James Dean’s Happiest Moments

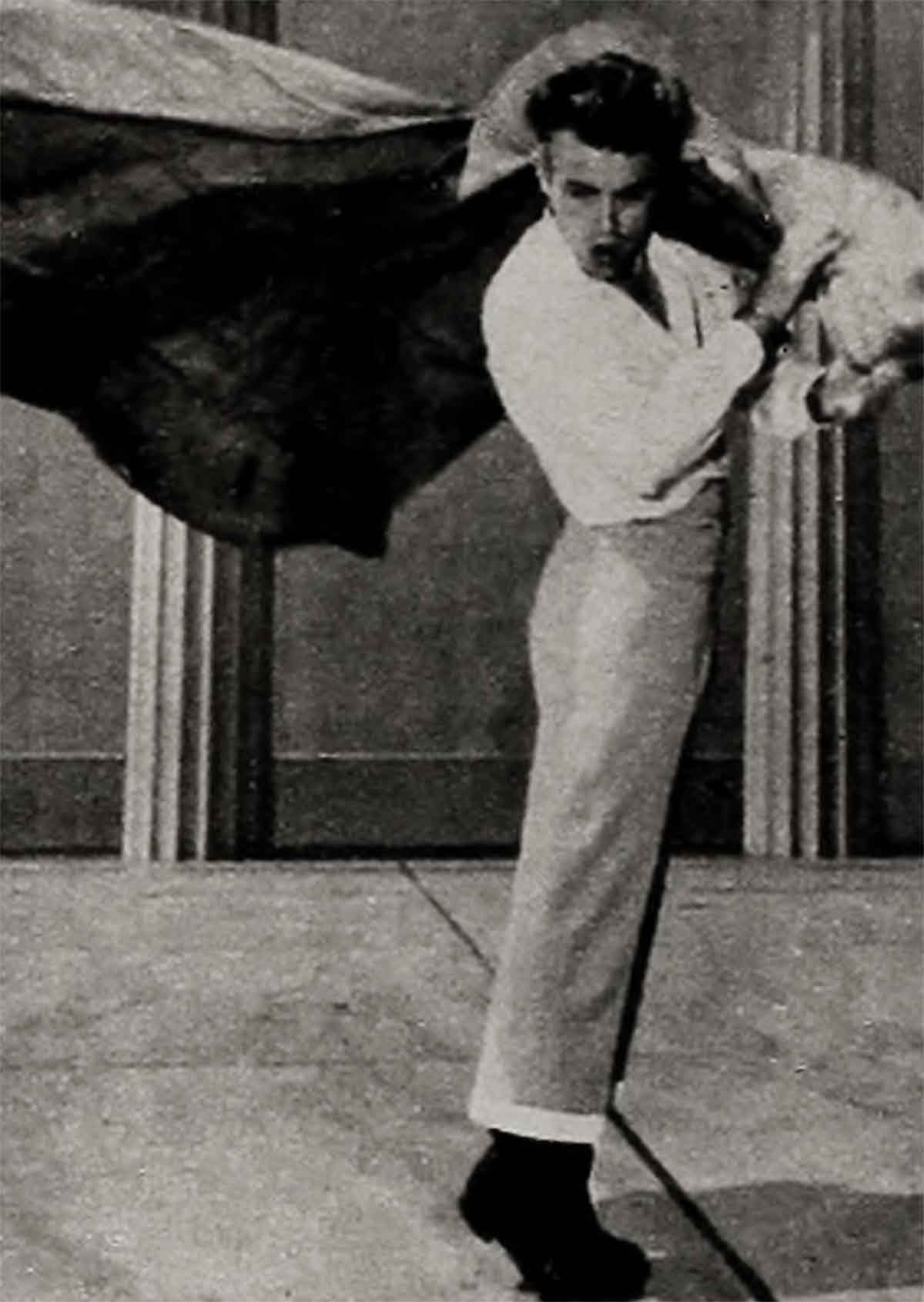

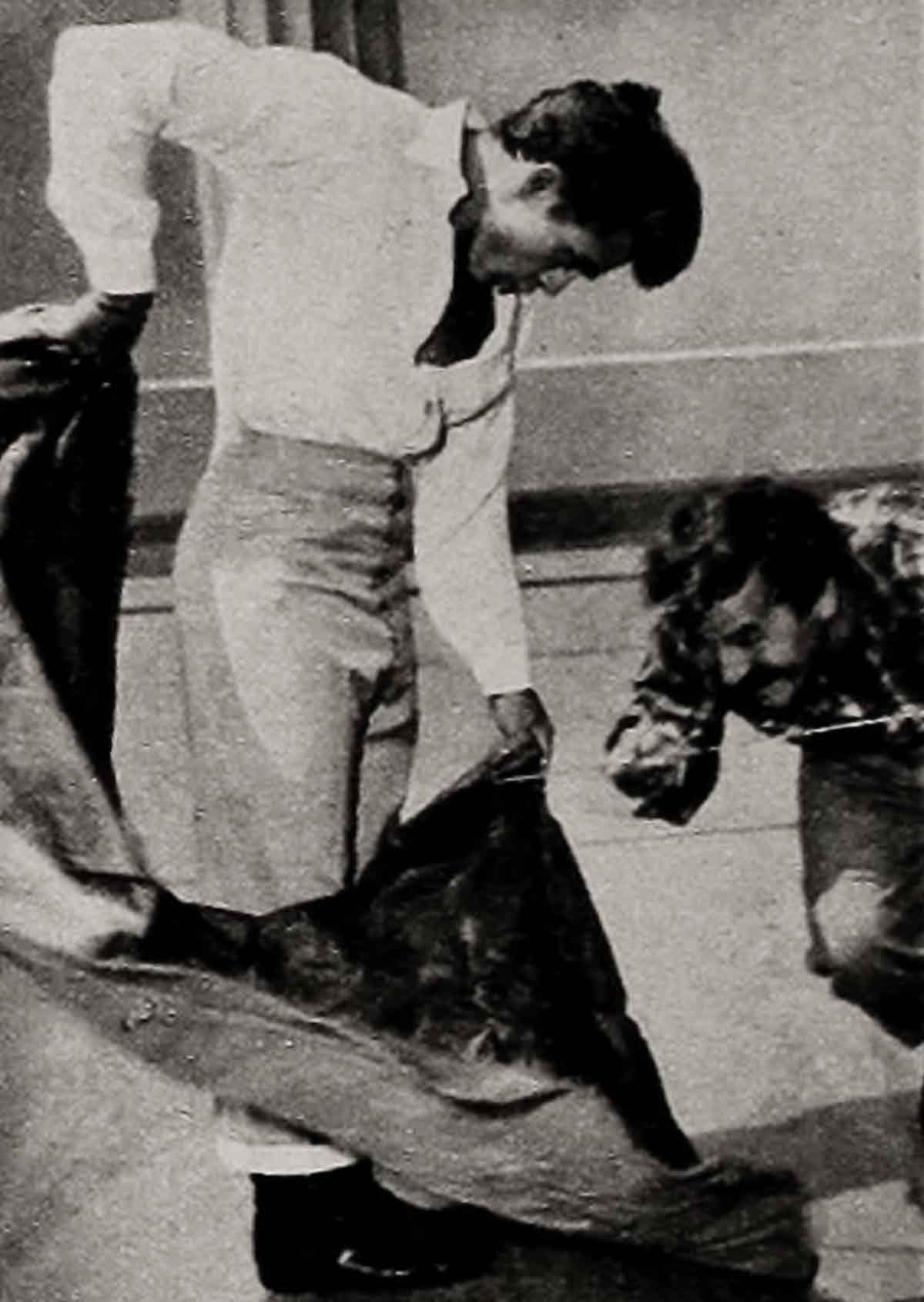

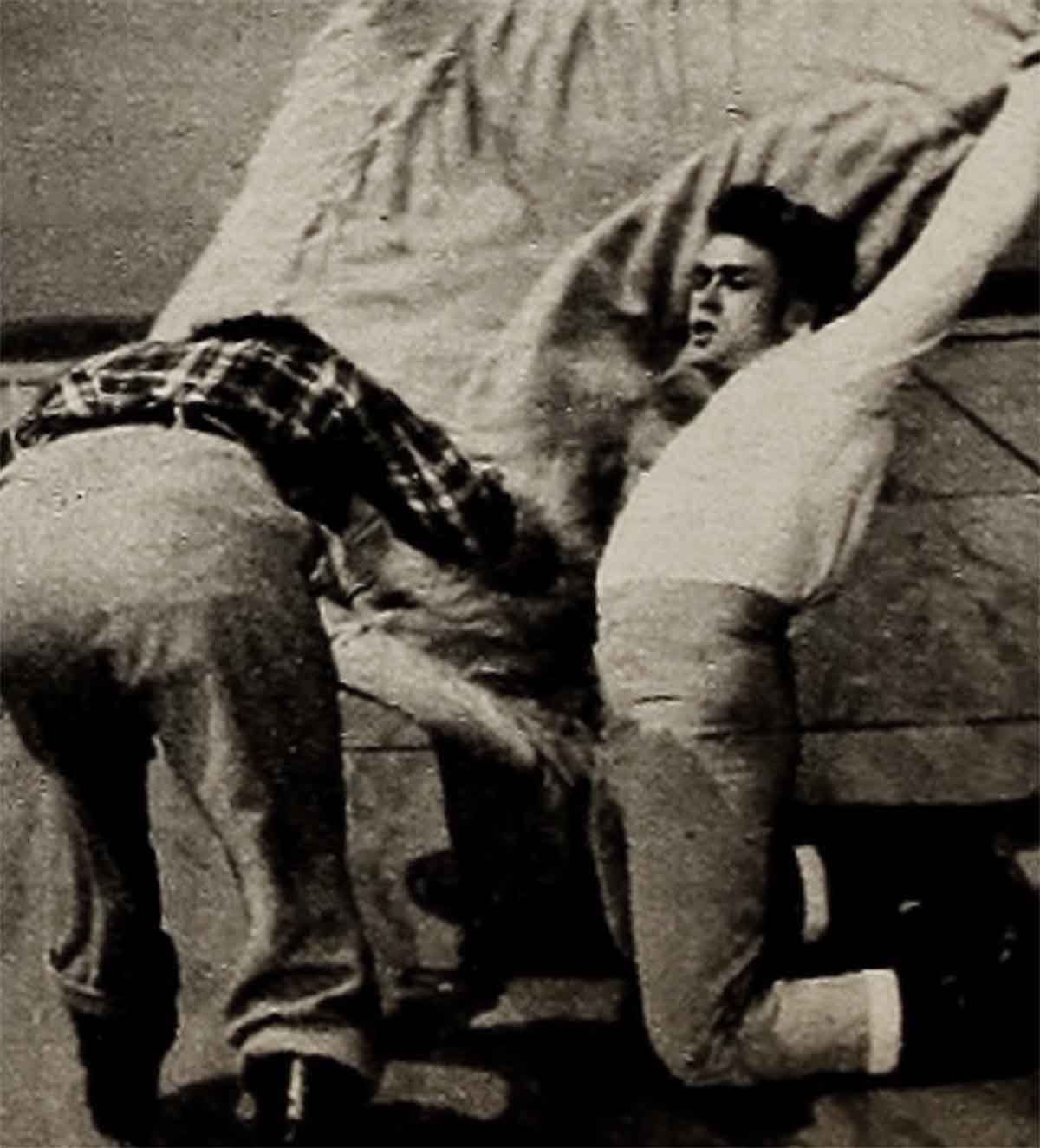

I wish someone would explain human beings some day. Why is it that whenever I think of Jimmy Dean, who loved the fun of life much more than he loved life itself, I feel like crying? I mean, the first guy to hoot at me, if he saw me, would be Jimmy himself. I remember his reaction one afternoon when we worked in Rebel Without A Cause, and we all argued against his decision to use a real knife, instead of a prop, in the famous knife fight scene. All we had to do was catch the look in his eyes as he stared in protest at us, to know that a prop would be too dull, let alone unrealistic, as far as he was concerned.

So he might get cut. So what?

So he did get cut—and he was delighted with the feeling of satisfaction that came to him, a feeling based not only on the fact that he had lived his role more than he had pretended it, but that there was a kick to this way of acting, as there should be to everything a fellow pitches in to do—and no matter the cost.

I think my sadness comes because nobody seems to have remembered this Jimmy Dean—or talks about this Jimmy Dean, the fun-loving Dean.

The Jimmy Dean I knew was intelligent enough to know that the truth in life comes out in its laughter, and so he lived mostly in laughter when he was with his friends (and, as I later found out, when he was with favorite members of his family). It was true that he could be introspective. But this was a passing thing with him. He was always curious about his acting ability, wondering if it was something he had inherited, and he couldn’t keep from making investigations along that line.

Also he could be touched deeply by sentimentality, since he was only ten when his mother died and her going was a shocking loss in his life that he never fully got over. One day he told me that at his mother’s death he managed to undo the ribbon which was wrapped around the funeral door wreath, and slept with it under his pillow for nights afterwards.

