“We could choose any baby . . . and picked you.”—Earl Holliman

“I was four years old,” Earl Holliman tells you, “and I remember I got two Christmas presents. One was some kind of a toy; my father had carved it himself, I think.

The other was a present I’ll never forget. My mother gave it to me—that is, the woman I call my mother. She sat me on her knee and said she was going to tell me a beautiful story,” Earl recalls, “and to me it was: How two people wanted a boy more than anything in the world, but couldn’t have one. How they hunted all over the country with empty hearts and finally found a boy they wanted more than any boy in the world. How that boy made them happy and grateful and glad.

‘And that boy’ she ended, ‘was you!’ I begged for that story every Christmas after that for a long time—it was my best Christmas present—and to me it was as wonderful as the story of Jesus in the manger.

I grew up knowing I was adopted, appreciating it, loving my parents all the more for it and feeling specially blessed because of it.”

But Earl didn’t get a chance to grow up far before his world began to wobble . . . His world began to crumble in a Shreveport, Louisiana, jailhouse just nine years after that first Christmas story. Earl walked into the jail and knew that upstairs someplace, in that dark and cold building, his father was dying.

“But he never did anything wrong,” the boy assured himself, trying to quiet the fear grabbing his stomach, sitting on the hard oak bench, watching the cops walking in and out—and waiting for his mother to come back down from the jail infirmary.

“He’s in there because he’s so sick. Because there’s now where else for him to go.”

Earl knew how sick his dad was; he had lived with the terrifying sickness ever since an oil rig accident in Texas had injured his father, and resulted in epileptic fits that gradually chopped down the strong, kind man who had raised him. Then suddenly they were violent and steady—two hundred seizures that last jay. No charity hospital would take an acute case like that, and their money was one. The coroner suggested the jail. “At least he’ll get some medical care there,” he said.

When Earl’s mother came back, he saw her tears and knew his dad was dying. They rode home on the bus without saying much. An obscure line in the Shreveport paper announced their tragedy: H. E. HOLLIMAN DIED LAST NIGHT IN THE CITY JAIL. That Christmas, a couple of weeks later, they ate pork and beans, because beans cost only ten cents a sack.

Understandably, Christmas doesn’t mean quite the same thing to Earl Holliman as it does to most people. The holiday doesn’t recall a trip to grandma’s, a turkey feast and a cozy sense of well being and security. To Earl it’s still the season when the bottom dropped out of his boyhood. . . .

Right now Earl is living better than he has ever lived in his life. He has a cozy red-shingled house up in Laurel Canyon with a swimming pool. He has a maid to cook his meals, a new Oldsmobile HOLIDAY and a closet full of expensive clothes. He has a contract with Hal Wallis, money in the bank and some bluechip stocks. He has some old friends who aren’t big wheels in Hollywood and a lot of new ones who are. He has invitations to parties that never used to come.

An unwanted baby

But if anyone ever had a shaky start in life it was the unwanted baby delivered by a midwife in a sharecropper’s shack on September 11, 1928. Earl was the seventh child of an utterly destitute farmer. He weighed six pounds at birth but a week later was down to four, shrivelled and yellow with jaundice.

Then his father, his real father—died, and his real mother was left with six young children—and the sick infant Earl. And just one problem—where to get food for him.

