Why Jerry Lewis Gives Pieces Of His Life Away?

“Sorry, there’s no story,” Jerry Lewis told me. “I can’t discuss that subject with you at all.” As a writer, I just couldn’t drop a story that easily. I had to try a little harder. So, matter of factly, I asked Jerry if it would be okay if I just hung around for the day to see if I could pick up some information. Jerry said, “Sure, come. I have to do some things for the Muscular Dystrophy campaign.” Surprisingly enough, my assignment was directly connected with that. I’d been told to get Jerry to talk about his ten years as chairman of the Muscular Dystrophy Association. Find out about the kids he’d helped. Ask how he got interested in dystrophy in the first place: For publicity? By request? Had anyone in his family had the dreaded disease? The assignment had seemed a simple one. But when Jerry refused to talk, I knew it was going to be tough. That day, it led me all over New York City. The following week, I chased clues to Hollywood. But the hardest, most forbidding journey of all was the final one: the unchartered journey deep into the famous comedian’s secret heart.

My day with Jerry began on a fabulously furnished bus that had been lent to him by Paul Cohen, president of the Tuck Tape Company. He was seated with Jerry at a table by the bus’ big picture window. Jerry was busy making faces at the people clustered around outside. He’d make a face, grab his camera and take pictures of the crowd watching him. The bus was parked behind the Manhattan Center, an auditorium on 34th Street, where he was scheduled to give a pep talk to muscular dystrophy volunteers. It was the day before their annual citywide drive for funds.

Jerry put his camera aside and pointed out the window. “There’s all the material any comedian needs,” he said. “They don’t know how funny they look to us. and we don’t know how funny we look to them. That’s the basis of comedy.” Clearly he wanted to get off the subject of dystrophy as fast as possible.

“Jerry, would you mind at least telling me why you don’t want to discuss your work with muscular dystrophy?” I asked.

“Because.” he said. “it would sound like l’m blowing my own horn if I told you what I’ve been doing. And as for how I got interested—I don’t want to tell that to anyone. Which reminds me—anyone for tennis?”

“It’s a very nice racket. I’m told.” an aide chimed in.

“Say, what’s that fly doin’ in my soup?” said Jerry.

“Looks like a breast stroke to me,” his aide replied.

I made a notation on a pad I was carrying: “This man doesn’t need a stage. He’s always on, no matter where he may be.”

It was time for Jerry’s speech. He entered the Manhattan Center through the back door.

If I’d hoped to learn something about his dystrophy work from his pep talk. I was disappointed. He answered questions about fund-raising, talked a little about the disease—I already knew it was a usually-fatal degeneration of the muscles, a particular threat to children—and he clowned around a bit. Maybe it was my imagination, but as he walked off the stage after the speech. I thought he shot a triumphant glance in my direction as if to say. “Hah! Didn’t tell you a thing, did I?”