But these things didn’t always plague him, and the everyday Jimmy was mostly a happy Jimmy. My favorite memory of him goes back to a night when I was sitting at the Villa Capri restaurant in Hollywood with some friends and he entered wearing a leather jacket, tight whipcord britches, gauntlets, high boots, and dangling a pair of goggles from his hand.

“Hey, man,” he greeted us. “My new motorcycle is outside. Real sharp. Come out and see me take off!”

This was good! We tumbled out of our chairs and followed him. He led the way toward the door and out onto the sidewalk—where there was no motorcycle at all in sight. Not for us, that is. But for him there was. “Ain’t she a beauty?” he crowed, pointing at nothing.

Then he went over to the curb, swung his leg over a completely imaginary cycle, blew his lips out so they vibrated with the blast of an accelerated motor, and then went shuffling down the middle of Sunset Boulevard, leaving us behind, staring like a pack of fools.

Jimmy, as everyone knows, really did ride a motorcycle around Hollywood for a while, but I would like to clear up the talk that he got one because he was trying to duplicate every move made by Marlon Brando. Jimmy first became a motorcycle bug while he was still attending Fairmount High School back in Indiana, eight years before his death. His best friend there, Bob Middleton, who was a classmate of his, told me this when I went to Fairmount for Jimmy’s funeral.

“Jimmy never imitated anyone,” Bob said. “He was always having too good a time being himself.”

We both did impersonations

This is true. I have other proof of it. Both Jimmy and I could do impersonations of Brando, as well as of Montgomery Clift and a lot of other well-known stars. However, we did this as exercises, and for fun and also as technical training in our profession, you might say. But one day a chance came to