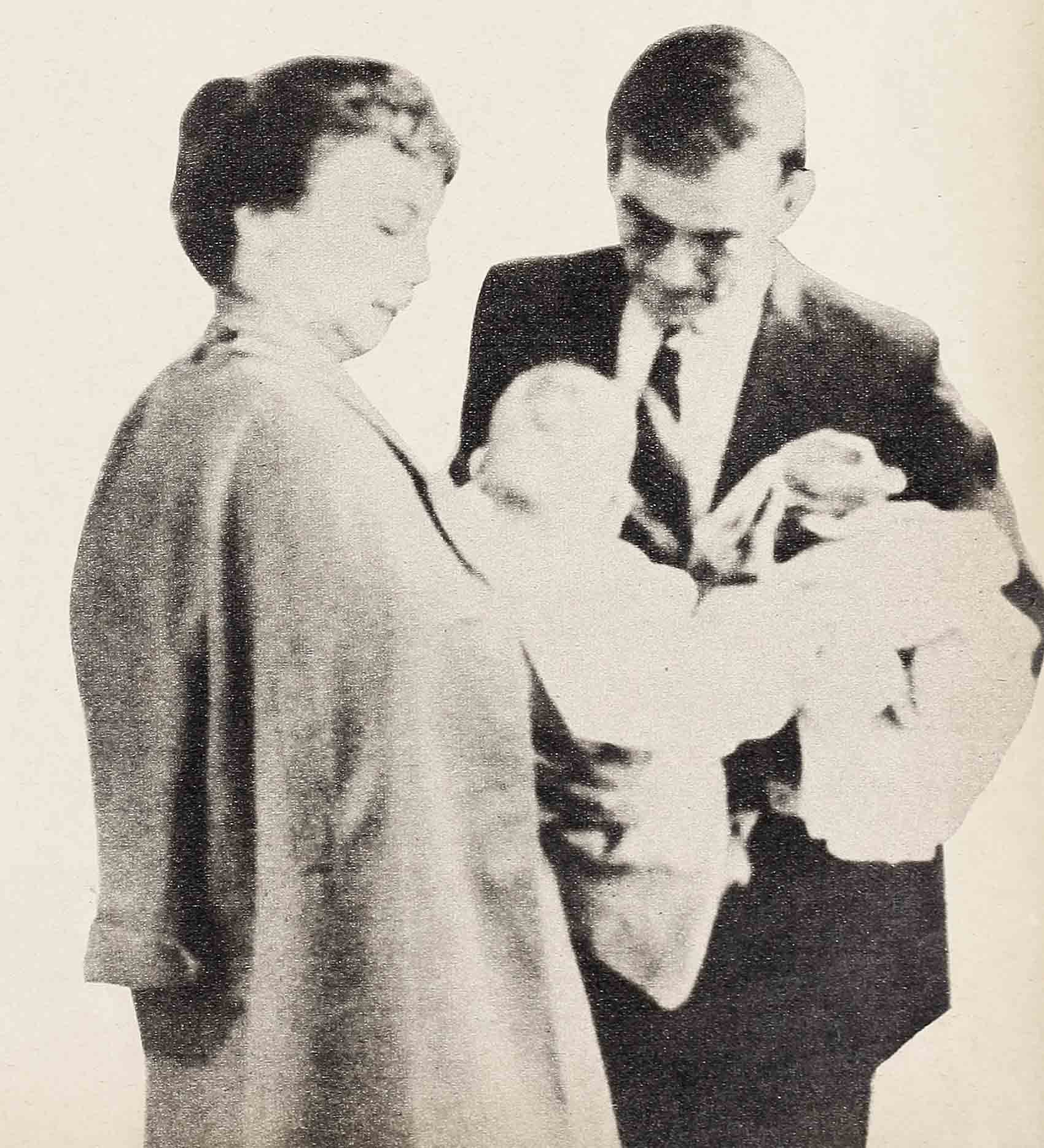

That’s when the Hollimans came into the life of weeks-old Earl.

Henry and Velma Holliman desperately yearned for a child, any child. Velma couldn’t have one, and adoption homes turned them down because an oil-field worker moved around too much. So they drove fifty miles and picked up the miserable waif in his flour-sack diaper—and listened to a backwoods doctor tell them, “You haven’t got a baby—you’ve just got a funeral expense!”

For a long time, it was touch and go. During his first year Earl almost died with double pneumonia. He could barely toddle when he fell against a tree root and smashed his nose. Two months later a little girl pushed him off a high porch and broke his leg. All his childhood he was puny and weak.

To make matters worse, the Hollimans moved around the Gulf oil country like nomads, wherever there was work for his adopted father as a driller. Earl remembers a score of “homes” including Jackson and Whitman, Mississippi—Kilgore, Crane and Kerrville, Texas—Odessa, Vivian, Mooringsport and Oil City, Louisiana. Usually he lived in paintless wooden dumps and sometimes in tents. And everywhere Earl faced the knuckled schoolyard challenge to a newcomer. It made him a lonely kid.

Armadillos, snakes and rats

Spending so much time alone, he made friends with animals—snakes, chickens and ducks—even adopted two scaly armadillos as pets. Once in Texas two white rats he prized escaped under the house, bred with local rodents, and city exterminators had to clean out the swarms.

With these dumb pals as with everything, Earl’s imagination worked overtime. The first movie he ever saw—in a shabby oil-town grind house—featured a train wreck. Afterwards Earl raced home, got out his toy train and loaded it with sowbug passengers. He set it rolling, then smashed the express with a rock and jumped in heroically to rescue the survivors. He told his mother, “I’m going to be a movie star when I grow up.”

The dream was born. . . .

To Velma Holliman’s credit, she nodded soberly, although the idea of that runty oil field tyke with his homely, freckled face ever becoming a Hollywood star must have seemed preposterous. She spread out her pack of cards and told his fortune: “Look here, Earl! Look what it says about your future. You’re going to be a movie star, sure enough!” After that he begged his fortune time and again. Just like he begged for the Christmas story year after year. And always she made the same rosy picture, and always he believed it implicitly.

Then there was the day of that accident and for too long there wasn’t time for dreams any more.

