Open Letter To Frank Sinatra’s Kids

Dear Nancy, Frankie, Jr. and Christina,

Not too long ago a friend of ours saw you at Disneyland with your Pop. It wasn’t the first time you’d all been there together, and our friend had heard some odd reports about your other visits. So for an hour or so he tagged after you, watching to see if the rumors were true.

And they were. While you three raced from ride to ride to sideshow to popcorn booth, grinning and giggling and carrying on as if you weren’t almost all grown-up, having a ball for yourselves—your father stalked after you, his eyes worried, his forehead creased in an almost nervous frown. When he climbed on a fast ride next to Nancy, his arm went around her as if he didn’t trust safety-belts and good engineering—all alone, he was going to keep her safe. When Frankie wanted cotton candy, your Dad’s hand got in and out of his pocket in record time, tossing him the quarter. And bur friend heard him say anxiously, “You girls want some, too? No? You sure? Well, maybe something else—?” And that slightly nervous air never left him all afternoon.

That’s pretty funny, isn’t it? Because if there’s one thing your Pop is known for, it’s hangin’ easy. No matter where or when or with whom, he just isn’t the anxious type. He’s relaxed as—as Perry Como. He’s famous for it.

But not with you. Oh, don’t get us wrong. He knows you love him; he knows you’re good kids. And that’s exactly why he looks so tense. He’s afraid to hurt you. Afraid that one day you won’t have a good time with him. Afraid that no matter how good a father he is—he won’t be the best. It puts those lines in his forehead. It’s the one thing on this mortal earth that scares rich, charming, talented, top-of-the-world Frank Sinatra to death.

He might hurt you. And it’s true, he’s got reason to worry sometimes. You know he’s got a suit on against a national magazine that ran a three-article series about him. He claims that he found twenty-three factual errors in the first article alone. Mind you, those errors couldn’t have hurt his career or his social life in any way. He could have ignored them and saved himself the dough and the publicity and the bother of suing. But when he read that article for the first time he threw down the magazine and turned a white face to the other guys in the room. “Don’t those jokers know I’ve got kids?” he bellowed. “Big kids. They can read. What am I gonna tell them when they read these lies about me? What are they gonna think?” He ran his hands through his hair. “I’m suing them,” he said. “I can’t just sit back and let the kids get this stuff thrown in their faces in school.”

So he’s got a suit on. And now he’s got even more to worry about. His name has been dragged into one of the messiest scandal suits that ever made front-page news. You know what trial we’re talking about. You must know—because you can read it in all the papers, and not even your worried father can do a thing about it.

As low as you can get

That’s why we wanted to tell you kids some other things we know about your Pop. Things we’ve heard about here and there, in bits and snatches, little stories about him sent to us and told to us by a lot of people—some famous movie stars, some newspaper reporters, some nobodies. It’s about the side of your father that doesn’t make headlines. . . .

Like that story we heard from a friend of Lee J. Cobb’s. Maybe your Pop wouldn’t like it to get around, but it’s a cinch if Lee or one of his pals hadn’t told it, no one would ever know about it—because your Pop would never open his mouth!

Lee is sitting on top of the world now, of course, but two years ago, he was flat broke, just divorced, out of work with no prospects, and on top of everything else he was in the hospital with a heart attack. That was in July.

So anyway, as far as money went—and as far as his mood, too—Lee was about as low as you can get . . . that day your Pop phoned him at the hospital. The call took about fifteen seconds and went, “Hello, this is Frank Sinatra. Thought I’d let you know I’m coming over!”

Lee thought someone was kidding him, because Lee hardly knew the guy.

But that afternoon and every afternoon after that, Sinatra went straight to the hospital after work. He was making The Tender Trap as I recall it. Anyhow, he didn’t come empty-handed. He brought books and flowers, and he got lists of what Lee liked to eat—and was allowed to eat—and I think he even sent to New York for some stuff once. But more than that, he brought that famous Sinatra happy-mood charm with him. You know what we’re talking about! He never even gave Lee a chance to brood. Every day he had something else to tell him about how so-and-so said what a great actor Cobb was and how many parts he had waiting for him. Maybe he even made it all up. I don’t know. All I know is when Lee got out of the hospital, your father’s car drove Lee to the Sinatra house, and the Sinatra servants looked after him and Sinatra told him to hurry up and get well because he wanted Lee to direct a movie for him.