cash in on these take-offs. And it came to Jimmy not long after he had made his hit in East of Eden. An agent who signs attractions for the Las Vegas hotels talked of a contract in terms of tens of thousands of dollars if Jimmy would make up an act. And the story of the offer was immediately printed in the trade papers.

“What are you going to do?” I asked him the next day in a lunchroom.

“It’s a lot of money,” he said, grinning. “And not much work. After all, how long has it been since we had to share a hamburger to keep from starving?”

“You mean you’ll accept?”

He shook his head against the idea. “No chance,” he replied. “This is all it would take to classify me as just an impersonator. I’m out to be an actor.”

“Good,” I told him. “Tell the agent there is no chance of ever getting you down to Las Vegas.”

“No, that isn’t so,” Jimmy replied. “When I have done a few more films and I am better established as myself, then I can do all the impersonations I want and keep my own identity. But until I am Jimmy Dean publicly, I’ll never be anyone else publicly.”

So he laughed off maybe $25,000 or more, got up from his chair and went over to a flower box near the window over which he fiddled around with both hands. Then he turned around and asked me if I was ready to leave.

“What were you doing with the flowers?” I asked as we paid our checks.

He had to giggle. “When I was home in Indiana not long ago I picked up some wheat seeds,” he said. “I just planted some in that box. Can you imagine their surprise when they get a strand of wheat?”

He was someone by himself

No, a fellow like Jimmy Dean didn’t have to follow in anyone else’s footsteps; not Brando’s, not Clift’s. A fellow like Jimmy was someone all by himself. The first time we ever got together socially, after we had been introduced to each other at a television studio where we had signed to make a Pepsi-Cola commercial, he established himself as a warm-hearted boy with a witty way of looking at things.

