Fire!

Seven people—and they couldn’t find each other. . . . A whole family—separated by walls of fire, sheets of flame! . . . Five kids and their parents—scattered. Homeless. . . . The man—Burt Lancaster—frantic, smelled the smoke half-way home, saw the black clouds piled high in a clear sky. His house was in the worst of it, he knew that. Linda Flora—the whole street—was on fire. He jammed down the car’s accelerator. . . . Now he could see the flames licking fifty feet high—a hundred—a hundred and fifty! He could hear how they spat and crackled—feel the high hot wind that fire breeds and then fattens on. . . . He made it to the Bel-Air gate, and there the police wouldn’t let him pass. Nobody allowed in. Only fire-fighters. . . . “My family,” he gasped, but they had the same answer for everyone. “They’re evacuating the residents now, sir.” He knew it didn’t matter that he was Burt Lancaster. He could be John F. Kennedy and still not go through. But if only he knew where they’d taken the youngsters from Bellagie school. He had two in the school—the two youngest—and it was practically on top of Linda Flora Drive. The police didn’t know where the pupils had been taken. “But Mr. Lancaster, they’ll be safe,” they tried to tell him. “Later on everybody’ll find everybody.”

Later! How could a man wait helpless without knowing for sure his family was safe? They’d all scattered this morning—his wife to a League of Women Voters meeting, the five kids to their various schools. But he’d like to make sure. And what about the help? And this house that he’d put more than four hundred thousand dollars into, through the years?

He had to get his family together! He had to get to a phone! He turned the car around.

This is how it was for Burt Lancaster. And this is how it was for five hundred men. In every studio, every office, every TV station, work was flung aside as they ran for car and home. In how many blazing streets were women and small children trapped without a car to escape in? If the over-burdened fire-fighters couldn’t get to them quickly enough. . . .

At any time in Los Angeles, phone booths are scarce. Now, wherever Burt Lancaster drove, long lines of frantic men were ahead of him. He went mile after mile till he found an empty phone booth.

The line to his house was still busy, as it had been when he’d heard the news and rushed out of the cutting room at Columbia Studios. He tried the League of Women Voters. “Oh Mr. Lancaster,” the voice said, “Mrs. Lancaster is on her way home.”

The fire, which started about eight that morning when a bulldozer hit a rock and showered the dry brush with sparks, was no longer a fire. It was a flock of evil geniuses larking through the drought-dried hills (there’d been no appreciable rain since January, 1961) of Hollywood . . . leaping in great five and ten mile leaps! The devils set not one little blaze here and another there—but four holocausts that joined up to make California’s last great disaster, the San Francisco fire of 1905, look like a kid’s bonfire.

Robert Stack, walking in on the set of “The Untouchables,” heard the news and froze for one horror-stricken moment. His ammunition! He knew what could happen to his beloved Rosemary and their little children and their home if the fire got to his collection of guns and the live ammunition he had always stored there.

Another huntsman, Robert Taylor, knew the same instant shock. At his home, with Ursula and the children, there were not only his guns and ammunition—there were horses that could stampede everybody.

Richard Boone, whose ranch was near Taylor’s, left work on “Have Gun Will Travel” so fast they didn’t know till later that he’d gone. That particular morning his wife had been feeling ill enough to have called a doctor. Because of this, young Peter Boone hadn’t gone to school. And Dick Boone loves his wife and son better than life itself.

To understand the panic all these stars felt you must realize that much of the charm of Bel-Air, and its neighboring location. Mandeville Canyon, is their very wildness. They are in the heart of a big city, yet kept so wild that it is nothing unusual for deer to look in a picture window, or an occasional fox go springing over a lawn. But in a spot where there has been almost no rain the whole long year, too many trees become boxes of matches, too many flower-edged roads become inflamed. And, as many of the men were to discover while frantically driving toward home, too many cars can vapor-lock in the fiercely generated heat.

It happened to James Garner. He had hurled back from the set of “Boys Night Out” at M-G-M and was trying to get to his house, which is about a mile away from the Lancasters’. He had actually been stopped by one traffic cop and given a ticket for speeding! So he was coming into Bel-Air from a back road, to make speed and to sneak by the fire cops.

Suddenly he found himself on a road where the flames were nearly on top of him. The heat was intolerable. His car stopped dead.

Desperately, he tried to start it. The motor wouldn’t turn over. The thought flashed through his mind: He might never get home to save Lois and their children. He might never get home. Period. He might be cremated right here in his car.

