Two Guys Named Mike

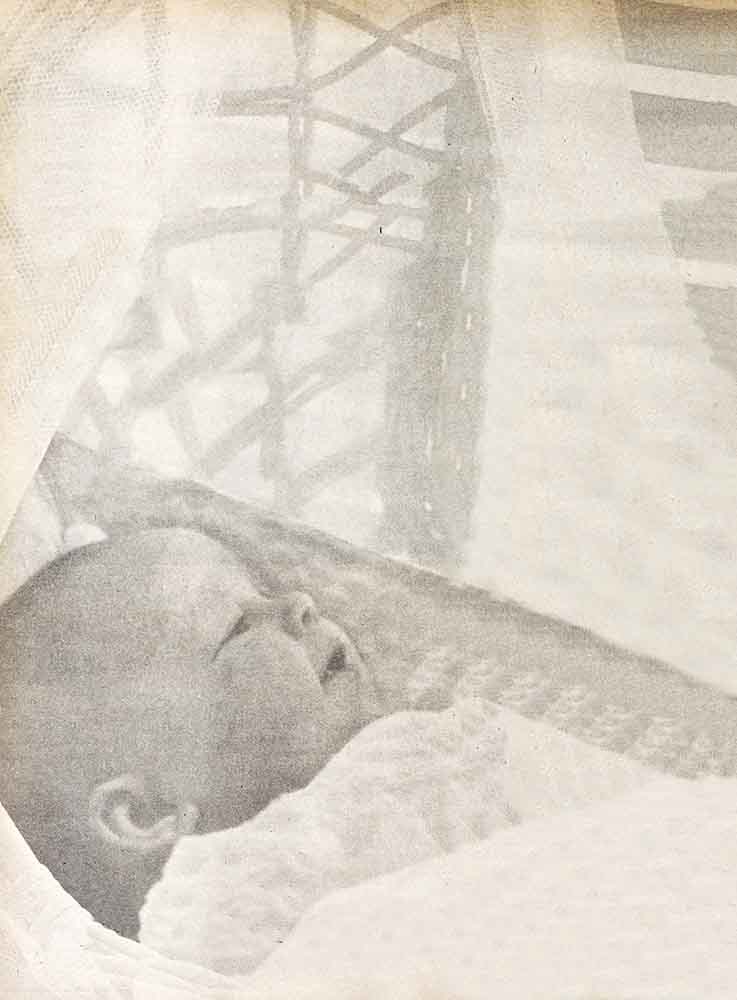

Michael Howard Wilding, aged five and one-half days, slept peacefully in his new nursery at home in a froth of yellow bassinet, his small left arm stretched above his head, his pink right fist clutched close to his chest. His head was small and perfectly formed.

“All babies born by Caesarian section have perfect heads,” said proud-to-bursting father Michael Wilding, conceding in the next breath that his and Elizabeth Taylor’s son’s was especially beautiful.

The baby’s thatch of jet black hair already had been coaxed into a soft curl on top of his head. “More hair than I have,” commented big Michael a little ruefully, “but less head.”

Small Michael’s ears were tiny shells, molded delicately, and flat against his head. His tiny nose turned up scandalously. His eyes were shut of course, but wide-set and sharply arched.

“Like his mother’s, thank God!” beamed his father. “And they’re dark blue like Elizabeth’s. I hope they stay that color.”

AUDIO BOOK

To have been invited into the nursery for a peek at the baby so soon after his arrival was a rare privilege which was obviously due to the eager pride of this obviously first-time father and the lenience of smiling nurse Mary Brice.

Photoplay had arranged months ago for the first interview with Michael Wilding after the baby’s birth. Though the studio had insisted that no reporters or photographers could see little Mike, or Liz till she was completely recovered, it had not counted on the fondly possessive pride of both these new parents.

“Look,” commanded Michael Wilding. No detail of his brand new son’s perfection could be ignored.

“Please notice,” he said, “that he is not wrinkled and he is not red.”

It was true. Becomingly pink cheeks glowed against the pillow. Tiny pink chin. But no red.

Still Michael could not bring himself to leave the baby’s side. He stood looking down at the child with a bewildered expression, as though not quite believing this miracle had happened.

“Look,” he said again, half-glancing at the nurse to see if he would be upbraided. Quickly he pulled back the cloud of yellow comforter to expose all of Michael Howard Wilding—all perfect.

