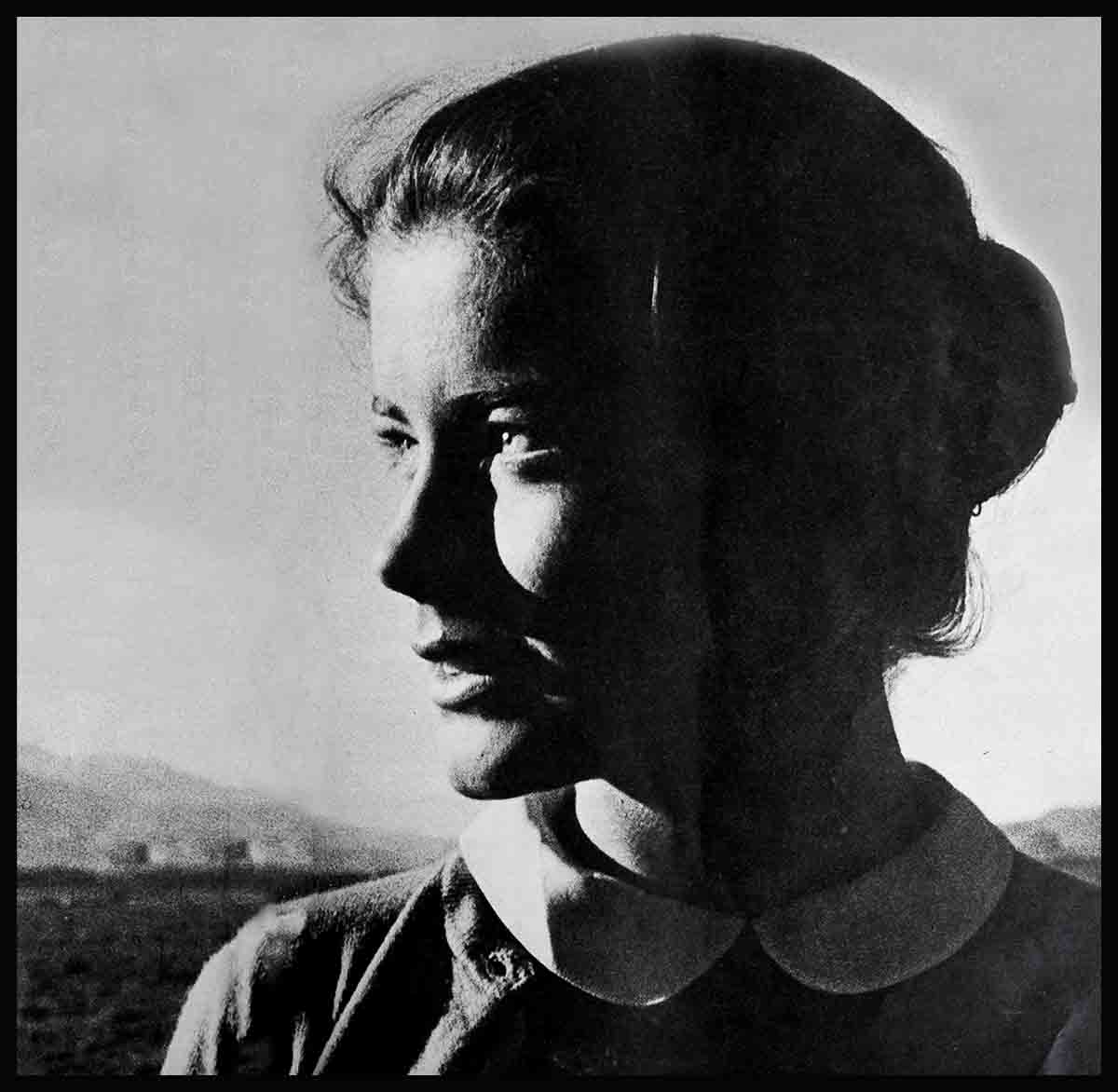

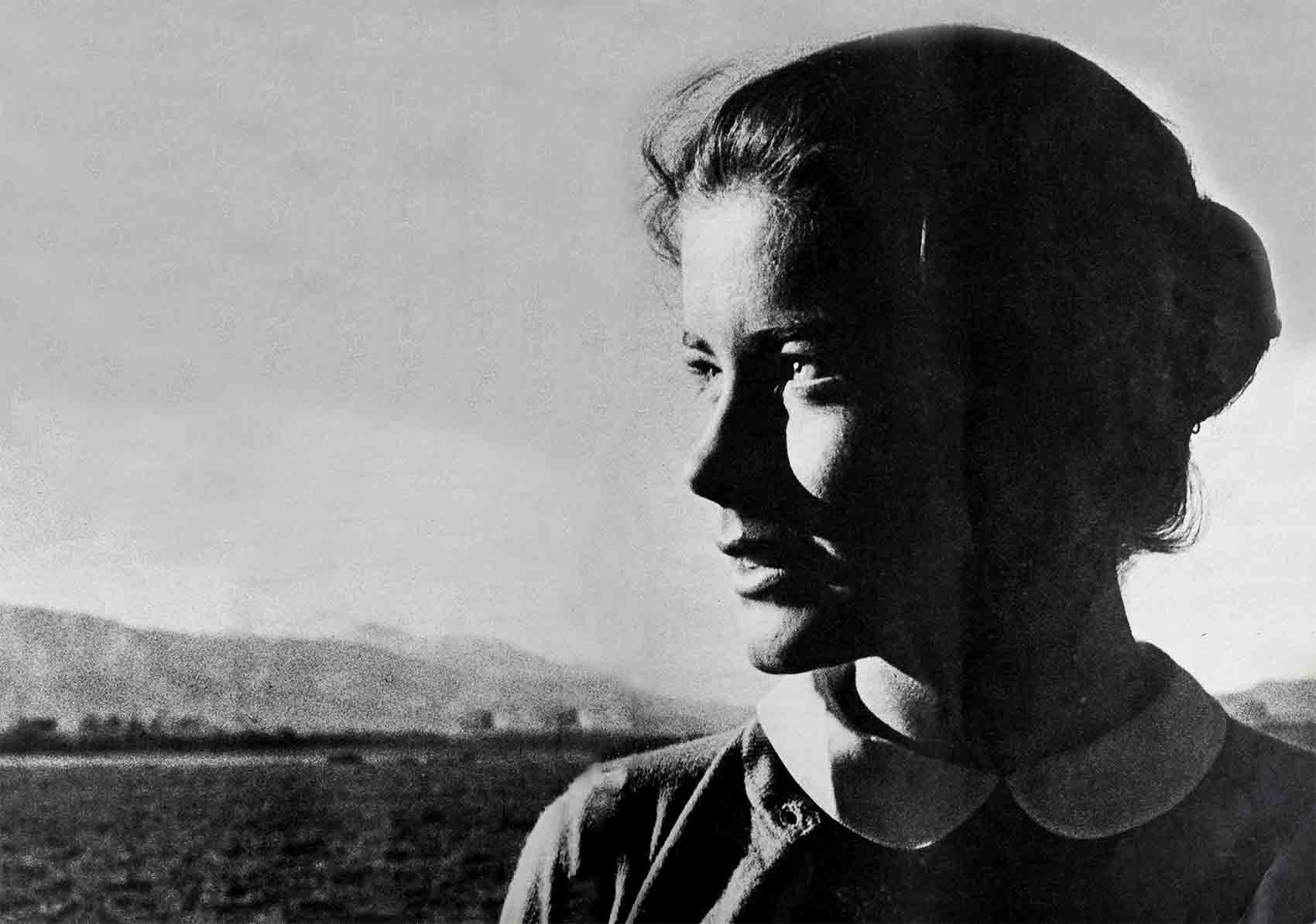

Dolores Hart’s Own Story

Dolores Hart awoke early this late-spring morning. She awoke, and she smiled, for this was to be the most joyous day of her life. Today she would bid her goodbyes to one world and make ready to embrace another. Today she would leave California, on her way to enter a convent . . . and her lifelong dream—to become a nun—would have, at last, its beginnings.

She kneeled for a while at the side of her bed. Silently, she prayed: “Oh Lord God Almighty, Who has safely brought me to the beginning of a new day, defend me this day by Thy power, so that I may not only turn away from all sin, but also that my every thought, word and deed may proceed from and be directed according to Thy Will. . . .” And then she added a special prayer of her own: “I thank You, dear God, for the life You have given me. I dedicate that life to You from this day. And I offer up my joys, my ambitions, my all. Give me the strength, this I ask of You, please, dear God, to be able to follow my true calling. . . .”

