Beverly Wills: “I Almost Married James Dean”

I was Jimmy Dean’s girl friend. We went steady for seven months, and at one time we talked about getting married. I loved Jimmy at that time and I understood him as few people did.

We met on a blind date about five years ago. He was a bashful boy behind big horn-rimmed glasses and his hair looked as though it hadn’t been combed in weeks. When we were introduced he merely said, “Hi,” and stared at the floor.

Finally we got into his car and drove to a shore picnic—and he hardly said a word. He was a little self-conscious about his car, not because it was beat-up looking, but because he couldn’t whip any speed out of it. “Good old Elsie,” he said with a wry kind of smile, stroking the wheel. “I call her Elsie because she’s slow as a cow. I hate anything slow. I wish I could trade this in for a fast job.” After that little speech, he clammed up and didn’t say another word.

I thought he was pretty much of a creep until we got to the picnic, and then all of a sudden he came to life. We began to talk about acting and Jimmy lit up. He told me how interested he was in the Stanislavsky method, where you not only act out people, but things too.

“Look,” said Jimmy, “I’m a palm tree in a storm.” He held his arms out and waved wildly. To feel more free, he impatiently tossed off his cheap, tight blue jacket. He looked better as soon as he did, because you could see his broad shoulders and powerful build. Then he got wilder and pretended he was a monkey. He climbed a big tree and swung from a high branch. Dropping from the branch he landed on his hands like a little kid who was suddenly turned loose. He even laughed like a little boy, chuckling uproariously at every little thing. Once in the spotlight, he ate it up and had us all in stitches all afternoon. The ‘creep’ turned into the hit of the picnic.