The baby stirred a bit in his sleep, but didn’t wake.

“Isn’t he good natured?”

Mary Brice confirmed this. “He cries,” she said, “only when he is hungry.” But she added, “He will be hungry soon.”

At this point Elizabeth’s voice called weakly from the next room, “Michael.” And Michael leaped up and rushed off in the direction of the bedroom. He was back in a few seconds, saying “Wouldn’t you like to see Liz for a few minutes?” But the doctor’s orders?

“It’s all right. She says it’s all right.” He led the way to her bedroom.

Elizabeth was lying in the hospital bed, her eyes circled but shining, her natural high color emphasized by a soft fluff of pink bed jacket.

“Isn’t he beautiful?” was her first comment about little Michael.

Big Michael told a little joke, and Elizabeth tried to laugh, but couldn’t.

“It hurts to laugh,” Michael explained.

“It seems,” Elizabeth said, half apologetically, “as though it hurts to do almost everything . . . even breathe.”

Michael himself looked as though he could do with a little rest too. He was pale with fatigue—and expended emotion—and his eyes were bloodshot from lack of sleep. He looked as though he had had about ten babies himself.

“I never believed those stories before,” he said, “about fathers climbing the walls of the waiting room. But they’re true. Up until the very last minute I thought I was taking it all in stride.

“Elizabeth had X-rays on Monday—January 5, that was—and the pictures showed the baby was ready to be born. It was due, you know, on January 7. But right then and there our doctor, Konrad Aaberg, decided to take Elizabeth into the hospital on Tuesday night and deliver the baby by Caesarian section.”

Michael interrupted his story at this point to give special mention to Dr. Aaberg.

“Do you know Dr. Aaberg?” he asked. “He is the greatest doctor, the nicest, the gentlest guy. . . .”

Of course, all new parents feel that way about their obstetricians. But Dr. Aaberg was special, Michael insisted.

“Don’t you want to see the baby?” Michael asked Elizabeth.

Of course she wanted to see the baby, she smiled, but wasn’t he about to be fed?

“A couple of minutes won’t make any difference, so ask for him,” her husband urged her.

This time Elizabeth did laugh.

“He’s mad about him,” she said, unnecessarily.

“I’m stupid about him,” Michael retorted. And why not? After all, there had been a Michael in the Wilding family for hundreds of years, and he’d been the last until five . . . almost six . . . days ago.

Elizabeth asked the nurse to bring in the baby, “just for a few seconds.”

Michael agreed, after a moment, to allow Elizabeth to get some rest. He led the way back out into the big, informal living room from which the Wildings can see, when they have time again to look, a magnificent view of practically all of Southern California.

Michael settled himself on the broad circular sofa which curves around a massive fieldstone fireplace in one corner of the hospitable living room. He continued his recital of events of the night of the birth of little Michael.

“Well, anyhow, I drove Elizabeth down to Santa Monica Hospital at tenish Tuesday night. We were both very happy and excited . . . but not really nervous, if you know what I mean. Her parents met us there, and we all went up to the maternity ward to the two little rooms I had reserved for Liz’s confinement.

“Santa Monica Hospital is a small hospital, you know, and has no ‘living in’ facilities. Elizabeth wanted the baby near where she could see it whenever she wanted, so I took the extra little room next door. Outrageously extravagant, I suppose, but you don’t have a baby every day.”

“Thank Heaven,” he seemed to add under his breath as he sighed deeply before proceeding.

“Dr. Aaberg came in about ten-thirty. He was very confident and cheerful. A Caesarian, he assured me, took only eleven minutes. I would have word very soon whether we had a boy or a girl. Then he left to ‘wash up.’

“At about eleven two nurses came with a bed on wheels and took Elizabeth away.

“The Taylors and I sat back to wait it out. Eleven minutes, the doctor had said.

“After fifteen minutes I was climbing the walls, just like all the expectant fathers in the stories. After half an hour I was hanging from the chandelier.

“Elizabeth’s mother tried to reassure me.

It took some time, she said, to prepare a patient for major surgery.

“ ‘Major surgery!’ I heard the words which had been so matter-of-fact only yesterday with a sense of shock.

“Mr. Taylor tried to make little jokes. I should stop pulling my hair, he said, or I would be bald before my time. And he wondered if Santa Monica Hospital provided pressing service for new fathers. My clothes looked already as if I had slept in them.

