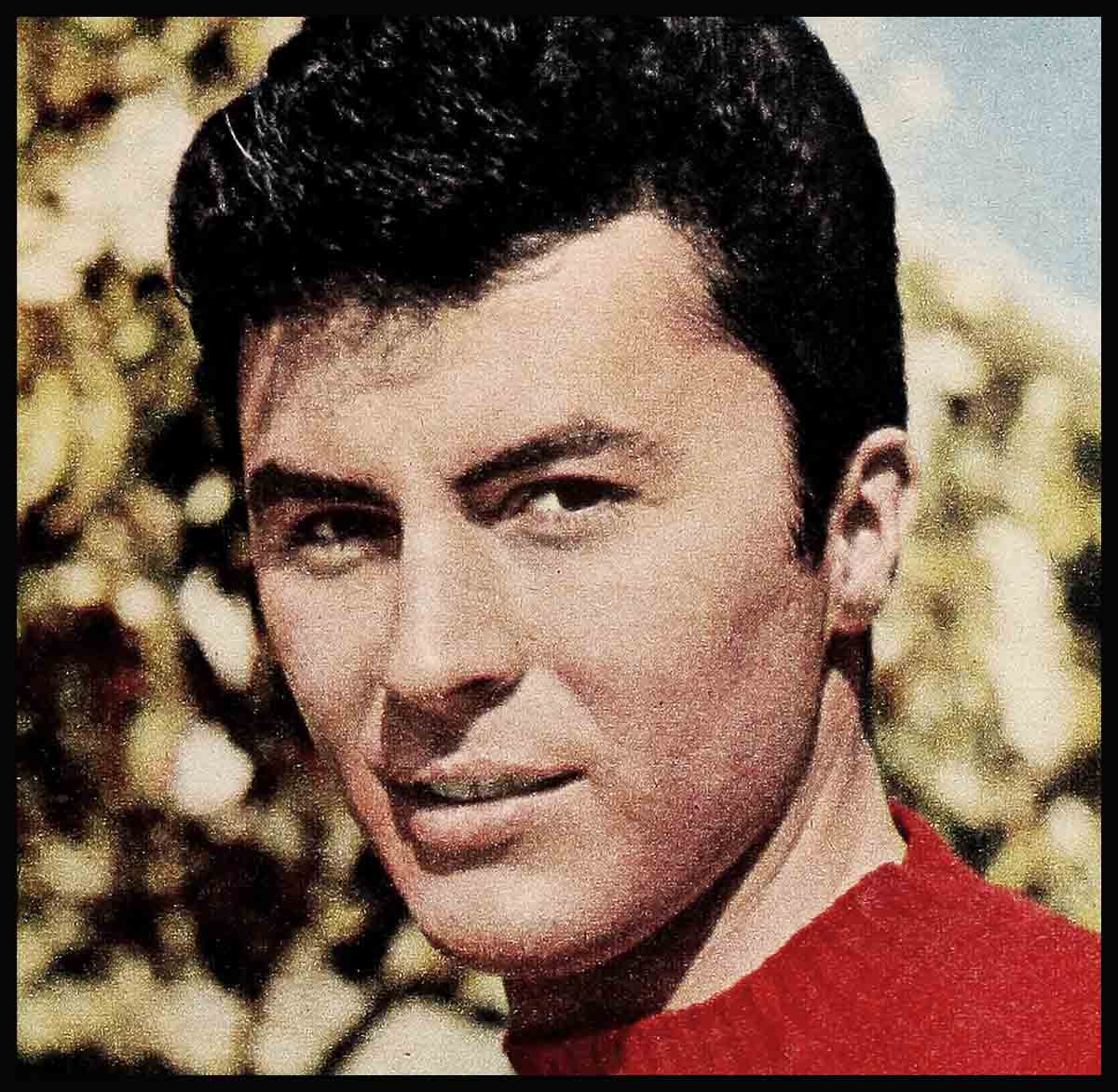

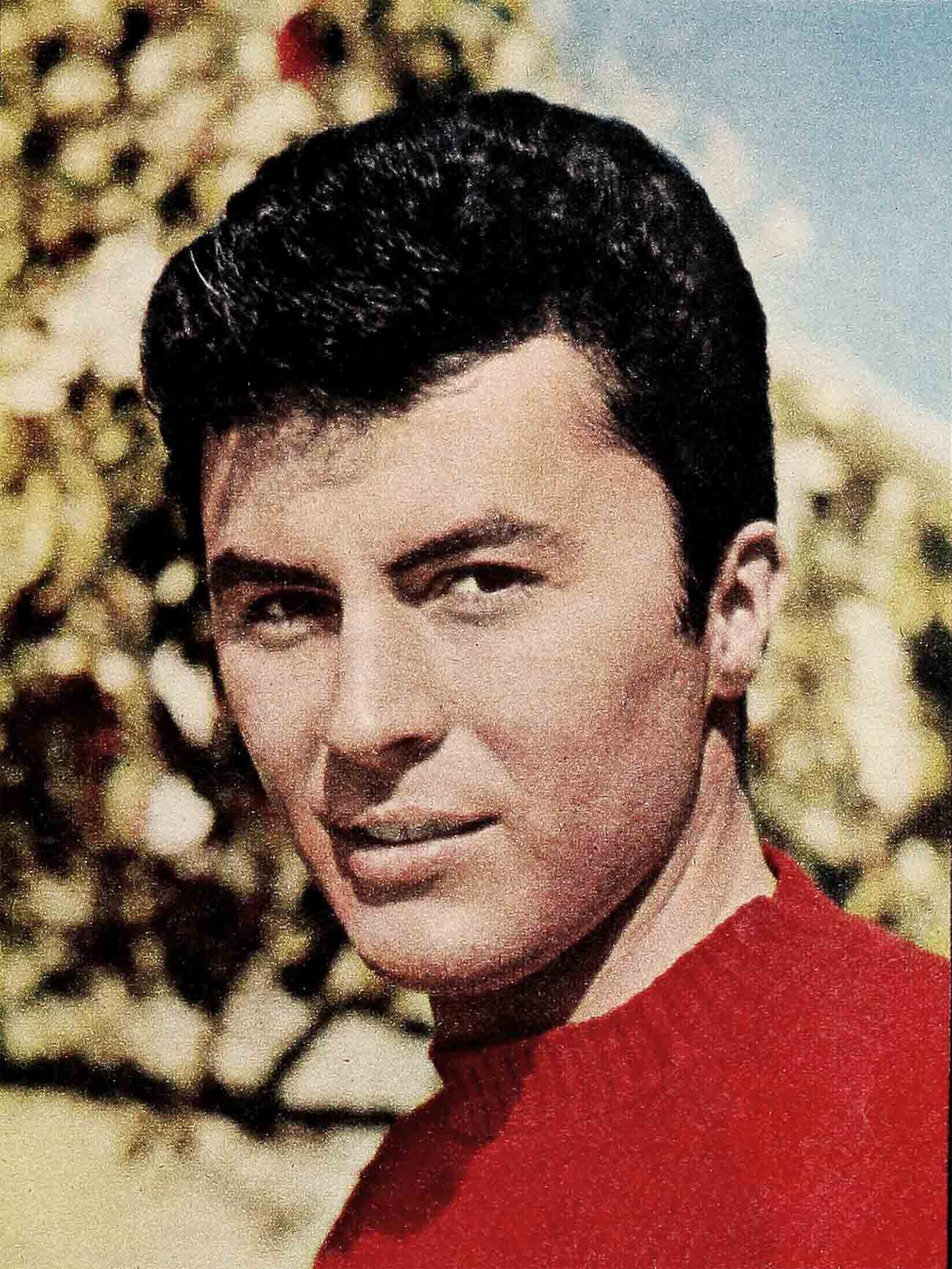

Life Story Of Hollywood’s Most Sensational New Star—James Darren

PART I

It was cold, freezing cold, that Monday night in Philadelphia as Jim Ercolani reached for his key and opened the door to his parents’ small apartment. It was nearly midnight and Jim thought the folks might still be up, watching television or something. But when he opened the door, he saw that the apartment was dark and he knew they were in bed already and he figured it was best this way. Because when he told them the two things he had to tell them this night they would be groggy and, he thought, sometimes it helps for your parents to be groggy when you’ve got to tell them things.