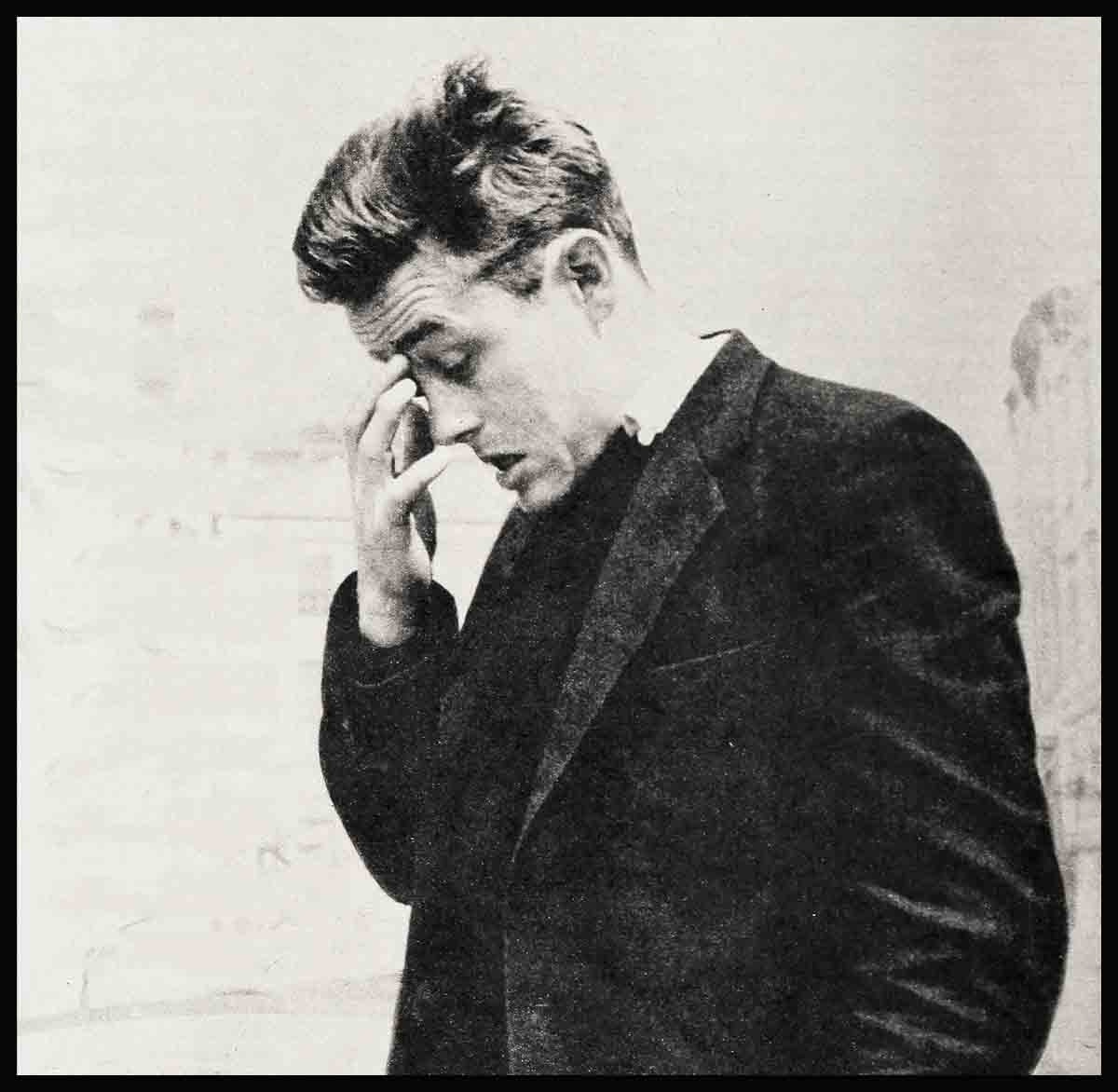

I learned that it was nothing for Jimmy to run through a whole alphabet of emotions in one evening, alternating sharply from low to high and back again, and no one could ever tell what mood would hit him. A couple of nights later, we went to a movie and during the picture Jimmy sat hunched forward, his chin cupped in his hands, looking something like that statue of the thinker. When I tried to whisper something to him, he shushed me up. He was so completely absorbed in the performance on the screen! Jimmy was still in this somber mood when we left, and when we got into his car he didn’t say a word. Suddenly he said, “I feel like some music.” He started to sing “Roll, Roll, Roll Your Boat.”

I was beginning to see Jimmy every day now and I noticed that he always wore the same clothes, a blue jacket and gray slacks. Either that or a pair of jeans. That was all he owned.

Once he spilled coffee on himself and it left a stain on the slacks. He jumped up and was so mad at himself. I couldn’t understand it, because Jimmy didn’t seem to give a hoot about clothes.

“It’s only a pair of pants,” I said, “send it to the cleaners.”

“That’s just it,” he said. “I can’t even pay the cleaners, and I wanted to go to the studio tomorrow and see about a job.”

Jimmy wanted more than anything else in the world to become an actor. But he couldn’t get a job. It would almost kill him when he’d go out to see the casting directors and return with nothing. He never lost confidence in himself, but he was angry because no one else shared that confidence. He would come by and see me after a fruitless interview, and he’d be in a black mood. “The director said I was too short,” he once mumbled savagely. “How can you measure acting in inches? They’re crazy!”

They also told him he wasn’t good-looking enough, and always that he wasn’t the type. Usually, when the casting heads told him this, Jimmy would get so mad he’d insult the men right back!

A charmer as well

I was doing a part in the radio version of Junior Miss, and Jimmy would sit in on the rehearsals and watch. One day, they needed a young man for one of the roles and Hank Garson, the director, asked me if my boy friend could handle it. “Of course,” I said happily.

I introduced Jimmy to Mr. Garson. “Have you ever done anything in radio?” asked the director. Any other actor, faced with such an opportunity, would have said yes, but not Jimmy. I think he was a little angry at the director for having let him sit around for so many weeks before offering him a job, and he wanted to show off. Anyway, Jimmy looked defiantly at Mr. Garson and said, “No.” “Sorry,” said the director, and walked away.

I ran after Jimmy. “Why did you say that?” I asked. “Why didn’t you tell him you could do it? If you’d only been nice he’d have given you a chance.”

