Man Without An Axe—James Cagney

If the reward of mankind’s suffering and the object of reform is to make people happier, then Jimmy Cagney should be held up as an example to all. He is lucky, successful, talented, popular, healthy and rich, and in spite of it all has a high I.Q. He has no theory, philosophy or axe to grind. He is not jealous, ambitious, or pretentious. Actually, he is, like quite a few of the very good ones, a wee bit shy.

Many men, in order to live a quiet tranquil life, have had to shun civilization and go to the wilderness, even if they only got about as far from home as one could bat a ball. Cagney has found no necessity for self-imposed seclusion. He does not find modem life too complicated, although with his energy he sometimes makes it a little more complicated than usual. He is that rarest of creatures, a playboy who works like a Trojan as well. He even finds time to read, and do his bit for the angels in political campaigns and public controversies.

After twenty years he is still married, most comfortably, to “Billy” Vernon, whom he met in vaudeville, and is the kind of a husband who likes to take his kids to the circus—as if that were necessary. Cagney going to a circus is likely to result in a draw. But don’t misunderstand me. He is not the practical joker who gives hotfoots or calls, as Mr. Fish, and leaves the number of the Aquarium on April Fool’s Day.

East Side New York must be an exceptionally whole- some background in which to raise children who want to go into the motion-picture industry, what with John Garfield, Edward G. Robinson and Paul Muni, to mention only a few. Of course, Jim Cagney sold papers. It would be easier to count the Americans who had not sold papers than those who have. Also, most of them fought against bullies for their corner and all of those on record won and held their ground. The losers must have gone out of public life. Cagney never got as far as reform school, although no doubt he deserved it. He managed to finish high school and stuck one year at Columbia, after which the call of show business was stronger than that of Athena, the Goddess of Learning.

What sets Jimmy apart from most of the promising men who spent their childhood on the sidewalks of New York is the fact that he has not remained, essentially, a city man. The shore home he recently sold in Massachusetts was a model of what a seaside cottage should be, modern enough to be comfortable yet with all the beauty and sturdy usefulness of the early days of America.

His two-masted schooner, named The Martha’s Vineyard, is one of the trimmest sailing craft afloat, with perfect lines, the seaworthiness that the old-time Down East shipbuilders could impart, and it has never figured in any goings-on that would be better suited to night clubs or boudoirs. Jimmy uses his craft for sailing and he can do a first-rate job of sailing it himself.

That nautical ability, however, does not drive Cagney to the other extreme. He does not pilot The Martha’s Vineyard to Tahiti, Nome or Zanzibar. His cruises are moderate, in length and intensity, and if the weather blows up pert, he heads for shore, which is usually not far from sight. He has never had to quell mutiny, fight off pirates, or even rim the rum blockade. His crew likes him; and the sea marauders, having seen him knock the blocks off men (and even a few women) on the screen, they have a healthy respect for him.

Hearty man that he is, Cagney eats and drinks moderately. That is about as far as he goes with his self-control, cmd surely that is not offensive. His appetite is brisk. He sees his friends go after beef-steaks (in steak years), and a few of his cronies are among the first-string heavyweight drinkers of the modern world. But Jim takes it easy at table because of his one vanity, his waistline.

I have said that he is not the conventional city type. In no way is this more pronounced than in his love and understanding of animals. Just now he has five horses, two goats, a dog, a couple of cats and a wonderful rat he keeps in a cage in his office and lets run loose whenever he is there to protect him. This rat became attached to Cagney while both were involved in the shooting of some picture or other and after the film was in the can, refused to go back to his former habitats but followed Jimmy around. Jimmy soon learned what rats needed to make them happy, in the way of food, privacy, companionship, etc., and his pet rat will probably live to be a hundred or so.

His children, Jimmy Jr., aged four, and Katherine (nicknamed “Casey” for her initials, K.C) like animals, too, although they are very much at home in New York, Hollywood, or any place between.

“I am naturally lazy,” Cagney told me. “I don’t like to work as my brothers do.”

He was referring to “Doctor Harry” and “Doctor Ed,” both Hollywood general practitioners, and not by any means to Brother Bill, his producer and partner. Bill dislikes work as heartily as Jimmy says he does. Bill’s function in the family scheme is to do Jimmy’s worrying for him. Perhaps that accounts for Jimmy’s notoriously carefree attitude toward life.

