He Kissed Her . . . If Only He Hadn’t!—Stewart Granger

A seventeen-year-old girl named Jean Simmons wrote sadly in her diary of 1935: “Jimmy ruined a beautiful friendship today. He kissed me.”

The cad known as Jimmy was born James Stewart in London. Today under the name of Stewart Granger he exults in the fruits of his deadly osculation. Crime pays.

“I have the perfect wife,” says Deadly. “She can’t cook. She can’t make a bed. She will not pick up things. Dammit, she is perfect, and I wouldn’t change her.”

Asked if things didn’t get a little deep around the old Granger manse, he said, “I can cook. I can make beds. And I don’t mind picking up things—her things.”

Jimmy’s things presumably lie where they fall until help arrives.

“We have one maid who comes in every morning. She is perfect.”

Everything seems perfect in the Granger home. It’s a Byrd house. One of those cozy California nests named for architect Byrd. It perches on a mountain crest as close to heaven as you can get from Hollywood, fourteen hundred feet up as the jaguar flies.

There are two bedrooms, a living room that serves also for feasting and an electrified kitchen. All rooms open onto a terrace enfolding the swimming pool. In the morning Jean and Jimmy can dive from pool edge to Byrd bath. No one is around to see. Only the birds, the bees and the flowers, and they are too busy about their business to snoop on others.

Flowers scramble over an acre of garden.

“Are you a good gardener?” asked an old horticulturist.

“No, but I can tell a gardener how to be a good one,” Jimmy said.

Vegetables were Jimmy’s concern at the moment. Eating them, not growing them. We were lunching in the London studio of M-G-M, and everyone at the table was deeply involved in the potatoes and meat when Jimmy in lustrous coat of silver brocade with ruffles, the costume of “Beau Brummell,” cruised in from the set like a shining battle wagon. From his altitude of six feet three, he lowered his 190 pounds into a chair and called for a big bowl. Into this he subsequently pitched a stack of shredded cabbage, carrots, beets, parsnips, celery.

“I prefer fish and chips,” he said. (Chips are Mother Tongue for French fries.)

“I eat vegetables because they are fortifying and cleansing. Man was not made to be a carnivorous beast.” He threw a look at the carnivorous beasts around the table.

A trencherman hoisting a potato aboard was warned not to eat potatoes with meat. The potato fell. He reached for a roll.

“That’s bad,” said Jimmy. “Never combine starch and protein.”

Jimmy quoted doctors with strange names. I suspect they were all pseudonyms for old Doc Granger.

Medical advice stems naturally from Jimmy. He wanted to be a doctor, but after graduating from Epsom College, he hadn’t enough money for a medical course. He took a job with a London business firm. Age seventeen, with a diagnostic eye, he was able to tell the boss right away what was wrong with his business. The boss listened, then performed a major operation. He amputated Jimmy from the pay roll.

Still a firm exponent of free speech, Jimmy had the choice of speaking for free from a soapbox at Hyde Park corner or spouting from the stage at a salary of three pounds a week. He accepted the stage pittance which at that time amounted to fifteen dollars in American currency, enough for him to live at Mrs. Gallagher’s boarding house and dip heavily into her stew pot in which proteins, starches, vegetables all merged in memorable succulence.

A free thinker he has remained: “There is nothing I enjoy more than debunking everyone and everything—and especially me.”

In the early opulence of his film career he purchased the original cast of Rodin’s sculpture “The Thinker.” He set it up in his dressing room for emulation, no doubt, but it is hard to think of dynamic Jimmy in that static posture, chin on fist. His thoughts spray with the rat-tat of a tommy gun.

“I grill steaks for her on our barbecue range by the pool and I eat a few to keep her company,” he said. “Not more than three or four at a time. Never overload the stomach.”

With a sumptuous guffaw, he settled back in his chair ordered a cup of black coffee and mooched a cigarette.

“Nicotine poison,’ he said, inhaling cheerfully. “Speaking of poison, has anyone seen my picture?”

An ovation of silence ensued.

“I. saw Magnani in ‘Golden Coach’ last night,” peeped Paul Mills, publicity director.

