“Mama, I Can’t Come Home . . .”—James Darren

PART II

Crowded South Tenth Street, Philadelphia, had seen plenty of commotion in its time. But never anything like this! What was up?

James Darren—better known in the old neighborhood as Jimmy Ercolani—was coming home. And this was certainly a cause for celebration. After all, Jimmy and his wife Gloria had been home only once before in the two years since they’d gone to Hollywood—for something like seven hours, between public appearances in Washington and New York—and the fact they were coming in now meant they’d be bringing another Jimmy with them, their year-old-son, to show off to his grandparents and all the other relatives and friends of the family.

Jimmy’s kid brother Johnny and Johnny’s wife had already arrived early that Saturday morning at the tiny row house where his folks and grandparents lived. As had Jimmy’s Aunt Sara, with her daughter, Lorraine.

And a truck from the bakery. And a truck from the big Italian grocery store down the street.

Now, a little after ten o’clock, another car was pulling up—this time with Jimmy’s Uncle Mannie, his wife Cora and their daughter Vicky.

And then, right behind it, came another car—with Uncle Dominick and Aunt Betty.

A third truck another car was pulling up—this time with Jimmy’s Uncle Mannie, his wife Cora and their daughter Vicky.

And then, right behind it, came another car—with Uncle Dominick and Aunt Betty.

A third truck followed, a very fancy red truck with a giant stork painted on its side and with a crib and highchair tied to its back, both of which were removed by the driver and his assistant and carried into the house.

And then came still another car—this one carrying Uncle Stanley, his wife Mary, and their infant son, Stanley, Jr.

“By eleven o’clock,” said an old man sitting with a crony on a stoop across the way, “I bet you there are thirty people in there.”

“Fifty,” his friend said, contradicting him. “Maybe even fifty-five!”

Actually, the second old man was closer to the truth.

But at the moment, inside the bustling house, Jimmy’s folks and grandparents weren’t concerned about whether there’d be fifty-five or a hundred-and-fifty-five people visiting that day. All that was important to them was that Jimmy, Gloria and the baby had left Hollywood on the midnight flight, that they were going to be home at about noon—and that they had to be ready for them.

“Now everybody relax nice in the living room while Mama and I start preparing the lunch,” Mrs. Ercolani was saying to the gang of new-arrivals when the phone rang.

“Jimmy?” she cried into the receiver, surprised, a moment later. “But Jimmy, you’re supposed to be on the airplane, I thought. What are you doing calling from California?”

She listened as Jimmy explained. Just before they were supposed to leave last night, he said, he’d gotten a call from the studio to stand by for a conference the following day, Saturday. It was almost 3 A.M. Philadelphia time when this happened, he said, and that was why he hadn’t phoned then.

“But you will come?” Mrs. Ercolani asked now, “hah, Jimmy?”

Jimmy said “Sure”

She nodded to the others, relieved, and Jimmy said sure he would. The conference was scheduled for a few minutes from now, he said. He had no idea what it was about. But it surely wouldn’t take long, he told her. And then, right after it was over, he, Gloria and the baby would dash out to the airport and make it home just about in time for supper.

“Oh, good,” Mrs. Ercolani said, all smiles again. “A lot of us are here already. And don’t worry about the baby not being comfortable when he gets here. Because we bought a nice crib for him and a highchair and everything.” She sighed. “Oh Jimmy,” she said, unable to hide her excitement, “how we’re looking forward to seeing him after all this time.”

Then she glanced to her side where her mother was standing now, obviously anxious to talk to her grandson. She handed her the phone.

“Hello, my movie star,” the old woman said as she took the receiver and cupped it to her ear. “Listen, come home right away because we make the ravioli for you. Si, the ravioli like you used to like them when you were small, with the ricotta cheese and the spinach in them. And we make the pizza—not the frozen kind you have to eat out there in California, but the real kind with the dough we make ourself. And tomorrow morning, Jimmy, I make you the eggs, nice—sunny-sides up. Remember, Jimmy, how when you were small you said I was the only one who could make the eggs good?” She laughed. “Now hurry up and get on the airplane after your business is finished. And wey, don’t forget to bring my great-grandson with you. Remember, I never seen him and I wait all this year to see him.”

The hours after that went by swiftly. By noon, everybody who had showed up already sat down to lunch—in shifts. And then, starting at about one o’clock, the rest of the crowd began to appear . . . in twos, fours and what-have-yous . . . more relatives and old friends of the family from the neighborhood, pals of Jimmy’s from school, some of Gloria’s girl friends from her old neighborhood . . . practically everybody from that part of Philadelphia, it seemed.

Remembering Jimmy

It was about three o’clock when Mr. Charlie showed up. Mr. Charlie was manager of the Colonial, a movie house around the corner from the Ercolanis, a big jolly man who had known Jimmy since he was a kid.