There was only one thing to do—and it had to be done immediately. The car was not important, his wife and his family were. Jim jumped out of the car and left it to burn—then, half-blinded by the smoke, began to run home.

Meanwhile, back at the studios, work stopped on all the sound stages—there was something more important to be done. Because movie sets have always been potential fire hazards, each studio maintains its own, very efficient fire department. Studios quickly checked their employee lists as the black smoke clouds piled up, up, up. At Warners, they noted that Connie Stevens and the Jack Kellys lived in the stricken area. Kelly’s home is some thirty miles from Connie’s, but the fire had already covered a forty-mile area.

Since Connie’s home was in more immediate danger. Warners despatched their men there first. Just as they arrived, however, the wind veered. Connie’s house was safe. Overcome with emotion, the young star fell on her knees and thanked God. Very close by, she saw the shifted flames eating up LaVerne Andrews’ home. This was the “key” home of the famed Andrews Sisters; this was the home in which they stored all their mementoes; this was the home in which they had their family reunions. The firemen could not save it. It burned as if made of paper. Everything in it was lost.

The Warners fire-fighters sped quickly through the hills to the Kellys. Jack had been warned to be ready to evacuate, but moments before the firemen arrived, the capricious wind began blowing the flames away from his home.

Firemen from Fred MacMurray’s TV studio had rushed to Bel-Air to save his house. June Haver MacMurray had been out shopping and when she could drive no further, she had to do what Jim Garner did, she had to go home on foot. She took their twin daughters Katie and Laurie, five, to safety. Fred stayed behind to help douse the flames that had reached his house. He thought for sure they’d lose everything, but luckily only the roof burned.

Less than a quarter of a mile away, studio firemen were helping Red Skelton save his $500.000 home. But up on Bundy Drive, Joe E. Brown was not so fortunate. His home, and everything in it was lost. Zsa Zsa Gabor lost her house, too.

The day grew hotter. The fire-created wind blew wildly at close to one hundred miles an hour. The sun was blacked out by the smoke; there was no telling the hour without a glance at a clock. By mid-afternoon 2,500 people, using every piece of fire-fighting equipment in Los Angeles and every other city for fifty miles around, were battling the blaze. But in some places, as in the area where Burt Lancaster lived, the fire trucks could do no good—they did not have enough water pressure. Luckily, the studio fire-fighters carried their own water tanks. That was why they seemed to have better luck in saving homes.