She rose, then, and washed, and dressed. As she washed, she carefully avoided looking at herself in the mirror. There would be no mirrors at the convent, she knew. Vanity, any vestige of it, must be left behind. And so, this pretty girl, an actress, a Hollywood starlet, so used to having all manner of men and women rush up to her with handmirrors before a scene, so used to sitting in front of a bulb-framed mirror and staring to see that the lipstick was properly applied and that the mascara was not smudged—now avoided her own mirror. Not looking at her face this morning. As she would be living from now on. As she would never look at it again.

She dressed simply this morning—in a plain dress that was a particular favorite of hers. Her only dress, really. Since, just the day before, she had finished giving her other clothes away. To friends. And charities. Along with the rest of her possessions—everything.

And now Dolores walked into the garden of the pretty little hilltop house where she had lived these past few years. For a look down the hill. A last look. At Hollywood.

It had been good to her, this town. She had no complaints. It had treated her fairly. It was filled with people who had been nice to her. It was a rich town, filled with every luxury known to man. There were some people in it who had traded their souls to taste some of that luxury. It was a strange town—happy, sad, clean, dirty, moral, perverse. Hollywood.

Fortunately, however, Dolores had known only the best of it. And had she continued in that town, it was clear that the best would have mounted for her—she would undoubtedly have been a true star one day, truly wealthy, truly happy in the most earthly sense.

This she sensed. But this she could not have cared less about. Not now, this day, this moment of this particular morning. As she looked down at the so-called magic town, as she thought to herself, simply: “The life you offered me, Hollywood, held no meaning for me.”

After a while, her eyes began to rise . . . above the pink roofs, the lushly green palms . . . to a patch of sky overhead. And she whispered now: “Give me the grace to be Thy faithful soldier, so that by fighting the good fight of faith, I may be brought to the crown of eternal life by the merits of Thy son and our Savior, Jesus Christ.” Then she turned and went back into the house. To wait for the car that would soon come to take her to the Los Angeles airport. . . .

Vince Edwards said of Dolores’ decision to enter the Connecticut convent: “The news about Dolores came as no surprise to me. A girl that good and that religious was bound to enter a convent. I have never known any other girl in my life as wholesome and honest as Dolores. We dated a lot when we were both under contract to Hal Wallis. There was nothing serious. She was doing important things—and I wasn’t. My biggest checks came from the unemployment office. That didn’t bother Dolores. She spent most of the time boosting my morale and uplifting me spiritually when I needed it the most. A lovely, beautiful girl, she will make a wonderful nun. I know she is truly happy—and I’m very happy for her. . . .”

Dolores listened intently, that next morning, as the Mother Superior of the Regina Laudis Monastery in Bethlehem, Connecticut, spoke to her and the other girls gathered in the main room of the lovely old building. “The period of postulancy must be a period of testing and examination,” said the Mother Superior, in gist. “We will study you girls and learn about you—and you will study us. I want you to know early what you are giving up in the world. The vow of chastity, I emphasize, is a choice made between human love and divine love. Poverty is the detachment of heart more than a privation of comfort. But I stress obedience as the hardest of the three vows. You must give up your will for the will of God as manifested to you by those appointed to lead you to God. It is not the big things you will find hard. It is the giving up of self in everyday life.”

Dolores listened as the Mother Superior explained next how the period of postulancy would last for six months, how the black veils the girls would soon be given would then be exchanged for white veils, the sign of the novitiate—how a number of the girls present would drop out, inevitably, before the six months were over—how it was a sad but true fact that not everyone could cope with the rigors, emotional and physical, of convent life.

It had been no secret to Dolores these past few months that there had been those who had opposed her entering the convent.

“She’s Hollywood-bred,” they’d said. “Trained to fantasize. Trained to play one role one month, another role the next. Trained to show emotions that are only surface, skin-deep. Trained to a glamour that is indelible and to habits that will be difficult to relinquish!”

Thankfully, such opposition had been in the minority.

Thankfully, there had been those who had known Dolores and who had supported her desire to enter the convent.

A nun at Corvallis High School, for instance, from which Dolores had graduated. Who now wrote to high Catholic officials: “She has always wanted to play good girls on the screen. She considered it a challenge because she felt it was much harder to portray a nice girl—and much harder to live like one off-screen. She used to say that a good girl has much more old- fashioned guts, if I may use the vulgarism, than her opposite. And she’s right.

