The Truth About Shelley Winters’s Husband

A few weeks ago a tall, dark and incredibly handsome foreigner stepped out on the stage at the small Circle Theatre in Hollywood. In accented English he announced that he would recite some Italian poems—in Italian.

For the next two hours, without book or notes, he delivered what is probably the most amazing poetic reading ever heard in Hollywood. He ranged back to Virgil, through Dante and into the Italian moderns. Few in his audience understood a word he said, but in all that time there wasn’t a whisper, rustle or cough. He held them spellbound with his magnetic personality, with the rich music of his voice, his dramatically changing inflections, his eloquent, graceful gestures. The performance was so sensational that it had to be repeated. Afterward, he was swamped with letters:

One came from a man who wrote, “You have suddenly brought back to me the whole aim and excuse for acting, which has been forgotten—to lift up and inspire. I have not had this spiritual feeling since I heard Caruso sing.”

Actually, there was nothing surprising about this amazing exhibit of talent—only the fact that Hollywood was surprised. The magnetic young man is a poet himself, the author of a collection, Tre Tempi di Poesia (Three Stages of Poetry). He is also a novelist whose book, Luca dei Numeri, won literary prizes in Italy. He is a student of the law, besides, and a professor at the Italian Academy of Dramatic Arts. He has acted in 93 Italian plays and 20 Italian movies, directed seven plays himself and written as many. He is a classical as well as popular actor, who has brilliantly performed the works of Shakespeare and the classic Greek dramatists in the capitals of Europe. He has played Aeschylus’ The Persians for 35,000 people in the ancient Greek theatre at Syracuse and also in Paris and London, where the crustiest British critic rhapsodized about him, “tonight a young god walked on the stage and illuminated the theatre with his brilliance.” He was the first actor allowed to portray Christ in Britain, where it was against the law.

Two years ago Ingrid Bergman answered the interested query of Sam Zimbalist, a Hollywood producer then in Rome, “Oh yes, he’s the finest actor in Europe today,” an opinion echoed by her husband, Roberto Rossellini.

Besides all this, he is a championship fencer, with three cups to prove it, and a former center on the Italian Olympic basketball team. He’s muscled like a boxer, which he has been, is as tall as a grenadier, which he has also been, and is so good-looking you could call him beautiful. On this September first he will be 30 years old. Obviously, he’s quite a guy.