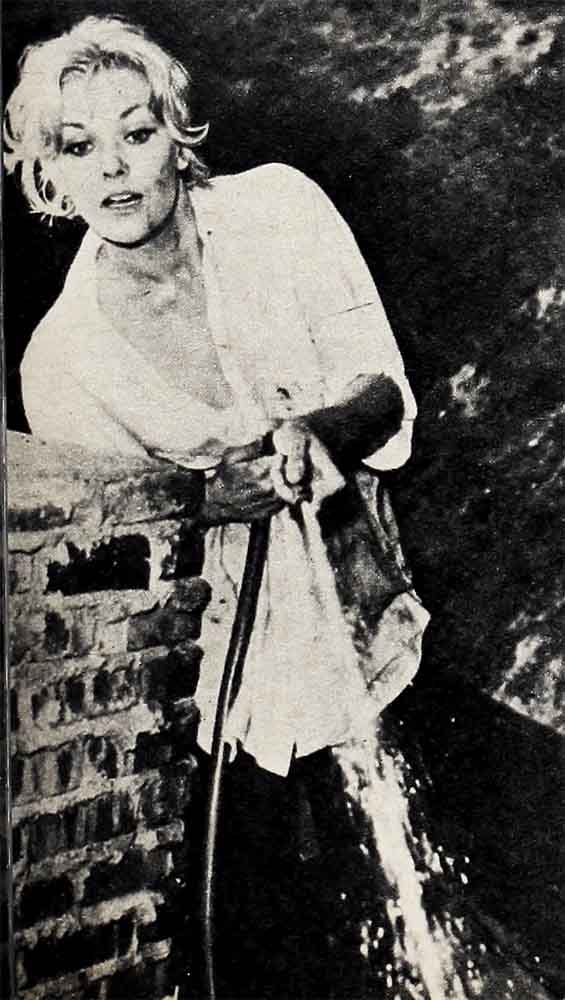

Robert Stack, speeding home, saw the winds miraculously shift as they were about to envelope his home. But in changing course, he saw the flame lap around the little honeymoon house of Barry Coe. Bob glanced up at the sky for a moment, and when he looked again at the Coe home, he saw nothing but the glowing foundation. Kim Novak’s home was very near the Coes’. The houses on either side of hers flamed up. As she rushed back from M-G-M, she detoured long enough to enlist Dick Quine’s help. She won’t say whether or not she loves him, but certainly, at this time of crisis, she proved she needed him. Together, they climbed to the flat roof of her home. They did have enough water pressure—thank goodness. Side by side, as the hours ticked by, they kept hosing down the roof of Kim’s home. They even managed to check the flames that started on two neighboring homes until the wind—that evil, destructive wind—shifted and they were safe . . . safe!

All the women, actually, were wonderfully brave. Ida Lupino, high on the peaked roof of her home, never wavered as the flames licked near her. She and husband Howard Duff fought frantically to keep the roof wet, and to keep the blaze from the brush in their backyard. Like other Hollywood couples, they discovered that as bad as the situation was, they still had each other. With this knowledge, they could fight unafraid.

Jim Garner had the same reassurance when, panting with fatigue, he finally reached his home as his wife, Lois, was backing her car out of the garage. Beside her were their two daughters and a small fire extinguisher. In the trunk, he was to learn, were carefully packed overnight bags. He stopped long enough to kiss Lois and tell her to move over so he could drive. Then, instead of climbing in the car, he dashed into the house. The house wasn’t on fire, but Gardner didn’t even look to see if it was.

Today, Jim can’t tell why, for the life of him, he dashed into the house as he did to save the two objects he did. The first was his wedding ring. He hadn’t worn it to work that day because he plays a bachelor in “Boys Night Out.” The other thing he saved was his passport which, of course, could easily have been replaced. Grabbing them, he rushed back out to the car, drove Lois and the children to a hotel, then went straight back to the fire area. He was going to try to save his home—and he did. He also helped his neighbor, a lonely widow, save her home. He fought the fire all night long and the hot smoke came so close to him, his eyeballs were scorched.

Jim wasn’t the only person who saved objects that had a special significance. When Richard Boone reached his house, he found his tiny wife, Claire, dressed—in all that heat—in her mink coat. In her left hand was an overnight bag, entirely filled with the wonderful jewels Dick has given her. Her right hand firmly held Peter Boone, age ten. Peter was clutching his most beloved object—the guitar Duane Eddy had given him.

As Boone led them to the car, his wife fixed a stern eye on him. “Don’t you dare try to save that Lincoln barber chair,” she said. “I know it’s your most cherished possession, but you can’t get that chair and us in the car.”

They had to go back!

Boone did exactly what Jim Garner did. He took his family to safety, then came back to try to protect his home. This was a compulsion all the men had—they had to go back, they had to, even though none of them knew when the dangerous wind would shift and shower live sparks over them—and their homes.

Bob Taylor went through the fire area at ninety miles an hour, taking his wife Ursula and their children to a hotel. Then he returned alone to his ranch to take out his horses and dogs. The very obedient dogs got into his station wagon without too much difficulty, and he drove them to a temporary animal shelter in a nearby public school yard. The horses were a problem—frantic with fear. Bob could get them to move only by tying a scarf over their eyes and riding them out. one at a time. He had to spur them fiercely so they would run to escape the pain of another spur. He took the horses to Van Heflin’s home—about a quarter of a mile away. There was no fire there—yet! No one knew, however, with the wind the way it was, where the fire would go next. Friends who had offered their homes to refugees, soon found that fire was upon them and they, too, had to evacuate. One of the highest streets of Bel-Air, Chalon Road, burned completely. Dana Wynter and Greg Bautzer, living just below, called friends on Chalon and offered them a place to stay, but in one hour the flames were so tremendous the Bautzers, too, were ordered to evacuate. Of the more than forty homes that burned on Chalon Road area, not one cost less than $100.000.

As the afternoon wore on, the fire grew fiercer, more desperately out of control. Nevertheless, the Los Angeles authorities maintained a fantastic net of communication. In the stricken section, police on foot carried walkie-talkies. In areas that were still safe though threatened, the police patrolled in radio cars. In the air, about the one-hundred-fifty-foot flames, planes dropped four-hundred tons of “water bombs” and reported changes in the fire’s direction. Where TV sets and radios were still operating, exact information was given as to where school children had been evacuated, and where and how parents could claim them.