Anyway, you know what happened. Lee got better—oh, I should add when it got too hot to bear in Palm Springs Sinatra moved Lee to an apartment in Hollywood and picked up the tab for that, too—and all of a sudden everyone in town wanted Lee. He’s too busy acting to direct, I guess you’d say. But let me tell you, if Sinatra asked, Lee’d drop the juiciest part this side of Oscarland, to do him a favor. I mean any day of the week. He’s paid back the money Sinatra laid out long ago. But the rest of what Lee owes him—that’s not the kind of debt you can pay off. Except maybe by letting it get around what kind of a guy your Pop is.

So anyway, that’s the story. Oh, by the way, when I said your Pop hardly knew Lee, I meant they had met at a party, said hello—maybe had a drink—and that was it. Period. So what I’m getting at is—if a guy will do something like that for a stranger—what will he do for his friends?

They called him “The Voice”

This next story came to us in the mail a couple of years back, and the woman who wrote to us said she’d rather not give her name because she’s a married woman with children of her own now, but she could still remember—like it was yesterday—when it happened. She was a high school girl then, in Gary, Indiana. That was back about eleven years ago—you weren’t even born yet, Christina!—and all the kids in Gary had walked. out of all the high schools on strike, because there were Negro kids going to the same classes. She wrote that she didn’t remember clearly how they got so steamed up, but there were an awful lot of rumors going around that the white kids were being discriminated against, and they were lowering themselves by sitting next to the colored kids—and a lot of the parents talked that way, too. Anyway, one day they were in school, and the next they were on strike and the papers were full of it, and the Mayor was making speeches and Gary, Indiana, was headline news all over the country.

