“Did You Ever Just Have To Tell A Lie?”

Sandra huddled deeper into the big hotel armchair, as if, by making herself as small as she could, she could escape. But she couldn’t get the picture out of her head. She could see herself standing in the middle of the big stage in her old Public School #3 in Bayonne, New Jersey, and she could hear a titter and a snicker growing into a loud roar of people laughing at her. She opened her mouth but no words came out. all the people who’d known her as Alexandra Douvan had come to see her now as Sandra Dee. But she couldn’t think of anything to say. She was just standing there, in front of all the people who didn’t like her anymore. The laughter grew louder and louder.

She put her hands to her ears to stop the roar. They must like me a little, she tried to tell herself, or they wouldn’t he giving her a Sandra Dee Day.

She could hear the steam hissing in the hotel radiator, but she shivered. She felt cold. They used to like me, she told herself. She closed her eyes and tried to remember how things once were.

The last time she’d been at the grammar school auditorium she was eight years old and it was St. Patrick’s day. There were green paper streamers and all sorts of decorations hanging all over the assembly and the whole school was out there in the audience, waiting to see the play they were putting on. It was the last play she’d be in at this school, because they were moving to New York. She wished they weren’t moving. She didn’t want to leave her friends. And even the teachers here were nice to her. Some of them had had her mother in their classes and one teacher had even told her that she’d known her grandmother as a girl. Of course, it had been a high school then, but even so, it was hard to imagine that long ago.

She’d peeped around to look at the stage. It was so big. It was bigger, she thought, than the one at Radio City Music Hall, where her mother had taken her once. And then the teacher had come over to her. “Ready?” she whispered. Sandra nodded, her blond curls bobbing as she shook her head up and down. The school band started to play her introduction and the teacher gave her a little pat, to start her on her way. And then she was doing her dance step, making her way right to the middle of that big stage. She stole a look at the audience. There were so many kids out there. She took a deep breath and started to sing, “Peggy O’Neill . . .” All the kids had clapped for her and she’d smiled out at them and held out the full skirt of her dress in a curtsy.

“Ooh, Sandy, you were wonderful,” a little girl had whispered to her backstage. “Weren’t you scared?”

“No,” she’d said, “I wasn’t scared.”

But later, when she thought about it, and about leaving all her friends, and, when nobody could see her, she cried.

The day they moved away, her mother had hugged and kissed all her friends goodbye. Her mother was like that; she always let people see how much she loved them. “I’m not like that,” she thought. “I’m not affectionate at all.” Sometimes, because she didn’t show how she felt, people thought she was a snob. But that wasn’t true. She really liked people, only it was hard to show it.

Then her mother’s voice, calling from the other room, brought her sharply back to the awful present.

“Sandy,” her mother called. “It’s getting late.” Her mother poked her head in the doorway and gave her a long look. “Nervous?” she asked. “You’ve hardly said a word all morning.”

Sandra shook her head. “No,” she lied. “I’m not nervous. I’ll just pretend that Bayonne is like any other town.” She could feel the blood rushing to her face at what she’d just said to her mother and she turned away so her mother wouldn’t see. It was just a little lie, a fib really, she tried to tell herself, but she’d told it to her mother. That made it seem like a whopper. She and her mother were so close and she never lied to her, even about little things.

She didn’t understand why she wanted to hide what she felt, even from her mother, but inside she knew it wasn’t true. Bayonne wasn’t at all like the other places she’d been on her tour for “The Snow Queen.” If the people in your home town don’t like you, she thought, it doesn’t matter how much people in other places say they do. Bayonne was where it really mattered. The day meant so much to her and she wanted to show the people how much she loved them.

If she could only find the right words . . . the right way.

“I thought you might be a little worried about making that speech,” her mother said. “I still wish you had something all prepared.”

“No, I don’t want it to sound rehearsed,” she said. “I want to say what I really feel. It’ll come to me when I get out there.” She wasn’t really sure about that. Making a speech was scary. Maybe she’d get out there and open her mouth and nothing would come out. Her mother always teased her about how much she talked and talked. But maybe today she wouldn’t be able to think of anything to say.