Maybe I should have put the word socially in quotes, because Jimmy paid me a visit, and where he found me “at home” was in a sort of sewer extension I happened to be living in at that time. In return for taking out the garbage in an ancient Hollywood Boulevard household, and doing a few other odd jobs of similar stature, I was permitted to live in a damp basement alcove that was just wide enough for a bed and high enough to let me creep into it.

Jimmy took one look around and then grinned at me. “You won’t need a coffin when you die,” he chuckled. “Just put handles on this room.”

I started to apologize. “I’m sorry, but this is the best I can do . . .”

He waved a hand to make me stop. “Aw, this looks like a penthouse compared to my underground rathole,” he said.

Jimmy’s tough times

The fact is, of course, that Jimmy too had his tough times. Early in his New York days, when he was picking up an occasional television job, he showed up at a rehearsal one morning in bare feet. Immediately everyone figured he was trying to be a character and attract attention. But that wasn’t the reason at all. The night before he had been caught in a heavy rain and his one pair of shoes—very cheap shoes—had gotten soaking wet. By morning they had shrunk at least three sizes. Jimmy had tried shoving his feet into them until the tears came, but it was no use. Finally, in desperation because he couldn’t afford to lose the job, he went barefooted.

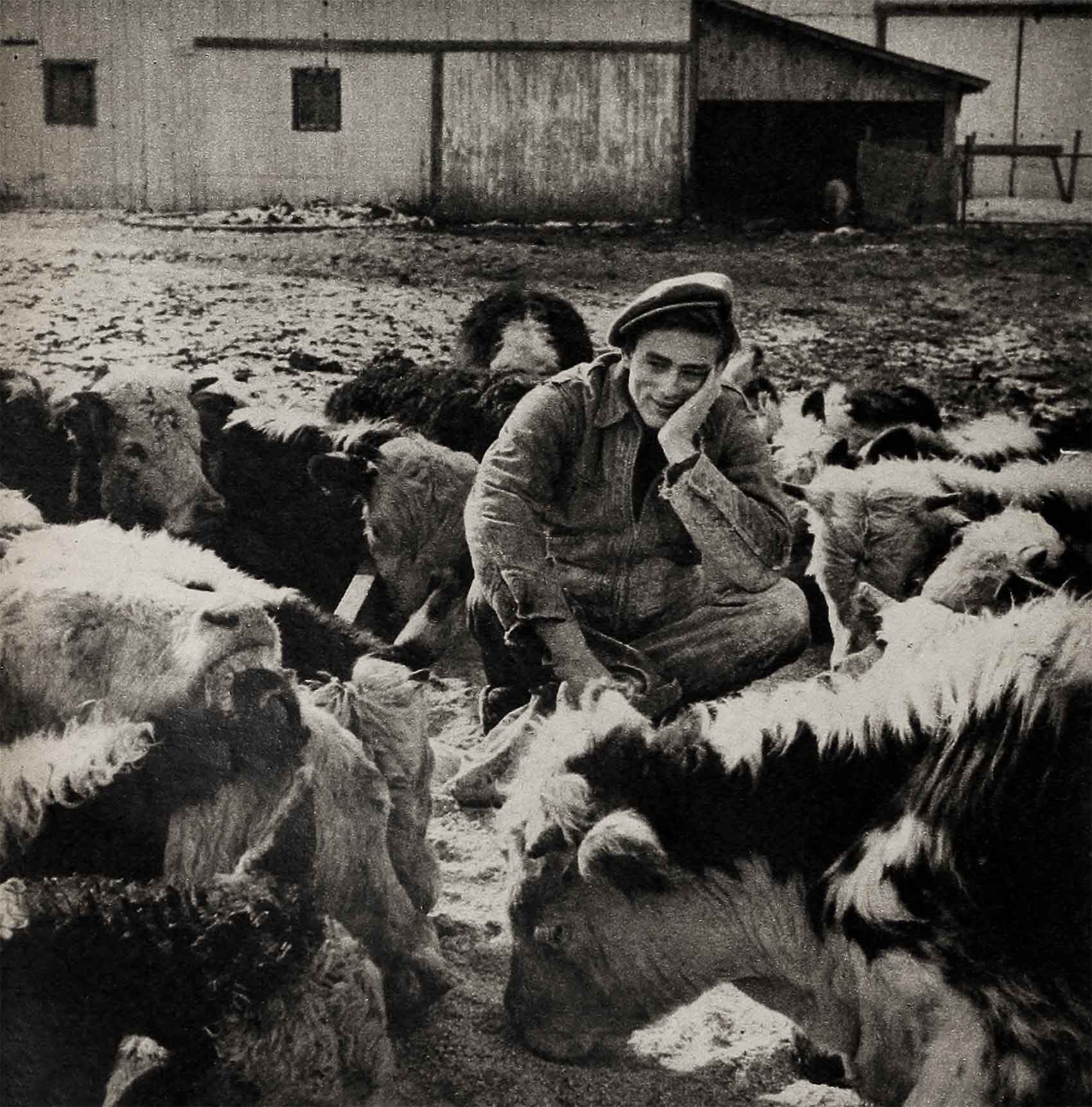

I don’t know whether Jimmy ever starved in New York. He wouldn’t dramatize too much about himself. But I do know that he must have had some pretty meager meals for long periods there, because one day in Manhattan he got to dreaming about how well he used to eat on his Uncle Mark’s farm, back in Fairmount.