Imagine a New York East Sider journeying each year to Indiana, voluntarily, to attend and participate in the Hamiltonian sulky races there. Jim drives a mean sulky, and is getting better all the time. A surprising number of things he does well. He even showed a taste for ballet dancing once and only by the greatest effort of will, for the sake of his family, gave it up.

All the Cagneys are somewhat self-consciously Irish. They don’t exactly get over the chalk line into the corny side, but the mention of Erin, or any suggestion, of it six or seven times removed, starts a twinkle in their eyes and the conscientious little sigh that goes with it. It is not a rare sight in Hollywood to see Jimmy and Bill Cagney around a table with such non-Latin characters as Spencer Tracy, Pat O’Brien, Frank McHugh, George Murphy and Frank Morgan. What is on the table is neither here nor there. And at most of it, Jimmy Cagney looks with longing and envious eyes.

Jimmy’s wife quit the stage the moment she said “I do,” and has had no hankering for it since. She is a truly domestic woman. Her home and family absorb all her interest, and she would not have it otherwise. She does not go in for Culture, with the capital “C,” or Society with the capital “S.” As for Jimmy’s “art,” the least said about it the better, from her point of view.

Throughout the studios where he has worked, Cagney is known as the most cooperative star in the business. After twenty years in pictures, he had not played a single role that is worthy of his talent and personality. In his own mind, “Yankee Doodle Dandy” stands out as his best, and it was surely a very brisk and entertaining picture, but, to me, Cagney is essentially a modern man and should have given us some authentic and valuable pictures of his own time. It is not right that his masterpiece should be the impersonation of a character from the preceding generation. “Studs Lonigan,” after all, was written by a distinguished Irishman, James T. Farrell, and if it were adapted for the screen, Cagney could really go to town.

There are so many unexpected sides to Cagney’s character and tastes that his friends are constantly being surprised. One day he will come into the studio and say: “I read a great book last night. It kept me awake until dawn.” The book will turn out to be Homer’s “Iliad.”

He thinks Ingrid Bergman is “tops” as an actress.

His favorite modern poet is Stephen Vincent Benet.