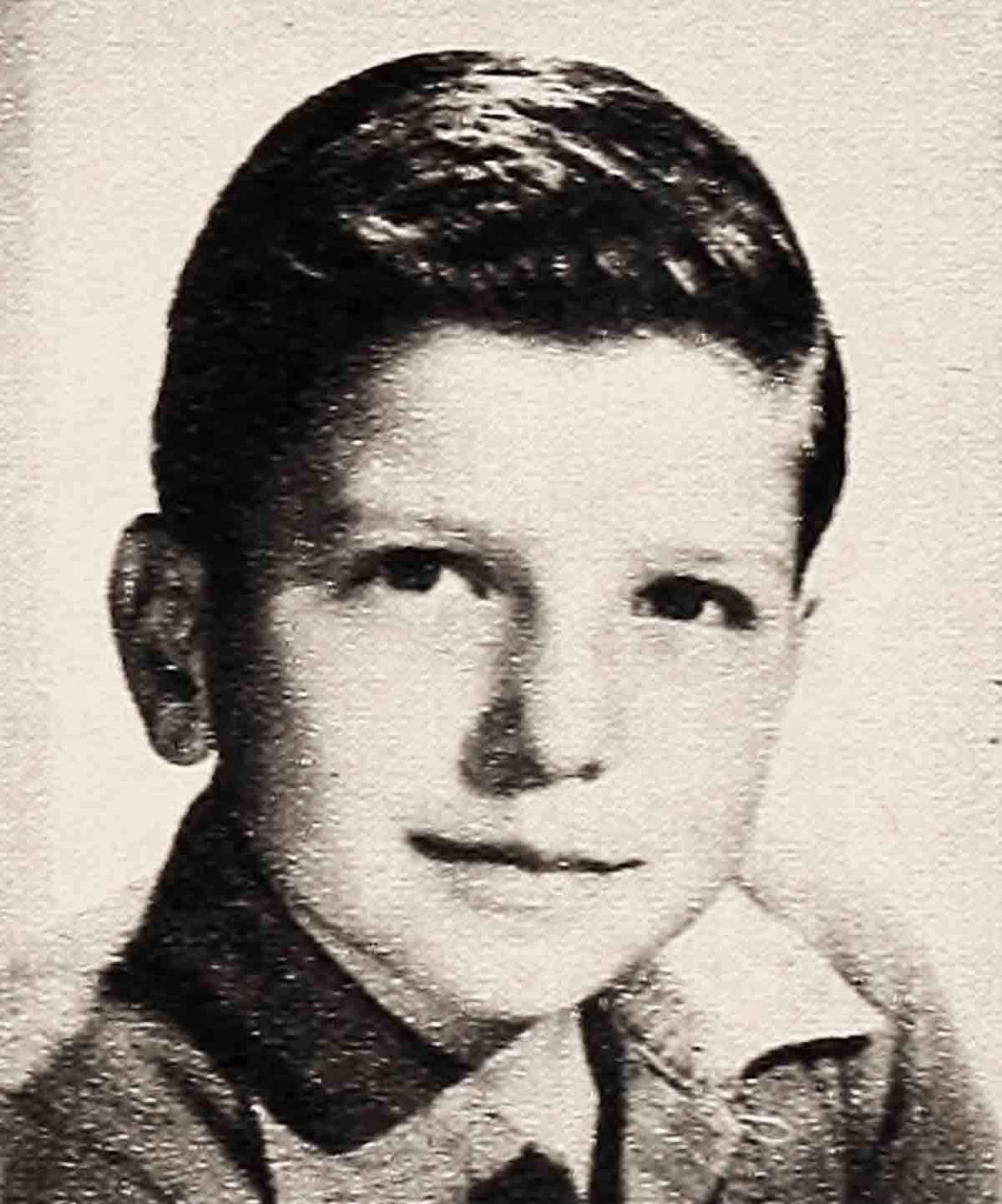

Well, the strike hadn’t been on more than a couple of days when the kids got word that Frankie was coming out to Gary to talk to them. Boy, I don’t know if anyone can appreciate what that meant then. That was when they called your Pop The Voice and he wore those floppy bow ties and looked so skinny, and the girls wore sloppy joes and saddle shoes and used to scream and faint in the aisles—just like over Elvis and Pat, only more so! I mean really faint. This woman who wrote to us said she did, too, once, right in the PARAMOUNT THEATRE in New York watching your Pop, and the police carried her out and gave her smelling salts. Anyway, what I mean is, Frankie was the biggest man in the country, the way no one ever has been to kids since. And I don’t know how many hundreds of thousands of dollars he made every time he got up on a stage and opened his mouth, and also he was making movies at that time. But here he was, ducking out of everything to come to Gary.

So sweet and good

Well, the strike leaders told all the kids to stay away from the Municipal Auditorium where he was going to talk—that’s what the strike leaders told the students to do. But of course who was going to listen to a strike leader say something like that? It didn’t make sense, the kids thought. So they sneaked over anyhow, some six thousand of them! The house was packed.

Then Frankie—your Pop—walked on stage. And he started to talk. “I guess,” this married woman wrote us, “I’ll never forget that talk as long as I live. I mean, who’d every heard Frankie say anything? Well, he told us the strike was a bad deal, bad for us, bad for the country. I remember him saying, ‘It’s a Nazi trick to divide and rule by pitting race against race. That can’t happen here because we won’t let it.’ He told us what I’d been suspecting anyhow, personally—because otherwise why would those strike leaders have tried to keep us from listening to our Frankie?—anyway, he told us that the strike had been taken out of our hands and was being run by outsiders who didn’t really give a darn for us and our school. He was so intense and concerned, and we all knew how much he cared.

“And then,” this woman explained in her letter, “Frankie said, ‘Do me a personal favor. I came down here to ask you to go back to school. Please do it.’ ”

Well, he sounded so—sweet—and good. Some of the kids there started to cry. Then he sang something to close the program—she doesn’t remember what, but I have an idea Nancy, Frankie, Christina know it was probably The House I Live In, because it was around then that he made that short on tolerance. And got a special Oscar for it!

Anyway, a couple days later they all went back to school.

And I think it was on account. of Frankie. “I know,” that lady wrote in her letter, “it just would have killed me to have him ask me to do something and then not do it. And he’d been so nice, not bawling anyone out, just telling us we were bright and smart—it made us feel that way.”

Did you know your Pop got an awful lot of awards that year for that kind of thing? Almost a dozen, I think. But the best award he ever got was just all those kids going back to school like he asked them to that day, and learning to live in peace.

He knew he would get well

There are other things somebody here and there remembers about your Pop. Sammy Davis, Jr. for instance. They all came around when Sammy lost his eye. The crowd in his hospital room was made up of some of the most famous faces in Hollywood. And they put on a good show. They laughed it up for hours. They gave Sammy all the latest gossip, all the newest jokes. And they looked anywhere—at the walls, the ceilings, under the bed—to keep from looking at the hole where his eye should have been.

They had all gone home when Frank walked into the room. And Frank didn’t come in grinning. He walked in with his eyes dark and serious, and they didn’t look up or down—they looked Sammy straight in the face. “Well,” said your Pop, “what’s it gonna be now?”

And for the first time since the car crash, for the first time since he knew he would wear a patch for the rest of his life, Sammy Davis, Jr. let the smile drain off his face, let the cheerful lies stop pouring out. For the first time, he talked about what was going to be—his terror of facing the world again; his fear that a one-eyed singer was no one anyone would want to hire.

And Frank fed him no lies. For hours they sat and talked about the problems that lay ahead. About the road that wouldn’t be easy any more. And at the end, when the nurse came in to tell Frank it was time to leave, he stood up slowly, stubbed out his cigarette and smiled for the first time. “You and me, Sam,” he said. “We’ll make it.”