“That Jimmy of yours,” he laughed, after Mr. and Mrs. Ercolani had greeted him, “I remember having to shoo him out of the movie house practically every Saturday afternoon because he was too noisy. And now here it is, a Saturday afternoon a few years later, and I drop by to say hello to him—a big actor, just back from Hollywood!”

Mr. Charlie looked around the crowded room.

“Where is he, anyway?” he asked.

Mr. Ercolani had just begun to explain what had happened—how Jimmy had been delayed, but how he was probably on the plane this very minute, headed East—when the phone rang again.

Mr. Ercolani excused himself and picked it up.

Then, a few minutes later, after talking over the loud festive chattering, he hung up and called out for everybody to please be quiet.

“That was Jimmy again,” he said, softly, signaling his wife over and taking her hand in his. He tried to smile, “Jimmy told me he has some good news. He said that he just talked to a big vice-president at the studio where he works and the vice-president told him he’s got an important part in a big new picture. It’s called Gunman’s Walk, I think Jimmy said.” He cleared his throat. “Only thing,” he went on, “is that the picture starts shooting next week and so Jimmy can’t come home.”

“He can’t?” Mrs. Ercolani asked.

“No,” her husband said. “But . . . but he told me not to send the crib back to the store because he and Gloria and the baby would definitely be here when the picture’s finished, in a few months.”

“In a few months?” Mrs. Ercolani asked.

Her husband nodded.

Keep the crib

“Of course we don’t send the crib back,” Mrs. Ercolani said suddenly, looking around the room and trying to smile, too. “And so what they don’t come home today like we expected they would? After all, a big part in a picture is important. And you don’t get them every day. Do you?”

But she didn’t wait for an answer from the silent crowd. Instead she turned and rushed out of the living room, to her own room, where she could have a good long cry.

At that moment, in Hollywood, Gloria was giving the baby his lunch.

“Jimmy,” she called out to her husband as she wiped the last traces of strained prunes from young Jimmy’s face, “are you ready, honey?”

“Yeah. Whenever you are,” she heard her husband call back.

She shook her head. She was disappointed about the trip being called off suddenly, sure. But she’d never seen her husband act so sad about anything in his life. In those last few minutes she’d tried to lighten things a bit, reminding him how important this new role would be to his career, how lucky he was to land a part in a Grade-A western. But Jimmy wasn’t buying any career-talk now, not for all the tea in China or all the Grade-A westerns in Hollywood. “They’d counted on seeing the baby, finally, so much,” he’d said instead, over and over. “It’s gonna break their hearts now that we can’t make it.”

The tonic car

Gloria had waited just a little while, and then she’d suggested they go for a ride somewhere. She knew from experience that Jimmy’s car was his best medicine, that an afternoon behind the wheel would help take his mind off his big disappointment.

As it turned out, this was one time Gloria couldn’t have been more wrong. Because Jimmy wasn’t a sulker by nature—but he certainly did a lot of sulking for the rest of that afternoon.

Gloria noticed it as they drove to the beach first—how her husband didn’t say a word all during the drive. Then on the beach, as he sat making little sand castles with the baby—how he still didn’t say anything. And then, all through the snack they stopped for at a drive-in, how he acted just the same, quiet, unsmiling, thinking of how things would have been in Philadelphia at that moment if they’d been able to make the trip, thinking of the happy faces, the big long hugs, the laughter, the excitement over the baby.