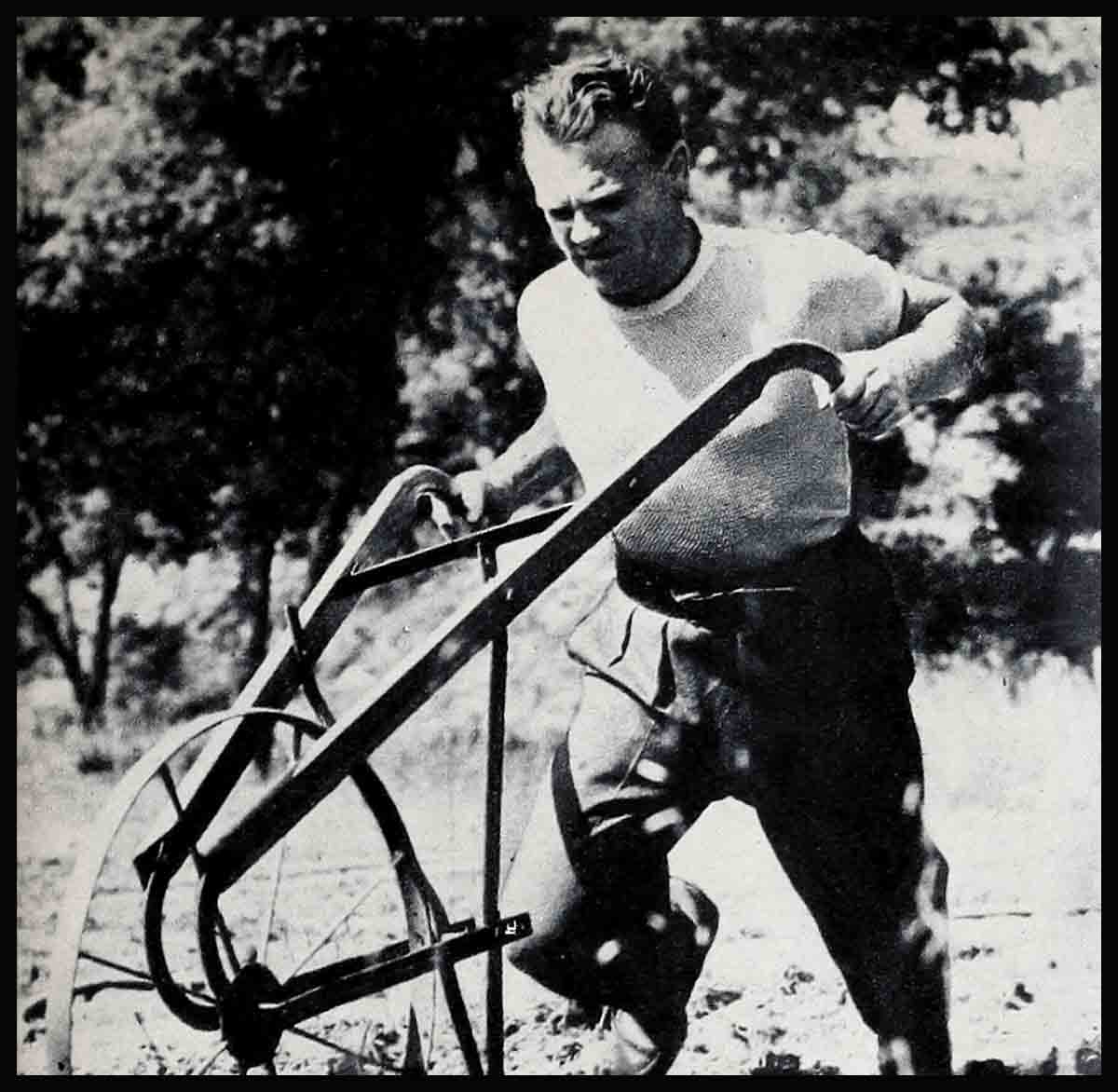

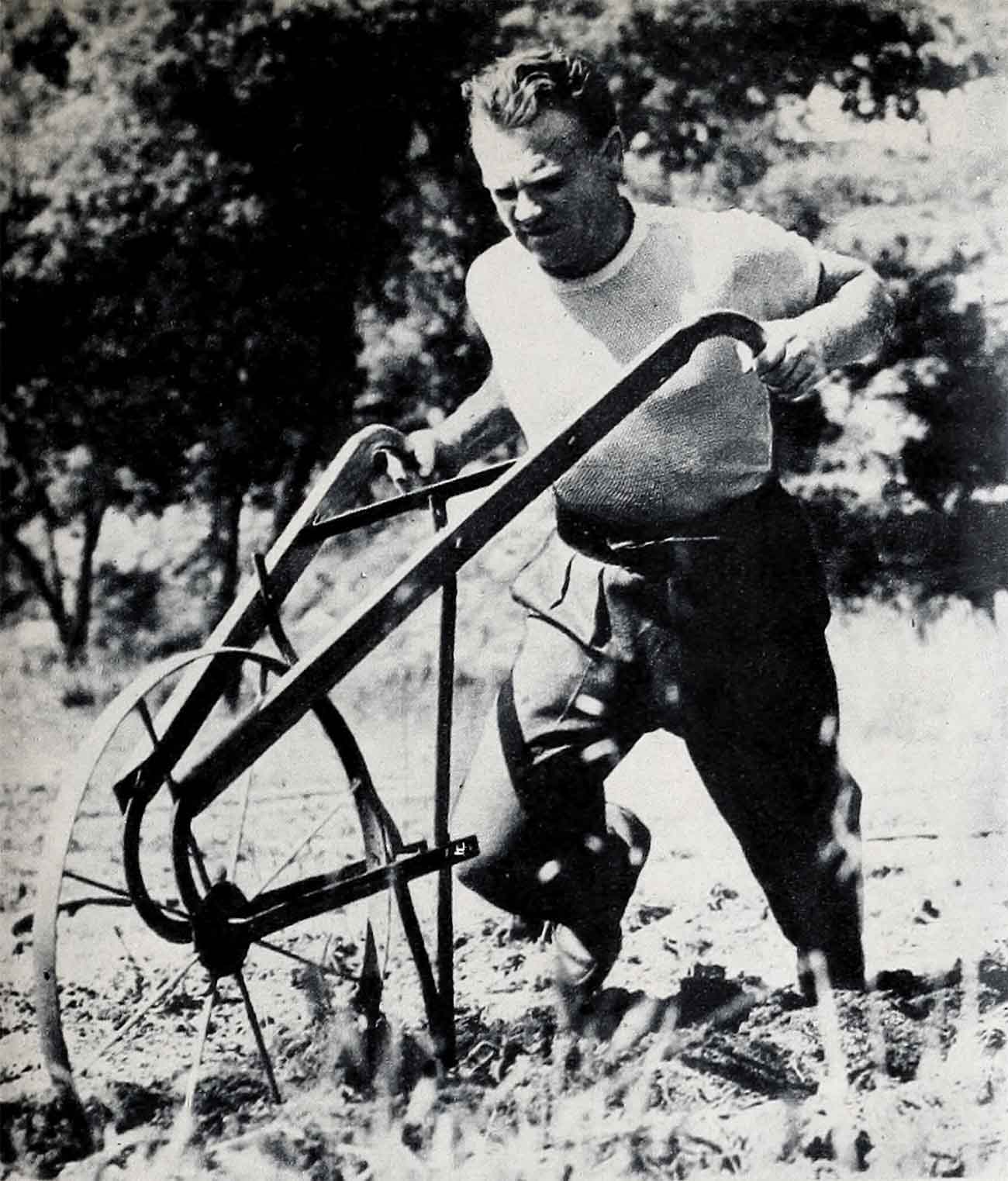

Not long ago, when “Blood On The Sun” was being shot, Cagney was needed un-expectedly for a retake. He was located in the grounds of his Hollywood estate, spreading on the lawn what farmers, year in, year out, find it expedient to spread.

“Do you have to have me now?” he asked plaintively. “I can’t get anyone else to do this job and it’s got to be done.”

“I can’t find any other Jim Cagney either,” the director said, so Cagney laid down his fork and drove pell-mell to where the cameras were waiting.

The discrepancy between the wages received by spreaders of fertilizer and Jimmy’s last salary, that ran up into the thousands per week, is enormous, but, to Cagney, any kind of work is dignified, with the possible exception of playing romantic love scenes. Jimmy balks at that. Some time ago, in “City For Conquest,” he did a tender episode with Ann Sheridan, and, if the fans are good judges, was tremendous in it. Nearly always, however, he ducks the cooing and the clinches, the murmuring and moonlight to which so many of the popular stars are addicted.