“Hollywood hasn’t changed her. She stops in here often. She always says, ‘I have too many of you Sisters who are interested in my career. I’ll never do anything to embarrass you, I promise.’ And she didn’t.”

This letter. Others. They helped swing the tide for Dolores.

And as she sat here now, this first day of her postulancy, in the large room of the Connecticut convent, with the others—she begged, silently: “Let me not disappoint those who have placed so much trust in me. And, above all, let me not disappoint Thee.”

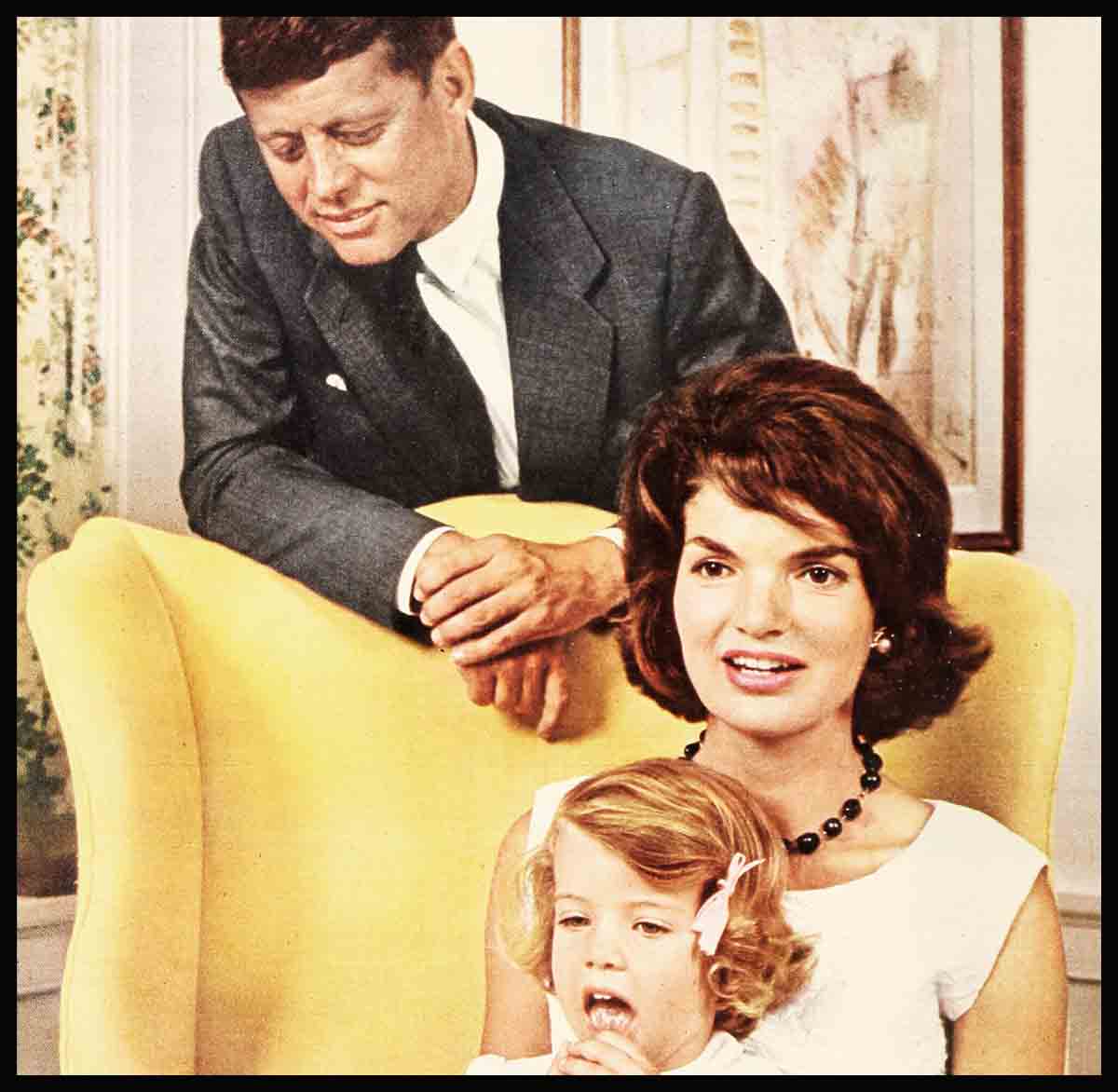

Two men in her life

Elvis Presley said of Dolores: “I first met Dolores about six years ago, when I played her co-star in her first picture. She was then, and is, the nicest girl I’ve ever met. She had every virtue—kindness, charity, good breeding and there was not one mean bone in her body. She was always playing jokes on me. We worked together fine. I wish her all the happiness that I know this move will bring her.”