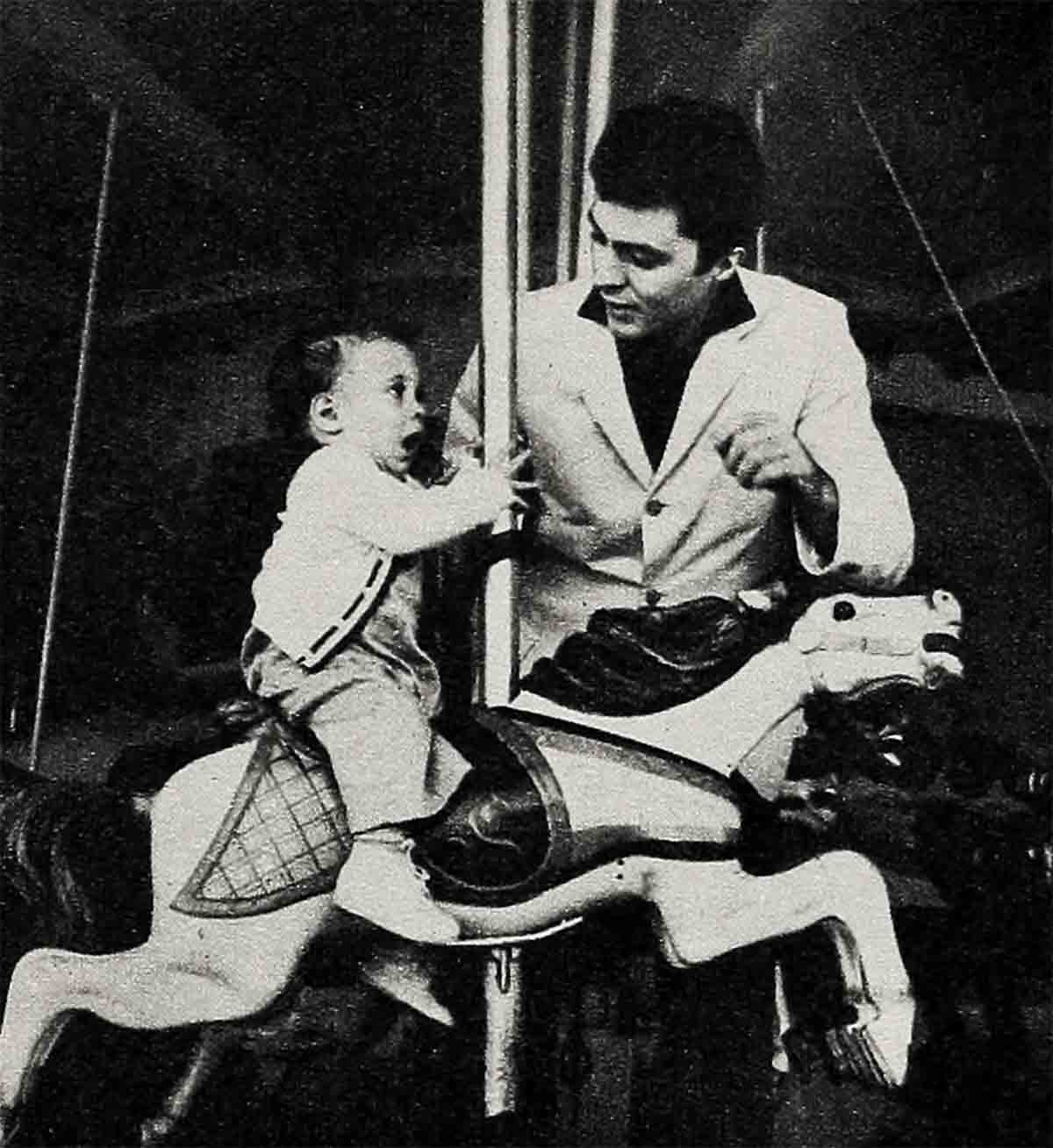

Even when they got to Kiddieland—an amusement park for children and Jimmy, Jr.’s favorite spot in all California—Jim, Sr. remained glum.

He went through all the usual motions, all right. He took the baby on most of the rides. He bought him a frozen custard cup. He picked him up when he was tired. He put him down when he wanted to start running around again.

But he did it all slowly, mechanically, with about as much spirit as a heart-sick puppy—and it wasn’t until just before they were ready to leave when something happened that changed everything for Jimmy.

It started with the baby.

Jimmy, thinking his son had really had it by this time, had picked him up for what he thought was the last time that afternoon and begun to head back to the car, when suddenly the baby began to squirm.

“What is it, Buddy?” Jimmy asked.

“Wan’ go,” the baby said. “Wan’ go.”

“You wanna go where?” Jimmy asked.

He watched as the baby pointed to the one ride he hadn’t been on that day—the airplanes.

“Well, Buddy,” Jimmy said, “that’s very funny, because you almost went on an airplane today. You and your Mommy and me, we all almost—”

“Plane,” the baby nodded, interrupting him. “Me on plane, Da-Da.”

Jimmy shook his head. “You almost on plane—” he started to say again, when all of a sudden he stopped walking and stood there now, thinking about something and beginning to smile.

“Wan’ go,” the baby kept saying, over and over, as Jimmy continued standing there, as the smile on his face grew broader and broader, until Gloria—who’d been walking alongside them, not paying any particular attention to what was going on just then—turned to Jimmy and asked, “What are you grinning about?”

“Glo, I just got an idea,” Jimmy said.

“What’s that?” Gloria asked.

“Glo,” Jim explained, his voice triumphant, “the baby—he just gave me a great idea!”

And this is it

Things were quiet at the Ercolani house in Philadelphia the next morning. Jim’s folks and grandparents had gone to early Mass at the church down the street and they were back home by ten o’clock. Sunday was normally a pretty lively day at the house—with maybe Johnny and his wife invited over to dinner along with some other relatives and some friends, too. But this particular Sunday had started quiet and, as far as the Ercolanis were concerned, it would have been silly to try to liven it up. The wonderful fun they’d expected to have the night before—and now, today—just wasn’t going to be. That they knew, and there was no sense in kidding themselves that anything could make up for their disappointment.

