The Big Man Comes Home—John Wayne

A large man in a white shirt and apron opened the door and stepped out on the porch.

“Good evening, Mr. Wayne,” he said. And then he grinned. “Welcome home.”

“Thanks, Scotty,” John Wayne said. “It’s good to be here.”

And then he threw himself into a comfortable chair, dropped his hat on the ground beside him and lay back. Through narrowed eyes he gazed about the land that was his and the house that he hoped would be his final home.

It was no pasture land. Seven acres of neatly clipped green grass stretched out and curved in a broad sweep to the top of a hill on which sat the house, almost obscured by pepper trees. He had parked the car and cut off across the lawn, past a caretaker’s house, a riding ring and a series of horse stalls and a stable. Then he had climbed to a wide play area beside a large swimming pool. He had inspected the water before he trudged up a steep incline of fieldstone steps that hugged the contour of the hill.

Here at the top was the house. A large house of fourteen rooms, two stories high and built to complement the hill top and take advantage of the many trees.

Yes, it was a homecoming. This was the first evening in more than two years that John Wayne had come home to a house that was really his. During that time he had lived in rented houses and had spent many months of his time in far places, mainly because he had no base in Hollywood that offered the security, comfort and peace he craved. He had owned this property for a long time, but until he started remodeling a year ago it had been a deserted barn on a hill of burned grass—a place that held unhappy memories—and he had shunned it.

Now it was a home again, and the girl who had made it so, Pilar Pallette, the Peruvian beauty he was going to marry and who had supervised the remodeling and decorating, would soon come driving through the gate to share dinner with him. John Wayne grunted in anticipation and he spoke aloud to nobody in particular.

“From now on,” he said, “I’m going to do all my traveling on this seven acres.”

And like an old movie stringing through a familiar projector, the journeys he had made, the junkets to far places he’d staged ran through his mind. They were episodic fragments of the past that he’d think of once more and then banish to some small storehouse in his head. Of course many of them were necessary to his movie work.