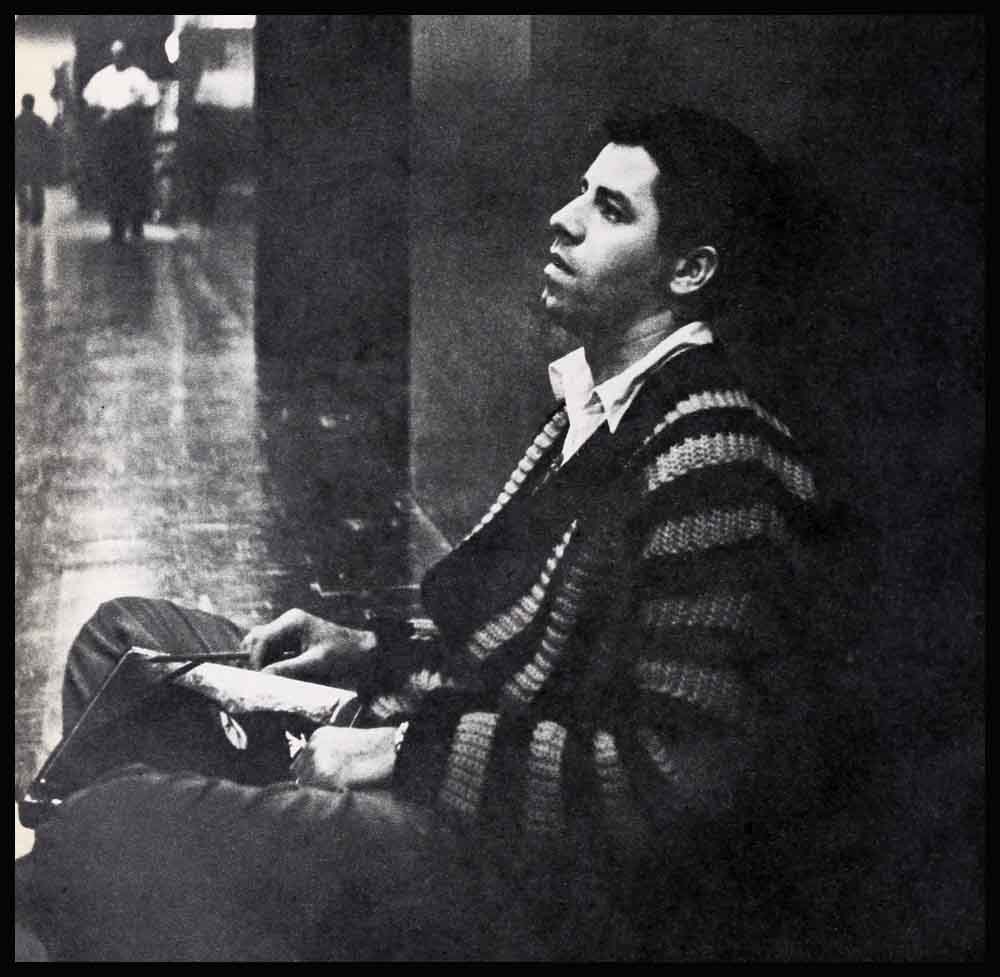

Back in the bus, we headed for our next stop, Manhattan College. As Jerry relaxed at the card table and I lounged on a sofa near him. I made notes on his elaborately stylish clothes: California-weight sport coat of blue, green and black checks with gold buttons. (Later, because I asked about it, he showed me a label inside that said: “Designed Exclusively for Jerry Lewis by Sy Devore.” Sy Devore is an expensive Hollywood tailor patronized by top stars.) Silk blue-grey slacks. Black tie. Yellow button-down shirt. (“By Nat Wise of London.” Jerry told me later.) Tiny rectangular gold wrist watch. Elastic-sided black shoes with a loop at the back. If you didn’t know this man was rich, his clothes would tell you.

“When did you start this tour for muscular dystrophy?” I asked. “I assume that’s public knowledge?”

He smiled. “Yeah, guess I can tell you that. I started last August third, and I have an appointment to eat in June. No, actually we started three days ago and it’s been non-stop. We’ve slept about six hours in three days. But this is nothing unusual. My work schedule in Hollywood is about the same. I’m the only guy who makes two pictures that take eighteen months each in twelve short months.”

He looked out the window and saw a branch of the Bowery Savings Bank. By now we were in upper Manhattan. “Hey, what’s the Bowery Savings Bank doing in Harlem?” he asked.

“It’s for people who save Boweries,” his aide replied. (I would describe the aide, but I was too busy writing down his had jokes to notice what he looked like.)

Paul Cohen—whom I do remember as a pleasant, heavy-set young man with dark hair—took pity on me at this point. “You know, Jerry raised the funds that built the Institute for Muscle Diseases on East 71st Street. It’s the only institute of its kind in the world. and they have a corner- stone there that identifies it as ‘The House That Jerry Built.’ You ought to put that in your story.”

Just then we passed the Cathedral of St. John the Divine. A group of boys were playing soccer in the yard next door.

“Stop the bus! Stop the bus!’’ Jerry yelled. “I wanna play hail!” The bus ground to a halt and he ran to the door. “Lemme kick the ball!” he shouted to the kids. But he didn’t leave the bus. The boys all ran up to the fence and waved. A candy man hurried up to the bus and Jerry said. “Gimme some almonds.” Only he pronounced them “ammans,” with an imitation Bronx accent.

“I’m an actor, Jerry,” said the candy man, who must have been at least seventy.

“I know it areddy,” Jerry replied. “I saw ya in ‘King Lear.’ ” The candy man laughed. Jerry waved goodbye to him and the kids and we were on our way again.

At Manhattan College, Jerry did play ball. He insisted on spending fifteen, twenty minutes tossing a football around with an appreciative group of young college men. When one of them told him they were there on a religious retreat. Jerry asked: “Oh—is that like Passover?” They all laughed and he went clambering down a long flight of stairs to the auditorium door. He entered and gave his speech to another group of workers.

