Knee-Deep In Stardust

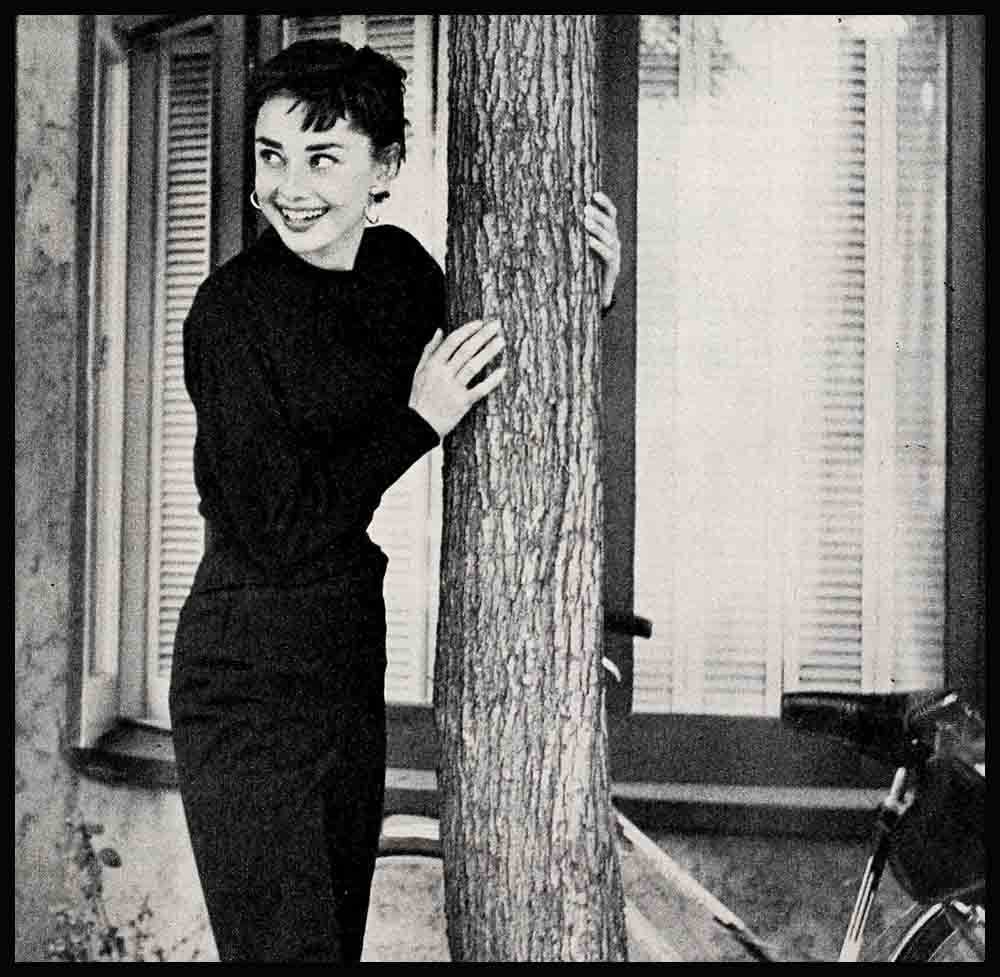

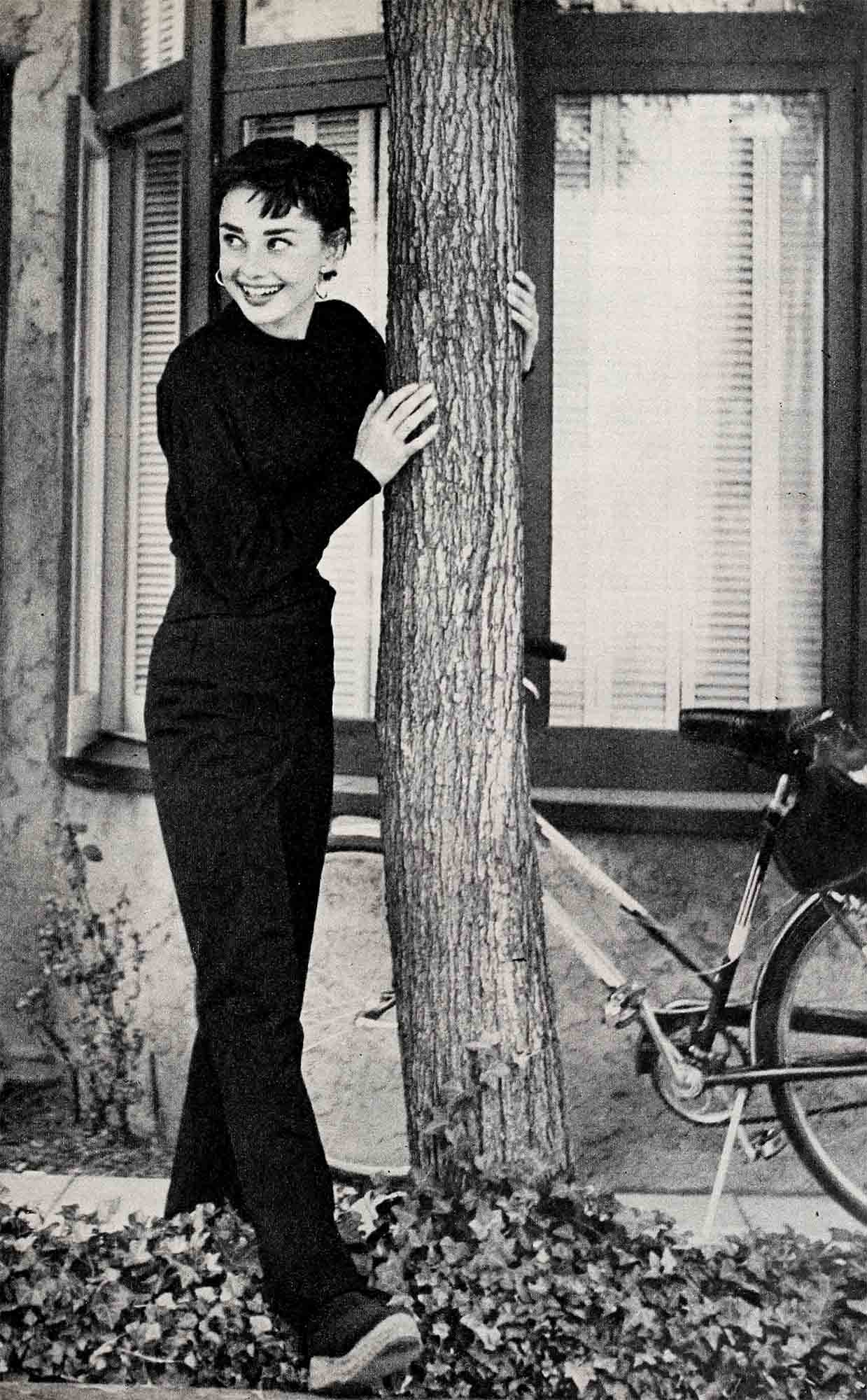

Any one of the thousands who went to see “Roman Holiday” because of Gregory Peck and came reeling out an hour and a half later muttering “Who is that girl?” will vouch for this statement:

Seeing Audrey Hepburn is a vitalizing experience.

Meeting her, sharing a pot of tea with her in her rather ordinary little Paramount dressing room, is better than a shot of adrenalin.

The girl is so alive, every sense so aware, that not even the worst cynic could come away after an hour with her without smelling spring in the air, hearing faraway music from the heaven

She thinks life is wonderful. She doesn’t want to miss a minute of it. And this is her magic. It’s the clue for any girl who would like just a little of the excitement, just a few of the plaudits which have been Audrey Hepburn’s recent lot, and who—like Audrey, let it be emphasized—are short one or two of the made-in-Hollywood musts for success.

Audrey is not a classic beauty. (Although those shaggy-lashed dark brown eyes shining out of her mobile, heart-shaped face can make the most critical forget it.) For modelling, which she did at one time for a fast fifteen dollars a week, her figure would be an asset. But the films, traditionally, have required more voluptuous contours. She is string-bean-like by Hollywood’s standards, too tall, too thin, and virtually, as she herself candidly admits, flat-chested. And she will have no truck with “falsies” either.

But if sex is the life force, then, by anybody’s standards, this girl is loaded with sex, for there never has been a girl so loaded with pure vie. She seems to get almost physical pleasure out of just plain breathing. The simplest things—things too many of us take for granted—things like food, and sleep, a new record, or a small present, give her a lift and a bounce. And the lift and the bounce are contagious.