“There’s really nothing to be nervous about,” her mother went on.

“I am not nervous,” she insisted slowly and emphatically, getting up out of the armchair to go into the other room to dress.

But there was a lump in her throat that made it hard to swallow. She was afraid that if she said how she really felt, if she admitted she was nervous, it would be worse. She could feel her mother’s eyes on her. Her mother always said how good Sandra was at hiding her feelings. She could look one way on the outside and feel completely different inside.

If she didn’t have to make that speech, it wouldn’t be so bad. She could really enjoy this day. Even, she thought, glancing out the window, if it was raining. She looked at the pale blue dress and coat she’d hung on the door of the closet the night before. Maybe, with the rain and all, she should wear something else. She looked through the closet, finally pulling out a tweed suit with a fur collar.

Then, when she was finally ready to leave, she gave her hair an extra squirt of spray, hoping that would help it stay in even in the rain.

The first place they stopped, once the car had crossed from New York into New Jersey, was a dress shop in Bayonne. The woman who ran it was an old and dear friend of her family’s.

“Sandra,” she beamed. “Why I remember you . . .” she held out her hand to show how high Sandra had been. Her mother and the woman kissed each other, but Sandra held back. How could you kiss someone you hadn’t seen for ten years?

I remember you, too, she thought, smiling at the woman. Mother had always bought her dresses here and she’d always taken her along. They only had grown-up dresses and so there’d never been anything for Sandra herself. But when her mother disappeared into the fitting room, she’d look through the racks of dresses, standing on tiptoe so she could turn them over, one by one, and plan which ones she’d get when she was big enough.

Once, there’d been a blue dress. “For afternoon weddings,” the woman told her. Sandra had reached out gingerly to touch the delicate silk, holding her breath. There’d been paper spread on the floor where someone else had tried on a long dress and they hadn’t wanted the hem to get soiled. So the woman had let her hold the dress up against herself and she’d turned slowly in front of the big mirror, the skirt sweeping down on the floor, ’way too long for her, as she tried to imagine how she would look in it. She looked through the racks now, while her mother talked to her old friend, but there wasn’t anything there in that same shade of blue she remembered.

Then they got back in the car. “I’m so excited,” her mother said, “aren’t you?” As if to avoid having to answer, she looked out the window. Bayonne hasn’t changed, she thought, it’s still just the same.

