The Richest Bum In Town—Robert Mitchum

“I’ve been married sixteen years,” Robert Mitchum announced on his last wedding anniversary. Then he smiled, wearily as always, for he was smiling at himself. “That’s quite a record for a bum.”

A glance at the complete record, however, is even more amazing—for a self-styled bum. Here is a man who has not only been married sixteen years, but to the same woman. Bob has three children, four cars. and one home complete with swimming pool. What’s more, he’s a steady man, having been gainfully employed in the same business for thirteen years. And although he claims he has no drive, Bob started at the bottom of that business and worked his way up until he is now his own boss.

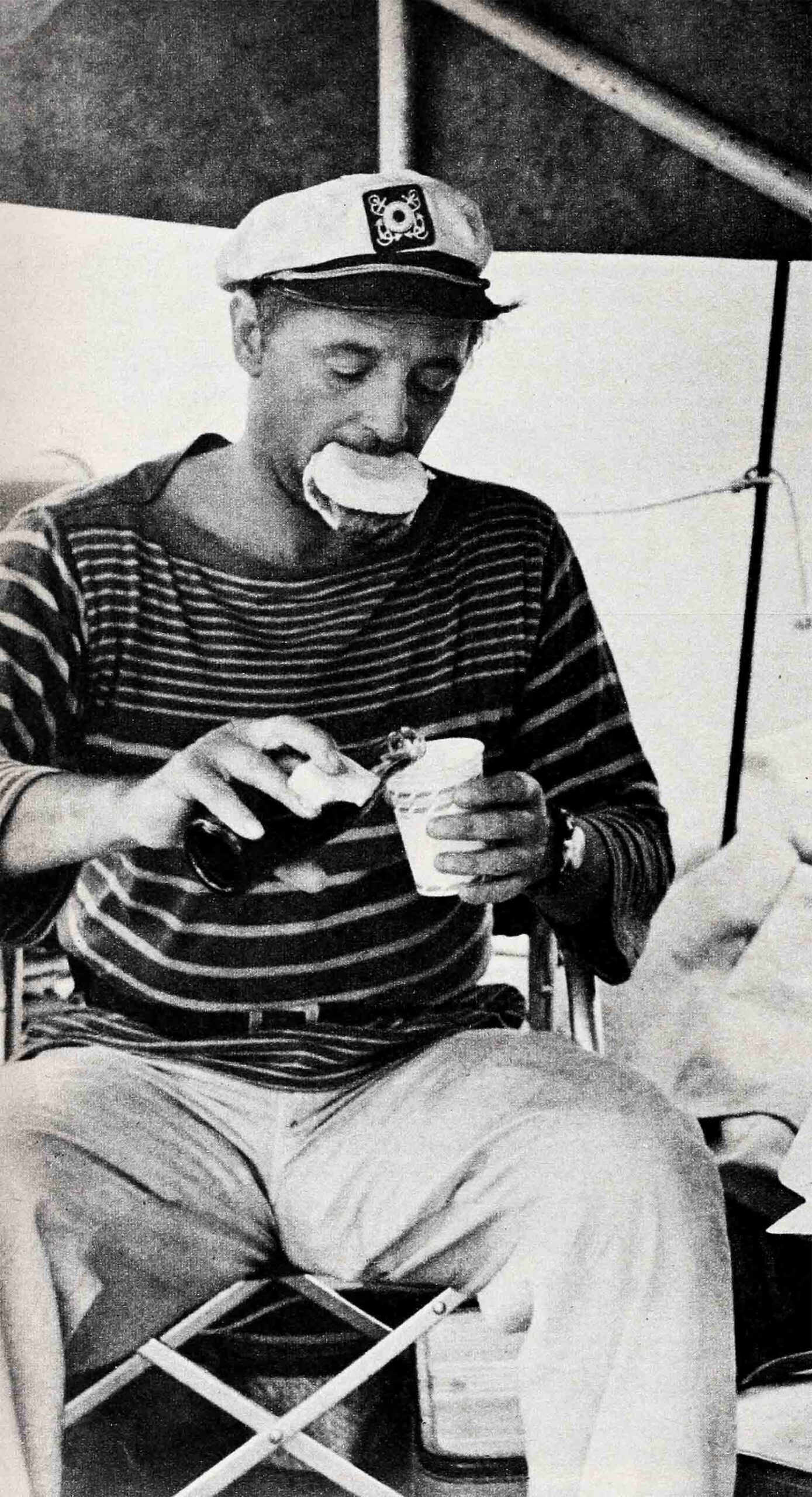

He also claims he’s lazy, and he says it as lackadaisically as any dyed-in-the-wool bum. The record, however, shows that in one typical year Bob made three pictures, then spent seventy-six straight “Not as a Stranger.” Since then, although he announced that he was about to take a year off, he has starred in one film after another: “Man with the Gun,” “Foreign Intrigue,” “Bandido,” and “Fire Down Below.” He has scarcely taken a month off, let alone a year, and he is now busy making his hundred-and-tenth motion picture.