It happened at the Kilgore oil field. Henry Holliman was up on a catwalk when the derrick top fell and heavy machinery hit his head. A worker grabbed his feet as he fell and saved his life—but from then on it seemed like every job just led to a stretch in a hospital. After a while they declared him permanently and totally disabled and the oil company offered a small settlement. But until the settlement came through, the only steady income the Holliman family had was a $30 a month government pension from Henry’s World War I service. Earl picked cotton for a farmer and sold magazines to help out. For a while his mother ran a boarding house. When the money finally came, his Dad sank it hopefully in a small men’s furnishing store in Shreveport, but that soon went bust and the money with it. They moved to a fishing shack beside Caddo Lake on government land for a while, and it was a lucky day when the fish were biting. By then Henry Holliman couldn’t do anything. The epileptic fits had gotten worse and worse.

When his Aunt Ada died and left a small bequest, hopefully Henry took $800 and hammered together a little white house of their own. It was just about finished when the fits came in violent waves and then was that last horrible day in the Shreveport jail—just a couple of weeks before Christmas.

The little white home goes

After the funeral there was nothing left, except debts. The little house went for $400 to pay those. Earl and his Mom moved into a cheap room in Shreveport. Velma found a waitress’ job in an all-night cafe beside the bus depot for a dollar a day and two greasy meals. Earl found one next door in a magic shop for four dollars a week.

You might have called it a start in show business. Earl learned to demonstrate jokes and novelties and, when he’d mastered the ABC’s of sleight-of-hand, the proprietors let him assist in shows at the BARKSDALE AIR FORCE BASE nearby. When school started up again, he quit to usher nights at the STRAND THEATER for twenty-five cents an hour—and all the movies he could watch. But he was just falling asleep in classes, so when they offered him the job of head usher he quit school. And in a couple of weeks, he bought a brown, pin-stripe suit for $19.75. It was the first suit of clothes Earl had ever owned.

Earl figured he needed that suit, because he nursed a reckless plan. Watching pictures all day and half the night had brought his Hollywood yen to fever pitch. “I just had to go there and see the place,” he explains. “It was like a trip to Heaven for me.” To get the money, he moonlighted as a waiter in the restaurant where his mother worked—from eleven o’clock at night until eight in the morning, when Velma relieved him. When he had seventy dollars saved up, he put it inside his shoe and, lugging a cardboard suitcase hit the highway, headed West. He passed his fifteenth birthday in Fort Worth, Texas, on the way.

Hollywood the second time

Actually, Earl wasn’t so famished as he was deflated. He had spent the whole week pounding all over Hollywood, hunting movie stars. He never saw any. “Finally, I bought a two-bit pair of dark glasses hoping somebody would think I was one,” he grins. But the next time he saw Hollywood it was different. He was in the Navy.

Earl enlisted that January, still fifteen but lying about his age. They shot him right out to San Diego for boot training then up to Los Angeles for radio school. He had liberty every night. Those nights you could always find Apprentice Seaman Holliman at just one place, the HOLLYWOOD CANTEEN. “If there was a movie star I didn’t gawk at I don’t know who it could have been,” says Earl. To some of them he told his own dream. Always the advice he got was, Finish school and study acting before you try it.

So, Earl wasn’t too bugged when his mother told authorities how old he really was and the Navy kicked him out. She wanted him to come back and finish high school. Earl had the same idea now. And this time he had a better chance to stick.

Velma Holliman had remarried another oilfield worker and lived in Oil City. There was a place to live and a good high school. Credits earned in the Navy let Earl back in as a junior. He got a job afternoons in a grocery store and on weekends was a roustabout in the oil fields. He sailed through his junior year with straight A’s, next summer made good money at a Navy rocket plant in Arkansas, and as a senior showed what he could do with a little security behind him. That year Earl lettered in football, edited the yearbook, got elected class president and played the lead in the senior play. Shaking his shyness, he also went steady with a pretty brunette named Mary Ellen and even got voted the best dancer in school! When he graduated at seventeen, Earl Holliman won the AMERICAN LEGION BOYS’ MEDAL and a scholarship to LOUISANA STATE. He didn’t accept instead he re-enlisted in the Navy. Curiously, Earl figured that was the only way to learn to act.

It wasn’t quite as crazy as it sounds. Earl had a plan: two more years’ service, and he’d qualify for the GI bill. Then he could pick his own dramatic school, tuition paid and seventy-five dollars a month. It worked out even better than that. In Norfolk, Virginia, where he was based as a radio operator most of the time, the Norfolk Naval Theatre gave him a solid hitch up on acting experience. In that rankless group, captains and commanders often played bit parts. Seaman Holliman played leads. This time he came out of the Navy with two important assets: self confidence and his GI bill. Right away he put that to work at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA. But after a year he switched to Pasadena’s famous COMMUNITY PLAYHOUSE.