Burt Lancaster heard the instructions on his car radio as he fiercely circled away from the police. He was determined to get into Bel-Air, though the radio repeatedly warned that his entire Street, his own home and everything in it was gone. (Luckily. Burt’s $250.000 art collection was on loan to a museum.) The house. However, was the smallest of his concerns. What of his wife . . . ?

He saw a gas station along the road. The flames were directly across from it. He realized the danger of explosion—but he realized something else—there was probably a phone in the gas station office. He decided to find it. The office door was open, the station was deserted. He dropped a dime into the phone, wondering whom he should call. He found himself dialing his office.

“Oh, Mr. Lancaster,” a secretary gasped. “Mrs. Lancaster has called. She has the three little girls with her. She wants you to collect the boys at their schools. Philip (the Lancasters’ houseboy) called. He got himself and all the servants out safely. Mrs. Lancaster has engaged a cottage at the Miramar Hotel for the whole family, tonight. She said she knew you’d want the whole family to be together—not even separated by hotel rooms. Is that all right . . . ?”

At that exact instant, a tower of flame came blazing over the road toward the gas station, toward Burt. He dropped the receiver and watched, horrified, as the flames swept nearer. He thought at least his wife and children were safe—even if he was a goner. Then, something happened. A sudden gust of wind, a miracle, call it what you will, but the flames suddenly started to go up, up, up and over the station. They came back down to earth yards away—a direct hit on a grocery store. It was demolished in seconds.

Shaking, Burt climbed back into his car and sped to Emerson High for his son Bill; then to University High for his older son Jim. Together they drove back into the fire area to see if they could help anyone. Burt knew his own home was gone. He knew that his wife might well be angry for his delay in getting their boys to her . . . but he couldn’t help it . . . he had to help others.

The three Lancasters pitched in to fight the demon fire. Working with wet blankets (one home owner had thought to fill every bathtub in his home with water), they beat out the flames in four homes. With one exception. Burt didn’t know the names of the people he helped. They, of course, knew him. As they worked feverishly, no one stopped long enough to notice that the barely visible sun was setting. No one knew that the word was being filtered down that while the fire continued in other areas, the Bel-Air and Mandeville Canyon fire was almost under control.

By late evening. the whole fire was over. The toll was incredible: four hundred and fifty-six homes were lost. The damage amounted to something like twenty-six million dollars. But. Luckily, oh, so luckily, not one single person had been killed. Unfortunately, a few, very few, animals didn’t get out alive, but every man, woman and child in the stricken area had reached safety.

There were, of course, some typical Hollywood happenings. For instance, the Red Cross had set up disaster stations, with cots and food. But not one Hollywood person turned up there. It just isn’t that kind of community. Instead, the mink clad refugees piled into the posh Beverly Hills and Beverly Hilton Hotels. Quipped one wag, “They were the wealthiest refugees since the Russian Revolution.”

Publicity men were quick to capitalize on the fire. Clients, whose homes were not in any immediate danger, were urged to pose, hosing down their homes. When one producer saw a picture of his star in the morning paper, he called his publicity man and bellowed: “What good does this picture in the paper do, it doesn’t even mention my new picture!” Dick Boone, in true Paladin style, had cards printed up: “Have hose, will squirt.”

But that’s Hollywood—and no Hollywood story, whether it be one of a holocaust or a romance, would be complete without those touches.

When the smoke and flames had vanished, how did the victims feel about rebuilding? Burt Lancaster was adamant: “We’ll rebuild. Stone for stone we will rebuild. That’s what the kids want.” Joe E. Brown was less sure. He felt that he probably would rebuild, but maybe not right away. He thought he and his wife might get a trailer and live on their grounds—“That way, if we do decide to rebuild, we can watch it step by step.” Zsa Zsa Gabor, who flew out to Hollywood from New York the day after the fire, sifted through the ashes in hope of recovering some of her jewels. This was the third time she’d been burned out of house and home. Said the glamorous lady, “I’ll never buy another house as long as I live, at least not in Bel-Air.”

And she may have a point. A few days after the fire, a new threat came to that area. It came in the form of a once prayed-for rain. But now the rain was not wanted. The canyon walls, once thickly covered with brush that soaked up excess moisture, were now seared hare. The result: landslides! Steve Forrest, whose home had been saved from the fire, was one of many who had to dam up the sliding mud to protect his house.

Can anything more happen to this once lovely, highly-desirable section of Hollywood? We pray not!

—RUTH WATERBURY

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1962