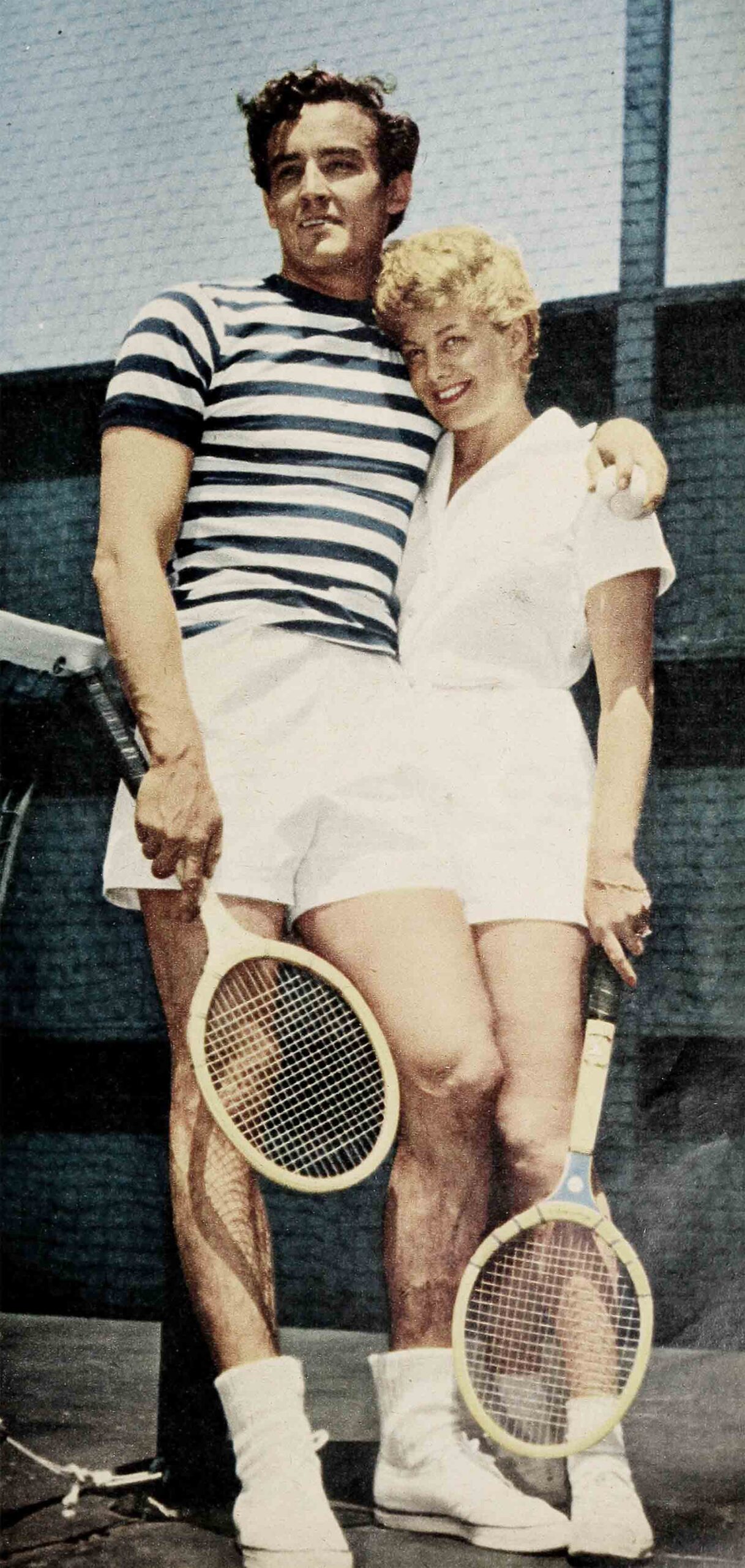

Yet until recently and indeed throughout the past year he has been known in Hollywood frivolously and usually disparagingly as merely “Shelley Winters’ Roman Romeo.” Now he’s her husband. His name, of course, is Vittorio Gassmann.

A town that makes millions playing fortissimo the theme of romance, just couldn’t believe the real article when it happened to a home town girl. Well—now the joke’s on Hollywood.

Not only did Shelley Winters find a true love match in Rome and become Mrs. Vittorio Gassmann in Juarez, Mexico, as of last April. 28, but what’s more she’s ecstatically happy, despite the sniping rumors you’ll hear from time to time. And Vittorio Gassmann, who never sought a job in American films until they sought him, experts now agree, may well become the greatest Continental star ever to grace Hollywood’s lots. Already his tense Displaced Person role in The Glass Wall, directed by Maxwell Shane and produced. by Ivan Tors, is introducing him brilliantly, and his romantic Mexican in Sombrero has MGM bosses pounding each other on the backs. He’ll star next as a convict in a highly dramatic film, Men Don’t Cry before he flies with Shelley back to Rome in October for what he considers his real life’s work, the classic Italian drama. He’ll be back in May.

But whether or not he becomes the greatest movie rave since Valentino, one thing is certain: Already Vittorio Gassmann qualifies as the most underestimated and misunderstood man in all of Hollywood’s cockeyed history. So maybe it’s high time to toss all the silly business out the window and level down on the truth about the amazing man Shelley Winters married. And that’s a pleasure . . .