Even when, shortly after one o’clock, Mrs. Ercolani’s brother Dominick and his wife Betty showed up unexpectedly—a little out of breath and smiling to beat the band, for some strange reason—the Erecolanis and Jimmy’s’ grandparents couldn’t rouse much enthusiasm.

“Nice to see you,” Mr. Ercolani said, shaking his brother-in-law’s hand.

“Good to see you, Ray,” Dom said. “Any phone calls yet?”

“What do you mean any phone calls?” Mr. Ercolani asked.

Dom looked down at his watch. “Oh, I just thought maybe you got a phone call or something this morning,” he said, turning to Betty and winking.

The others looked at each other, confused.

“Dominick,” Mrs. Ercolani asked her brother, “you sure you’re feeling all right today?”

“Sure,” Dom said, looking down at the watch again, “I’m feeling fine.”

Then he looked over at the phone and pointed to it. And sure enough, suddenly, it rang.

“What’s going on here?” Mrs. Ercolani asked, more confused than ever now, as she went to pick it up.

“Hollywood?” she was asking into the ‘receiver a moment later. She nodded and looked at her husband. “It must be Jimmy again, to say hello,” she said.

“Hello, Jimmy?” she called into the receiver, after another moment.

“Hello, Mom,” she heard Jimmy’s voice ‘greet her, “how are you?”

“Fine, Jimmy, fine,” she said. “And you and Gloria and the baby?”

“Great, Mom,” Jimmy said. “But boy, I sure feel bad about what happened yesterday, us not being able to show up.”

The vinto

“Oh, well—” Mrs. Ercolani started to say.

“I know how much you all wanted to see the baby, huh, Mom?” Jimmy interrupted her.

“Well, sure.”

“You’d really like to see that grandson of yours, wouldn’t you, Mom?”

“Of course, Jimmy, but—”

“Mom,” Jimmy said, suddenly, “do me a favor. Go open the door.”

“What door?” his mother asked.

“The front door,” Jimmy said. “Go ahead, go open it.”

Mrs. Ercolani sighed. First her brother acting cuckoo. And now her son. “Jimmy, you haven’t started drinking since you’ve been out there in California, have you?” she asked, worried.

“Mom,” Jimmy said, chuckling, “please . . . Just go open the front door.”

She opened it.

“Hello,” a pretty young woman said to her.

“Hello,” Mrs. Ercolani said—not recognizing the young woman at first, nor the baby she was holding.

Then, suddenly, she did recognize them. And she shouted, “It’s Gloria! And Little Jimmy!”

A long long-distance

As Big Jimmy himself describes what happened after that:

“I must have been on the phone for three or four minutes, just hanging on; listening to all the shouting and yelling and crying when the family saw Gloria and the baby standing there. Mom was too excited to come back to the phone to talk to me. Honest, I think she forgot about me altogether those next few minutes. But when my Pop got on the phone I explained to him what had happened, how I’d decided the night before to let Gloria and the baby come even if I couldn’t make it, how I’d called Uncle Dom and Aunt Betty and told them about the plot, how they’d met Gloria at the airport and then how we had it all arranged that I’d phone at 1:15 on the dot and have Gloria and the baby waiting behind the door.

“It all worked out perfectly. And even though my Mom never came back to the phone, I remember my grandmother did at one point.

“ ‘Hey, you, she said, after raving for a few minutes about Jiminootz, her little great-grandson, ‘why you no come home?’

“I explained again about the picture I had to start working on.

“ ‘But we got some of the ravioli left over from yesterday, still nice and fresh,’ she told me.

“ ‘I tell you what, Nonna’ I said, ‘in a little while, just when you’re all sitting down to eat, I’ll go to a restaurant around here and I’ll order a meal just like yours and then I can make believe we’re all together. All right?’

Jimmy was in the restaurant about an hour later, a little Italian eating place on Sunset Boulevard, not far from his and Gloria’s apartment.

Sitting alone, he ordered the meal his grandmother had said she and his mom had prepared, item for item.

Then, closing his eyes, he lifted his wine glass and began to whisper a toast.

“Did you say something?” a waiter who was passing by asked.

“Uh, no,” Jimmy said.

“Oh, just practicing for a movie?”

“Yeah, that’s right,” Jimmy said, smiling, “just practicing.”

Still smiling, he looked around the table—at the places where he imagined his dad was sitting, and Gloria, and Grandma and Grandpa, and Mom, proudly holding the baby in her lap.

Then, making sure the waiter was gone, he lifted his wine glass again, took a sip and whispered buon appetito—hearty appetite—to a very happy group of people, three thousand very far miles away.

THE END!

—BY ED DEBLASIO

Watch for Jimmy in Columbia’s GUNMAN’S WALK.

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE JUNE 1958