Lithe-legged on her fancy chrome-and-aluminum bicycle, a present from Director Billy Wilder, her mentor in “Sabrina Fair,” she wheels erratically about the Paramount lot.

“Hi, Ray, how are you?” “I say there, Jess, isn’t it a beautiful day?” And the stern faces of these studio police officers light up like searchlights.

The mail boy comes in with a stack of fan letters, a routine job. But there’s nothing routine about his reaction to Audrey. “Why, Miss Hepburn,” his face lights up too. “Didn’t know you were back. We missed you.”

Audrey has had all of one day off from her jam-packed “Sabrina Fair” schedule. But she responds to the welcome. “It’s wonderful to be back, Billy,” she says, and Billy goes his way whistling.

“It is good to get away,” Audrey says after he is gone. “Just for the fun of coming back, with people saying ‘hello,’ and ‘how well you look.’ ”

Herman, the waiter from the little restaurant across the street, who has been rolling trays to stars’ dressing rooms for so many years that he should be wearing a captain’s stripes, blushes and almost spills the tea in the presence of the first star he’s asked for an autograph.

“Tea, Herman,” Audrey says. “How fine. Now we will be warm and friendly.” For Herman, it’s better than a tip.

The tea is just tea, compounded of tea bags, and water lukewarm from its journey. But Audrey’s appreciation gives it flavor, and the atmosphere suddenly is fine, and warm and friendly. And the cookies are Dutch. . . . “From home,” and delicious. And Audrey, savouring every bite, eats two of them. Four. Six.