Vittorio Gassmann is a true artist and you can tell that the minute you meet him. His head, from it’s thick wavy black hair to the prominent, pointed chin, is cleanly carved, and of noble proportions. His nose is aquiline. This Praxitelean perfection caused the cameraman on The Glass Wall to exult, “It’s a face that breaks into sculptured planes no matter how you shoot it. There hasn’t been a face like that around since Garbo.”

Vittorio’s eyes are dark brown pools that seem to reflect sadness one minute, excitement the next, tenderness and then gaiety, all in the space of minutes as you talk to him. His mouth is large, with sensitive, curving lips and a smile that flashes doubly white against his dark olive complexion. He has long, thin hands and he uses them expressively. His brow is high and wide, the brow of an intellectual. His speaking voice is low, rich and restrained. Yet with all this sensitivity Vittorio conveys an unmistakable impression of strength and masculinity.

Physically, he seems slight and thin, but actually he weighs 203 pounds, all bone and muscle. He stands six-feet-two, but walks gracefully like a cat. He inherited his physical strength from his father, Enrico Gassmann, a German engineer who came to Italy after the first World War and married Luisa Ambron, a Florentine girl who had always wanted to be an actress. Vittorio inherited his artistic gifts from his mother, and later she encouraged him to pursue them. He was born in Genoa, Christopher Columbus’ hometown, September 1, 1922. But when he was only five he was taken to Rome where he grew up.

Until he was 15 years old Vittorio Roberto (he never used his middle name) lived under the rugged domination of his father, a giant of a man, six-feet-five, who had duelling scars on his face and the brawny shoulders of a sculler. Vittorio was the only son, and his father was a rough trainer. When Vittorio was barely more than a baby, he tossed “Toto,” as they called him then, into the Mediterranean on one Riviera vacation, walked away and left him to sink or swim. Vittorio swam; he had to. He started him boxing and wrestling almost as soon as he could walk and turned him loose for the Roman kids, who raced around the ancient ruins, to complete the manly training. “Roman boys are rough,” Vittorio grins today. “They took over enthusiastically.” He has scars on his face today from street battles to prove it.

The Gassmanns weren’t wealthy. The highwater mark of family affluence, Vittorio remembers, was the purchase of an old Fiat car. But there wasn’t enough money to rent a garage, so it stood in the streets under the rains until mushrooms sprouted on the top. There was usually enough money, though, for entertainment. Only, while Vittorio’s mother and sister went to the opera and theatre, his father took him along to the soccer matches at the Stadio. He went to public schools—three years elementary, five gymnasium and three lyceo,where he quickly became a sports whiz and a top student. His artistic talents hadn’t a chance to sprout, however, until his father died, or rather, as Vittorio thinks, “killed himself.”

Not deliberately, of course. But Enrico Gassmann was a man who scoffed at illness and hated doctors. So when he developed acute appendicitis, he spurned medical care, took sweat baths and violent exercises to cure it. Peritonitis developed and he died. Vittorio was 15 then, and his mother took over.

She had rich material to mold because Vittorio was really a born artist and he secretly dreamed of being a writer. Up in his room he delved into the classical poets—Homer, Dante, and Virgil. Outwardly he kept up his athletics.

When he was 19, his mother took positive action. Unknown to Vittorio, she secured a borsa di studio(scholarship) to the Academy of Dramatic Arts and enrolled him. He had never acted in his life or even considered it. But when, back from a basketball jaunt, she told him the news, Vittorio remembers being pleasantly elated. “I was curious,” he says, “and I thought: An acting school—ah, there will be pretty girls!” Of course, all of this he sized up then as strictly a dilettante deal. Actors don’t get rich in Rome, seldom even the good ones. Most poets and writers starve, too. For his serious profession Vittorio was headed for the University of Rome and a course in law. In Italy it was not impossible to take on both schools at once, because universities there don’t hold classes. Facilities for study are available, and it’s up to you to pass periodic examinations on the way to a degree. Vittorio still has six exams to pass for his law degree. But he’s now on the faculty at the National Academy.