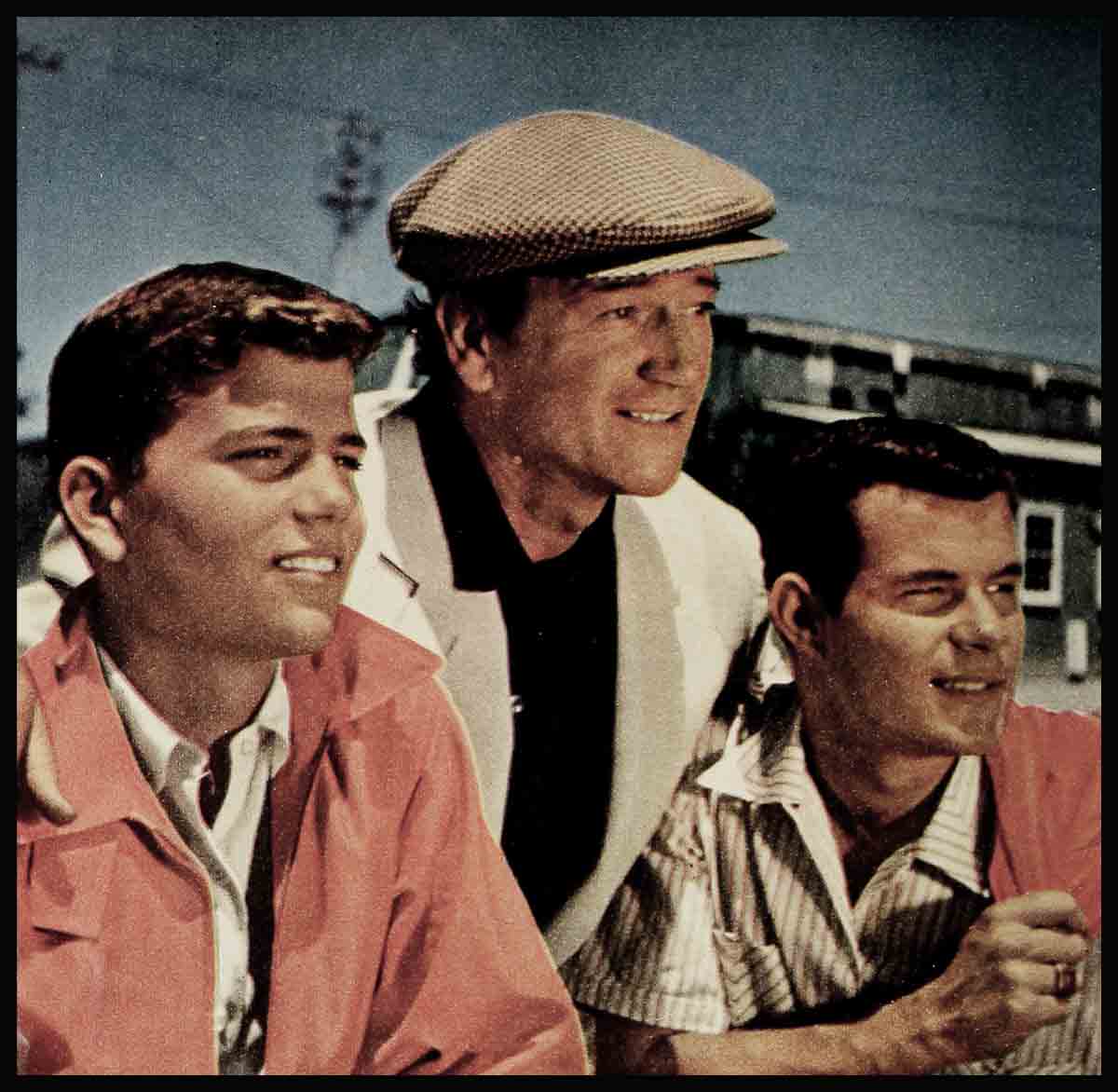

Location trips are hardly considered journeys by movie stars, maybe because about fifty per cent of the movies made in Hollywood require them. But it is interesting that to John Wayne these enforced departures from his base are the most trying. And he suffers like a lost dog for his fireside and family. Consequently, on every location trip he makes he somehow manages to have his four children go along for a short time, at least. They went to Honolulu for Big Jim McLain and to Mexico for Hondo and to St. George, Utah, for his latest film, The Conqueror.

But true to a code he established long ago, the two boys must work to earn their pocket money. In Mexico they had to keep the huge water tanks filled for the hordes of thirsty horses on the location. In St. George, Pat worked (on a union waiver) in the wardrobe department, and Michael, the nineteen-year-old, was selected by director Dick Powell to play an outpost guard.

In Mike’s scene, Duke, playing Genghis Khan, strides up to Mike, who, in the story, has been accused of laxity on his post. The father looks at the lad in great anger. He turns to an aide.

“Is this the man?” he asks.

“It is,” says the aide.

“Hang him,” says Wayne and walks away.

On the trip to Utah, the children, Mike, nineteen, Patrick John, fourteen, Toni, seventeen and Melinda, thirteen, came with their future stepmother, Pilar Pallette, who herded them in a private plane and delivered them to Dad’s doorstep. The kids adore Pilar and she is crazy about them.

John Wayne was a local boy. That is, he was raised in Glendale, a suburb of Los Angeles like Hollywood. Like most normal boys he wanted to travel, but the farthest he had ever been by the time he was twenty-one was the half-way mark to Honolulu. The trip was not blessed by authority. He wound up in jail.

He had been working in pictures as a laborer when he could get the work and money for travel didn’t come fast enough. So Duke hitch-hiked to San Francisco and smuggled himself aboard one of the Matson liners bound for Honolulu. With the surf at Waikiki almost audible in his ears, he secreted himself in a stuffy out-of-the-way locker. The ship set out to sea and as the hours passed the pleasant surf sounds were replaced by a more immediate noise, the growling of his own belly.

On the third day out, all of young Duke Wayne’s dreams of Honolulu sunlight and moonlight exploded and were replaced by a vision of food, so he staggered out, tagged the first ship’s officer he saw and suggested the fellow pinch him immediately as a stowaway and lead him to the dining room. This was done. Then Mr. Wayne was escorted to the captain, given a thorough tongue-lashing and the liner lay to while Duke was slipped to the deck of a freighter bound to San Francisco.

In the city by the Golden Gate, he was promptly locked up in the pokey and charged by the company that was later to enjoy his patronage many times—as the occupant of the best suite on the ship—with stealing a ride.

“I sure sweated out those three days in the can,” says Wayne, “but I got a real break just before I was to come to trial. I knew George O’Brien in Hollywood. His father was the Chief of Police of San Francisco and he came to see me. He went to bat for me and had the charges dismissed. And I walked out a free man with an admonishment never to board a Matson liner again unless I had a ticket. I thought of how close my stomach got to my backbone and decided to take the advice. But I was still a frustrated traveler.”

Although he’d been born in Iowa, the eastern part of the United States was a really distant place to John Wayne and he always had wanted to go there. But they weren’t passing out railroad tickets on street corners, so Wayne stayed west. He made his first trip shortly after he met John Ford. It held little significance at the time, but just this year he thought of it again. They had gone to Annapolis, Maryland, and Wayne had played a small part—as a midshipman—in a service picture. Director Ford stood behind the camera and eyed the young actor not too pleasantly. But after the shot was taken to his satisfaction, he drew Wayne aside.

