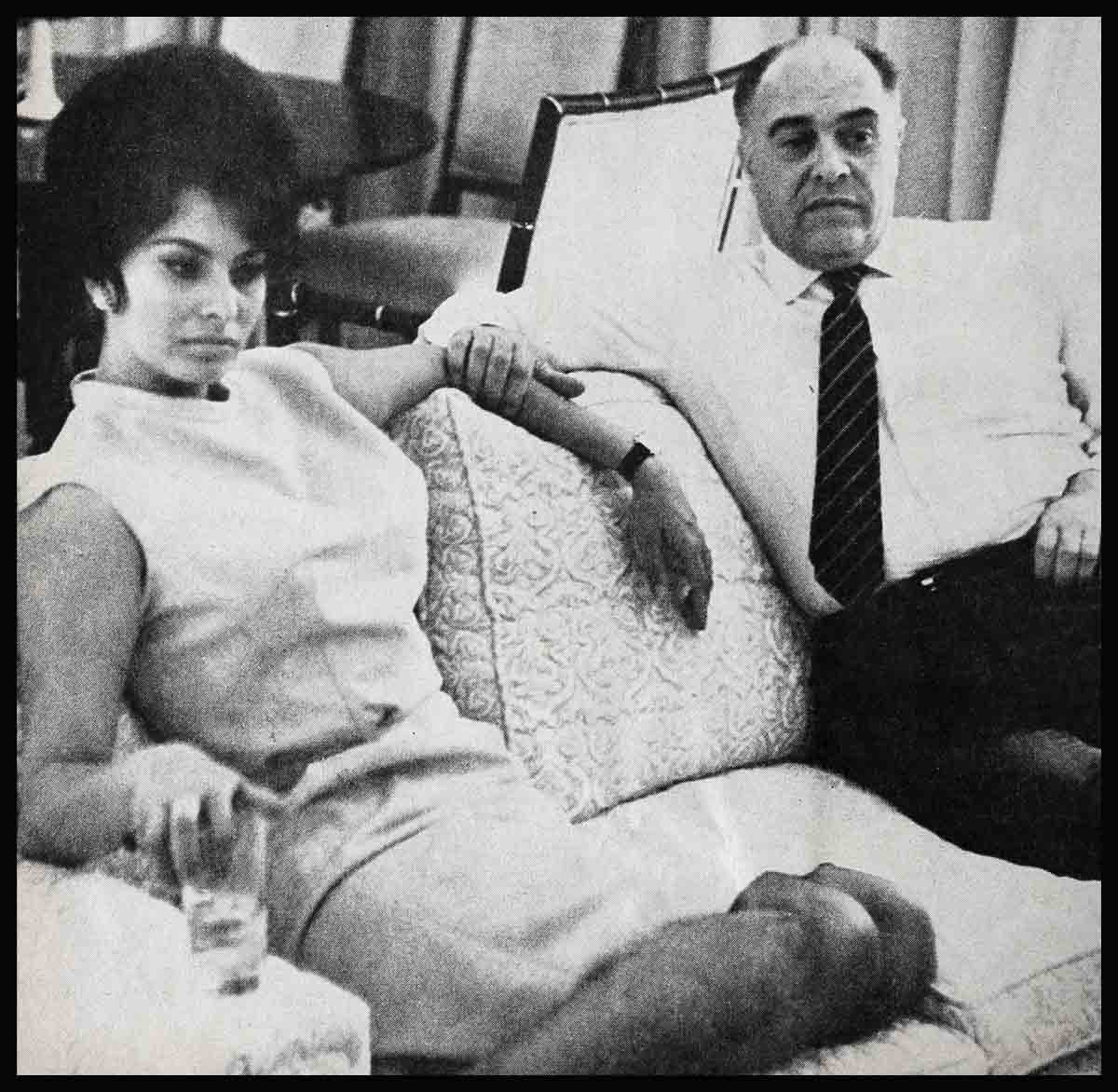

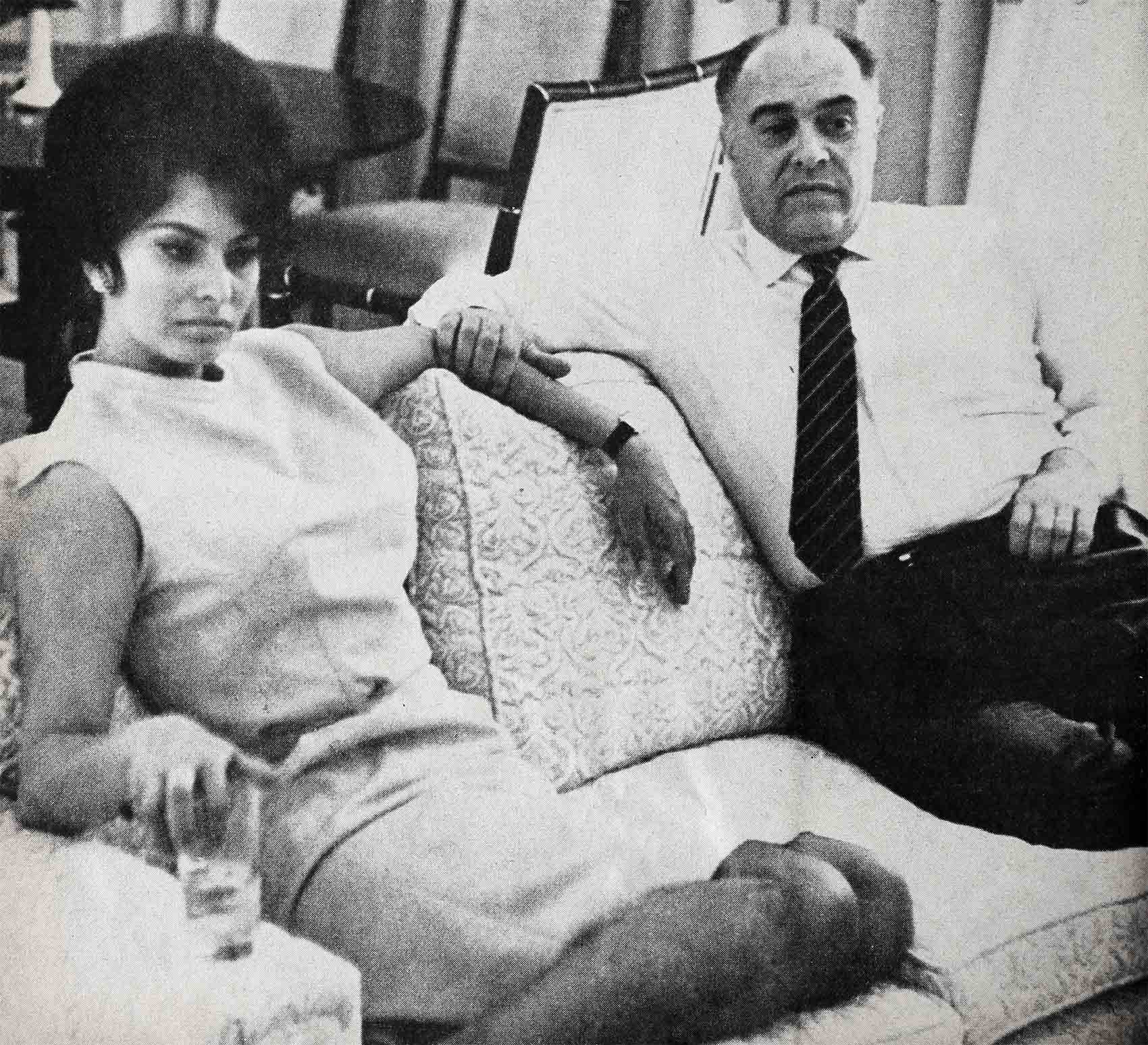

The reporter closes the door of the booth to allow the Pontis the privacy of husband-wife talk. Through the glass, the pudgy, baldheaded man can be seen listening to what Sophia is saying. When he hangs up the receiver he is smiling.