It is fortunate, it seems imperative to comment, that Miss Hepburn has no calorie-counting problem. Since she so obviously loves sweets, it’s lucky that she can have all she wants.

“Oh, but I can’t,” she says, “not by any means. I’m glad I like sweet things—I expect I’d be tubercular if I didn’t. But if I ate all I wanted, I’d break out. It just wouldn’t do. But I’m getting better. Now if I get a box of good chocolates, it will last awhile, maybe for two hours. I used to eat them all without stopping until every last one was gone.”

She used to, she means, when food—unheard of foods like meat and chocolate—were first available at the end of the war.

Audrey lived out five years of war, between the time she was ten and fifteen, in Arnhem, in the Netherlands. And “Arnhem took a bit of everything . . . the bombs, then the occupation, and finally the airborne.”

Just staying alive was an arduous adventure, especially if you were anti-Nazi as Audrey’s socially prominent, economically well-off family were, and if you spoke English and French fluently from your years in English schools.

Ten-year-old Audrey lost the security of her protected childhood brutally fast—as an uncle was shot as a hostage, a favorite cousin executed, her two older half-brothers yanked out of college and shipped off to sweat out the war years in bomb-peppered German labor camps.

“We lost everything, of course—our houses, our possessions, our money. But we didn’t give a hoot. If we got through with our lives, that was the only thing that mattered.”

She doesn’t like to talk too much about it any more, or even to think about it, but those years of terror and privation were crucial in forming the personality as well as the physical person of this stimulating newcomer to the screen.

Her almost childlike enjoyment of little pleasures, her heart-warming gratitude for her recent big breaks come naturally to a girl for whom life itself was for a long time in jeopardy.

Lots of girls Audrey’s age—she’s soon to be twenty-five—live alone in small apartments, cook lonely dinners night after night, and feel intensely sorry for themselves. As for Audrey: “It’s fun to unlock my little gate, and find the new record that the music shop down the street has delivered during the afternoon. I get into old, soft comfy clothes, and then I play the new music while I cook. I love to cook. Steaks. Oh, your American steaks!

“Sometimes, if I don’t have an early call at the studio I invite some friends, and then I really cook. Did you ever steam a whole chicken, young, tender, with just a little water, an onion, a sprig of fresh tarragon? You don’t ever boil it. Just simmer gently, not to break the skin. Strain the broth and chill it. Take all the fat away, every bit. Then reheat the chicken in the broth. First you drink the soup. Then you eat the chicken. Heaven!”

Sleep, to Audrey, is not just something you do to be able to face tomorrow, but another gift from the good God. When she has a day off, she spends most of it sleeping. Of a recent holiday she said, “I slept fourteen hours and then I gave thanks for fourteen hours’ sleep. Life looks so much better to you after fourteen hours’ sleep, don’t you think?”

Audrey can get excited about many things. Nothing is mundane. Clothes:

“For two years I have been working and traveling. London, New York, Rome, San Francisco, Hollywood. I did a play—period clothes; a picture—princess clothes. I have had no time to shop for Audrey clothes. I have two dinner dresses and slacks, and horrible gaps in between.

“But I’ve come to know Edith Head. For a great designer, she’s terribly tolerant of me. She lets me design too. And we have worked out a few little numbers.”

Her work, of course:

“I have only one regret about ‘Sabrina Fair’: it’s finished. Believe me we did have fun. Billy Wilder is the greatest wit. And Bill Holden, Humphrey Bogart are such men! It’s been wonderful.

“And my new play, ‘Ondine’—it’s another French translation, but Medieval this time. It is so good, I think. I work on it every night. And with Alfred Lunt to direct. Who can ask for anything more?”

Audrey was to have two weeks off between the wind-up of “Sabrina Fair” and the start of rehearsals for “Ondine” in New York. All she had to do was pack up, ship her things East, fly to New York, find an apartment and get settled before her mother arrived three days later.

“It is mother’s first trip to America, and I want everything to be perfect. I’ve already ordered tickets for all the new plays, and I’m going to lay it on real thick, New York, that is. I want mother to love it as much as I do.

Audrey’s mother is her “family” now. Her father, whom she has not seen since she was six, is in Ireland, her brothers married and working at careers of their own in the Dutch East Indies.

Mrs. Hepburn made a home for Audrey in London after the war, and worked as an interior decorator while Audrey studied ballet. From dancing roles in musical comedies, Audrey progressed to bits in English films.

When the great French novelist Colette picked Audrey, still practically an unknown, to star as “Gigi” in the American production of her play, and, practically at the same moment, Director William Wyler decided he wanted her for his princess in “Roman Holiday,” and wanted her enough to wait for nine months to get her, “home” became a fluid thing. “Home” was wherever she unpacked her trunks.

New York will be home for the run of Audrey’s new play.

Hollywood, temporarily bereft, will be polishing its best scripts, beckoning with its top directors meanwhile. Because Audrey must come back and soon.

Her kind of love of life is all too rare in our town. Hollywood, having seen Audrey Hepburn, will never let her go.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1954

No Comments