A Very Special Woman

If it’s an unprejudiced story about Irene Dunne that you wish, turn the page. This isn’t it. No one who has known Irene as long and intimately as I have could fail to believe that she is a very special woman.

The other day as Irene and I entered the dining room of one of the big New York hotels, the orchestra, which had been playing “Kokomo, Indiana,” paused for a moment and then played “Alice Blue Gown.”

“Irene,” I said, “that’s your old song.”

Then I realized it was being played for her and that she knew it. She laughed that divine soft laugh of hers.

“They always do that,” Irene said, “whenever I come here.” She sounded pleased but also shy. For in spite of her great success she’s never gotten over her shyness, It isn’t now—as it never was—a shyness that makes her awkward or gauche. She’s the most poised human being I know. Hers is a shyness of spirit. You sense it in her eyes, and in her laugh.

I was reminded that day of the first time I met Irene Dunne; long before she went into the movies. A friend of mine, one Elizabeth Russell of Louisville, Kentucky, very Southern, charming, rich and social, had said to me: “Elsa, would you very much mind meeting Irene Dunne? She’s a little friend of mine who is on the stage; but she is lovely really. . .”

We lunched, Elizabeth Russell, Irene and I, at the Ritz where the loveliest women in Ne w York always are to be found.

I thought, meeting Irene, “My dear, you are just a little girl who has come out as a young star. But you are going to be a great hit, you will go into the movies no doubt. And what will that do to you?” I didn’t like my conclusions. “She will lose her head,” I thought, “and her sense of values. It happens to all of them.”

I didn’t see Irene again for years, until 1933. She had, in the meantime, married Doctor Francis Griffin and come to Hollywood to make a musical version of “Present Arms,” which was called “Leather-necking.” A very bad picture it was, too!

Never will I forget how delighted I was I with Irene the night I went to her home to dine. For Irene and Frank have made a wonderful life for themselves. Neither their house nor their life pivots about any movie star routine. Away from the studios, Irene is one hundred per cent Mrs. Francis Griffin. With Frank she is as deliciously feminine as she is on the screen with Rex Harrison or William Powell. It is her good instinct to be a woman when she is with a man. Do I need add that men adore her?

Guests at the Griffins’ small parties are newspaper editors and people from Washington, all mentally invigorating. And Irene does not live like a guest in her home. She’s familiar with her kitchen. She’s familiar, too, with her garden and has won prizes in horticulture shows for her zinnias, the largest and most beautiful I have ever seen. Every week Irene teaches her daughter, Mary Francis, voice and the piano—after she has taken voice and piano lessons herself. Between her and her daughter there is a deep camaraderie. A good Catholic, she’s a familiar figure in her neighborhood church. Her thinking, too, is clear and direct. When she played Anna in “Anna and the King of Siam” I predicted, with enthusiasm, that she would be nominated for the Motion Picture Academy Award. She shook her head at me. “Elsa,” she pointed out indulgently, “you forget it is not a love story. And no girl can get an Oscar who isn’t taken into the fellow’s arms.” Right now she’s disturbed about the many magazine and newspaper stories which picture her as a grand lady. “I suffer,” she says, “from too many powder-puff burns.”

Which brings me to report that Irene is not only a grand lady, she’s also a fighter. Otherwise you would not know her. Back in 1930 when “Leathernecking” was a dismal failure and all musical pictures were in disfavor, the RKO studios, to whom Irene was under contract, wanted to get rid of her. They had so little confidence in her for anything but musicals that they did not even test her—although they tested practically every actress in town—for the coveted role of Sabra Cravat in “Cimarron.”

“I had to talk and talk,” Irene says “before I could convince them that since they were paying me a salary anyhow they had nothing to lose—except a few extra hundred feet of film—by letting me try for Sabra.”

Irene and Frank like to tell how she prepared to take that test. On the Sunday before she was to make it she implored Frank to play golf. But all day, from breakfast until dinner time, with only a brief pause for luncheon, he was her audience. This way and that she tried the lines until, by that intangible magic which a good actress creates, she finally captured the character of Sabra.

At the studio it was the same. When they brought her the clothes she was to wear for the test she frowned at the hat. “Sabra wouldn’t wear that hat,” she announced with that gentle firmness of hers which too many people do not plumb. “There is a sewing woman in the workroom who has just such a hat as Sabra would wear—so—on top of her head. I will borrow it from her.”

And it was with the sewing woman’s hat on top of her head—so—that she took the test that won her the role in “Cimarron” that rescued her from the discard, that launched her on her brilliant career.

However, hard as Irene will fight for her career and meticulously as she works when she is in production she does not put her career above all else. With her, first things come first . . .