He walked through the living room, past his own room and into the folks’ bedroom. He stood there for a moment, staring at the dim outline of a saint’s picture his mother always kept on her dresser, praying quickly that the second bit of news he had to tell them would make them as happy as the first. Then he snapped on a lamp, walked over to the bed and gently called their names until they were both awake.

“Mama . . . Pop,” he said. “I was up in New York today and I got signed up for the movies.”

His mother, who’d awakened with a start, smiled for a moment and then burst into tears.

His father, who wasn’t really awake at all at first, snapped up into a sitting position and grabbed his son’s hand. “E vero, Jimmy?” he asked.

Jim nodded. “It’s true, Pop,” he said. And then he gulped—because glad as he was that his folks were so glad, he was sorry they’d got over their grogginess already.

“And you don’t smile at this good news?” his father asked, still clutching at his nineteen-year-old son’s hand and grinning broadly.

“Well, Pop… Jim started to say, his voice dead serious.

Mrs. Ercolani turned suddenly. “Jimmy,” she said, “you didn’t do anything wrong to get into the movies, did you?”

“No, Mom,” Jim said.

“I mean,” Mrs. Ercolani said, thinking back to an incident Jim himself will tell about later in this story, ‘“‘you didn’t go locking up anybody in a closet or something?”

“No, Mom,” Jim said, and again he gulped. “It’s just,” he said, “that I wanted you to know I’m married.”

There was a long, but not very long, pause.

“To Gloria,” Mrs. Ercolani said, not asking.

Jim nodded.

“And it’s been about a year,” Mr. Ercolani said, not asking.

Jim nodded again—and his folks turned and nodded wisely at one another.

They’d suspected it, they told him now, but they were never really sure. And anyway, they said, it was wonderful news and why was Jim shaking so much all of a sudden; they knew that he’d always loved Gloria and now they loved Gloria too, and they wanted them both to always be very happy—and, Mr. Ercolani said, laughing and getting out of bed and reaching for his bathrobe, “What do you say, Mama, you make us all a nice cup of coffee and we celebrate our Jimmy being a movie star and a husband, all at once?”

The talk

From that point on, they sat and talked and laughed till the early hours of the next morning, reminiscing about the old days of Jim Ercolani, wondering about the new days of James Darren—the professional name he had decided on, thankful that all their years of dreaming and hard work were coming to such a wonderful end.

Mrs. Ercolani, being a mother—and a woman, wanted to know all about the wedding first. She had known Gloria, the pretty dark-haired Jewish girl from down the street, for about as long as Jim had, seven years. She knew they’d met when they were both twelve, that they’d started to go out together to things like the movies and the beach when they were about fifteen, and that for a couple of years now they’d been going out together every night of the week. But the wedding, Mrs. Ercolani wanted to know—what was it like and where did it take place and. . . .

“We only did it secretly,” Jim interrupted her, as if he had to explain, “because I didn’t want you, to feel you were losing a son so young.”

“I know,” Mrs. Ercolani said, “but how did it happen?”

Jim smiled. “Well,” he said, “for the last couple of years I’d wanted to marry Gloria. But always I told myself, ‘You’ve got to wait until you can support her.’ And then one day I realized it might be a long time and I couldn’t wait that long and so I asked Gloria if she’d marry me and she said yes. So a couple of nights later we got into a car and drove down to Elkton, Maryland. I needed a ‘father’ to give his consent and so we got this guy to come along and all the way down I had to teach him how to spell Ercolani so it would look right when he had to sign the papers. And then when we got there that part went all right, but I found out that all the weddings in Elkton were listed in a newspaper around there and I had to pay this reporter fifteen dollars to keep my wedding out of the papers.”

Mrs. Ercolani tsk-tsked. “You were too broke to get married right,” she said, “and then fifteen dollars—poof!

The bargain

“Well,” his mother said, winking, “tomorrow night you bring my new daughter-in-law over here for dinner and I’ll make a lasagna of fifteen pounds and that way well make everything even. Okay?”

“Okay,” Jim said, winking back.