For the first time, I heard him mention muscular dystrophy in a highly personal manner. “I’m a father of five sons,” he said, “and I know the feeling of having them just ill with bronchitis. I can imagine the feelings of those who have a child with muscular dystrophy . . . .” And he closed his speech in a rather strange way. “Helping 135,000 crippled childen is very depressing,” he admitted. “I can only thank you for what you’re doing and what you’re going to do.” Then. as a small boy approached the stage to take his picture, he smiled tenderly at the boy and said, “Is that me in the camera? Oh, that’s a monkey bird.” And he made a funny face.

With that he was off the stage and bounding up the long flight of steps toward the bus.

Halfway up the stairs he suddenly stopped, caught his breath and waited for a minute, an oddly surprised expression on his face. Then, very slowly, he continued on up, holding onto both railings for support. His face was flushed red.

Back in the bus, he went through to the bedroom and lay out flat on his back. After a few moments I went in to see if he wanted to talk. He said, “Sid down. Let’s talk about anything except you-know-what.” His face was still slightly flushed.

I sat on the edge of the bed and asked, “Why do you work so hard? I know you’ve had a heart scare or two.”

“Because I love it. that’s why,” he said. “Because it’s my life. I have no use for people who say ‘I hate to work.’ That comes from untalented people.”

“What do you like best about your work?” I asked.

“Not being out of work,” he said seriously.

“You mean after all this time you still think about being unemployed?” I asked, and he nodded.

“I wanted to he a movie star when I was a kid,” he continued. “You know what happened. Now what’s wrong with that? When some people hear me say I like being a star, they’re shocked. ‘You mean you say that publicly?’ they ask. But you know something? They’re the ones who are most impressed. John Wayne came into my dressing room recently and sprawled around and talked. I thought, ‘John Wayne comes in to see me!’ I’m impressed. What’s wrong with that?”

“But how do you keep up the pace— writing, directing and starring in your own movies, plus all this work for muscular dystrophy?” I asked.

“The doctor’s been helping me with vitamin B shots,” Jerry said.

“Does the doctor try to slow you down?”

“He knows better,” Jerry laughed. “As I said, I like to work. I’m the only guy who takes four weeks’ vacation in two days. Actually, once a year I go away with Patti and the boys or else they stomp on me. And I spend every weekend relaxing with them at home. That keeps me going for the rest of the week.”

Suddenly he jumped up. pulled a hat down low over his ears and ran into the other room. He gave a stupefied stare, reached into his pocket and pulled out a pair of horribly crooked false teeth. He slipped them into his mouth, looked at us and asked, “Hey, where’s my caps? I gotta make a public appearance!” We all laughed. and the bus pulled up to a stop in front of Roosevelt High in the Bronx. As usual. a crowd quickly clustered in front of the picture window and looked in at Jerry. He waved genially at them, all the time making wildly insulting re- marks which they couldn’t hear.

Jerry’s aide enthused, “The one thing he has in common with these kids is that he hasn’t learned to repress his emotions. He’s a baby. That’s why they love him—he’s a baby.”

Then we all trooped into the school auditorium and Jerry gave another pep talk. This time his manner was more subdued—possibly because a line of muscular dystrophy victims in wheel chairs sat at the front of the auditorium. Their ages ranged from five or six to sixteen. Some of them were hunched down in their chairs, unable to hold themselves erect. But they all beamed when Jerry would crack a joke.

The biggest laugh came when a little girl asked Jerry, “Do you ever give any money for dystrophy yourself, Mr. Lewis?”

His reply: “Yes, honey, I have. In fact, I wanna get a little back. I’m empty today!” The audience roared.

But he closed his speech with this reminder: “The things you keep, you lose. The things you give away, you keep forever.”

Back at the bus I told Jerry goodbye. I felt I had to get the rest of his story from others. He was heading out to Long Island for an all-evening tour of rallies that wouldn‘t get him back to Manhattan until around midnight.

“Sorry I couldn’t tell you more,” he said quietly. “But I just don’t think I should talk about it. It was nice having you along, though. And any time you want to talk about show business or anything like that. just let me know.”

The following week I dropped by the institute for Muscle Research—“The House That Jerry Built”—and talked to some of the doctors there. One told me a story that Jerry himself would never have told.

“Jerry got some information a few years ago that a little boy with muscular dystrophy was going to celebrate his ninth birthday the next day,” the doctor began. “The child was in Lakeview Sanitarium near Boston. His father had murdered his mother and was doing life in the Massachusetts penitentiary. The boy was pretty far gone, and they knew that this birthday would be his last. The authorities would never divulge his name—they just called him Little Boy Blue. He was a great fan of Jerry’s, and loved to watch him on TV.