Not long ago, when Frank Griffin had a heart attack, she bowed out of the picture for which she then was preparing. For two months she lived at the hospital with Frank. In fact from the moment he came home from the golf course after lunch to lie down because he felt ill she left his side only to go to church and pray.

At this time she and Frank were involved in negotiations for a Motel that they hoped, through their experience with the luxurious Beverly Hills Hotel in which they own an interest, would be the biggest and grandest and, by the same token, the most popular Motel in the world. But Irene let these negotiations go by the board to remain at Frank’s bedside.

“What is the use of millions without the husband you adore,” she said simply.

She has fight and spirit, depend upon that. She has humor, too. She laughs that delicious throaty laugh as she tells of a hectic Sunday in San Francisco when Harriet Parsons’s company of “I Remember Mama” was filming the elaborate 1910 sequence of this story. They were working in front of the famed Ferry Building in the horse-drawn vehicles of the period together with a few new-fangled horseless carriages. All San Francisco had turned out to watch the spectacle and it was no easy job to keep onlookers from swamping the camera, crew and actors. Two women finally did manage to get within conversing distance of Irene. One asked, “Is this going to be in Technicolor?” Before Irene could answer, however, the second woman said scathingly, “Don’t be a fool—they didn’t have Technicolor in 1910.”

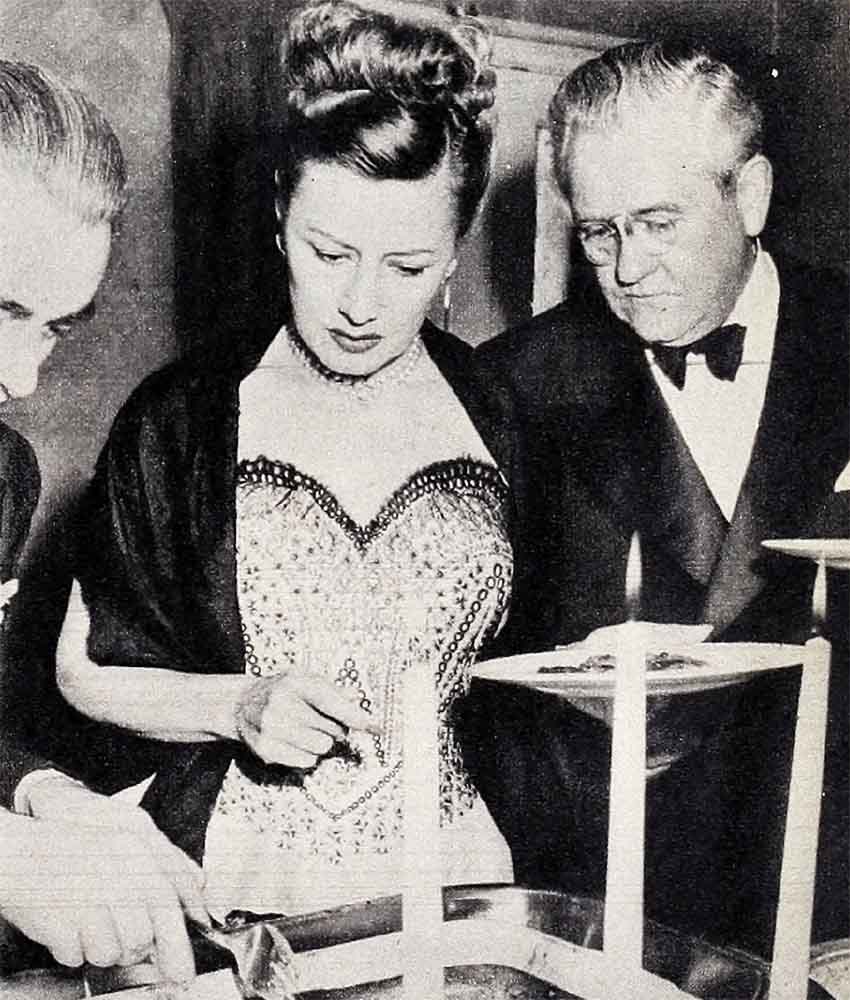

Above all there’s Irene’s loyalty. During the war she agreed to be a guest at the American Veterans’ Committee Ball at the Waldorf because I was one of the sponsors. There was much publicity that she would attend, of course, and all the GIs and sailors and their girls who were to be there were pretty excited at the idea of seeing Irene Dunne.

Somehow talk got about that the AVC was Communistic. So much talk in fact, that on the night of the ball, several of my guests who had promised to attend announced a change of heart.

“What about it, Elsa,” Frank Griffin asked, “is it Communistic? If so I would not wish to go or to have Irene appear.”

“Take my word,” I began, but I got no further.

“I will go with pleasure,” Irene said. And she was so gay and friendly and everyone adored her so that we finally had to form a phalanx to get her from the ballroom and upstairs to her suite.