Why does Bob work so hard? “I believe in restitution,” he says. “You’ve got to put back what you take out.”

But it’s more than work alone that distinguishes a man from a bum, it’s pride—and Bob Mitchum is one of the proudest men in Hollywood. He has never been in debt, “But,” he adds hastily, “there was one time I went in hock to Howard Hughes. But that was paid back a long time ago.”

And yet Bob, in spite of a record that any other man would be proud of, keeps calling himself a bum. He doesn’t tell you why he does this. In fact, he rarely stops to explain his remarks or even to answer direct questions. He simply thinks out loud, letting flow what he calls his “stream of consciousness.”

He often talks like a truckdriver and swears like a trooper. He acts the cynic, the tough businessman, the jaded playboy. However, in spite of all his experience as an actor, it’s an unconvincing performance that fools no one. For Bob Mitchum is a painfully articulate man who has not only lived harder than most men, but fought harder for understanding, searched harder for the truth. And if he calls himself a bum, it’s to sidetrack you from calling him something worse. For the truth is, Bob is a poet, and nowadays “them’s fightin’ words, son.”

The notion that anyone as big as Bob—or as rugged—might also be a poet sounds ridiculous. But Bob was hailed as “the finest young poet” of Bridgeport, Connecticut, and the hometown paper used to publish his works. The first was called, “A Chreestmus Pome,” but a later effort, written when Bob had finally learned to spell, was to prove prophetic:

“I seek adventure and I find too much.

Oh, if I were only rich,

I’d not be in this terrible ‘dutch’—

I’d not be in this ditch.”

In retrospect, it sounds funny, but it was serious when Bob wrote it. This was no youngster, dramatizing himself with pen and paper. The ditch was probably on the side of the road somewhere, far from home. The terrible “dutch” could well have been one of those awful jams a boy gets into when he’s bumming around the country, broke and hungry, and it seems he’s had enough adventure to last a lifetime. Except that the next day or the next time he has a full meal in his belly, he’s ready to start out again. There can never be enough adventure.

Before he was twenty-one, Bob had traveled in all forty-eight states. He never finished high school, but he got a thorough education riding the rods, living in hobo camps, and dodging the yard bulls in railroad yards. It was good experience for his writing. Even today, he refers to the time he was in a Georgia chain gang—his only crime being that he was broke. But even then he was not a bum asking for handouts. He worked—in stores, filling stations, amusement piers. He took jobs as a farmhand, beach boy, truckdriver, stevedore, bouncer, housepainter, steel worker, track layer, cement mixer, day laborer, quarryman, dancer, and contact man for an astrologer. He was even a boxer once but soon gave it up. “I never want to hurt anyone.”

Eventually, acting proved to be his best bet. Bob had joined the Long Beach Theatre Guild, a little theatre his sister was interested in. And although he was writing some scripts for CBS, occasionally he also worked “in front”—meaning in front of the microphone. An agent, hearing him in a radio version of Gorki’s “Lower Depths,” and noting his physique, told Bob to look him up if he ever wanted to go into pictures. Bob wasn’t interested. On March 16, 1940, he had married Dorothy, the girl he had been going steady with ever since he was sixteen. If he was to be a family man, he would need a more stable line of work than movies could offer. And by the time the first baby was on the way, Bob was working at Lockheed. After a year at the airplane factory, however, a doctor advised him to quit.

“I was on the night shift and never got any sleep,” Bob explains. “I thought I was going blind.”

His family suggested that he try films “since he was in Hollywood anyway.” Remembering the agent who had once offered to help, Bob went to him and broke into pictures doing bit parts.

“It was a wonderful experience because I made a number of friends in the business among writers, directors and producers.” Bob always jumped at the chance of meeting new people. “There were a couple of directors who would fit me in anywhere. Sometimes there was nothing left to play but an old Chinese laundryman, and I’d take it. I got to play everything but midgets and women.”

It was valuable experience for a character actor, which is what Bob considered himself. But then came Ernie Pyle’s “The Story of GI Joe.” Bob was just about perfect as the battle-fatigued officer who knew the futility of war but was too busy taking care of his men to make speeches about it. The world-weary young actor could understand Lieutenant Walker’s sensitivity, his cynical disillusionment. The way he felt about war was the way Bob felt about life. And for the first time, the screen captured something of Bob Mitchum himself.