Now it was Mr. Ercolani’s turn. How did his son get his movie contract?

Whereupon Jim told him the story, the true story, that even fairytale Hollywood finds it hard to believe.

“I went up to New York last Thursday to have some pictures taken,” he began, then told them how on his way out of the studio the photographer’s secretary, a warm-voiced middle-aged woman, asked him, “You’re interested in show business, aren’t you?”

“That’s right,” Jim had said.

“You got any leads?” the woman asked.

“No,” Jim said.

“Here,” the woman said, jotting down a name and address on a memo paper, “go over and talk to this lady.”

Jim thanked her and a little while later he was in the lobby of the Brill Building on Broadway, waiting for an elevator to take him up.

“When I got into the elevator,” Jim says, “this woman came in right after me. She began staring at me as soon as she stepped in and she stared all the way up. Then, when the elevator stopped at the ninth or tenth floor, she got out and I got out, too. She went into an office and I went to the receptionist’s desk. I showed the receptionist the note from the photographer’s secretary and she took me into an office. It was the same office the woman from the elevator had gone into. We both looked a little surprised to see one another. Then we shook hands and the woman asked me to sit down.”

The interview

“I like your looks,” the woman said, very matter-of-factly.

“Thank you,” Jim answered, running his hand across his face, as if to wipe away the sudden blush.

“Have you ever had any acting experience?” the woman asked.

“No,” Jim said.

“Any acting classes?”

“Well,” Jim said, “I signed up with a, school—Stella Adler’s—here in New York about a year ago, but I’ve only gone to about two weeks’ worth of classes.”

“Why?” the woman asked.

“Because I’m lazy,” Jim said.

“That’s an honest answer,” smiled the woman. “Now,” she said, “Tell me about yourself. What were you like as a kid, a young boy?”

“I was shy,” Jim said, starting slowly, “very shy, so shy that everybody thought I was conceited. If people said hello to me—I don’t know why—but I used to be embarrassed to say hello back and I’d just look down at my shoes and wouldn’t answer. Once in school, I remember, a girl said hello to me and I didn’t say hello back and later, when I saw her walking towards me with another girl, I heard her say, ‘Here comes that snob!’ It made me feel awful.”

“Were you a goody-goody then?” the woman asked.

Jim grinned. “No,” he said. “In other ways I used to be a pretty fresh kid.”

“Like when?” the woman asked.

“Like once in high school,” Jim said. “I was having a lot of trouble with this teacher and it came to the point where I couldn’t take it anymore and so I locked her up in a closet.”

“And?” the woman asked, trying to hide her smile.

Life on the farm

“And I got expelled,” Jim said, not smiling. “And then there was the time my kid brother, Johnny, and I were living on my uncle’s farm up in Woodstown, New Jersey, and there was this horse. Dixie was his name. He was blind in one eye. And when nobody was around we’d take him to the house and feed him. And then one day, just like that, he lay down and died. Johnny and I were with him at the time and we ran to tell my grandmother. We were crying and I remember my grandmother coming out to see Dixie and saying, ‘Si, é morto—yes, he is dead,’ and then taking off her apron and putting it around his head, sort of out of respect. Then we all just stood there and prayed that Dixie would be happy in whatever place he was going now.”

“Jim,” the woman asked, “have you ever done anything you’re real proud of?”

“That’s a hard question to answer,” Jim said.

“Have you ever done anything you’re really sorry about, then?” the woman asked.

Jim thought a moment. And then he nodded. “The trumpet,” he said. “I’d been studying trumpet for about three years and my father went out and bought me this new instrument, to kind of celebrate the anniversary, I guess. But I was really getting fed up with my lessons and I had this teacher who’d give me a poke in the arm when I played a wrong note sometimes. So one night I decided not to go for lessons anymore. I went to a candy store near the house instead. And when the teacher saw I didn’t show up, he phoned my father and asked him what was wrong. My father didn’t know, but he came-looking for me and he found me in the candy store hiding under a pin-ball machine. He really let me have it, right then and there. I tried to explain to him, that I was sorry about the new trumpet and everything, and I think it took him a while to understand.”