“Young man,” he said, “you’re probably the worst actor in the world. But I have a feeling that someday we’ll do something together that will make you a star.”

That was really the beginning of a relationship between a star and director that has become a Hollywood legend.

In the summer of 1954, John Ford was to make a picture called The Long Gray Line. He is meticulous in his choice of actors, often spending weeks searching for just the right player for even a minor part. One day he called Wayne.

“Duke,” he said, “I took you to Annapolis to play a midshipman more than twenty years ago because I thought you were the right guy for the part. Now I want to ask a favor. There’s a small part in this thing I’m doing now that I haven’t been able to find the right guy for, but I just saw the face of the lad I want. It’s your boy, Pat. Let me take him along.”

Pat, all six feet of him, and only fourteen, went. His dad was so pleased that he flew east and drove to West Point and stood behind the camera with Ford and watched his son step into his own footsteps.

Some of the more amusing anecdotes in the life and travels of John Wayne have toe do with the publicity jaunts he has been obliged to make.

Shortly after he was signed by Fox Films and starred in an epic western called The Big Trail, Wayne was informed they were going to change his name from Duke Morrisson to John Wayne. He didn’t like the idea much, but he had little choice. And then he was told that he was leaving immediately for a tour of the east, in order to familiarize the country with Fox’s new star. Duke and a publicity man boarded a train and had an uneventful ride to within fifty miles of Manhattan. Then the press agent opened a suitcase and took out an outlandish costume and told Wayne to put it on.

Wayne took a look at the get-up and said he wouldn’t even wear it in a movie.

The suit was buckskin, with plenty of shredded fringe on it. The shirt was the loudest thing Wayne had seen that didn’t explode and there was an improvement on a ten-gallon hat. Duke shuddered and refused to get into the clothes.

“Look, Bud,” said the press agent, “you’re supposed to be a gunfighter, a frontiersman. Now get into the suit.”

“But I’ll look like an idiot,” said Duke.

“You just get into the suit,” said the press agent, “and leave all the thinking to us. And remember your name is John Wayne.”

Fresh from the days of dining in hamburger joints, Wayne got the message.

“Yes, sir,” he said.

It was a sight to behold in New York and Philadelphia. Wayne was attempting to hide behind pillars and in doorways as he was led about for display by the press agent. But the payoff came in Chicago. Wayne was at a press conference and fed up to the neckline of his loud shirt.

“Do you always dress this way, Mr. Wayne?” a reporter asked.

Wayne turned his back on his keeper (who was nodding his head vigorously) and almost snarled an answer.

“What do you think I am? A monkey?” he roared. “I not only don’t always wear this outfit, I’m never going to wear it again!”

And he stalked into the bathroom where he began to tear off the clothes and fling them into the other room in the center of the group of reporters. He has never worn Western clothes off screen again.

There were rough years after that, but John Wayne never would go on a publicity tour unless he was well briefed in what was expected of him. He wanted honesty in his contact with the public, and honesty from his producers.

A few years ago, though, he fell into a well-laid trap. Herbert Yates, the head of Republic Studio, called him on the phone and said he was going to London to chat with some of his representatives there. He casually suggested that Wayne come along. Duke wasn’t working, so he agreed.

In London, after checking into their hotel, Wayne happened to look into a closet he hadn’t used and saw a large Stetson hat perched on a shelf. He called in one of Yates’ assistants and demanded to know what it was doing in there.

“Well,” said the assistant, “the boss wants you to drop in on a few theatre managers with him and we thought it might be nice if you were in character.”

“I am in character now,” said Wayne, pointing to the plain snap-brim he had tossed on a chair.

But for once he was disuaded. He agreed to wear the hat. The next morning a small group of Republic people piled into a car and set out to see the theatre managers. As they pulled up to the first theatre, Wayne thought there was considerable activity around the place. They went inside to the manager’s office and chatted a few minutes. Then came the shaft.

“Duke,” said the man who had dug up the Stetson, “there are about three thousand kids sitting out there in the theatre waiting to see a morning show. It might be nice if you just stepped out on the stage and say hello.”

“Now cut it out,” said Wayne. “I came over here on a pleasure trip. Not to make personal appearances.”

“I know,” said the fellow, “but those kids know you’re here and it would be a pity if they didn’t get just a peek at you.”

“Okay,” said Wayne, “but this whole thing looks like a set-up to me.”

“How can you say such things?” asked the man, pushing Wayne toward the wings. Then, just as Wayne was about to step on the stage, the chap waved his hand and the Stetson miraculously appeared on Duke’s head.

Although he was inwardly fuming, Wayne spoke to the kids for about ten minutes and then started to take his leave. The manager stepped forward.

“Children,” he said, “don’t you think we ought to sing our song for Mr. Wayne?”