Jimmy was still stubborn. “I don’t have to lie to get a job in radio. Either he can give me a chance because he thinks I can act, or he can take his old job.”

But although he used to rub many people—unfortunately, important people—the wrong way because of his hurts and resentment, he could charm the birds off the trees when he wanted to.

My mother didn’t share my enthusiasm for Jimmy, nor was my mother to blame. Jimmy had the knack of putting his worst foot forward when he was in the mood.

Morose and moody

I think it was the rebel in him. My mother—she’s Joan Davis—was a success; he wasn’t. Inside, Jimmy felt a little antagonistic toward many of the people who had achieved success in a profession where he couldn’t stick his foot in the door.

He’d walk into our living room and promptly slump down in my mother’s favorite arm chair, his foot dangling over the side, and sit like that for hours without saying a word. The only action we’d see out of him was when he’d reach out for the fruit bowl and eat one piece of fruit after another until the bowl was empty. When my mother would walk in, Jimmy never stood up, never said hello. He just remained slouched in the chair, munching on the fruit and staring moodily into space.

At the dinner table, his behavior was usually the same. Jimmy was always hungry. He loved pot roast, so I tried to have it for him whenever he was over. He’d wolf down two helpings of the meat with that same morose expression on his face, and mother would squirm.

It was more than his manners that disturbed my mother. She was afraid we were becoming serious. By this time I was wearing Jimmy’s gold football on a chain around my neck. We were going steady and my mother couldn’t think of any boy who had a more uncertain future than Jimmy! She thought he was too wild and would never settle down.

“Mom was flabbergasted”

My high school senior prom was coming up and, of course, I was going to take Jimmy. He was working as an usher at the time, and although he was in debt, he managed to put aside a few dollars every week so that he could rent a tuxedo. He asked me to go with him to the place where you rent these things, and when he saw all the dinner suits on racks he acted like a little boy in a candy store. He tried on one after another, and finally settled on a white jacket, black pants, dress shirt and bow tie. The rental on the whole works amounted to five dollars, and I don’t think I ever saw Jimmy look happier.

“Imagine me in one of these things,” he crowed, posing in front of a long mirror.

Although we sat out most of the dances—Jimmy didn’t rhumba or jitterbug—he was in wonderful spirits the night of the prom. Some of the kids at school joined us and he laughed a lot and told funny stories. My mother stopped by with some friends for a few minutes, and even she was fascinated by Jimmy’s personality that night. He jumped out of his chair when she came to our table and even helped her off with her stole. “Good heavens, I’ve never seen him like this before,” said mother, flabbergasted but charmed.

The only other times I saw Jimmy that happy was when he was racing his motorcycle furiously. No matter how depressed he was, if Jimmy had a chance to get behind something that had terrific speed, he would laugh and come alive again.

When Jimmy learned that I had a little boat with an outboard motor, he was eager to try it out. Jimmy drove it around the cove, the salt spray making his face and his glasses glisten. I thought he enjoyed it, but he was disappointed because he couldn’t get my little boat with its ten horsepower motor to whip up any great amount of speed. After that little ride, which I thought would turn out to be such fun, Jimmy was in the dumps again.

We wanted to get married

I soon discovered that his moods of happiness were now far outweighed by his moods of deep despair. He was almost constantly in a blue funk. He still couldn’t get an acting job and he was growing increasingly bitter. I hated to see Jimmy become so blue. When he was happy, there was no one more lovable. When he was depressed, he wanted to die.

These low moods became so violent that he began to tell me that he was having strange nightmares in which he dreamed he was dying. The nightmares began to give him a certain phobia about death.

“If only I could accomplish something before I die,” he once said despairingly. Like a lot of kids who go steady, we be man to talk about getting married. I was lot yet eighteen and we both knew my parents would never give their consent, so we planned to wait until my eighteenth birthday, which was a couple of months off, and elope. I had saved some money from my radio work, and we thought we would go to New York where we hoped Jimmy could get a break in the theatre.