The kid in the night club

“Did you ever want to be a musician?” the woman asked.

“I wanted to be a singer,” Jim told her. “Ever since I was a kid, I guess that’s what I wanted to be. I remember when I was about nine years old singing for my grandmother all the time. Her favorite song was Besame Mucho and I’d sing it over and over for her. Then a few years later I told my father about my wanting to be a singer and he contacted a friend who knew a friend, and before I knew it I was singing at Frank Palumbo’s C-R Club in Philadelphia a few nights a week. Don’t get me wrong, Ma’am—this wasn’t for pay. It was just one of those deals where I’d be sitting at the bar—drinking glass after glass of hot water and lemon for my voice—and the floor show would begin and the MC would say, ‘We’ve got a special surprise for you tonight—a guest star in our audience named Jimmy Ercolani.’ I never could understand why he just wouldn’t say, ‘There’s a kid here tonight who’d like to sing for you people.’ Anyway, I’d get up to the bandstand and start to sing. I was always very nervous on my first number, but there’d always be some applause after it and so I figured if they want to sit and listen to me, I’ll be glad to oblige. After the first song, I’d get over my nervousness and the only thing that would get me then would be some of the musicians sitting behind me. There’d always be one who’d say to another, ‘Who’s he trying to sound like tonight—‘Frank Sinatra?’—or ‘Perry Como?’—or ‘Mel Torme?’ This really used to get me.”

“What did your parents think of your singing?” the woman asked Jim now.

“Oh, I never would allow my mother to come,” Jim said. “Everytime I sang anything in front of her she would start to cry, like it was the most beautiful voice and the most beautiful notes in the world. In fact, the only person I know who ever heard me sing professionally was my father, and that was because I was underage at the time and he had to come. What a guy he is, my father. He’s a tailor and all day he’d work hard in the store and then he’d go home for supper and then, instead of just sitting around and relaxing like other people, he’d come with me to the club and sit around for hours, till the early morning sometimes, just so I could get a chance to sing and practice.

“When I was a kid I never had many friends. Even now, I guess I don’t. But my father is probably the best friend I’ll ever have. He taught me a lot about electrical work, which he’s very good at, and when I got interested in making model airplanes he used to help me a lot. And I used to like to build cars, too—you know, take stuff out of the trash cans at garages and junk shops and put it all together and hope the jalopy would move when I was through—and even on this my father used to spend a lot of time helping me, because he knew that what I was doing was making me happy and so it made him happy, too.”

They like him

The woman smiled and then she reached for her phone. “I’d like to talk to Harry Romm at Columbia Pictures,” she told her secretary. A moment later, she was connected. “Hello, Harry,” she said, “there’s a boy here I’d like you to see.”

Within an hour, both she and Jim were seated in Mr. Romm’s office. They all talked back and forth for about fifteen minutes and then Mr. Romm got up, shook Jim’s hand and said, “You’ll be hearing from me.”

Jim heard the next day, by phone, in Philadelphia. Mr. Romm wanted him to come to his office on the following Monday for something “very important.”

Jim sweated out the week end in silence. Then, Monday morning at 11 o’clock, he showed up at the movie executive’s fancy office.

“I have a contract here for you to sign,” Mr. Romm told Jim. “And I’ll make a deal with you, We’re not going to bother giving you a screen test. And we never sign contracts till the party has read a scene first. But why don’t you sign this first, and then you can read.”

Nervously, Jim signed. And then, nervously, he read a scene from Golden Boy. And then, very nervously, he killed a couple of hours in New York before calling Gloria and telling her the great news and then going back to Philadelphia to tell his folks.

“A husband and an actor,” his mother said now, proudly, the tears still in her eyes, as they sat around the kitchen table—her, her husband and her son—drinking coffee and talking about what had happened.

“A husband and—I hope, an actor,” Jim said.

Then he looked down at his watch. It was late, and he started to bed.

“Don’t forget,” his mother called out, “tomorrow night—you and Gloria—the lasagna!”

“All right, Mom,” Jim called back.

A nice name

Then Mrs. Ercolani turned to her husband. “Papa,” she asked, “this name Darren that Jimmy says he picked for the movies. How did he think of that one?”