Hollywood the third time

For one reason, Earl wanted more practical acting experience, and the Playhouse is famous for that. For another, he knew it had always been a fast pipeline to Hollywood. The first part worked out dandy for Earl. “I played everything from Edipus Rex to Home Of The Brave,” he says, “and I learned plenty. But Hollywood scouts took one look at my face and looked right through me like a pane of glass.” Still, it was PLAYHOUSE contacts that indirectly channeled Earl to his movie break.

Earl had to quit right before graduation when his GI bill ran out. He took a job as template maker at NORTH AMERICAN AVIATION, then fabricated oxygen therapy gadgets at a Beverly Hills factory. After work he’d hustle to agents’ offices, but no matter how he dolled himself up they’d only dust him off with that too homelybit. The only way he could get inside a studio was to work a dodge he’d learned from resourceful characters at the PLAYHOUSE.

The trick was to show up at PARAMOUNT’S DeMille gate with a mop of hair and tell the guard, “I’ve got an appointment with Victor, the barber.” Lots of outsiders patronized Vic, so it was usually a fast wave-in. Hours later Earl Holliman would walk out the main gate, his head buzzing with the sights he’d seen.

One day, he bumped into a PLAYHOUSE classmate, Irene Martin, who’d been picked for PARAMOUNT’S Golden Circle. Irene came through for the old school ties with an introduction to the casting office and a build-up. After weeks of steady hounding they gave Earl a one-day bit to get rid of him. He was an elevator boy in a Martin and Lewis romp, Scared Stiff. “Which,” Earl admits, “I certainly was.”

Haircut to success

But, turning in his uniform, Earl ran into another casting director, collecting extras for Marines in The Girls Of Pleasure Island. The easiest way to lose Holliman was to say, “Okay, okay—get a GI haircut and I’ll give you another day’s work.” So, Earl finally climbed into Victor’s barber chair. When he stepped down and looked in the glass he was sure his budding career was ruined.

Earl’s hair is silky-fine, and on him the GI came out a comical fringe of bangs. “I looked like something escaped from the zoo,” says Earl. “With my already obvious handicaps I figured that was all I needed.”

When the director spotted him he laughed. After that, whenever he needed a funny-looking Marine he crooked his finger at Earl.

Earl Holliman didn’t star or even play leads, and sometimes, as he’s said, the characters he did play weren’t too attractive. He didn’t get a chance at one romantic part until his last, Don’t Go Near The Water. But whether he’s been a hick or a hoodlum, Earl Holliman has always been a scene stealer. And it isn’t all because of his haircut. He takes his job very seriously.

As a matter of fact, Earl wore curls in The Rainmaker, his favorite, which he’s seen ten times to study his faults. The New York preview, with Broadway critics and the Paramount brass assembled, was the biggest night of his life that far. Yet, he slipped away and sat by himself in the packed Lexington theatre to get an honest audience reaction. He got a stinger.

The writer razzed him

Two girls sat next to him, and one razzed him unmercifully every time he came on the screen. “What a silly character,” she scoffed. “Isn’t he terrible? Did you ever see such a stupid actor?” And so on.

When the lights went up, Earl couldn’t resist saying, “I’m sorry you didn’t like me in the picture. I’m Earl Holliman.”

“Oh!” gasped his critic, turning several shades of pink. “I knew this would happen to me someday.” Funny part was, next morning she called Earl’s hotel. She said she was a writer and wanted to do a story on him!

Some have it easy and some have it rough—on the road to Hollywood or anywhere else. Earl Holliman has had it very rough ever since he was born, a sickly baby in the swamps of Louisiana, given away to strangers because his own parents couldn’t afford to feed him.

Growing up, he’s been sick and he’s been scared, hungry and poor, lonesome and sad, disappointed and snubbed. He’s had to make his own living since he was fourteen. Yet, this December 25th Earl will give thanks along with everyone else—as he does most of the days of the year. “I’m lucky,” he says in his soft, serious voice, with just a hint of a Southern drawl. “Sure, I’ve had to scramble. But I’m glad I did. Maybe I wouldn’t appreciate what I’ve got now if I hadn’t.”

What Earl has now is what he has wanted all his life—a job acting in the movies. It’s a pretty good job and Earl Holliman is a pretty “good actor. Last year, after Jimmy in The Rainmaker, there were Academy Award noises and the Foreign Press made it official by handing Earl their BEST SUPPORTING ACTOR trophy. Coming out of the COCOANUT GROVE the night he got it Earl felt a tap on his shoulder and, turning around, faced Sir Laurence Olivier.

“I just wanted to tell you,” Olivier said, “that my wife and I saw your picture in London and we thought you were great.” Earl could barely stammer, “Th-thanks,” but he felt like Sir Larry did when the King dubbed him knight.

Yes, this December 25th, Earl will give thanks . . .

THE END

—BY KIRTLEY BASKETTE

Watch for Earl in MGM’s DON’T GO NEAR THE WATER and Paramount’s HOT SPELL.

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1957