“You know what I did?” he’d say to me. “I just upped and took off back home for Indiana. But I didn’t go alone. I had met a couple of kids, a boy and a girl, trying to get into show work, who, I knew had been living on about twenty-five cents a day. I took them with me—what the heck, we all hitchhiked—to let my Aunt Hortense fatten them up. And boy, she did. And boy, how they loved her treatment!”

There was a short period when Jimmy and I were together in New York. This was when I was in the Navy, stationed at New London, Connecticut, and coming into New York for my leaves, and he was trying to get into a good play at the same time. A good many of our meals those days consisted of hot dogs and orange juice which we got at the Nedicks’ counters around Manhattan. But we didn’t call them Nedicks’. We would say, “Let’s dine at the Orange Room tonight.”

A vivid personality

I knew Jimmy for five years; from the day we met in the Jerry Fairbanks Studios in January of 1951 to make that TV commercial, to the fall of 1955, right after he finished Giant, just before the highway accident at Paso Robles, California, which was his curtain. But in that five year period I did a Navy hitch of almost three years. Yet so vivid was his personality, and so eager his appetite for life, that it always seems to me we crowded ten years of fun into those two years we hung around together. At least my mind teems with the things we did . . .

The time, during the filming of Rebel when he suddenly jumped to a balcony, in the middle of a scene, and began spouting Mark Antony’s speech from Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, and then threw me an eye as my cue to come play the “crowd” for him . . .

The day we entered the commissary at Warner Brothers and he saw his picture on the wall with all the studio’s stars; he tore it down, muttering, “What do they want to do? Kill everyone’s appetite?”

The afternoon he ran his car, the same Porsche in which he was killed, around the Warner’s studio lot while seated on the wrong side of the seat, so that no one was behind the wheel and people thought an invisible man was doing the driving . . .

The day I visited the Giant set wearing a gay Mexican peon shirt that John Wayne had given me, and carrying another that I gave to Jimmy. He flipped, and just like a kid, had to take his costume off right there, in front of a hundred technicians, to try on the shirt . . .

The time he “fooled” me during the filming of the Planetarium scenes in Rebel. I was supposed to point down the hall of the huge building and cry, “Here he comes now.” But when I did Jimmy showed up at the opposite end of the hall—which meant he had run about a quarter of a mile around the outside of the building just for the laugh he’d get in making a completely wild entrance . . .

I know a lot of this sounds like kid stuff; but he was a kid—all heart, some stomach, not too much sense yet and a lot of talent. He had a quick eye for girls but he was at an age when his imagination was fired by the great work he might be able to do, not the romances he could fall into. He could laugh and he could fight with Natalie Wood—but always he had a deep respect for her talent, and this is what made them an interesting pair to each other. I was his friend, and this was fine. But if I could come across with a constructive piece of advice for his acting—oh, this was something extra as far as Jimmy was concerned. This really impressed him.