It is her timidity that brings me to my most wonderful story. She will be a little annoyed with me for telling this, but I think she will laugh too.

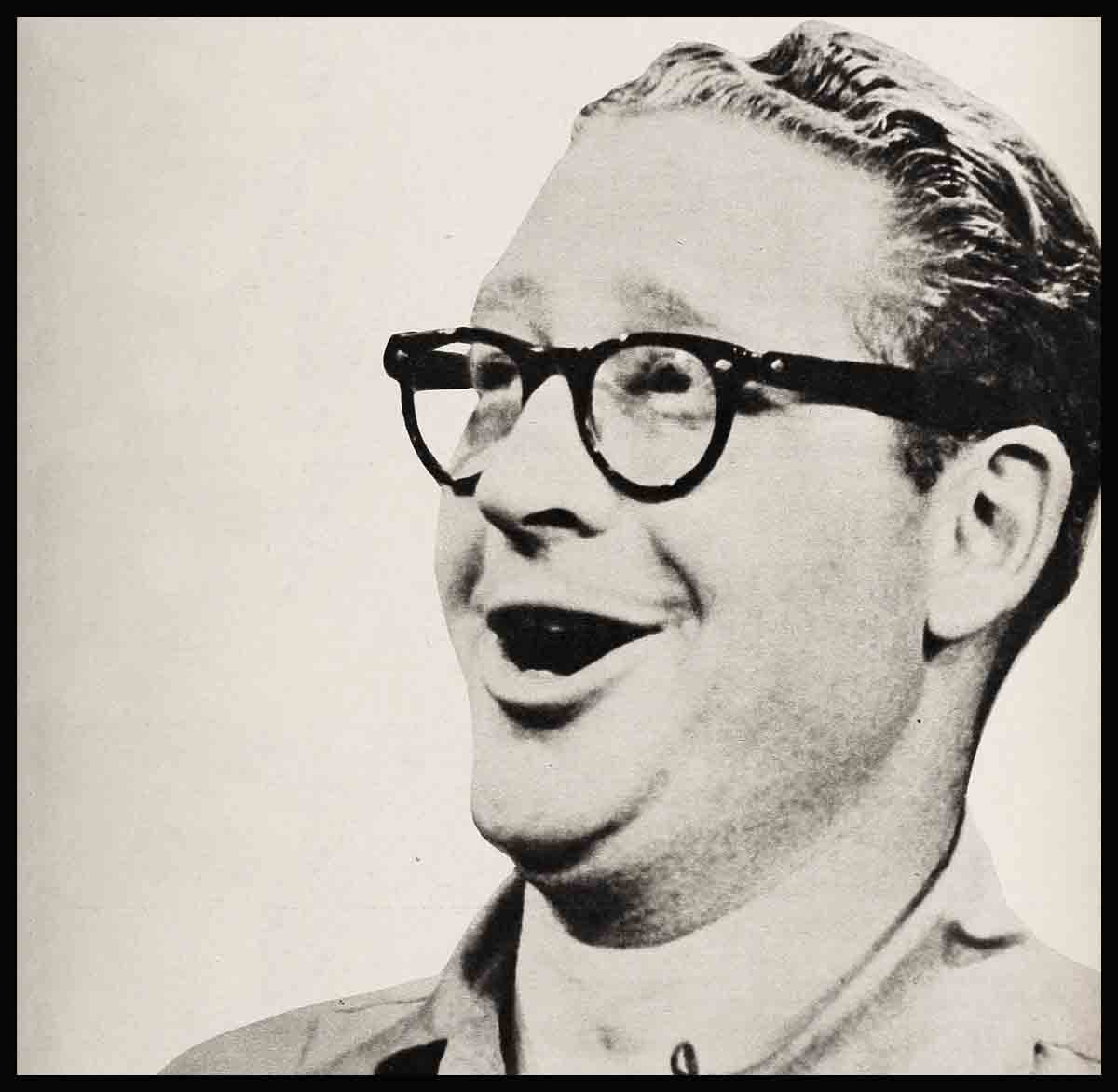

Several years ago, I was on the air with Paul Lukas. “Miss Maxwell,” he said when we were introduced before facing the mike, “I have a passionate interest in meeting you. You are one of Irene Dunne’s best friends. And I shouldn’t say it, perhaps, but I am madly in love with Irene Dunne even though I have never seen her off screen. She is my ideal.”

Reluctant as I was to squelch Paul’s Austrian romanticism, I reminded him that Irene was very happily married.

“I know, but I adore her,” he insisted.