But the dream didn’t last long. A couple of months later, I had moved to Paradise Cove, a beautiful spot way out at the each, where I was to spend six months with my father—my parents are divorced. The first week Jimmy drove out the long istance he began to gripe. “It’s such a long drive, I’m running out of gasoline. Why can’t you meet me in Hollywood?”

But I felt at home at the beach. I was with a lot of happy kids whom I’d grown up with every summer, and we were having lots of fun. Somehow, in this happy-to-lucky atmosphere, surrounded by boys and girls who didn’t seem to have a care in the world, Jimmy stuck out like a sore thumb. He wore the same blue jacket and tray pants, only they seemed even next to the tailored slacks and sports shirts the other fellows wore. The whole crowd was very cliquey, and when Jimmy came by they looked at him as though didn’t belong.

Weeper into the shell

Jimmy was very sensitive and it hurt him very much to be looked down on. He sensed their patronizing attitude and withdrew deeper and deeper into a shell. I think he wanted to hurt them back, too. I’ve often wondered if he recalled this period in his life when he portrayed the sensitive feelings of the rejected youth in Rebel Without A Cause.

One afternoon, the fellows were playing football on the beach. Jimmy joined them. Jimmy used to be very intense about everything he did, particularly if he wanted to show off. The other fellows were playing casually, since they weren’t wearing protective football gear, but Jimmy plunged into the game like a tiger. He was out for blood. He was very strong, anyway, and he tackled one of the fellows with such ferocity that the boy yelled out in pain and the rest of the fellows ran over to pull Jimmy off him. After that, the fellows labelled Jimmy a bum sport and wouldn’t talk to him.

Jimmy was miserable. He felt like an outsider in his work; he felt like an outsider with this crowd. The resentment made him sink all the more into rebellious moods that even I couldn’t understand.

At a dance at the Cove one night, Jimmy remained in this strange mood. When one of the boys cut in and tried to dance off with me, Jimmy saw red. He grabbed the fellow by the collar and threatened to blacken both his eyes. I should have realized that this was his way of paying back a member of the crowd who had hurt him. But I was embarrassed. I ran out to the beach, and Jimmy walked after me, scuffing angrily at the sand, complete misery on his face. We had an argument and I pulled his gold football off the chain.

An air of bravado

A few days later, Jimmy called and told me that a friend was driving to New York and would give him a free ride. I was glad he called. I had been thinking of Jimmy ever since we broke off, and I realized more and more that this was a hurt and misunderstood boy. I wanted to remain his friend. I wished him luck.

A few months later my mother took me on a trip to New York. I had Jimmy’s address. He was staying at the Y and I called him up. We met in Central Park and my heart went out when I saw Jimmy walk up in the same blue jacket and gray slacks. That meant that he still hadn’t gotten a job.

There was an air of bravado about Jimmy which soon crumpled when he told me that he hadn’t been able to land a part in a show. He was depressed, and he was hungry, too. I insisted that I buy us both a spaghetti dinner and he took me up on it. I think it was the first square meal he had had since he left Hollywood to come to New York.

I told him I was engaged to be married, and he told me about a girl he had met in New York who was a lady bullfighter. I could see that he was fascinated by this colorful girl. He showed me a tiny matador sword which he wore in his lapel, and he had gone overboard on the subject of bullfighting.

Later, he walked me back to my hotel. Just before he left he said, “I’m trying out for a part in a play tomorrow. It’s a good, gutsy part. If I get it, I think this will be the break I’ve been waiting for. Maybe even Hollywood will sit up and take notice. I’ll show them. If I don’t get it,” he paused, fingered the little sword in his lapel, and the familiar little smile played over his lips, “well, then I’ll go to Mexico and become a bullfighter.”