But in the Milan hotel room, Sophia is not smiling as she slips the telephone back into its cradle. Tears creep down her cheeks. She thrusts her long fingers into her reddish-brown hair as if to yank it out by the roots. She stares with hatred at the ugly phone.

Once, long ago, before she and Carlo were married, when she knew nothing about art and literature and music—and yearned to know everything—they had gone to an exhibition of Dali paintings. In many of the pictures the main object was a telephone. When she asked Carlo why the artist had put phones in so many canvases, he said something about an “obsessive symbol“ and that Dali probably had nightmares in which telephone cords were strangling him.

She hadn’t quite understood what an “obsessive symbol” was, but she’d laughed out loud at the thought of anyone being afraid of a telephone. But now she knew! Ever since a month before last Christmas, she knew deep in her body where all true knowledge lies.

Brrrrrrrr-ing. It is October, and she is on the floor of a room in Rome, surrounded by one hundred red roses. It is her twenty-seventh birthday. The roses are a present from Carlo, the sapphire-and-diamond ring on the third finger of her left hand is a present from Carlo, the phone—that’s probably Carlo at the other end of the line.

She rises gracefully to her feet and moves across the room, her figure molded into the simple red dress that caresses it. The corners of her vivid, red-painted lips curl upward in a smile, exposing her white, spade-shaped teeth, as she listens.

A second goes by, two seconds. The corners of her lips droop slowly, closing a curtain over her smile. Later, when she walks back across the room, her body fights with her dress as if it were about to explode. Suddenly, her feet are too big, her nose is too long, her mouth is too large, her forehead is too low, her hands are too huge, her figure is too cumbersome. And when she speaks at last, her voice sheds the tears she keeps from her eyes.

“Today, Carlo and I are no longer married,” she says, and twists the sapphire-and-diamond ring until her ring-finger drains white. “We live together, of course, but we are not married. We had to—we had to annul our marriage, because Italian law does not recognize Carlo’s Mexican divorce from his first wife—and therefore, in Italian eyes, we were bigamously married.”

She twists the ring around from the inside of her finger to the outside so that it is right in place where a wedding ring—if it were a wedding ring—should be. “It is a nuisance,” she continues, “but it does not worry me too much. I feel married—that is the important thing. Only in one respect is it frustrating. I want to have a child. Not being legally married makes it complicated. Carlo would have to get his first wife’s permission to pass on his name to our child. I do not want to start a child with paper-work.”

No one questions Sophia as to whether the annulment has really gone through or not. No one asks her why the news hasn’t been released to the newspapers. It is her birthday, and soon it will be Christmas; it just isn’t the time to ask a woman who is trying to adjust to not being married whether she might actually still be married after all—and therefore still vulnerable to prosecution for consorting with a bigamist. Or, worse, to point out that if, in fact, the annulment has gone through and she continues to live with Carlo (as she insists she will), that she will be branded, if not prosecuted, as an adulteress. . . .

Brrrrrrrr-ing. Just before New Year’s. The phone shrills. A lawyer’s voice on the other end. Cool, precise. There’s been a legal setback. The annulment has been held up. Yes, she’s still married to Ponti. No, there’s no guarantee the problem can be settled. . . .

Brrrrrrrr-ing. It’s January. Sophia is in the United States to receive the New York Film Critics Award for her performance as the anguished mother in “Two Women.” A happy occasion. A triumphal moment. But after the ceremony she is called to the telephone and told that Italian authorities have formally requested that she and her husband be brought to trial for bigamy. Because Italy does not recognize the Mexican divorce granted to Ponti, in 1957, from his first wife, Guiliana Fiastri.

When she was presented the Film Critics Award, Sophia had said to me, “I still can’t believe it is being given to me.” Now, after the phone call, she broke down and called the action of the Roman prosecutor “the worst thing that ever happened to me.”

“I love Carlo,” she told me. “We would like to have a normal married life. I would like to have children. But this can not happen yet with this action. Whatever happens, I will remain married to my husband.”

Later she added, “I feel at home with Carlo. It’s not important to marry a handsome man. . . . If you could see Carlo in my eyes, you would find him the Prince Charming. . . .”