He was always thankful

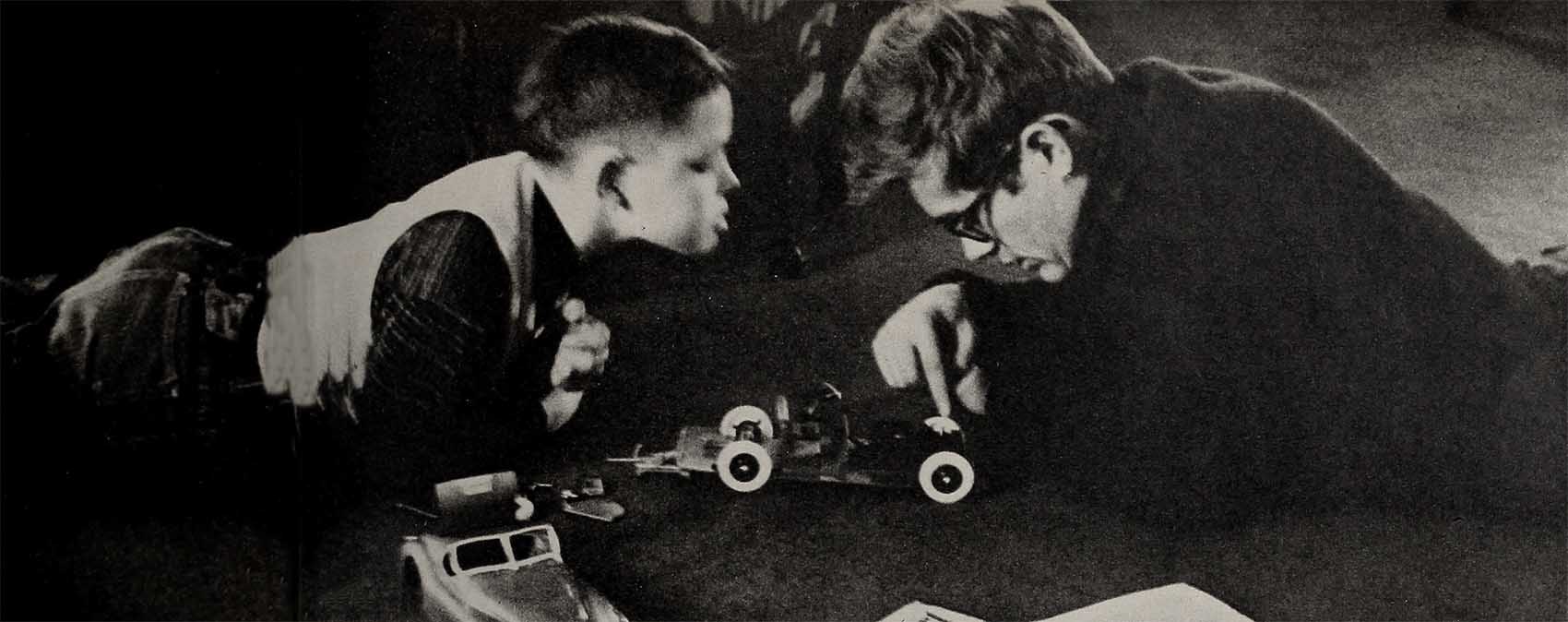

It may be remembered that in the opening scene of Rebel Jimmy is seen fondling a toy monkey. I made a helpful suggestion or two about this bit of business—nothing very important. But Jimmy never forgot it. He was always thankful.

There have been stories that Jimmy was self-centered. People who think this had no real knowledge of him at all. I can think of any number of instances to prove the contrary—besides the ones I have already given.

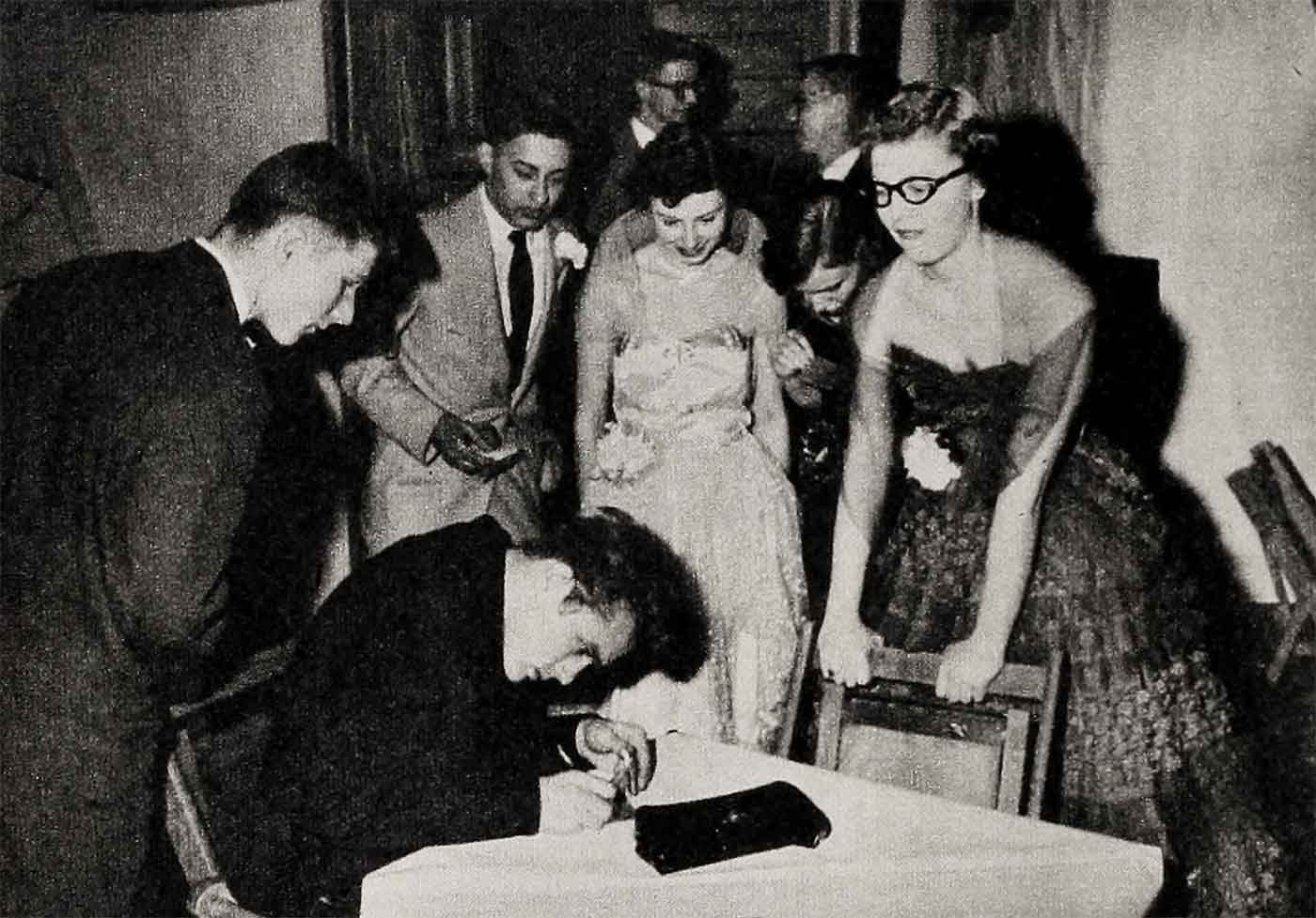

When I joined the Navy I had gotten nowhere as an actor yet, and it was while I was away on sea duty that Jimmy got his break in East Of Eden. Then when I got a start in Mr. Roberts, Jimmy was away from Hollywood and I didn’t run across him until after the picture was finished. One day, at Warners, there we were—both standing in front of each other, after three years. It was like two brothers meeting after a lifetime apart.

He told me that he had caught a screening of Mr. Roberts and that he thought I was great in it and that I had nothing to worry about. I told him I had seen East Of Eden and that it would be silly for me to say that he was a hit in it because everybody knew it—but I went ahead and said so anyway.