“She’s great, isn’t she?” said a writer.

“Ha!” boomed Jimmy. “So Magnani is great. Am I great? Nobody knows. Nobody goes to see me. That’s the old M-G-M spirit. Publicity department boosts Italians. Mr. Goetz! Mr. Goetz!”

Mr. Goetz, the top brass, was deaf to the bellow. Probably a Magnani fan.

If you don’t know when Jimmy is serious, you are safer figuring never. Not always though. He can blow.

His wife, Jean the Perfect, is a trifle cloudy the first fifty seconds after waking; thence on, she is sunshine all the day. Temperate clime.

Her spouse, by contrast, is tropical. A blaze of sunshine for long stretches, interrupted by sudden clap of thunder, lightning and tornado that blows down sets and uproots men of oak. The squall subsides as quickly as it came up. Sunshine, rainbows, jokes and pats on the heads of kids after autographs, like the three who stood by the commissary door when Jimmy emerged jovially from lunch.

Admirers of Jimmy’s volatile performances in “Scaramouche,” “Zenda,” “King Solomon’s Mines,” “All the Brothers Were Valiant” or any of his twenty-four films are not disappointed in meeting up with him. He’s Granger plus. He’s Cinema-Scopic, as a live volcano.

Of all actors he is most gifted by temperament for the hot-headed, swashbuckling, dare-devil. He has the fire you expect in Latins which few have. Fencing and fisticuffs are old hobbies.

In “All the Brothers Were Valiant,” his fistic manslaughter made you feel the Four Great Powers had better consider Jimmy along with bombs—atomic and hydrogen. In the war, he was one of those kilted “Ladies From Hell,” heavyweight champion of his Black Watch regiment.

Nor is he content lambasting the frail carnivorous human species. In Africa while working in “King Solomon’s Mines” he took on five buffalo. The first buffalo stood Jimmy on his head and made him eat grass, most indigestible herb for a man. Thereupon Jimmy fed the buffalo hot lead, the hardest thing for a buffalo to digest. The other four buffalo died likewise of indigestion. Two rhinos crumpled with cramps.

No known mammal of Africa or Hollywood can stand Mister Granger on his head for long. He need not whack actors to steal a show. All he has to do is boom. His voice has the trumpeting power of a bull elephant. It makes voices of most men sound like the twitter of winged things. And its liquid tones, like an old bass viol, set good women weaving like serpents to the flute.

For all this formidable equipment, Jimmy has moods of wanting to retire. Doesn’t think it dignified for a man to spend his whole life making up the mugg and strutting in costume. He wants to be a farmer on acres of cows and horses, pigs and potatoes. But he isn’t interested in none of them there little California nutsy, fruitsy farms.

“California is the perfect home for the screen actor,” says he. “In London you get up in the dark and you come home in the dark. In California . . .”

“You get up with Sunshine Simmons and come home with Sunshine Simmons.”

“Right,” said Jimmy. “And Sunny Simmons belongs with show business. She is a dedicated actress. I don’t mean she is gaga,” he illustrated by bugging his eyes and looking intense. “She just lives in her work. Up at six, off to the studio, home at seven, studies her script, falls asleep.”

Naturally she asks Jimmy’s advice on interpretation of roles.

“Naturally,” said Jimmy, “when I tell her, she knows that is the one way not to play it.”

On second thought, Jimmy said he might not retire to a farm but become a director; he’s so sharp at telling others how to act.

When Jean is not working, she sleeps right through the day, or until awakened by husband, bearing breakfast tray. In the evening while he toils over the hot stove broiling steaks for her, she does Gene Kelly routines around the swimming pool until supper’s ready.