Brrrrrrrr-ing. It’s March. Almost time for the wedding, the marriage of Sophia’s sister Maria Scicolone to Romano Mussolini, son of former Italian dictator Benito Mussolini. Sophia is bubbling with excitement. Her only sister is getting married. And when she and Carlo watch Maria and Romano at the altar of the carnation-decked Church of St. Anthony, it will be almost as if the two of them, rather than the youngsters, are wed.

And it won’t be cold and remote like her actual marriage to Carlo had been, back in September, 1957—when lawyers stood in for them at a proxy ceremony in Mexico. She had been in Hollywood and Carlo in Italy, while two men in Mexico mumbled the words that made Carlo Ponti and Sophia Loren man and wife. And the man and wife then had to be notified by telephone that the marriage had taken place.

But now, in the Church at Predappio, it would be different. As the priest said the sacred words for Romano and Maria, in Sophia’s heart, and Carlo’s, he’d be saying the words for them, too.

Brrrrrrrr-ing. She lifts the receiver. No need to be afraid. Everything that could go wrong had already gone wrong. Donna Rachele Mussolini, Benito’s widow, had originally opposed the marriage by saying her son would never marry a “nothing girl” who is “only the sister of her sister, and we all know what her sister is.” But Romano’s mother finally had been won over. Then, there’d been the danger that the authorities might come to the wedding in order to serve a warrant against Sophia in regard to the pending bigamy action. But she’d said, “I have only one sister and I intend to be there for the wedding.” Also, she’d balked at the original plan of holding the ceremony on February 11th, the 33rd anniversary of the signing of the Lateran Treaty by Mussolini with the Vatican. She was afraid the dead dictator’s fanatic followers might attempt to turn the occasion into a Fascist celebration and spoil her sister’s wedding day. So she had insisted on changing to another date, and at last Donna Rachele had agreed.

Now, into the telephone, Sophia says, “Yes, si, I understand.” Then hangs up and backs away as if from a poisonous snake. That call—it was to say there’d been a church ruling. Carlo will not be allowed to give the bride in marriage. Carlo will not be permitted even to be present in the church. Because his previous marriage had ended in a foreign divorce. So now she must be at her sister’s wedding without Carlo. And the lovely words will not be for them, after all.

Even at the ceremony, everything goes wrong. Msgr. Giuseppe Bonaccini, the presiding bishop, can’t get into the church for twenty minutes because a crowd of 6,000 persons is milling outside. When he finally squeezes through, he refuses to start until the photographers leave the altar and the front of the church.

As Romano waits for Maria to come down the aisle, he suddenly turns pale, sways back and forth and begins to fall. His two witnesses grab him and drag him into the adjoining parish hall, where a doctor gives him an injection. Then he returns to his place at the altar.

After the hour-long nuptial Mass, the entire crowd of 6,000 friends, photographers, neo-Fascists, film fans, Communist villagers and old-time Black Shirts in the church surge forward to congratulate Maria. Now it is the bride’s turn to faint. Romano sweeps her up in his arms, trying not to crush her white satin gown, and carries her to the parish hall, with her long white veil streaming out behind her. There she is revived.

The crowd follows. Mobs of screaming people crash through 400 police guards and into the parish hall where the reception is being held. Sophia, along with the bridal couple and Donna Rachele, manage to escape through the kitchen door.

Romano and Maria speed off to their honeymoon, while Sophia’s chauffeur-driven, silver Rolls-Royce heads towards the Rome airport where she will board a plane for Paris. About nine miles from Predappio, the Rolls-Royce tries to pass a Fiat going in the same direction. The two cars side-swipe each other, the Fiat swerves and crashes into a motor scooter. Both cars grind to a stop—but it is too late. The driver of the scooter, a school teacher, lies dead in the road.

Brrrrrr-ing. It’s April, 6:30 in the morning. Sophia, in green pajamas, has been awake the long night. With her left hand she grinds her cigarette into an overflowing ashtray; with her right hand she holds the phone so that Carlo can listen in, too.