It was towards evening, about 6:30 o’clock, when we started talking, and we slowly walked out towards the parking lot where our cars were—talking all the way. When we got to Jimmy’s car we had a little more to say, so we stood there continuing our talking. And then when we had said that bit it reminded us of more, so we kept on. And it went on like this until, so help me, it was nearly 10 o’clock before we finally could break it up and part. We had gabbed away for better than three hours.

This should furnish an idea of the vitality and depth of Jimmy’s friendship, and how strongly his nature was to give . . . not to take.

The instinct to act

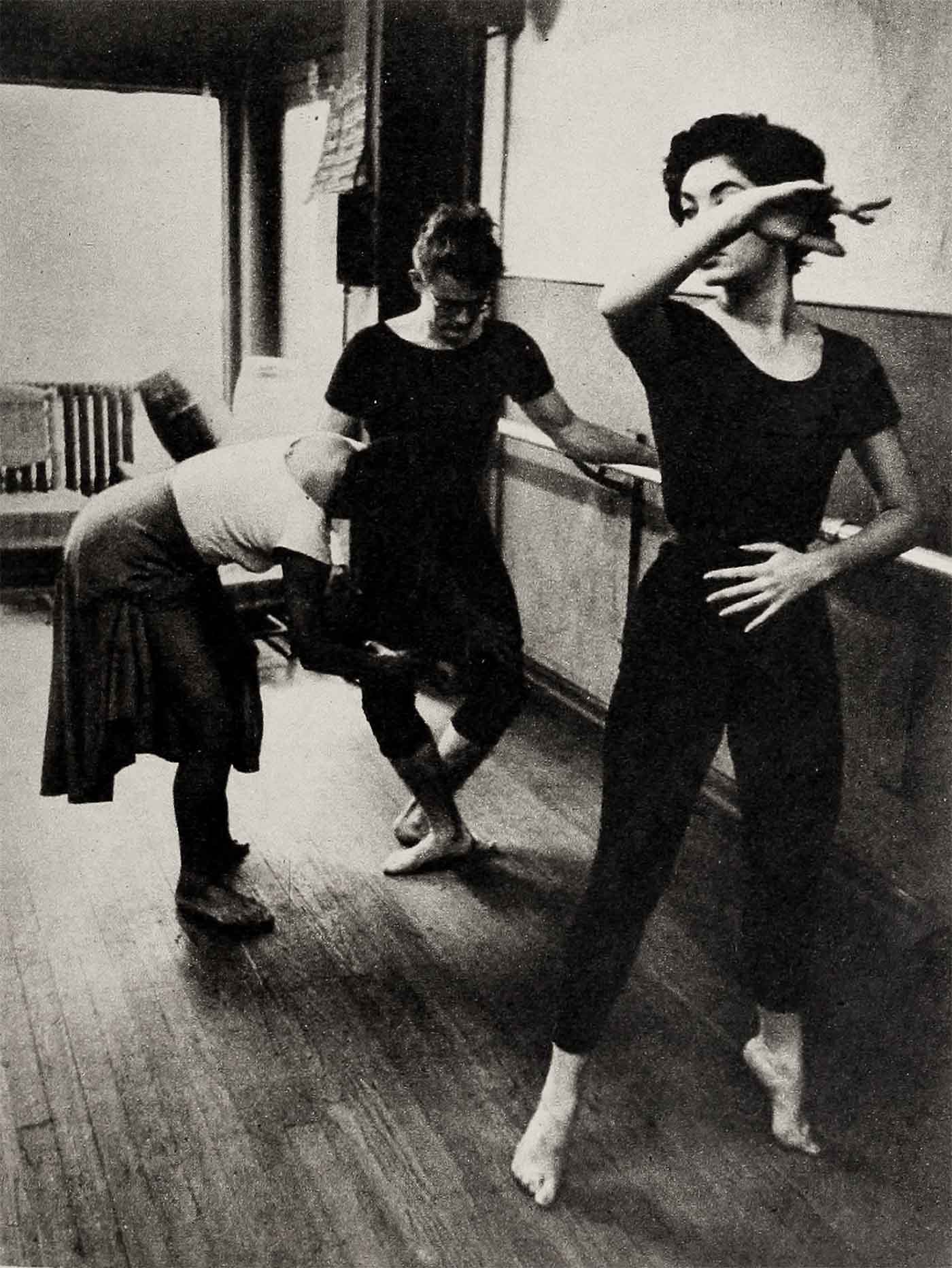

There remains one more side to Jimmy that might be illustrated; his wonder about himself and the instinct to act. I remember, soon after we first became friends, that he called me on the phone once about 3 o’clock in the morning.

“What are you doing?” he asked, and then giggled because it was such a silly question to ask in the middle of the night.

“Nothing,” I said.

“Come on over and let’s shoot the breeze,” he begged.

He was in a talkative mood, I found, when I came over, and he went into everything. But his mind always came back to the same subject—what makes a fellow want to be this or that?

“Were there ever any actors in your family?” he asked.

“No, I’m the son of a coal miner,” I said.

He shook his head, puzzled. “And my folks were all farmers,” he commented.