Ty Hardin: “I used to date Dolores. We were never serious. She was Catholic and I’m a Texas Baptist—the two just don’t go together. But she sure is one of the nicest people I’ve ever known. I have found in my own life what joy there is through Christ—and I’m sure Dolores has, too. She has my wishes and my prayers. I know they will be answered, for there aren’t many Texas Baptists praying for Catholics!”

Her Protestant childhood

She had not been born a Catholic.

As a little girl she’d lived mostly with her grandparents in Chicago and had been initially raised in the Protestant faith.

“But,” recalls Dolores, “one day, when I was about eight years old, I found myself in a Catholic school. How I got there was sheer accident. To get to any of the other schools in the neighborhood, I’d have had to cross three sets of streetcar tracks, but not the Catholic school.”

It was an unsettling change for the little girl at first. The ritual, the daily Masses, the prayers in Latin—all of this confused Dolores at first. But. eventually, as she says, “I began to find myself growing to love this new religion, and growing more and more dependent on it.”

Dolores was nine when everyone thought, suddenly, that she was going to die. She’d come down with a case of strep throat, she’d reacted badly to a then-new miracle drug, her body had swollen enormously—she’d been conscious, but she hadn’t been able to move or speak.

“I remember,” says Dolores, “how one day, lying there, I could hear some of the family discussing my funeral arrangements in the next room. The next day, I remember, a little friend of mine came over to the house and I heard her say to my grandmother, ‘Don’t cry, because after Dolores is gone I will bring over my toys and play here and then you won’t be lonesome anymore.’ The whole feeling was one of death—up until a doctor gave me a second J drug and. slowly, I began to recover. But even before this . . . I wasn’t afraid. I realized, you see, that my life wasn’t really mine, that earthly life was only a small part of eternal life. I’d learned in my classes that God loved me and was going to take the best care of me, because He had created me for some reason. So, whatever happened to me, I knew it was God’s will . . . and entirely for the best.”

When Dolores was eleven, she was converted to the Catholic church.

And her faith since then, as she says, “has helped me in many ways.”

More than once, in fact, it has been through nuns—their kindness, their understanding—that the help has been given.

There was, for instance, the time when Dolores was thirteen, when she longed to become a volley ball player at school: “Something happened, however, and I didn’t make the team. My dreams of prizes and glory all went out the window. My pride was hurt. I might have been very unhappy—had it not been for my faith and the patient teaching of the nuns, who showed us that everyone has his limitations and must accept them.”

Priests helped Dolores back then, too.

“I was in my senior year of high school,” Dolores recalls, “when this boy I was going with asked me to marry him. I nearly said yes. I wanted to say yes. It was quite the fad at school. I guess, to have an engagement ring before you graduated and I—and a few other girls—were quite caught up in this fad. Fortunately, however, a priest suggested to me and the other girls that we attend a retreat before we gave our boyfriends our final answers. At the retreat, the priest really set us straight on the subject of marriage. He talked about the responsibilities we’d be facing, the seriousness of the step. ‘Just imagine at your ages,’ he said, ‘wondering what happened to the starry nights of bliss while you’re all involved in those two o’clock feedings, keeping the house clean, washing out dirty socks!’ Oh, we resented what the priest said. At first. It seemed that he was shattering all our illusions. But it didn’t take long for most of us to realize, after a while, that he was right. That we just weren’t ready. That life was young, we were young—and that there were other things ahead for us first.”

For Dolores it was Hollywood. . . .

A multi-colored blush

Hal Wallis, the producer, tells of his first meeting with Dolores: “Some friend had sent me Dolores’ picture. My assistant, Paul Nathan, confirmed that she looked as good in person as her picture. I phoned her mother and asked for Dolores.

“As soon as she came into my office, she broke out in a multi-colored blush. In our business, you don’t find many girls who blush. I knew that this was someone different, someone with that Grace Kelly appeal—someone with class.