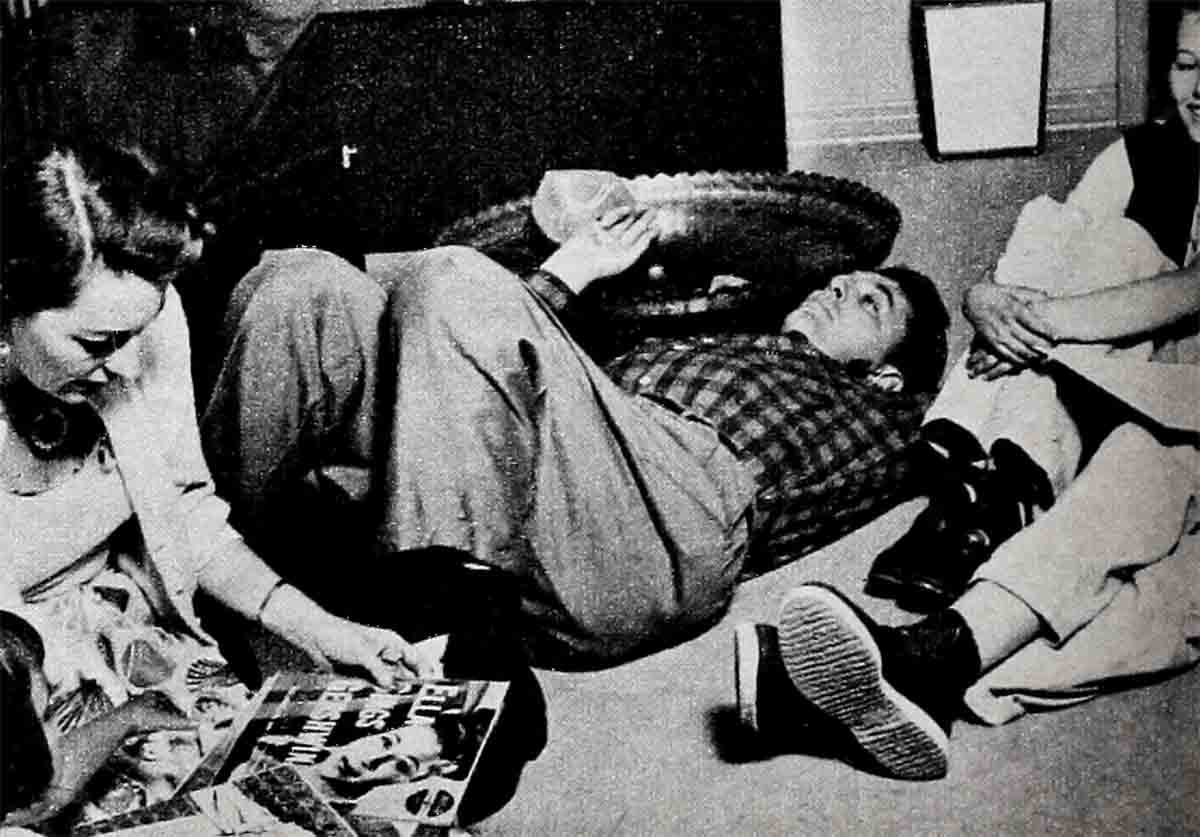

But for Bob Mitchum himself, “It was a day of great embarrassment. Suddenly,” he remarks with typical self-deprecation, “I was a trueblue Harold the Hero.” His reward was stardom, and a succession of what he calls “Elmer the Excellent” roles. But Elmer the Excellent was making five thousand dollars a week. The Mitchums moved into a home in Mandeville Canyon—not a movie star’s palace, but the kind of comfortable home in which real families are raised. Bob was able to give his three children all the material things that he himself had missed as a boy. But most of all, he was free to indulge his passion for giving gifts. One time, when Dottie Mitchum flew to Dallas, Bob had a surprise birthday gift waiting for her—a brand-new car all wrapped up in cellophane. And recently, on a trip to New York, he spent hours going from shop to shop, trying to find just the right amethyst bracelet to go with the ring he had bought Dottie in Mexico. For his two sons, there was “a thousand dollars’ worth of fishing equipment.” As for baby Petrine—she can have the whole world!

Bob can’t seem to buy enough presents for his family, which makes it appear a: if he is trying to make up for the fact that there’s nothing he really wants himself. He’s used to traveling light. If tan gabardine suit is Rob’s trademark in pictures, it’s because when he was start ing out, that’s all he owned. Even today, he has only three suits. “It’s just as well, he explains. “There wouldn’t be room for more. The only thing that’s mine in the house is a saxophone I’ve got hanging up on the wall. I only take it down on Christmas, New Year’s, and birthdays when I play such appropriate numbers as ‘Silent Night,’ ‘Auld Lang Syne,’ and ‘Happy Birthday to You.’ Then I’ve got—well, not a desk, but one drawer of it.”