In perfect synchronization, operators on both sides of the Atlantic—in Hollywood and in Rome—chime, “Congratulations, Sophia—Auguri, Sophia.” She’s won an Oscar! An Academy award for her great role in “Two Women.”

“Mamma mia, mamma mia, mamma mia bella! Ho vinto!” (Dear me, dear me, dear me—beautiful! I’ve won!) She screams her joy! Then kicks off her slippers and pirouettes madly around the living room. “If I don’t die of heart failure now, I never will,” she cries. “I feel just like a merry-go-round, I can’t tell you how happy I am.”

Now she kisses Carlo and murmurs in his ear, “Melanzana Parmigiana” (my little egg-plant), her favorite pet-name for him.

For hours the phone rings—calls from Hollywood, New York, Naples, Paris. And Sophia says “Grazie, grazie,”(Thank you, thank you) over and over again.

The telephone—it’s not ugly, it’s bella—beautiful! She’s been silly, it’s nothing to be frightened of!

Another call—this time a suggestion: her Oscar victory should be suitably celebrated with an appropriate black-tie ceremony. Nothing for her to do but to show up at the affair; the committee would take care of all details—invitations, press coverage—everything. With tears of gratitude, Sophia whispers into the phone, “Grazie.” . . .

Brrrrrr-ing. Miss Loren, this is Pietro Nenni’s secretary. Signor Nenni regrets that because of a previous engagement he is unable to come to the reception. (Nenni, a Left-Wing Socialist leader, is reportedly unhappy Sophia’s sister wed Mussolini’s son.)

Brrrrrrrr-ing. Miss Loren, this is the secretary of Entertainment Minister Alberto Folchi. His Excellency regrets that a bad cold will keep him from attending. . . .

Brrrrrrrr-ing. Miss Loren, this is the secretary of . . . Brrrrrrrr-ing. Miss Loren, this is the secretary of . . . Brrrrrrrr-ing. Miss Loren, this is the secretary of . . .

The official reception is cancelled. Instead, a small party is held at Sophia’s apartment. There, she says pensively, “It’s not that I expected a state reception type of ceremony. After all, I am a simple girl. But still, I had hoped to be honored—not so much as an actress—as an Italian receiving such a high international prize. . . .”

Brrrrrrrr-ing. In June comes Carlo’s upsetting call from New York.

All summer long Sophia waits in dread for that one phone call which will definitely set the date when she and her husband must stand trial. All summer long she wrestles with the problem of what they should do: Become citizens of another country? Switzerland is out; the Swiss require twelve years of continuous residence before granting citizenship. The United States? The U.S. might grant them immigrants’ visas if they could get around the moral turpitude clause. Rio? Everybody in trouble seems to be skipping to Rio. But that is for criminals. She and Carlo are not criminals. Appeal to the highest church tribunal, the Sacred Rota? Little chance of a favorable decision there.

Shall they go to Rome and face the music? But can she ask Carlo, more than twice her age, to risk five years of his life? Besides, they both want children so desperately, and in five years it might be too late. Maria is pregnant already, but for Carlo and herself time may be running out.

Every time the phone rings during the long hot summer it seems to bring news that makes her problem even more confusing, her future even more threatening.

But sometimes, while on the phone, Sophia talks back softly, firmly, as if to ward off scandal and persecution by words of faith and of love. “I have been in love only once,” she told me. “Everything that I am I owe to Carlo. For me, he is the only man in the world. We are always on a honeymoon. We are happy everywhere. I don’t care what they do to me. All I want to be is to be recognized as Mrs. Carlo Ponti. . . . I give up. I’m married, I’m not married. I’m this, I’m that. Basta. I feel married, and lots of married people don’t.”

Sometime in early fall a fateful call will tell her when she and Carlo are scheduled to go on trial in Rome.

And whatever she decides to do at that time—go to Rome and fight, or flee temporarily so she can fight another day—this woman, who has survived being called “little stick,” “bastard,” “bigamist” and “adulteress,” will survive this ordeal, too.

—BY CAL YORK

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1962

zoritoler imol

2 Ağustos 2023I gotta favorite this site it seems handy handy