“You know how interested he’s always been in reading about sports cars all the time,” Mr. Ercolani said. “I guess it’s from the name of the English sports car.”

“Oh,” Mrs. Ercolani said. She repeated the name a few times. “That’s a nice name—James Darren—isn’t it, Papa?” she asked.

Her husband took her hand and squeezed it. “That’s a very nice name, Mama,” he said.

And after just a few months the name James Darren was to become a very nice name to the executives at Columbia Pictures in Hollywood, too.

Jim’s first picture after his arrival in the movie town was Rumble On the Docks. His part was small, but his impression on the fans was big and the mail started to pour in. In his next two pictures, The Brothers Rico and Operation Mad Ball, his parts were somewhat bigger and so was his impression on the fans and now the mail really started to come in droves.

Meanwhile, for the past year or so, the studio had had a hot script property on its hands. It was called Gunman’s Walk. Tab Hunter had been signed for one role; Van Heflin for another. But the third male lead was open, and had been open for a long time. It was an important role and the studio had to be sure it was filled right.

And then one day someone interrupted a casting conference and said, “How about Jimmy Darren?”

And that was it—the beginning of what everyone at Columbia bets will be the big-time for a young man who rates it.

Jim’s reaction to all this?

He’s still a shy-enough guy to say simply that it’s all wonderful and that he hopes he makes proud all the people who’ve helped him and had faith in him.