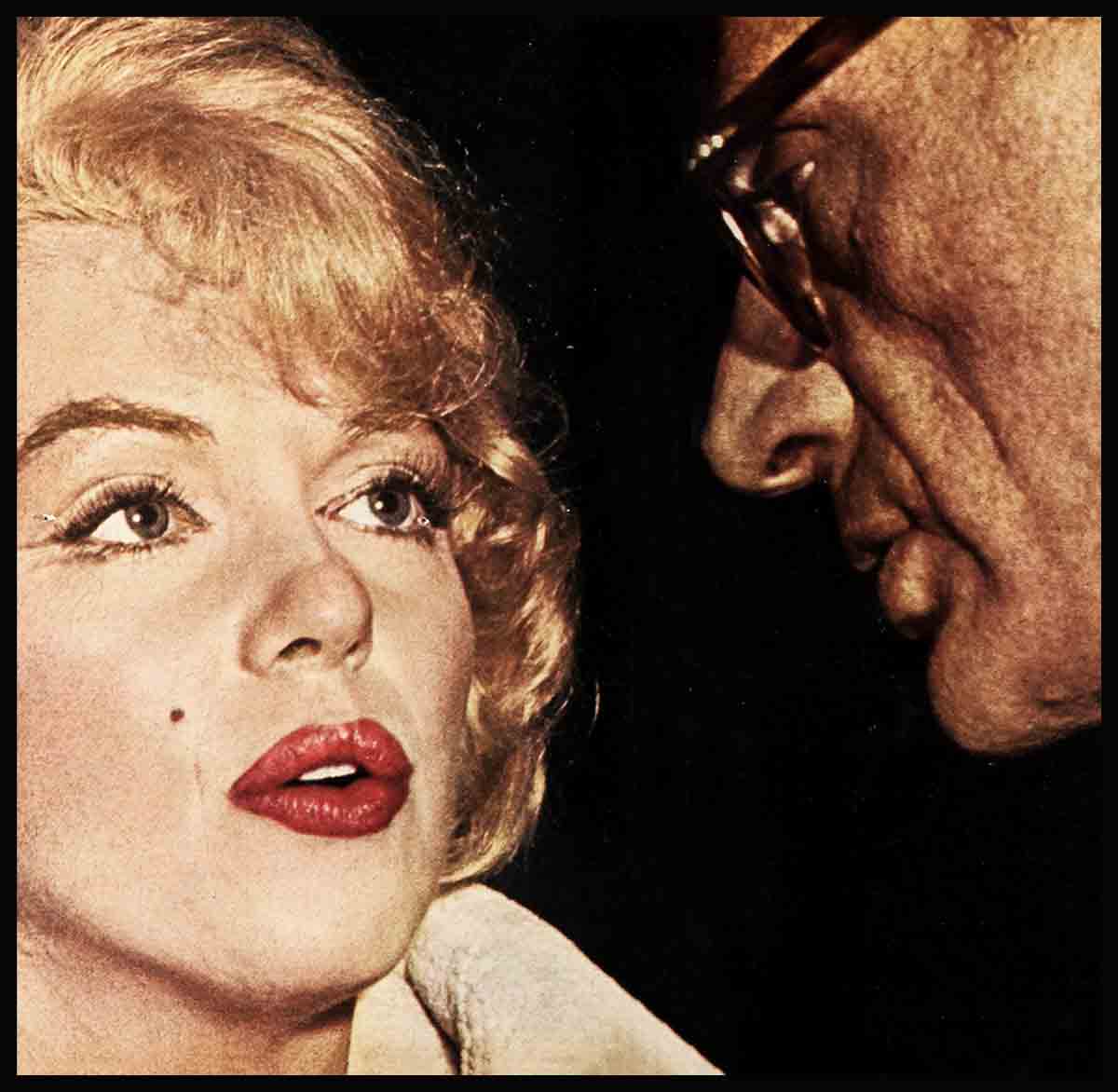

Not long after this Irene and Frank and another gentleman were my guests, when Paul opened on Broadway in “Watch on the Rhine.” Between the acts when the men were smoking I persuaded Irene to go backstage with me.

“Tell Mr. Lukas that Miss Maxwell and a friend would like to see him,” I said.

The door of Paul’s dressing room opened and we were ushered in.

“This is Miss Dunne,” I said, “who wants to tell you how good you are.”

Paul gave Irene no time to speak. ‘Miss Dunne,” he declared, “I adore you. You are my ideal!”

“Oh my!” said Irene, tugging at my sleeve. “That is very nice, Mr. Lukas . . . very nice. . . .” Her next tug at my sleeve could not be denied.

When we reached the corridor she turned to me, her eyes large. “Is the man mad?”

“Not at all!” I said. “He is a romantic Austrian.”

“Better not tell Frank,” she whispered.

But I made no promise. And later at supper I told Frank. He roared with laughter. For, just as I suspected, he thinks any man who does not adore Irene is remarkably undiscerning. And I agree.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1948

No Comments