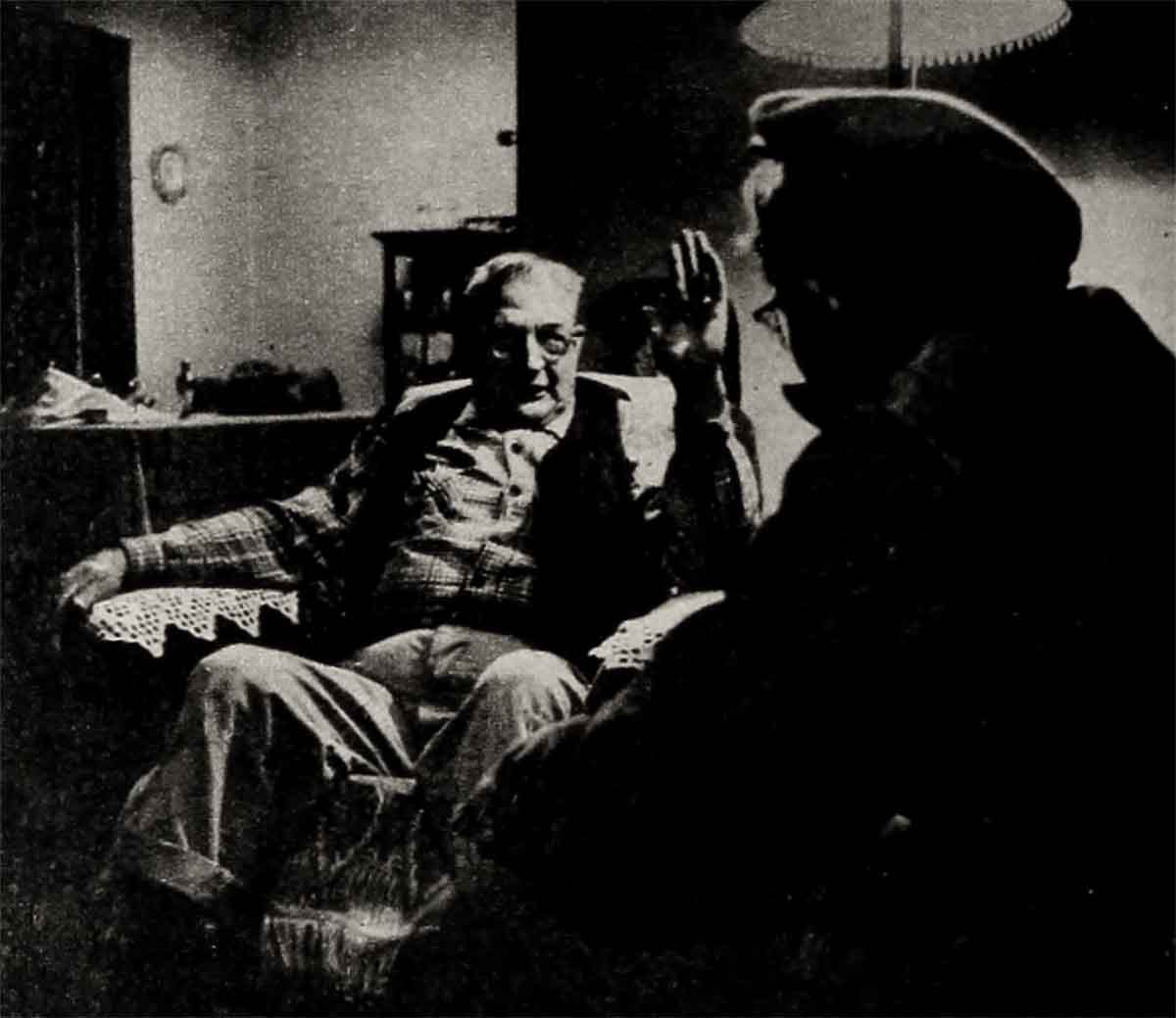

For his twenty-fourth (and last) birthday, February 8 of last year (1955), he went home to his Uncle Mark Winslow’s farm near Fairmount, Indiana, where he had been raised, and stayed a week or so. One night there was a whole family gathering including his seventy-five-year-old grandfather, Charlie Dean. Jimmy started pumping his grandfather on his favorite subject again; were there any Deans who were artists of any kind, if not actors? And Grandpa Charlie recalled that there was a great-granddaddy “Cal” Dean, who had been an auctioneer.

Cal, said Grandpa Charlie, could get up in front of a crowd and entertain them royally as he disposed of the various articles he was auctioneering. Jimmy was delighted, and then tickled even more when his grandfather recalled that either Cal or one of his brothers had written a

two-line verse about themselves. The other brothers were named John, Harry, Pat, Joe Bennel and Kil (for Achilles). The poem went:

“Joe Bennel Kil Cal, while a Pat and John,

Stood off and looked on.”

Now Jimmy was enjoying Peas There actually had been a poet in the family.

A similarity

“Say, Grandpa,” he said. “In the picture I made, East Of Eden the name of the character I play is Cal!”

And then for some reason, Jimmy asked when Cal, his great-granddaddy, had died.

“In 1918,” Grandfather Charlie replied.

“That’s funny,” said Jimmy. “The time of East Of Eden is the period of 1918.”

When Jimmy came back to Hollywood I told him he ought to take better care of himself: that he ought to get more sleep. Jimmy was the kind of fellow who counted sleep a terrible waste of time. He was always giving me that old business about how the hours of sleep add up.

“Do you realize,’ he would say, “that if you sleep eight hours a day you have slept for twenty-five years of your life by the time you get to be seventy-five? And that means you have been dead for twenty-five years. Because whats the difference? When you are asleep you are practically dead.”

Maybe that’s why I could cry about a kid who was always laughing himself. He loved life too much not to have had at least his full share of it.

THE END

James Dean will soon appear in George Stevens’ Warner. Bros. Giant

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1956