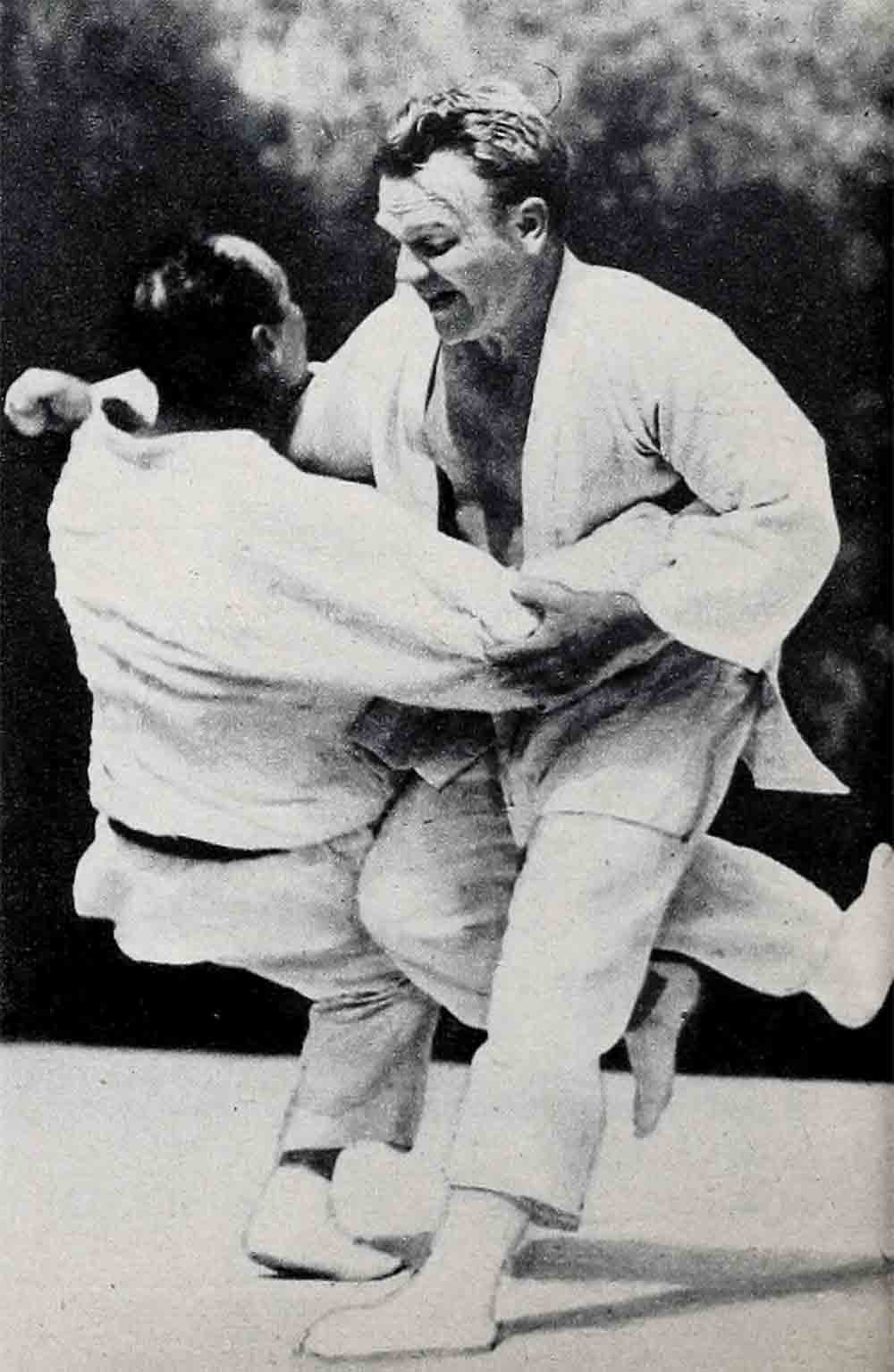

Cagney’s latest fad is a kind of Japanese wrestling or modified murder called judo. To be accurate, I should say his fads are judo and jiujitsu. There are subtle differences between these two types of mayhem, and Cagney is quite eloquent about them. He speaks of these nuances in the way a jazzman would point out distinguishing characteristics in a riff by the late Joe Oliver, as compared with one by Louis Armstrong.

“Blood On The Sun” contains a terrific fight between Jimmy, as editor of an American newspaper in Tokyo, and a terrible Jap. Conscientious, as always, Cagney hired a judo professor and also a jiujitsu expert. With what he has gleaned from the pair of them, he attacks his unlucky colleague and the result would make the fight in the “Sea Wolf” look like a game of patty-cake. Jimmy got to be so fond of judo and the other school of Japanese wrestling that he has continued his lessons long after the picture has been sealed in the can. For milder exercise, he keeps up his tap dancing, ploughs, shovels, plays baseball and shuns the pleasures of table and bar. Not excessively, however.

When asked which picture afforded him the most fun, while it was in the making, Cagney replies without hesitation: “The Strawberry Blonde.”

He still chuckles as he recalls the days when, with Rita Hayworth, Olivia de Havilland and Jack Carson, he romped and cavorted all over the lot. The cast had as much fun as the audience was later to have and that is saying a great deal.

Jimmy’s favorite singer is the tenor, McNamara, who was a cop on the New York force until discovered by Caruso. There is nothing Cagney would not pass up to hear him sing again, if that were possible, “The Old Orange Flute,” or “Fifteen Acres.” He dotes also on the records of Burl Ives, preferring him to other singers of American folk songs. He likes Josh White, too, and his “One Meat Ball.”

Looking toward the future, it is, candid to realize that Cagney will not always be fit and forty, but there are signs that the industry is growing up as fast as some of its good actors. The day will come soon when audiences will not be as much engrossed in the love affairs of immature young people and will appreciate better the portrayal of mature men and women and their problems. Luckily, Cagney has never been handicapped with the magazine cover type of beauty.

He has a merry, mobile and even impudent face and should be just as effective at fifty and sixty as he was at thirty and is at forty.

Whatever happens, he will take it on the chin if it is tragic, and enjoy life to the fullest whenever the circumstances permit.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1945