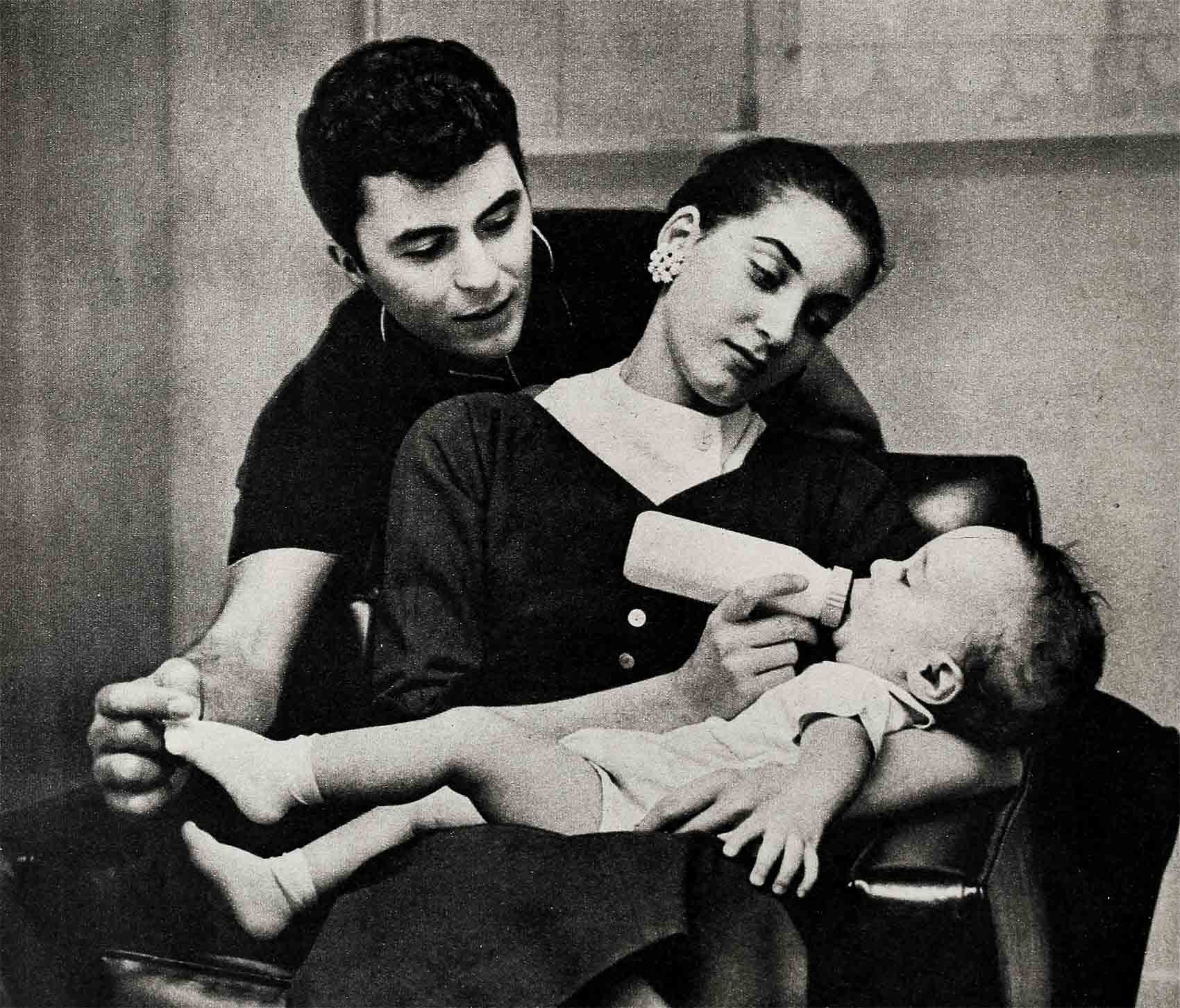

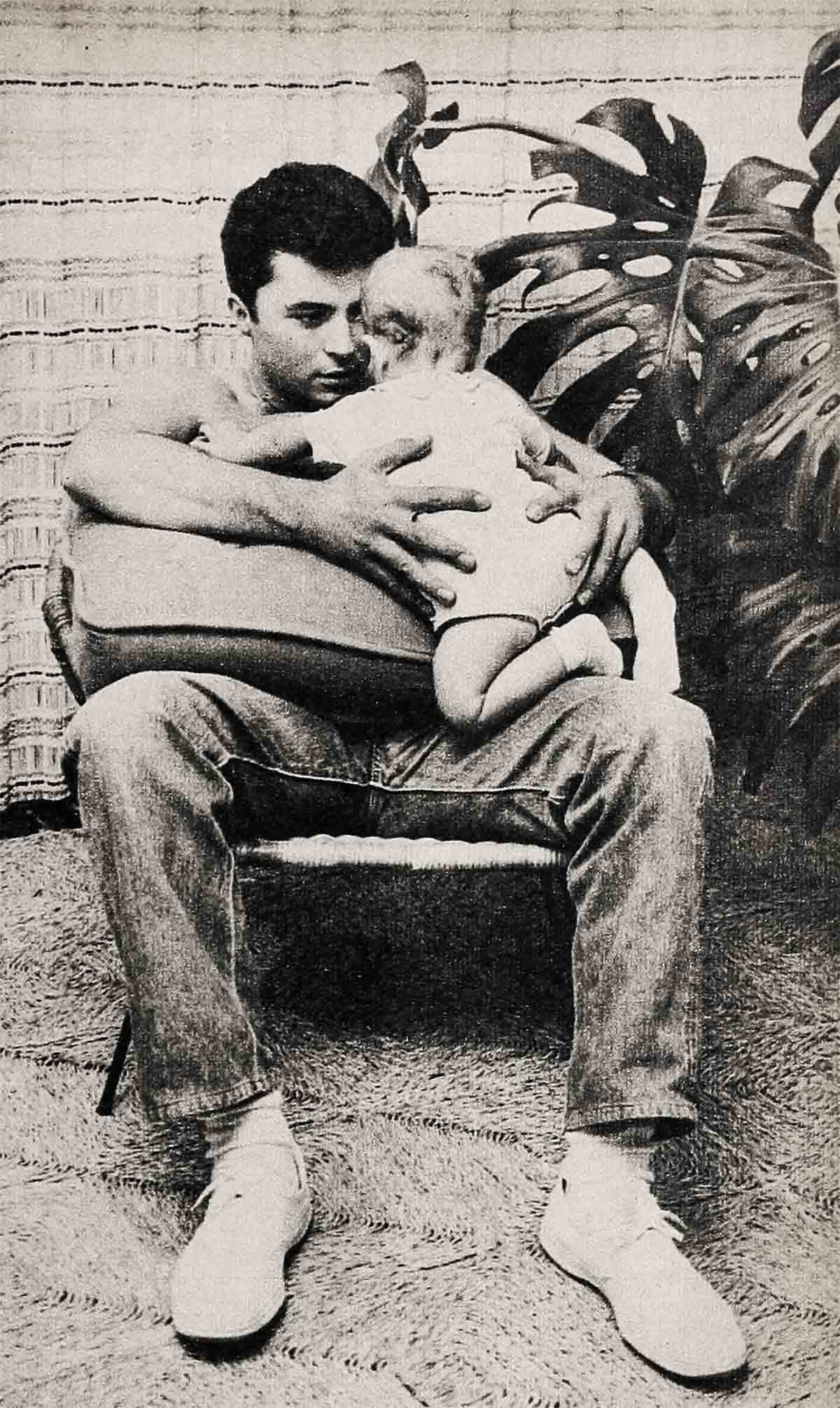

But talk to him just a little while longer and mention, in passing, that you’ve heard somewhere that he and his Gloria became parents not too long ago, and the shyness disappears like snow on a spring hillside and Jim sunnily tells you, “Yep, I’m a father. He’s a boy—name’s Jimmy. And let me tell you, it was the happiest moment in my life when he came. You see, when I’d thought about my having a child someday, I’d always hoped it would be a boy—so I could do things for him and build things for him and just be with him more than I figured I’d be with a girl. Of course, if it was a girl I would have loved her very much. But I really wanted a boy and—I couldn’t help it—but Gloria knew this, too. And I guess I really rubbed it in because one day before the baby came I promised her I’d bring two dozen roses to the hospital if she filled my order.

Da-Da (whistle) Da-Da

“I guess every parent thinks his child is unusual in so many ways,” Jim goes on, “but you want to hear about mine? Well, first of all, he can whistle already. He says Da-Da (whistle) Da-Da, with a real strong whistle in the middle. He calls everybody Da-Da, even his mother.

“And for another thing, he really loves music—especially Frank Sinatra. Every time he gets rambunctious all we have to do is put on a Sinatra record and as soon as the singing starts Jimmy quiets down and begins to wave his hand like he’s conducting. We call him Nelson Riddle sometimes. And let me tell you, it’s got to be a Sinatra record that will quiet him down. We’ve tried Jackie Gleason a few times—you know, that quiet sentimental music—but Jimmy just ignores it and keeps on being rambunctious until he gets what he wants.”