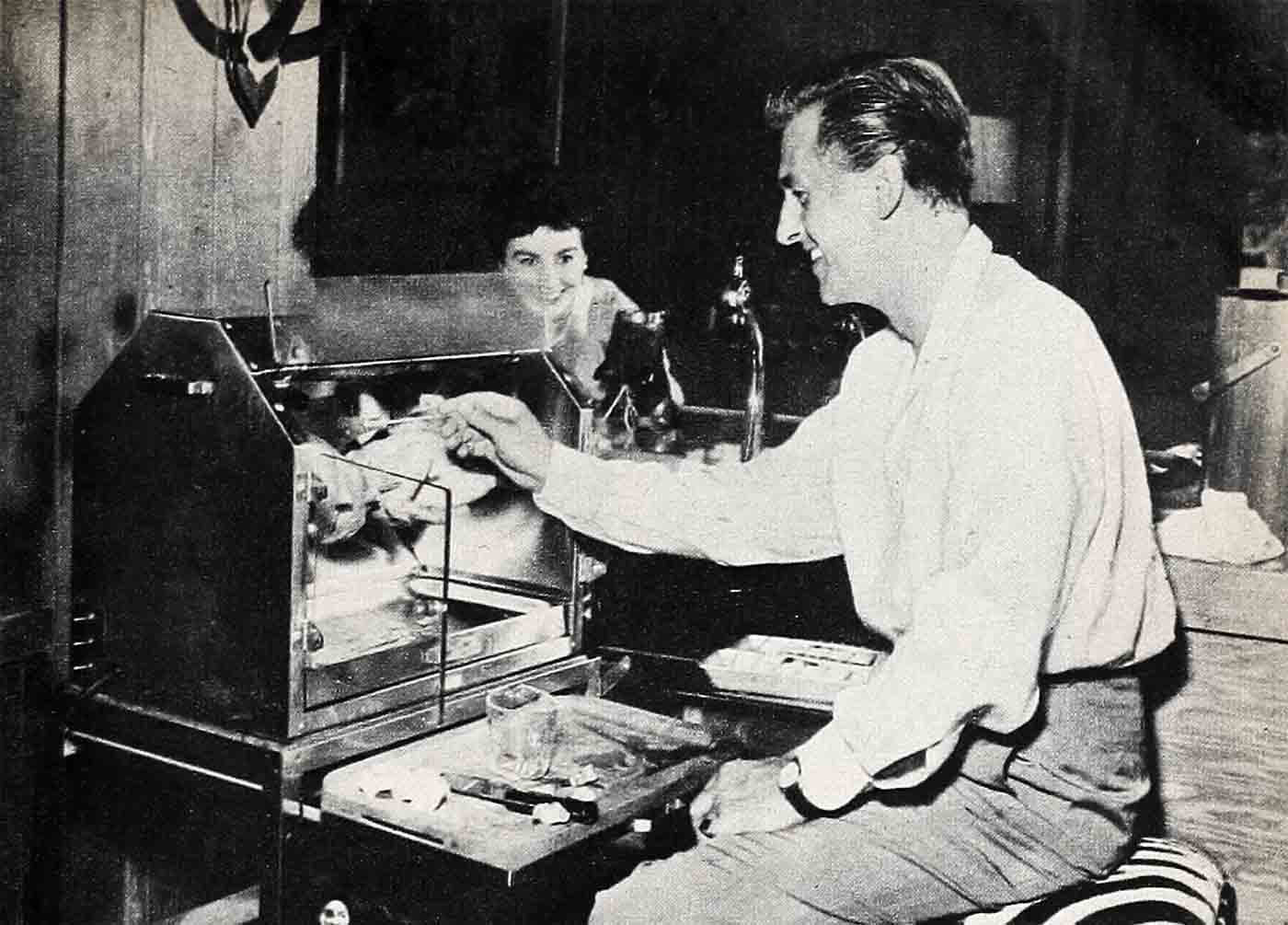

After steak-stuffing, the carnivorous couple often look at television programs. They do not disagree even on this source of marital friction. They have two sets. He looks at the fights. She looks at Lucille Ball.

A perfect home is not right without pets. Jean has five.

“Tm fifth,” says Jimmy. “My colleagues are two toy poodles named Young Bess and Old Beau; two Siamese cats whose names I can’t give because they are not approved by the Breen office.”

Anything more you’d like to ask Doc Granger?

Prescription for a perfect marriage? Sure: Two television sets and Jean Simmons.

How to ruin a beautiful friendship?

That you already know.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MAY 1954