It wasn’t only the pretty signorinas who held his major intrest there—although Vittorio wasn’t disappointed in the scenery. But “little by little,” as he admits, “I turned into a—how is it—ham.” More accurately, what he found at the Academy was poetry in motion, a chance to be the poet that was inside him and the graceful athlete, too. In fact, his first fatal burst of applause came from a gymnastic feat in his first public play, Zorilla’s Don Juan. Vittorio played Don Luis and got skewered in a fencing duel with a sword atop some high stairs. “My fall to the floor was magnificent,” he smiles. “It—what you say—wowed them.”

After that he played in almost everything the Academy produced—musicals, operas, comedies, classic tragedies. He had one: more year to go on his three-year course when the Italian army called him for officer’s training with the Grenadiers, but that lasted barely two months because the Yanks were swarming up Italy’s boot and there wasn’t much future in being an Italian soldier. With the Allied Armistice, they let him go. Vittorio left the Academy, dropped his law courses and turned pro. To get a steady job he had to go into enemy country, up north to Milan, the Nazi half of Italy. He made his debut there at the Odeon Theatre, in a play called, appropriately enough, The Enemy.

It wasn’t exactly a climate you’d expect budding artists to flourish in. There were constant bombings and the imminence of Nazi concentration camps. But Italians are seasoned by a violent history, and they take life as it comes. The repertory theatre where Vittorio acted never closed, war or not, and he did 36 plays the first year. Salary—300 lira a night, or in American money, exactly one half-dollar. But in 1944, believe it or not, you could live pretty fancily on that in Milan. Vittorio lived in a good hotel and, as he modestly admits, “I was a big hit with the old ladies.”

The young ones liked him, too. Especially Eleanora Ricci, the daughter of Renzo Ricci, a famous Italian actor. They were married during Vittorio’s second year at Milan, when he was just 21. They have a daughter, Paola, now seven. But their marriage lasted barely three years. “We just didn’t get along,” is all Vittorio will say about that. There’s a point, in passing, however, which Hollywood ignored in its first uninformed gossip about Shelley and Vittorio: She was breaking up no home when she fell in love with the handsome Roman. Vittorio and Eleanora had been separated five long years before Shelley and Gassmann met, although, with no pressing reason for a divorce, he didn’t get his until ten minutes before he and Shelley said “I do.”

During those years Vittorio Gassmann became, as Ingrid Bergman truly stated, “the finest young actor in Europe.” Back in Rome after the war, he plunged into classical drama. He played everything—even American stage hits like A Street Car Named Desire, All My Sons, and Anna Christie. All in all, close to 100 plays lie behind Vittorio Gassmann, and in the best Rome theatres. He had his own company with the Italian actress, Maltagliata, for which he directed and wrote. In 1947 he published his prize-winning novel. He won top acting awards—more of those than money. So to support his family he made Italian movies—20 of them. The one with luscious Silvana Mangano, Bitter Rice, was the only one of the lot shown in Hollywood, where a girl named Shelley Winters saw it before she left for a European holiday. Pretty soon, in Rome, she was telling Vittorio Gassmann how much she liked his performance, which was the truth. And Vittorio was telling her how much he enjoyed her job in A Place In the Sun, which was a lie, he hadn’t even seen it. But, as Vittorio argues, “I had to have some kind of an approach, didn’t I?”

It’s a little late at this point to review the global romance of Vittorio Gassmann and Shelley Winters. Mostly, it can be summed up in Vittorio’s words. “Between us we supported the trans-Atlantic airlines.” Vittorio flew to Hollywood and home. Then Shelley flew to Rome for two months and they both flew back together to Hollywood. By then, of course, a certain understanding had been reached. In fact, it was after Vittorio flew home the. first time that Shelley sent him the gold key that is his most sentimental possession today. It carries the familiar French wish, “May we love as long as we live, and live as long as we love” and a more intimate inscription from Shelley: “Here is the key to my house and the key to my heart.”