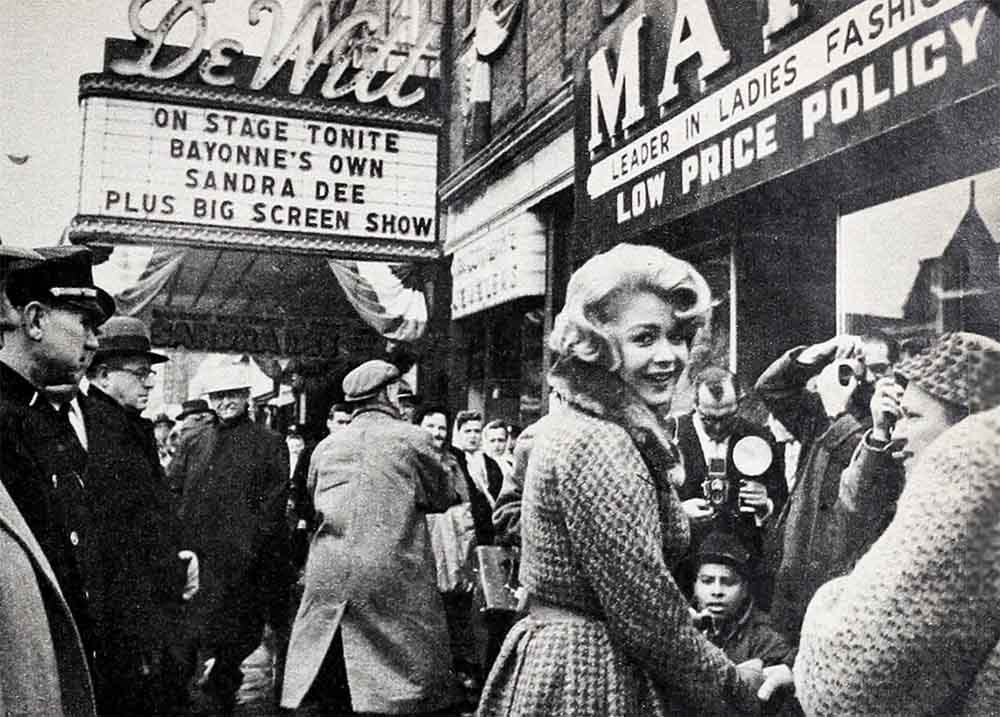

When they got to the school, there was a big crowd waiting outside. She hadn’t thought there’d be that many people. Some of the faces looked familiar and the people were all waving to her as if they knew her. She waved back.

There were crowds of people inside, too. As she made her way to the assembly, they all waved and called out to her, as if they had a personal interest in her, as if they were friends as well as movie fans.

And then she noticed the decorations. She blinked her eyes. It didn’t seem possible and yet . . . It was as if they were the same decorations there’d been that day ten years ago, when, crying, she’d left the school. The crepe paper and streamers were draped about the stage just the same way they’d been then, She could feel the lump in her throat getting bigger and she felt as if she was going to cry. She hoped she wouldn’t. She tried harder to concentrate on the music they were playing on the loudspeaker. It was her record of “Do It While You’re Young,” she discovered in surprise. She was so nervous she hadn’t recognized it. Then the principal. Dr. Phillips, came over to greet her. She’d always been in awe of him when she was a student here; he’d seemed so tali and stern and important. But now he smiled at her, a nice, friendly smile, and he didn’t seem like anyone you’d be afraid of. She smiled mistily back at him.

She noticed a tali young man on the platform. He looks nice, she thought. I bet he’d be a great teacher to have. Then he came over to shake her hand. “Remember me, Sandra? We were in the same class.”

He’s so grown-up, she thought. Have I grown up that much, too?

She remembered him now. They’d gotten in trouble together when they were in the second grade and he’d copied some answers from her in a test. He’d been caught at it and she remembered how guilty she’d felt for days afterward. She felt she’d been in the wrong, too, for being the one who let him copy. But they hadn’t gotten into too much trouble, because they were only in second grade. She wondered now if the answers he’d copied from her had even been the right ones. She couldn’t remember.

They all found seats on the stage and then the principal made a speech. It was hard to concentrate on what he was saying because she was so full of emotion. Then a little girl came out on the stage. Sandra guessed she must be about eight. And she began to sing her song, the one she’d sung in the St. Patrick’s Day play. Only instead of “Peggy O’Neill,” the little girl was singing “Sandra Dee.”

Everybody cheered and clapped. Sandra applauded the little girl, too. She felt a tear drop from the corner of her eye and she let it fall slowly down her cheek, so nobody would notice but then the other tears began and she had to fumble in her purse for a tissue and the tears followed so quickly that suddenly she was crying so hard she couldn’t see.

Someone handed her a handkerchief and she wiped her eyes—embarrassed—and blew her nose hard, but she just couldn’t stop crying. Everything was misty but she could see now that her mother was crying, too, and the man from Universal who’d come along with them that day and had never even been in Bayonne before in his life, was also crying. She could see that her mother was looking at her a little worried and, sniffing, she tried to smile. She guessed her mother was worried because once she started to cry she never could stop.