He said it with the voice of a man who had sat on top of the world—and felt it crumble away beneath him. A man who read his name in a newspaper’s cynical list of THINGS THAT NO LONGER MATTER. Who had been called every name under the sun and found the hardest one to take was—has-been. A man who had given up his wife—your Mother—and a home to chase a dream of romance around the world—and had come back alone.

You kids’ll be able to understand that a little bit better when you’re older. Just remember for now—though I guess you know it pretty well, your Pop never gave you up. Anyway, when the door closed behind Frankie, Sammy Davis, Jr. sank back into the pillows. If the doctors hadn’t warned him against it, he would have cried. For the sick fear that had come to him each time the gay, laughing cheerer-uppers had left, was gone. For the first time, he knew he would get well. . . .

The worst you can say . . .

I just read a bit in the papers about Frank Sinatra socking some guy. I’m not defending your father for using his fists too much—sure, he swings when he ought to talk it out instead. But I do say, near every time—he had a reason. Like the time he nearly killed a guy in a nightclub for asking who was the “broad” with Sinatra. It sounds like a fairly innocent question—even though that’s not such a nice word to use!

Only thing was, the guy was a columnist. And the broad was Judy Garland, whose husband Sid Luft, was on the other side of the country on business. And Judy was six months pregnant!

Hours later, Frank was still raving about t. “Sure I hit him. If I hadn’t hit him, he’d have had it in his column that I was dating Judy while Sid’s out of town. For Cripes’ sake! I wasn’t with Judy—we were both in the same crowd, that’s all.”

By the way, did you know about that time your father was in a crap game?

I’ve laughed about this for years.

The way that story goes, for years your father has been eating at one big Hollywood restaurant. Always sat at the same table, always had the same waiter, always tipped high wide and handsome.

So one night Frankie walks in and sits down and the waiter doesn’t make a move to serve him, but gestures for another waiter to take his place.

Sinatra says, “What’s the matter, don’t you want to wait on me any more?”

The waiter shook his head real sad-like. “Sure I do, Mr. Sinatra, but I lost you to him in a crap game last night. You’re his till June . . .”

Look, kids, we could go on for pages like this. There are so many of these stories it could fill a book. Your grandmother Sinatra could tell you about the winter in Florida he gave her the clothes the house. Phil Silvers could tell you about the time Sinatra saved his act and his career, and Bela Lugosi—had he lived—could tell you about how everyone in Hollywood thought it was noble of Mr. Lugosi to commit himself to a hospital to have his drug addiction cured—but your Pop was the only one who phoned him there and asked if there was anything he could do. Everyone else was too scared people would think they were friends of a junky. There’s a New Jersey kid who had leukemia who could tell you about the trip Frankie made to see her—halfway across the country. There are the Underprivileged Children of England who have summer camps now because an American named Mr. Sinatra got the idea of doing a benefit for them and spent thousands or dollars of his own money making the arrangements—with no less a partner than Prince Philip. There are the parents of a little boy in L.A. who took their three-year-old to the docks at San Pedro to see the ships go in and out. The child fell into the deep water off the end of the pier, and before anyone else could move, a skinny guy the comedians all called anemic—this was back in ’45—had made a twenty-yard-dash across the dock, dived into the water, and pulled the child to safety. He could have made a lot of capital off that one. He didn’t. The comics went right on making jokes about how he’d split in two if he bent from the waist, and your father grinned and let them.

But you don’t have to hear all those stories. Strictly speaking, you didn’t have to hear any of these—we know were no telling you anything new. You know your father pretty well. Nancy, you go with him on tours, to premieres. Frankie, well you get your music lessons from your Pop. Christina, you get teased about being the Miss Moneybags of the family practically every night of every week. Because your father is around that often. To make sure nothing goes wrong for you kids. To keep you as safe as a guy in his business can.

No, this isn’t to tell you anything new. It’s just to say—we don’t know what they’ll be printing about your Pop in the next few weeks. And we don’t care. But whatever it is, true or false, clean or dirty—don’t get the idea you ever have to apologize for your Pop.

It’s the scandals that make the headlines, every time. But it’s the record on the other side of your Pop, the side that gives not just his time and money, but gives of himself to friends and strangers alike, over and over again, that is going to count in the end. . . .

Yours sincerely,

DAVID MYERS

Frank’s in Paramount’s THE JOKER I WILD, UA’s KINGS GO FORTH and THE PRIDE AND THE PASSION and Columbia’s PAL JOEY.

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1957