There is one still lingering myth about those impulsive Hollywood flights of Vittorio’s, however, that needs to be punctured: He didn’t fly either time to get a job in Hollywood pictures. He flew to see Shelley.

Actually, Vittorio Gassmann had chances at Hollywood long before he met Shelley Winters. Three years ago Sam Jaffe, now his Hollywood agent, looked him up in Rome and shrewdly signed a managerial contract, even though at that time Vittorio didn’t speak English. Then Sam Zimbalist, fired by Ingrid Bergman’s report, told Mervyn LeRoy about him and suggested a test. But although Vittorio could have taken one all the long time that Mervyn directed Quo Vadis in Rome he never bothered.

It’s true, of course, that after Shelley Winters fell, curly head over high heels, for Vittorio in Rome he needed neither an agent nor press agent to sing his praises in Hollywood. Shelley told everyone she knew and a lot she didn’t in superlatives about Vittorio. Understandably, she had and still has the best reason in the world to want him here and now to keep him here. But Shelley faced a torturing dilemma one day not long before they were married.

She was at MGM then, making A Letter From The President. Vittorio had an appointment with Benjamin Thau, a top MGM executive about a proposed contract still in the talk stage. Shelley left him and flitted off to wardrobe, and when she returned she found Vittorio leaning dejectedly against a parked automobile, his face white as a sheet and looking to Shelley “as if he was about to cry.”

The cause of Vittorio Gassmann’s upset condition, incredibly enough, was something that would make the average actor new to Hollywood jump with joy. He had just been offered a seven-year contract at the greatest studio of them all, guaranteeing him more money than he could possibly make in Rome. But he hadn’t signed. Instead, he had walked out into the air to think, uncertain, torn and a little seared. He wanted to stay in Hollywood with Shelley. But seven years in this one place, making movies!

“Seven years passes quickly” Shelley argued. “I signed a seven-year contract not so long ago and already it’s halfway through. Before long you’ll be free to go back to Rome and financially independent for life.”

“Yes,” agreed Vittorio. “I know that. But there are so many things I want to do. Play Hamlet, act the classics, study, direct, write, travel. These are my young years, the years that count.

By now a lot of people, including Shelley Winters, understand a lot more about the intense, studious young Roman who has come, seen and started to conquer Hollywood. Mainly, they realize that the problem isn’t keeping Vittorio busy, it’s keeping him here. Frankly, Hollywood doesn’t particularly enchant him—for artistic, patriotic and practical reasons. Vittorio makes less but keeps about as much making pictures in Rome, where already he’s top man; there are lower taxes, no agents’ fees, cheaper living. Besides, being a Roman, anything away from his “terribly exciting city” Vittorio really considers camping out. He likes Hollywood all right, but he’s not impressed. “It’s exactly as it’s supposed to be,” he’ll tell you. “The architecture is a little—uh—mixed. But Hollywood is honest. It doesn’t pretend to be anything it is not” New York—that’s another thing. To his European eyes it’s ugly, rushing, noisy, nervous. Rome’s strongest pull for Vittorio is the classical drama. By now, of course, he has that compromise six months in Rome, six in Hollywood contract at MGM, which proved the answer to his riddle.

Already in Hollywood Vittorio Gassmann is respected as a flawless screen actor. He spoiled exactly one take during his entire first Hollywood picture. He impressed his hard-cooked crew, to whom no actor is a hero, much less a foreign one, with his talent, friendliness, and his moxie, too. They often broke into applause after his. emotional scenes and had to hand it to him for plenty of guts right from the beginning.