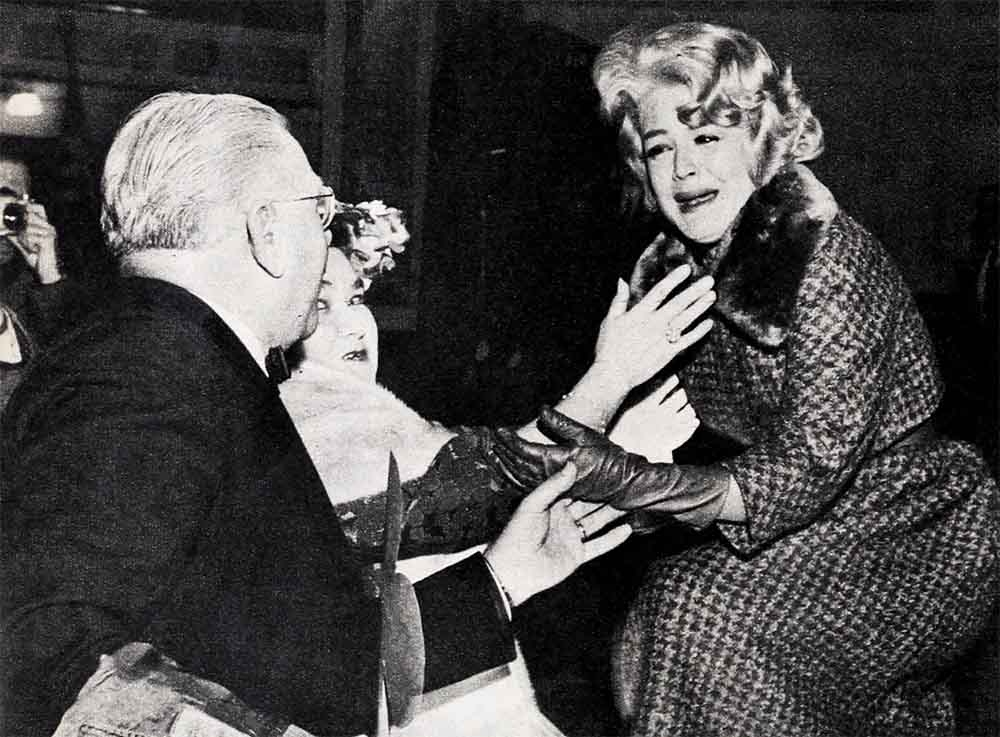

The president of the Board of Education—his son had been in her class and he was up on the platform, too—got up and went to the center of the stage, where they’d brought a wooden speaker’s rostrum. Someone nudged her and she went to stand next to him. He gave her a loving cup and an honorary diploma and made a little speech. She still couldn’t stop crying. Everyone was being so nice to her, but it only made her cry more.

It was her turn now. She was supposed to make her speech. But she just stood there, the loving cup and the rolled up parchment diploma clutched in her arms, the tears streaming down her face, and she couldn’t say anything.

She’d been scared that this would happen and, that morning, she’d thought that if she got up on this stage and couldn’t make her speech, she’d die, she’d want the wooden planks to open up and swallow her. As she stood there, dabbing at the tears that wouldn’t stop, she felt a little funny. It was embarrassing, crying in front of all these people. But nobody laughed at her for it. They were her friends. And for one giddy moment, the thought flashed across her mind. I won’t have to make the speech after all.

Finally, she took a deep breath. She knew she had to say something. She looked out at the faces, at kids who were going to the same classes she used to, at the teachers who’d always been so nice to her, not at all the way people say teachers are. And she managed to blurt out hoarsely, “School’s out!”

They all cheered. I guess, she thought, that was the right thing to say.

The rest of the day passed in a daze. These people were doing so much for her; there were so many of them being so warm and friendly. They’d known her grandmother and her mother and, everywhere they went, people would come up and say, “I remember you, Sandra . . .” She couldn’t remember, afterward, what she said to them. There was the woman who had the hat shop and who used to always scare her a little bit, but who seemed so nice today. The secretary of the dancing school she’d gone to came up to her. “I came across this the other day, Sandy,” she said, and, reaching into a big black handbag pulled out the birth certificate they’d thought was lost. There was Father William Kreschik, whom she’d always called Father Bill and who lived just three doors away from them, near enough to buy her an ice cream cone every day. And Father Michael Chanda who asked her, the way he always did, knowing in advance that she’d answer yes, “Going to church, Sandra?”