“When Jerry heard about the child, he said. ‘We’ll put on a TV show exclusively for this boy.’ He called General Sarnoff at NBC and had a closed TV circuit set up between Los Angeles and the sanitarium in Massachusetts. They had to send mobile units up there from New York.

“In less than twenty-four hours, Jerry assembled an array of talent that would have cost a million dollars if any sponsor had to pay for them: Dinah Shore, Hugh O’Brian, Eddie Cantor, George Gobel, Eddie Fisher and a twenty-eight-piece band. They helped Jerry put on a ninety-minute show that nobody in the country saw except that one kid and the people watching in his room. Jerry had sent the boy a TV set and they had a big birthday cake for him. It was a birthday like no kid ever had before or since.”

An office worker at the institute revealed that Jerry has raised $15.000.000 for muscular dystrophy research and care in the past ten years. “And you know,” he said, “I know for a fact that Jerry spends some part of every day of his life working for dystrophy.” This was a big revelation.

A nurse told me another story about Jerry’s concern for muscular dystrophy victims. “A teenage boy in Miami Beach, suffering terrible agony from muscular dystrophy, wrote Jerry a letter not long ago. He told him that as a sufferer who would die soon of dystrophy, he had great admiration for the magnificent work Jerry was doing in helping the search for the cause and cure of the disease. Well, Jerry took to phoning this boy every week, and writing to him frequently. Once he went to Miami and visited him.

“A few months later, Jerry did a TV show from the Hollywood Bowl. Just before he went on the air, he phoned the boy and said, “When I finished my number I’m going to walk up to the camera and wink. And nobody in the world will know what it’s for except you and me. That wink is for you.’

“After the show, Jerry phoned to ask his young friend how he’d enjoyed the secret signal. The voice that answered was not a familiar one. Jerry asked to speak to the boy. The woman hesitated slightly before she said no, he couldn’t. So Jerry asked for the boy’s mother.

“ ‘I’m sorry, Mr. Lewis,’ she said, ‘but—my sister can’t talk to anyone—not even you. Her boy—just died.’

“Jerry was stunned, silent.

“ ‘Mr. Lewis,’ the aunt said, and her voice broke, ‘it was as if you said goodbye to him. He was watching the show, and he was so happy when you gave him the secret wink—then he lay back on his pillow and closed his eyes. And that was it.’ ” So now I knew some of the things Jerry had done to fight muscular dystrophy. And I was beginning to have an inkling of what drove him to give it so much of himself. If I could talk to someone who knew him very well. I might know if my theory was right.

Luckily I had some assignments in Hollywood, so I dropped by Paramount Pictures to talk to Jack Keller. Jack has handled Jerry’s publicity for many years.

“I keep telling him that more publicity would help his work for dystrophy,” Keller said, “but he won’t say any more than he’s told you. It’s a thing with him.”

“Do you know what got him interested in dystrophy?” I asked.

“Yes,” he said. “But he’s asked me not to tell. So I’m sorry, but I can’t.”

“Will you teli me this much?” I asked. “Has anybody in his family ever had dystrophy?”

“No—nobody ever has,” he said firmly.

“Did he perhaps get into the work for publicity, and then realize what a wonderful cause it was and stay with it?”

“Absolutely not. There’re hundreds of easier ways for him to get favorable publicity.”

“I thought as much,” I said. “Now let me tell you what I’ve really come to believe. I think Jerry’s got the feeling that he won’t live too long—because of his heart scare and other things. I think that’s why he feels he has to hurry if he’s going to get everything done that he wants to do—both in his career and in his work for dystrophy.

“And finally, I think he believes the only way to keep his life is to give it away—just as he implied when I saw him talking to those volunteers in the Bronx. By giving pieces of his life to everyone he meets— whether it’s just by telling a joke, or making a funny face or working twenty-one hours a day for dystrophy—by doing this, he feels that maybe he’ll live on in their lives. Or, if they don’t have too long to live, in their spirits. And as for those who wont live too long—the muscular dystrophy children—he identifies with them completely. Like them, he’s a little lost kid who’ll never grow up.”

“Well?” Keller asked.

“Well, what?” I asked.

“What are you standing around waiting for? You’re the only one who’s figured out the true story for himself, without being told. I think you’re entitled to write it.”

And that’s why I have.

—JAMES GREGORY

See Jerry in “It’s Only Money,” Par.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1963