There was a roar of approval, and while Duke stood in complete embarrassment, every kid in the theatre stood up and they sang “She Wore A Yellow Ribbon.”

When it was over Duke thanked them and then charged into the office. He poked his finger into the innocent face of the man with the Stetson.

“You might be able to tell me,” he said, “that it was just a coincidence that those boys and girls were in this theatre when we came in. But nobody is going to tell me that three thousand English kids all know the words to ‘She Wore A Yellow Ribbon’ when the picture hasn’t been opened here yet! I’ve been framed!”

He made the rest of the tour as planned, visiting some twenty London theatres that day—and in each one the kids stood up and sang “She Wore A Yellow Ribbon.”

“I was sore,” Wayne said. “But I couldn’t get too mad at a guy who taught half the kids of London to sing a song just for me.”

If you saw The Quiet Man you probably remember the scene in the small town pub in which the citizens, looking upon the stranger among them as something of an upstart, refused to have anything to do with him. Well, that scene came from real life. There was little to do in the village in which the picture was being shot, so the second evening the troupe was in town, Wayne wandered down to a local pub and set his foot on the bar rail. The place was well filled with Irishmen—and they quieted down in their conversation when Duke came in and eyed him suspiciously. Nobody recognized him.

Wayne had a drink, then offered to buy one for the barkeep. The man, with a nose as red as a tulip, avowed he never touched the stuff. After a while Wayne tried again. He asked the man standing next to him if he’d join him. The fellow muttered something about being a teetotaler. Wayne stood at the bar and fumed. Finally, he addressed the bartender in a loud voice.

“Set up a drink,” he said, “for everybody in the house.”

The bartender did so and Wayne raised his glass. “Ireland forever!” he said, and downed his drink.

There was a long pause; nobody touched an alien glass. But here was a toast few men could ignore. And what Irishman will waste whisky? Finally, one chap picked up his shot and raised it high. One by one the others silently followed suit until all the glasses were empty. Still not a word had been spoken. Wayne was just about to give it up when a small fellow down at the end of the bar raised his voice.

“Bartender,” he said, “I wish to buy everybody in the house a drink—so that we can toast our friend from America.”

Wayne was no more a stranger.

These were pleasant journeys, even though there were minor annoyances and hard work involved in many of them. But there were unpleasant trips.

About the time his marriage to Chata Wayne was headed for a reef, John Wayne spent no more time in America than he had to. Duke used to take off and go anywhere an airplane would land. And they landed in some unlikely places. Small airfields in the Andes. Remote military establishments, for Duke never missed an opportunity to drop in at some outpost to say hello and chat with Marines in the field.

He toured every South American country and, as usual, played fair with the press. Some of the journalistic methods of our South American friends were quite shocking to him, though. There was the time he had just fallen asleep in the nude on top of his bed in a city in Brazil when he was awakened by a bright light. He snapped open his eyes and saw a photographer just lowering his camera at the foot of his bed. The light had been a flash bulb. The cameraman took off like a deer and Wayne, with a mighty roar, leaped out of bed and chased after him. He caught the terrified photographer at the door and dragged him back into the room.

Although Wayne doesn’t speak Spanish, the man knew what was expected of him. He withdrew the plate from the camera and handed it to Duke.

“Now,” said Wayne, “if you’ll just sit there and wait until I get dressed I’ll pose for all the pictures you want. But there’ll be no cheesecake, see!”

Wayne got dressed and they took pictures for an hour.

It was on one of these exile trips that John Wayne first met the girl who is to be his wife, Pilar Pallette. It was in Lima, the capital of Peru, where she was employed as an actress. He saw her across a room full of people and paid little attention to her. Somebody introduced them, but neither stayed to chat. It was not love at first sight. They found nothing in common, even though both were unhappy because of marriages that were on the rocks.

But he met her again in Los Angeles a year or more later, and, as time has proven, they meant a good deal to each other after that meeting.

The sun was beginning to slip behind the row of elm trees across the valley. The large green gate began to swing open in response to a button pressed by Scotty in the kitchen. A car pulled on to the macadam road and threaded through the shrubs and trees toward the house.

Duke got up and walked to the parking strip and helped the small Peruvian girl out of her car. He kissed her lightly on the cheek and led her to the terrace.

“Scotty,” he called, “you can serve dinner out here any time you’re ready.”

“Yes, sir,” Scotty called back.

Wayne turned to Pilar. “I don’t know how you feel about eating outdoors,” he said. “But you might as well get used to it. You and I are going to be eating dinner out here for a long time. This is going to be home.”

They smiled at each other—and you could tell they both had been looking forward to the day the big man finally came home to stay.

THE END

—BY JIM HENAGHAN

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1954