But I couldn’t laugh. Thirty-five minutes, my watch said. Forty. Forty-five. The longest forty-five minutes I had ever endured in my life. What must it have been like for Elizabeth?

“And then a white-capped nurse knocked softly and came in. ‘If you will just come down the hail, Mr. Wilding,’ she said, ‘you can see your son!’ ”

The three of them—Elizabeth’s nearest and dearest—the three who loved her best, who were now to be four—walked, trembling, down the corridor, to the nursery window. It was midnight, so the curtains were drawn.

“Like an opening night,” Michael recalls, “but with no music . . . except our hearts knocking on our chests. It was an awful window . . . with a railing to hang onto. Designed, no doubt, for terrified fathers.

“A nurse in an antiseptic mask parted the curtains to expose a sea of little cots.

“The baby the nurse was holding up was mine. I looked at the little creature. I saw the mass of dark hair. One eye opened and looked at me. I gestured through the glass to the nurse to do something about the other eye . . . was something wrong? Right through the mask I could see her laughing at me.”

Then Dr. Aaberg, still in his surgical gown, came up behind them.

Mrs. Wilding, he told Michael, was back in her room. She had “stood the operation very well.” She was asking for her husband.

Elizabeth was quite conscious, and as yet in no pain. The “saddle block” anaesthesia had been chosen so that she could be in every way present at the birth of her child. She saw her son, as a matter of fact, five seconds after he was born.

Now back in the hospital bed in her room, she was radiant, her great eyes luminous with discovery and triumph.

“What did she say?”

“I don’t know what she said,” Michael replied to this question. “Maybe she didn’t say anything . . . she did it . . . it was how she did it. She asked for her baby and the baby was brought to her. She held him in her arms. I wish you could have seen her . . . she was like . . . like a flower.”

Michael’s voice was hoarse as he described that magic moment when the three of them were first together. He controlled it quickly.

“She is so sweet with the baby. The only times she feels really well—so far—is when she is with the baby. The pain goes—somehow.

“Dr. Aaberg says she is a natural mother.”

And Michael is a . . . well . . . a classic father. He agreed to leave the hospital that night only because Dr. Aaberg insisted. Elizabeth must rest, and so should he. And besides, it was the rule. He walked out into the Street and saw a newspaper with a banner line reading, “Liz Taylor Has Baby Son.”

He drove home slowly with no idea in retrospect how he negotiated the hairpin turns on the long grade to their mountain top. He threw his clothes on a chair, himself on the bed—the big, low bed which seemed so ridiculously oversized for one weary man.

He slept, fitfully, but hopped up with the first sound of activity in the house next morning. The housekeeper must know the news, and Elizabeth’s secretary. A paper hanger came to put the finishing touches to the nursery and Michael retold the whole story to him.

“The baby really weighed seven pounds, five ounces,” he bragged, “but we get credit for only seven-three. He lost two ounces in that business they do to new babies to make it easier for them to breathe.”

“Seven-three is very good,” the paper hanger, a father himself, assured him. Mr. Wilding, no doubt, would be handing out cigars.

Cigars? Michael had no cigars. He hadn’t known about cigars. It was an American custom.

The paper hanger looked disappointed. It must be an important American custom, Michael realized. Then he remembered something, and dashing back to the bedroom, dug through his bureau drawers until he found what he wanted: a cigar Geary Steffen had given him when his baby had been born six weeks before. He gave it to the paper hanger, who looked relieved, and Michael vowed to buy more the first minute he got into town.

He never did buy the cigars. Elizabeth was feeling miserable when he arrived at the hospital, and Michael stayed by her bedside for ten hours that day, and the next. And the next.

On Sunday morning, the fifth day, they brought her and the baby home. . . .

“It was soonish, but she longed to be home. We brought along Mrs. MacKenzie, the nurse who had looked after her in the hospital; you need some one to wash you, you know. And we rented a hospital bed—easier to get in and out of; to walk about. They made her walk about, you know, even that first day. And she was in such pain.”

But as Michael had said, the pain disappeared when she was with the baby. For now truly she was—as in her new movie, “The Girl Who Had Everything.” Future movie assignments, like “all the Brothers Were Valiant,” could wait—all Elizabeth had time for now was her two guys named Mike.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1953

AUDIO BOOK

No Comments