It he was to feel crowded in his house, he was to feel even more crowded in Hollywood itself. “If only I hadn’t dropped my pencil at CBS or my wrench at Lockheed!” he’d sigh, wondering how he ever got mixed up in such a crazy business as motion pictures. He early earned himself a reputation as a “Hollywood rebel,” but he was not exactly a rebel without a cause. “I’m against everything phony,” he has railed, but he never included in that the actors before the scenes or the technicians behind them. He was referring to “executives justifying their salaries.” One of his chief complaints, for instance, was inefficiency. “I hate waste,” he insists. “I was taught to eat everything on the plate.”

In spite of Bob’s outspokenness, however, executives invariably forgave him because his pictures invariably made money. And everyone else loved him. He was fun. There was never a dull moment around Bob, and he’d literally give you the shirt off his back. And yet, he insists, “I have no friends.” He considers this for a minute, then adds, “I have no enemies either, and that’s bad.

“Actually,” Bob says, “I’m most at home with the grips—you know, the old-timers who have been working behind the scenes in the studios since Wallace Beery was a juvenile. They like me.” And he interrupts to show you a thousand-dollar watch. “Look,” he says, still touched. still incredulous. “Even in Europe, the grips pitched in to buy me this after we finished ‘Foreign Intrigue.’” But most important, to Bob, the film crews not only like him, they understand him. “They know I talk a stream of consciousness and sometimes I fall flat on my face.”

But the public was to know it, too. For we live in a world where our bad—not our good—behavior makes the headlines Several years ago, the papers had a field day with Bob, not caring whether they hurt him, his family, or his career. Bot made no excuses, but quietly went about living it down. He understood that a star has to accept headlines as “just one more of the joys of success.” But oh, what a terrible “dutch”!

“If I were only rich,” the finest young poet of Bridgeport had once cried out. Now he was. Only, something was wrong And five thousand dollars a week was not the answer to life. The trouble was that success had come too easily, and so it had no meaning. Bob blames it on the accident of his physique. But he also had a personality that intrigued the public so Hollywood used him as “a commodity,” a brand name, packaged in the same tan gabardine suit and served up in the same hackneyed roles. All Bob had to do was to memorize the lines, and even that came easy. “I’m a quick study,” he claims. “The first day of shooting on a new picture, I’ll walk on the set and ask: ‘What’s the script?’ Everyone goes crazy then, thinking I don’t know my part. And the other actors complain that they’ve been up all night memorizing their lines. But I can get them right there on the set, with one quick reading.”

Bob admits that he had “arrived at the point of just strolling through pictures.” The public liked him that way so the studio kept him that way—and the studio had him under a ten-year contract. But inside that “physique” there was a restless spirit, and behind those droopy eyes there was an active imagination.

Like many another American with a problem to solve, there was a time when Bob would jump in his car and just drive somewhere, anywhere. Only in his case, somewhere was liable to be any one of the forty-eight states, and anywhere was preferably a little village with a population of seventy-five or less.

“I’d come riding into town,” Bob recalls, “like the Lone Ranger, and sure enough, someone would come up to me and ask: ‘Ain’t you that feller who plays in them Westerns?’ ‘Yep,’ I’d say, and like as not he’d ask me to join his family for supper, and I’d spend the whole night just talking to them.”

In a sense, it was like harking back to the days of his youth when he went bumming around the country. Only then he was searching for adventure. Now he was one slightly world-weary motion-picture star trying to find some meaning in life. He had lived too hard ever to recapture innocence. Had he also made things so complicated that he could never return to simplicity?

He envied the bums, those “knights of the road,” their simple, carefree life. They were free of care, yes, but only because they had never assumed the responsibility for anyone else but themselves. And if they hadn’t done that, what could they possibly know of love? And what kind of life was it—always to live apart, looking at happiness through the lighted windows of someone else’s house? And what was Bob doing himself, riding into strange towns, when he had a house of his own to go to? He should be making his own happiness in it. For his life might not have any meaning to it, but at least it had love.

Although Bob still as a bum, it’s more a habit now than an accusation. For there has been a change. He takes pride in his work, now that he’s no longer under contract to one studio but can pick and choose his own roles. What’s more, he’s turned producer, which allows him to use up some of his creative energies.

He’s still restless, and ready to take a trip at the drop of a hat, if he had a hat. But now, he seldom makes a trip alone. There’s little Petrine who likes to be driven along the beach road so she can look at the ocean. Then there are the hunting and fishing trips he likes to take with the two boys. But best of all, there are the trips all over the world—to London, Paris, Trinidad—usually on location for a picture, and always with Dottie at his side. They are very close, and she loves him exactly as he is.

“And for me,” Bob says again, with a wicked sidelong grin, “that’s quite a record, too.”

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1956