They had a luncheon for her at the Kiwanis Club and then she talked with some of the kids from the high school, at a press conference. She wished, “Please don’t treat me like I was different from you.”

Sometimes, other kids would make her feel different by the way they acted toward her. It had happened before, in Hollywood, where a couple of the kids she used to know in Bayonne had also moved. She’d go over to visit with them and they’d just stare at her as if they expected her to do something real crazy, or maybe start to sing and dance right there in the middle of the living room because she was now an actress. It bothered her and, usually, she’d end up in the kitchen with her friend’s mother, who made her feel more at home.

As she drove now to the DeWitt movie theater where she was going to meet Mayor Brody, she remembered how she used to load up on hot dogs from the little stand around the comer, hiding them so the ushers wouldn’t see as she went past them into the movies. She used to be mad about Debbie Reynolds and Janet Leigh and Tony Curtis. She still was. Today, when people told her she was a movie star she didn’t feel it. And when she’d look at herself in a mirror, she’d think, “Why should people treat me as though I were something great? Why me? I’m not any prettier than anybody else. In fact, I hate the way I look. Why do they try to make me different? I don’t feel any different.”

At the DeWitt, they were showing “The Snow Queen,” in which she was the voice of one of the characters. On stage, the mayor handed her the key to the city.

Then everyone was quiet as though they expected her to say something.

She looked out at the audience. They were mostly young people, high school students, she guessed. In one of the front rows, a young girl with a blond ponytail stared up at her. Sandra thought she looked familiar. Were you in my class? she wondered. The girl sat there, an expectant look on her face. But she wasn’t smiling, even a little bit, and Sandra couldn’t tell if she liked her or not.

She had nothing prepared and she stood there silent for a moment, wondering what to say. She remembered how she’d cried at assembly that morning. If you cried in front of people, she thought, then just talking to them shouldn’t be so hard. She decided she’d just say what she felt.

“I’ve been to many towns . . .” she began.

“But this is where I was a little girl. This is where the people are who really count. If I thought you didn’t like me . . .”

All through her speech, she watched the girl’s face. At first, she couldn’t tell what the girl was thinking, but when the speech was over, she saw her smile up at her and she was clapping her hands together hard. They like me, they really like me, she thought. And I didn’t let them down after they’d made all these wonderful arrangements for me and invited me to a special Sandra Dee Day.

Afterward, they drove to where her aunt, Olga Duda, lived. She went into one of the bedrooms and, lying down, she put one arm around a giant teddy bear that belonged to one of her nephews. She pressed her cheek against the soft fur and thought back over the day.

She’d told a whopper that morning, she thought, when she’d said she wasn’t nervous, when she’d pretended Bayonne could be like any place else. But she’d only said it because she was scared. She was worried about her speech and she didn’t know what the people in Bayonne would think of her. She’d been afraid to show them what she really felt.

It had really been an innocent “fib,” and yet all day long the thought of it had nagged at her. She and her mother were usually so honest with each other, that she’d felt bad about trying to hide something from her mother. Mother loves me so much it shows a mile, she thought. Maybe she should have tried to show her mother how much she loved her, too, by confiding in her, by asking for her help.

Maybe, though, her mother hadn’t really believed her. Her mother had stuck right by her all day, as if she really knew the truth and was ready, if only Sandra asked, to help.

Maybe it had been silly to try to hide what she felt. She wasn’t ashamed now that she had cried. There’s nothing wrong in that, she thought. It’s really better when you do show people how much you care.

—MILT JOHNSON

WATCH FOR SANDRA IN U.I.’S “PORTRAIT IN BLACK” AND LISTEN FOR HER VOICE IN “THE SNOW QUEEN” FOR U.I. SHE SINGS FOR DECCA.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JULY 1960

No Comments