“In all her years in Hollywood, she never changed. The last time I talked with her she was blushing. A beautiful girl, inside and out. I hate to lose her—but she’s got a much better offer now, and no one is happier about it than I. . . .”

The years in Hollywood were bittersweet for Dolores.

On one hand, she was the girl who had everything. She worked steadily. She was extremely popular. She dated the cream of the town’s goodlooking bachelor set. Recently, she had met and become engaged to a young Los Angeles businessman named Don Robinson—soon she would marry him, soon life would be perfect.

Except that somewhere deep inside Dolores, in her soul of souls, there lived the feeling all this time that something, one thing, was missing from her life—lost in the glitter that had become her life.

It was a sad period for her, as those who were really close to her will now tell you.

Says one friend: “Despite the smiles, despite the outward gaiety, there were times when—alone with Dolores—one sensed a vast unhappiness. Or perhaps disillusionment is the better word. She became disillusioned, for instance, with many of the people in movies with whom she had grown up professionally. Their hasty marriages disappointed her. Their hasty divorces hurt her. Their fastness—their desire to speed through life—was beyond her comprehension.

“She said to me once, and I’ll never forget it:

“ ‘Why do so many of these people live as though they expected to die before the day ended? Why do they act as though they have to get in every pleasure possible at once—try everything quickly—as though they may not get the opportunity tomorrow or the next day?’

“Then Dolores shook her head, and said:

“ ‘I know that the length of my life is entirely in God’s hands. He may take it today, or He may let me live another sixty or seventy years, so that I’ll have to live with the results of whatever I’ve done for a long, long time. I just can’t live for the moment with the assurance that I won’t have to answer for my conduct on this earth.’ ”

Says another friend of Dolores’: “The conflict inside her existed for a long time, and long before she came to Hollywood. Her desire to become a nun goes back to her earliest days in that little Catholic school in Chicago when she would say to herself on one hand, ‘If only I could become one of Christ’s brides—this would be my greatest joy,’ and then on the other hand would say, ‘But I am not worthy of that happiness.’

“So she followed what she thought to be her destiny. She went to Hollywood. She made her movies. She collected her hefty paychecks. She went to the parties, signed the autographs, posed for the newspaper and magazine photographs. Eventually she met a nice young man, a really nice guy. He was in love with her. He asked her to marry him.

“The truest love”

“And it was really only after her engagement to Don Robinson that Dolores knew, finally knew, that what had been lacking in her life was the truest of all loves, the unabashed declaration of her love for God.

“One night, not long after the engagement, Dolores had a long talk with Don. She explained everything to him. She gave him back his ring.

“And the next morning she announced, quietly, to those of us close to her that she had made her decision, to become a nun—‘if they find me worthy,’ as she said. . . .”

Says Don Robinson: “I know Dolores is very happy. And I’m happy for her. That is all I can say. There is nothing more.”

It was evening now, the end of this first day of Dolores’ postulancy. She was at peace.

The lights had just been turned out and Dolores lay on her cot in the convent room that had been assigned her.

From down the corridor she could hear one of the other postulants, sobbing.

Dolores remembered what the Mother Superior had said to them all earlier that day:

“It is not the big things you will find hard to give up. It is the giving up of self in the details of everyday life . . . It is not easy to be a nun. It is a life of sacrifice and self-abnegation. It is a life against nature. Poverty, chastity and obedience are extremely difficult.”

Dolores continued to listen to the sobbing, as it cut through the early-evening quiet.

“Please God,” she thought, “help her not to cry. Help show this girl the way, Your way. Help show her, as You have shown me, that the past was nothing as compared to what our lives will be from this day on. this most beautiful of days.”

Dolores smiled, after a while, when the sobbing stopped.

“Oh God, thank You, thank You,” she thought. “Thank You for loving us all . . . as we love You.”

And then, closing her eyes, still smiling, Dolores repeated her Evening Prayer, over and over, until she fell asleep. . . .

—MICHAEL JOYA

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1963

zoritoler imol

3 Ağustos 2023There are actually a number of particulars like that to take into consideration. That may be a great point to carry up. I supply the ideas above as basic inspiration but clearly there are questions like the one you deliver up the place a very powerful factor will probably be working in sincere good faith. I don?t know if best practices have emerged around things like that, however I’m certain that your job is clearly recognized as a good game. Each girls and boys really feel the impression of only a moment’s pleasure, for the remainder of their lives.