The first day of shooting after a late night, Vittorio had to race time and again up a long ramp at the United Nations Building. He disappeared after the first two tries, but came right back and carried on. Not until the day was over did they find out he’d ducked under the ramp and lost his breakfast. Another time some sailors aboard a boat, chasing Vittorio to an easy leap off a five-foot rail, got their timing confused and dashed to the action spot seconds late. Without hesitating, Vittorio climbed to the deck above and jumped down a jarring 15 feet so the scene would come out right. “Hey,” protested his director admiringly but concerned, “If you’re going to do stunts, I’ll hire a double.”

Gassmann laughed. “In Italy,” he said, “an actor who has a double is a sissy.” Last day of the picture his crew tossed Vittorio a dinner and strung a banner across the studio street. “YOU’RE A GREAT GUY, VITTORIO,” it read; “WELCOME TO AMERICA. WE WANT YOU TO STAY.”

Actually, Vittorio Gassmann has had no trouble at all adjusting to America and Hollywood. Basically, he is a sophisticate who stays himself and indulges his tastes no matter where he is. The glamor of movieland doesn’t intrigue him; on the other hand it doesn’t bother him. He lives with Shelley in her small Hollywood apartment with no plans for anything more pretentious until they come back from Rome.

Each morning he rises early and reads the classics, an hour before Shelley gets up. Sometimes he writes, sometimes he just sits and meditates. To Shelley her husband is a mathematical man—the most disciplined, organized person in the world. “Why,” she’ll tell you, “I twirl around like a dervish but nothing happens. Vittorio doesn’t make a wasted motion and everything’s buzzing along all the time!”

Little of the buzzing is frivolous. Vittorio’s no stuffed shirt, though. He likes to go dancing, for instance, at Ciro’s and Mocambo now and then and does, although “fun” to him usually means a play, Opera or concert. “I do a very good samba” he’ll inform you with no false modesty, explaining that he learned it in Brazil where he took an Italian company on tour last year. He doesn’t care for big parties, but agrees that they’re the same all over, usually a bore but sometimes amusing. Food to him is important and so far, while Shelley struggles with cookbooks from scratch, they’ve been practically living at Hollywood’s Italian restaurants like the Naples, because Vittorio’s not tactful about American fodder at all. To his palate, it’s awful. “Everything,” he thinks, “has peanut butter on it or mayonnaise.

But there is nothing superior or condescending about Vittorio’s manner; on the contrary, he is as friendly as a pup and sometimes seems actually naive. For most of his pet American peeves, he has discovered something else he likes. If he does abhor television, hurried meals, and traffic signals, he’s crazy about Hollywood’s casual clothes, his second-hand Chevvy, and of all things, fresh milk.

For cosmopolitan Vittorio Gassmann the shuttle between Rome and Hollywood should present no major problems. A new language, for instance, to a man who already spoke five, has already proved a breeze. The first sentence Vittorio spoke to Shelley, barely a year ago, was halting and incomplete. “You—very—fine—artist, I theenk.” But by now he can talk and understand American as well as anyone, even slang, and his accent irons out more every day. Shelley taught him. So now, with the new intercontinental life in view, Vittorio’s returning the compliment—with the aid of a steadily spinning linguaphone and daily lessons with a professional Italian language teacher.

But I wouldn’t say that Shelley Winters is considering rivaling her Roman mate at the drama on his own home grounds or anything like that. Not at least if the lesson I saw scribbled on a scratch pad the other evening when I dropped by the Gassmanns’ is any indication of her thoughts. It read in Shelley’s fine hand:

“Buona sera, Caro (Good evening, Dear)

“Hai lavorato molto? (Did you work very hard?)

“Hai fame? (Are you hungry?)

“Cena e pronta (Dinner is ready)”

That’s nothing out of Dante, of course. But with a lesser Italian poet named Vittorio Gassmann, who came to Hollywood with a couple of strikes against him, it makes a hit—just as Vittorio has with Shelley Winters and everyone else who’s been lucky enough to meet him.

THE END

—BY KIRTLEY BASKETTE

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1952