Then Jim smiles and says, “Gloria and I are with him all the time. That’s the way we’re happiest. We have a little apartment here in Hollywood and it’s just us and the baby and it’s great that way. We don’t go out much. I don’t like parties. I’d just rather not go to them. When Gloria and I want to get out we usually go to the movies, or else we get into my car and drive out to the Mojave Desert and I shoot. I don’t shoot at anything in particular; either just up in the air or at a few empty soda bottles I always keep in the back of the car. And sometimes, when we just feel like visiting with some other people, we go over and see Paul Piccerni and his family. Paul played one of my brothers in Rico. He’s got eight kids. I feel just like their uncle, we’re that close. In fact, one of the kids—Peevee, they call him—always calls me Uncle Charlie because the first time he saw me he thought I was Paul’s brother.

“Yes, it’s a great life,” Jim continues, “just the way we lead it. And it’s funny, but sometimes someone will ask me what’s your greatest wish. And I have to tell them that it’s that everything continues to go along just as nicely as it’s going today.”

And then Jim pauses and let’s you in on a little secret. “Although to tell you the truth,” he says, “deep down I wish to see the day when I’m enough of a success so that I can drive back home to Philadelphia in a shiny, new Mercedes-Benz, hand my father the key and say, ‘Here, Pop, this car is for you.’ And then to give my mother a check and tell her, ‘This is for a new house to live in after all the things you’ve done for me.’ This is something I really want to do someday. Then after that I can start thinking about my own nice car and house—for me, Gloria and the baby. If I’m worth anything out here, there should be plenty of time for all that to come true, you know?”

From where we sit, Jim, we’d say it should be a cinch.

THE END

You can see Jim in Columbia’s OPERATION MAD BALL and GUNMAN’S WALK.

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE MAY 1958