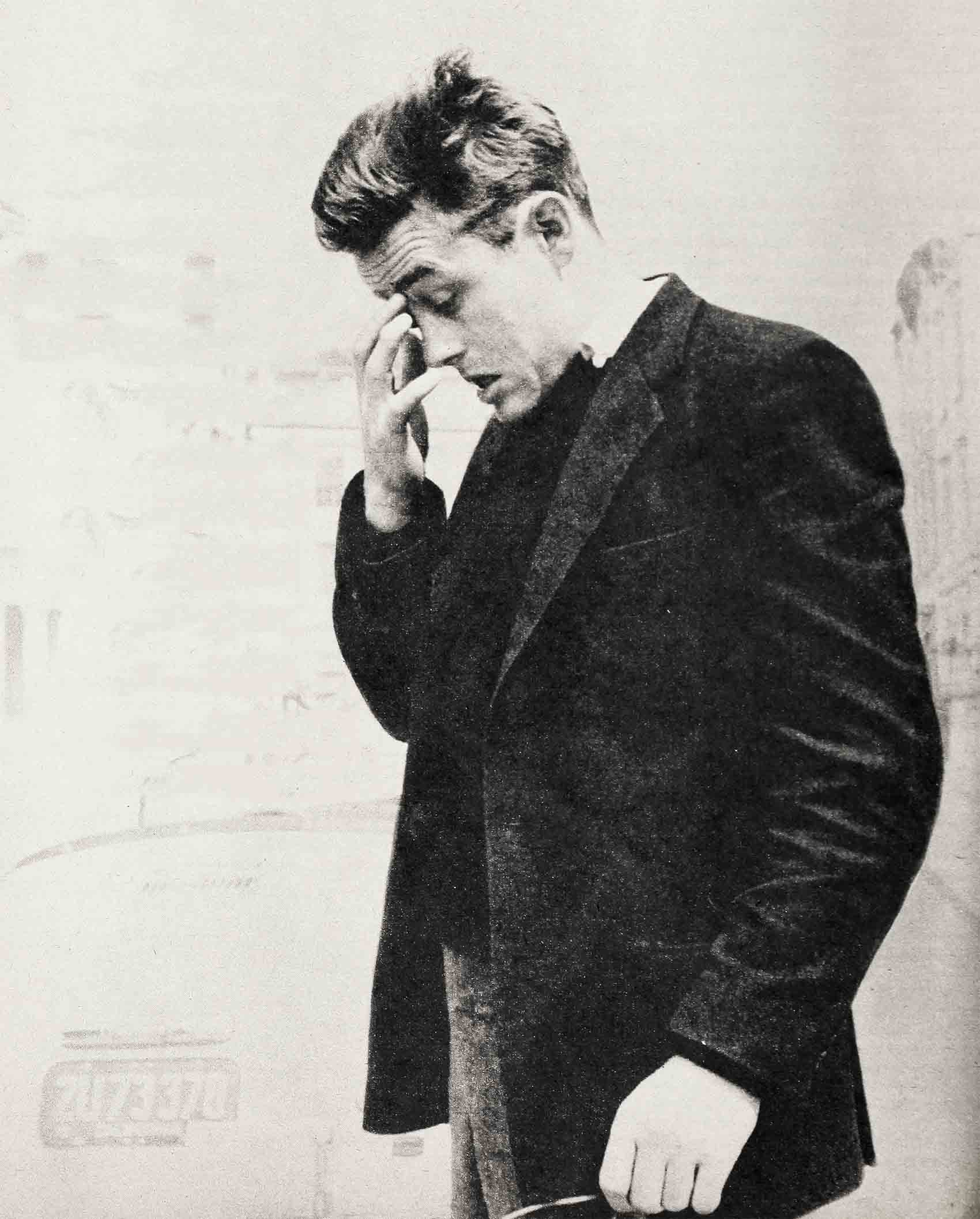

I kissed him on the cheek and wished him well, and then watched him walk down the street. He kicked at some stones like a little boy scuffing down the street, and he stopped under a lamp-post to light a cigarette.

Then he squared his shoulders, turned the corner and was gone.

He never did go to Mexico.

THE END

—BY BEVERLY WILLS AS TOLD TO HELEN WELLER

Jimmy Dean can currently be seen in George Stevens’ production of Giant, a Warner Bros. release.

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE MARCH 1957